Introduction

Fluorescence visualization (FV) as an adjunctive tool for general dental practitioners in routine soft tissue oral examinations was first introduced as the VELscope™ in 2006 by LED Dental. Since that time there has been a significant amount of clinical research evaluating its use in both routine oral examination and surgery. This clinical research has informed the dental community on many aspects of FV usage in dentistry. This article will briefly discuss the state of the clinical research regarding FV and highlight two recent papers to see what insights they provide on its utility for routine screening and surgical applications.

FV in Routine Oral Examinations

In clinically evaluating any medical device, it is critical to understand its intended use. The Indications for Use statement that always accompanies the device is an excellent place to find this. It is one of the most important elements that regulatory bodies such as Health Canada and the FDA pay attention to when clearing and approving devices for sale. Figure 1 provides the Indications for Use for the VELscope Vx system.

FIGURE 1. VELscope Vx Indications for Use.

Notice that the VELscope Vx:

• Is an adjunct to the comprehensive oral exam (COE) and therefore to be used together with it and not to replace it.

• Can enhance visualization of all abnormalities, not just dysplasia and oral cancer (which are provided as examples of serious abnormalities).

• Is not intended to “diagnose” and is not a replacement for biopsy.

Notwithstanding these considerations many studies have been conducted that:

• Treat the FV exam as an alternative to COE and compare the effectiveness, one against the other.

• Treat the FV exam as a stand-alone diagnostic procedure and compare the FV “results” with biopsy results.

• Treat the FV exam as if it is intended to help detect ONLY dysplasia and cancer and label detection of other abnormalities as “false positives”.

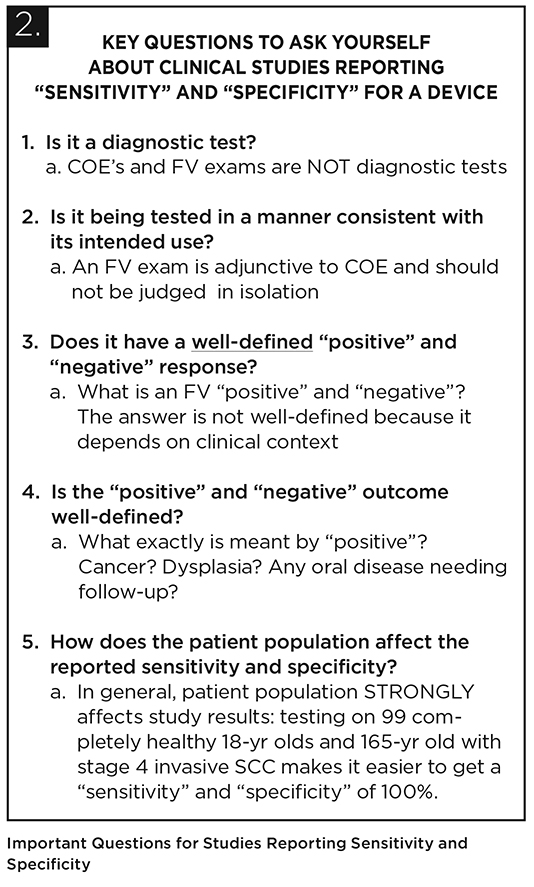

Rather than contribute to our understanding of the appropriate role of FV in dentistry, studies designed in this way can be confusing and leave a false impression. Many papers present “sensitivity” and “specificity” values and attempt to apply these terms to a measurement of the performance of the FV and/or the COE exam. Typically, these are terms that measure the performance of a diagnostic test, and this applies neither to the COE nor the FV exam. Using them in other contexts can be appropriate but requires careful thought and explicit definition of terms. Figure 2 highlights some of the questions readers should ask themselves when trying to make sense of sensitivity and specificity.

FIGURE 2. Important Questions for Studies Reporting Sensitivity and Specificity

Notwithstanding the above discussion, many investigators have been mindful of the appropriate intended use and designed studies with the goal of developing better strategies for incorporating fluorescence visualization into robust clinical decision making in routine oral examinations.1,2 A particularly interesting study was conducted by a group in Brisbane, Australia3 to evaluate the performance of a combined decision making protocol based on both COE and a VELscope examination compared with the performance of using either COE or VELscope in isolation. The performance was measured by comparing the referral decisions made by a general dental practitioner (GDP) with the independent decision of an oral medicine specialist (OMS) who had extensive experience using the VELscope. The OMS decision was considered to be the “soft gold standard” and, as such, a “true positive” or “true negative”; the GDP decision to refer to an OMS was considered as a “test positive” or “test negative” and was compared against the OMS decision for the calculation of sensitivity and specificity reported in the results. For example, if the GDP using one of the above three methods were to make a decision to refer 100% of the patients that the OMS decided needed referral, then that method was deemed to have a “sensitivity” of 100%.

