Introduction

Altered sensation in the head and neck can be associated with a broad array of local, regional, and systemic etiologies. Though there are multiple cranial and cervical peripheral nerves supplying the craniofacial region, neurosensory disturbance of the inferior alveolar nerve (IAN), its terminal branches, and the lingual nerve are most likely to present in dental practice. Though iatrogenic trauma is often suspected in the patient presenting with altered facial sensation in the context of recent intraoral procedures, the following six cases exemplify a variety of other underlying pathologic conditions presenting with altered facial sensation.

Case 1

A 60-year-old male was referred for a 6-month history of reduced sensation in the anterior mandible with associated burning and tingling of the left tongue following implant placement. The patient endorsed transient left sided facial swelling refractory to antibiotics with intermittent pain radiating to the temporal region. The patient had 5 to 6 kg of weight loss over a 6-month period. On exam, there was bilateral V3 paraesthesia with palpable cervical and supraclavicular nodes. Intraorally, the soft tissue of the anterior mandible was erythematous and boggy to palpation with a mobile implant. Cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) revealed bony destruction around the mobile implants. (Fig. 1) An incisional biopsy of the bone was completed with a differential diagnosis of infection versus malignancy. The biopsy confirmed adenocarcinoma requiring further oncologic workup and management.

Fig. 1

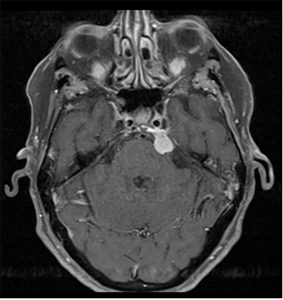

Case 2

A 78-year-old female presented with a 1-month history of intermittent hypoesthesia of the left upper and lower lips with no pain, swelling or prior facial surgery. On exam, V1 was intact bilaterally with reduced sensation (80%) in the left V2/3 regions. The remainder of cranial nerves II-XII were grossly normal on exam. There were no signs of infection, oral mucosal lesion or facial masses. No focal anomalies were detected on panoramic imaging. Head and neck computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies were obtained as a result of the clinical findings. (Fig. 2) These demonstrated an extra axial lesion near the junction between the left tentorium and the cisternal face of the petrous apex. This lesion in the left prepontine cistern was consistent with a meningioma or schwannoma and a neurosurgical consultation was initiated.

Fig. 2

Case 3

A 33-year-old female was referred for persistent left tongue anaesthesia 1 week after extraction of tooth 38. On exam, an ulcer was present lingual to site 38. Neurosensory testing revealed anaesthesia of the left tongue with anaesthesia including no perception to temperature, nociception, 2-point discrimination or directional sensation. At 2 months, site 38 was healing as expected with no improvement in the aforementioned neurosensory tests. A panoramic radiograph was taken. (Fig. 3) Microsurgical exploration and repair with nerve allograft and a connector was completed. Surgical pathology revealed a left lingual nerve neuroma. The patient has recovered and now has improved sensation, but with hypoesthesia in various areas of the left tongue in addition to nociception and cold sensation post-operatively.

Fig. 3

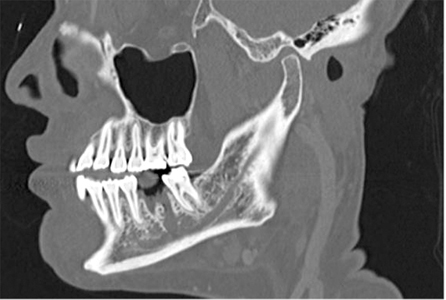

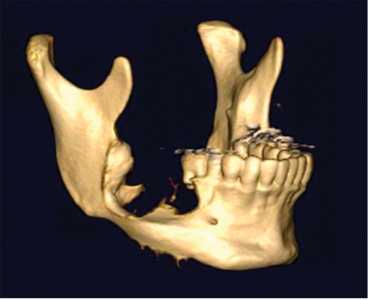

Case 4

A 52-year-old female was referred to our centre for right IAN anaesthesia after extraction and curettage at site 46. Panoramic and CT imaging was acquired. (Fig. 4) Based on clinical history, there was concern for potential nerve transection. Exploration of the right IAN via mandibular osteotomies with right sural nerve graft harvest and inferior alveolar nerve reconstruction was completed. The patient is currently being followed closely for neurosensory recovery.

Fig. 4

Case 5

A 23-year-old male was referred for a cystic appearing lesion in the right mandible found incidentally on periapical imaging. The patient reported a 1-year history of a right mandibular expansion with no pain, paraesthesia, or previous trauma. On exam, a 3cm exophytic mass with erythroleukoplakic change and ulceration was noted. Panoramic and CT imaging was obtained demonstrating an expansile lytic lesion in the posterior right mandible. (Figs. 5 & 6) An incisional biopsy was performed which revealed findings consistent with a conventional ameloblastoma. A bilateral CT angiography of the lower extremities was obtained for surgical planning. Resection of the right hemi mandible was completed with a fibular free flap reconstruction. The patient has a resultant loss of right IAN sensation due to the nature of the pathology and required resection margins.

Fig. 5

Fig. 6A

Fig. 6B

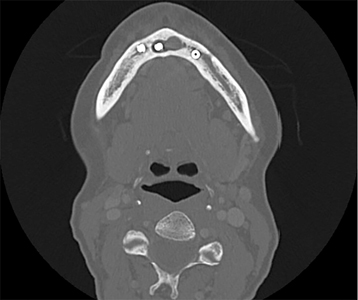

Case 6

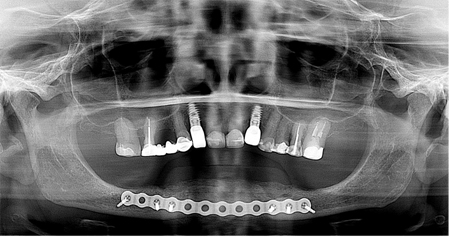

A 55-year-old female with 25 pack year history of smoking was referred for persistent pain, swelling and loss of implant placed at the site of 31 in the setting of 4 mandibular implants placed with the goal of working towards a fixed prosthesis. Initial exam revealed swelling along the inferior border of the mandible and hypoesthesia to the lower lip bilaterally. Radiographic and clinical findings supported the diagnosis of a chronic sclerosing osteomyelitis of the mandible. (Fig. 7) Definitive management consisted of removal of all implants, anterior iliac crest bone grafting for mandibular reconstruction and long-term oral antibiotics. (Fig. 8)

Fig. 7

Fig. 8

Discussion

In the approach to the patient presenting with a chief complaint of altered sensation, a thorough history is the foundation to formulating a differential diagnosis. In the setting of postoperative neurosensory disturbance following a dental or dentoalveolar procedure, the patient’s subjective history is often concise and focused to an acute onset altered sensation in the immediate post operative period. Certainly, witnessed or unwitnessed causes of iatrogenic trauma to the lingual and IANs during such procedures are numerous, and may include local anesthetic injections, exodontia, root canal over-instrumentation or material extrusion, dental implant placement, osteotomies, or ablative procedures1. A history of recent dental or dentoalveolar procedures in the setting of new onset neurosensory disturbance does not, however, preclude non-iatrogenic causes of altered sensation, and a high index of suspicion must be maintained for other possible pathologic processes. The ‘OPQRST’ mnemonic aids in formulating concise inquiries into the history of presenting illness to document a focused and meaningful history. (Fig. 9) Of note, the presence of pain, and the perceived impact on quality of life are important to describe2. Beyond a focused dental history, review of the present state of health and past medical and oncologic history, medication history, surgical history, social history including recent travel, and family history may reveal pertinent positives and negatives to guide a context-appropriate differential and subsequent investigations.