The basis of the decision to refer using the three methods was as follows:

1. COE alone

a. Non-Inhomogeneous leukoplakia considered suspicious for dysplasia/cancer and labelled as a “referral”.

2. VELscope alone

a. Lesions displaying loss of autofluorescence (LAF) and demonstrating no or partial blanching considered suspicious for dysplasia/cancer and labelled as a “referral”.

3. Combined Decision Making Protocol

See the Figure 3 for a summary of the protocol to understand how this protocol generated “referrals”.

FIGURE 3. Summary of the Combined Decision Making Protocol.

305 patients presenting for general dental treatment were screened by the general dental practitioner for oral lesions, first by the comprehensive oral exam, then by a VELscope examination. A review was scheduled in 14 days as appropriate and in accordance with the protocol in Figure 3. In total 222 lesions were discovered in 146 patients. Twenty-five of the lesions in total were recommended to be referred based on the OMS decision.

305 patients presenting for general dental treatment were screened by the general dental practitioner for oral lesions, first by the comprehensive oral exam, then by a VELscope examination. A review was scheduled in 14 days as appropriate and in accordance with the protocol in Figure 3. In total 222 lesions were discovered in 146 patients. Twenty-five of the lesions in total were recommended to be referred based on the OMS decision.

The sensitivity and specificity for the three methods are shown in the table below:

Note that sensitivity and specificity of using the VELscope and the COE together using considerations from both leads to a higher sensitivity and specificity than either one alone. This result fully supports that an FV exam adds value when used adjunctively to COE. It should be remarked that the decision in the study to refer based on “VELscope alone” is by design, not a nuanced one, and deciding to refer every non-blanching lesion to a specialist will of course lead to over-referrals. However, in the context of this study, analyzing the results in this manner serves to illustrate the importance of using clinical judgment to combine considerations from both the COE and VELscope exam and use follow-up exams as appropriate.

The study is relevant to the general dental practitioner because it outlines in many respects the appropriate way to integrate FV into practical decision making with patients:

• Performing a COE and making a decision to refer lesions definitely suspicious for dysplasia or cancer.

• Following the COE with an FV exam and utilizing blanching technique to gather more information about the role of inflammation in the lesion.

• Re-examining FV-detected lesions under white light and use clinical judgment to try to find reason for LAF on clinical grounds.

• Having patients return for a review in 14 days to check lesion resolution; persistent lesions with no identified benign cause are referred.

In general, there are some facets of the combined decision making protocol that one could argue should be refined for everyday use:

• Inflammatory lesions may need treatment for resolution and so it would seem appropriate to recommend using clinical judgment to try to determine the cause of a lesion and take appropriate steps to resolve if possible (e.g. anti-fungal medication for a fungal infection or addressing possible cause of lichenoid reaction, e.g. medication, restorative materials, or chronic trauma caused by tooth) before having a patient back to check for resolution of the lesion. Some benign lesions may not spontaneously resolve.

• It is possible that a lesion may be discovered under an FV exam that was not noticed in the COE but may warrant immediate referral to rule out dysplasia.

• LAF although well-defined and convenient for a quantitative study is not necessarily an appropriate way to describe a fluorescence response that indicates an abnormality. Not only because general inflammation will cause a LAF but also because there are many examples of perfectly normal tissue in the oral cavity that display LAF – tonsillar and lymphoid tissue, the well vascularized anterior tonsillar pillars, to name but a few. Also, sometimes an abnormality can present as an increase in fluorescence. A better working definition to use is an abnormal pattern of fluorescence, which is atypical for the type of tissue being visualized. In this manner an increase in fluorescence that is unusual, unexplained or out-of-place is also naturally viewed as an “abnormality” also possibly requiring follow-up.

The authors of this paper state:

This is an excellent statement of the aim of an oral mucosal examination but which “oral mucosal abnormalities” are appropriate for detection and referral as appropriate? Surely, the objective of an oral mucosal exam should be the detection of all lesions requiring some sort of follow-up or intervention by the dentist or specialist to improve the health or quality of life of the patient. In addition to dysplastic and cancerous lesions this would then also be inclusive of “benign” lesions such as lichenoid reactions or fungal, viral or bacterial infections or other types of conditions (e.g. denture sore spots) where identification and treatment is beneficial to the patient. The paper explicitly mentions dentures sore spots: “A common finding in this study was the presence of areas of LAF under dentures in clinically normal tissue displaying chronic inflammation.” They remark that other investigators4 biopsied all lesions such as this that did not resolve. This is the typical circumstance in which an abnormality such as a denture spot can be classified in a study as a “false positive” and thus, cast in a negative light although its detection and resolution is beneficial to the patient (from a comfort perspective and also because of the possible negative consequences of long-term chronic inflammation).