Fig. 9

Clinical examination of the head and neck should screen for surgical scars, radiation fibrosis, cutaneous lesions, fistulae, masses, and lymphadenopathy. Intraorally, screen for surgical scars, lesions, masses, areas of exposed bone, marked dental mobility or migration, vestibular fluctuance, or cortical expansion. Closely examine any areas of recent intraoral procedures specific to the presenting complaint in question. Neurosensory testing of the affected dermatome can then be performed to objectively evaluate the dermatome(s) in question, using the contralateral dermatome as a control if unaffected. In dental practice, this often involves testing trigeminal distributions in the lower lip, chin, and labial mucosa, or tongue, floor of mouth, and lingual gingiva. Neurosensory testing should allow appraisal of contact detection, pressure, temperature, proprioceptive, and pain pathways, mapping of the boundaries of the deficit, and quantifying severity3. Clinical terminology such as paresthesia, hypoesthesia, anesthesia, dysesthesia, allodynia, hyperalgesia, and hyperpathia allows effective communication among colleagues and appropriate triage4.

Imaging may include conventional 2-dimensional intra- and extra-oral radiography, orthopantomography, CBCT, CT, MRI, ultrasonography, or nuclear imaging5,6. Imaging may reveal the presence of foreign bodies, intra-osseous pathology, cortical discontinuity, intracranial pathology, peripheral nerve lesions or continuity defects, or metabolic activity suggestive of inflammation or neoplasia. In the setting of suspected systemic pathology such as demyelinating polyneuropathies, autoimmune conditions, metabolic syndromes, or endocrinopathies associated with altered sensation, additional laboratory and serologic tests are pursued. Management of altered sensation of the face are beyond the scope of this article, however an accurate diagnosis and management of underlying pathologic processes are paramount.

Conclusion

Though iatrogenic trauma is likely the most feared presentation of neurosensory disturbance in dental practice, it is important to consider the presence of recent intraoral procedures as a possible ‘diagnostic red herring’. Other pathology to consider in the differential of altered sensation of the V2/V3 distribution which may be prompted by history and clinical examination include but are not limited to osteomyelitis, medication-related osteonecrosis, osteoradionecrosis, odontogenic tumors, salivary gland malignancy, squamous cell carcinoma, mesenchymal tumors, viral infections, intracranial lesions, peripheral nerve lesions, autoimmune conditions, and metabolic syndromes. The cases presented in this article highlight a few of the many possible pathologies that may underlie the patient presenting with altered facial sensation in the trigeminal nerve distribution.

Oral Health welcomes this original article.

† Corresponding Author: Dr. Karl Cuddy Assistant Professor, Director of Education and Maxillofacial Trauma, Graduate Training Program in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, University of Toronto. 124 Edward Street Room 143, M5G 1G6, Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Email: karl.cuddy@utoronto.ca

Disclosing information: None to disclose.

References

- Tay AB, Zuniga JR. Clinical characteristics of trigeminal nerve injury referrals to a university centre. International journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery. 2007 Oct 1;36(10):922-7.

- Zuniga JR, Yates DM, Phillips CL. The presence of neuropathic pain predicts postoperative neuropathic pain following trigeminal nerve repair. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2014 Dec 1;72(12):2422-7.

- Meyer RA, Bagheri SC. Clinical evaluation of peripheral trigeminal nerve injuries. Atlas of the Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Clinics of North America. 2011 Mar 1;19(1):15-33.

- Loeser JD, Treede RD. The Kyoto protocol of IASP basic pain Terminology. Pain. 2008 Jul 31;137(3):473-7.

- Miloro M, Kolokythas A. Inferior alveolar and lingual nerve imaging. Atlas of the Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Clinics of North America. 2011 Mar 1;19(1):35-46.

- Nazerani, T., Kalmar, P., Aigner, R. M. Emerging Role of Nuclear Medicine in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. In: Sridharan, G., editor. Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. DOI: 10.5772/intechopen.92278

About the Authors

Dr. Andrew Lombardi is an Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery intern, University of Toronto.

Dr. Andrew Lombardi is an Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery intern, University of Toronto.

Dr. Christopher Bernard is a senior Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery resident, University of Toronto.

Dr. Christopher Bernard is a senior Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery resident, University of Toronto.

Dr. Karl Cuddy is an Assistant Professor and Director of Education and Maxillofacial Trauma for the Graduate Training Program in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery at the Faculty of Dentistry, University of Toronto.

Dr. Karl Cuddy is an Assistant Professor and Director of Education and Maxillofacial Trauma for the Graduate Training Program in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery at the Faculty of Dentistry, University of Toronto.