This is possibly the first study incorporating FV to try to quantitatively analyze the utility of using diascopic pressure to blanch tissue as an aid to clinical decision making. The theory behind using diascopic pressure is that inflammation will blanch (the redness will dissipate) when diascopic pressure is applied to tissue because the blood in the vessels is mobile and will get pushed out of the way. Under fluorescence, blanching tends to show a dramatic visual change from a pronounced loss of fluorescence due to blood absorption to normal bright fluorescence after the blood is pushed out of the way. Figure 4 summarizes some common types of lesions and their response to diascopic pressure.

FIGURE 4. Diagram outlining blanching response of different types of lesions

Dysplastic and cancerous lesions can demonstrate a loss of fluorescence that is unrelated to blood absorption (changes in collagen and abnormal metabolism in epithelium) which will not blanch. However, as can be seen, other types of lesions also contain non-mobile sources of LAF and will also not blanch. Figure 5 shows an example of an inflammatory lesion (denture sore spot) which completely blanches and Figure 6 an ecchymosis, which does not. The ecchymosis resolved completely within two weeks.

FIGURE 5. Complete blanching of inflammatory lesion. Photos courtesy of Benjamin Dental Group.

FIGURE 6. Lesion does not blanch because of the presence of extravasated blood. Photos courtesy of Benjamin Dental Group.

In the study, the investigators tracked the various categories of blanching and noted that the highest rate of healing of the lesion at the 14-day review was interestingly the lesions that didn’t blanch at all. They note that this is most likely with the result of “the presence of extravasated haemoglobin in acute traumatic events which are a frequent occurrence in the oral environment.” It is clear that clinical judgment and the appropriate use of a follow-up exam in two to three weeks to check for resolution should be used.

A very important point to understand is that dysplastic and cancerous lesions can often contain an inflammatory component which can lead to “partial” blanching (Fig. 7). The inflammation inside white circle blanches under diascopic pressure (photo courtesy of the University of Washington Oral Medicine Program).

FIGURE 7. Cancerous lesion showing LAF due to cancer but also due to inflammation (white circle).

In the study, lesions which partially blanched were associated with the highest rate of referrals – this is certainly an interesting observation and worthy of note by general practitioners using fluorescence visualization in their practice.

FV as a Surgical Margin Tool

The fact that FV, and in particular VELscope, can be used by surgeons to help delineate the surgical margin around cancerous lesions is nothing new. The regulatory approval (2007) of this indication was based on a paper5 by Catherine Poh and colleagues, reporting the success of this technique on a limited number of patients.

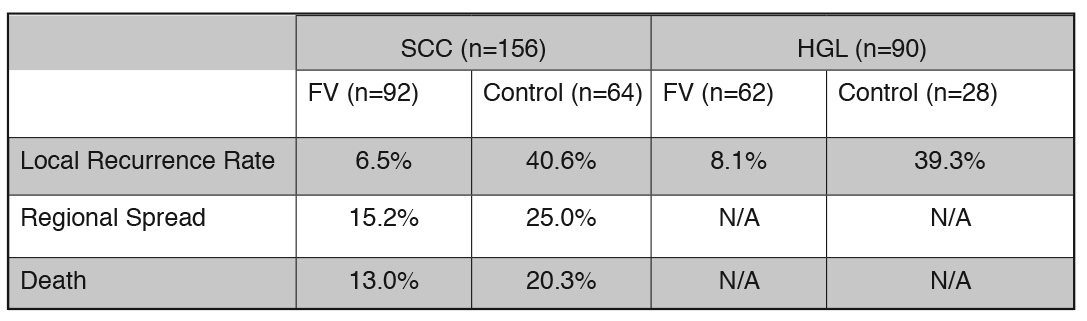

Poh and colleagues recently published a paper6 that built on their earlier work by comparing a group of patients treated by surgical excision under FV guidance to a group who underwent conventional surgery. They performed a comprehensive retrospective analysis on 246 patients that had been treated for squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) or high-grade lesions (HGL – severe dysplasia and carcinoma-in-situ) at the BC Cancer Agency between 2004 and 2009. One hundred and fifty-four patients underwent FV-guided surgery while 92 underwent conventional surgery. Of the 246 patients, 156 had localized SCC of less than 4 cm and 90 were treated for an HGL. Local recurrence rates, regional failure rates (spread of the disease to a cervical lymph node) and death rates were determined at a minimum of three years post-surgery. The results are summarized in Figure 8.

The statistically significant reduction in local recurrence in the FV groups for both SCC and HGL patients is striking and is an impressive demonstration of the utility of fluorescence to improve the surgeon’s ability to remove diseased tissue around a cancerous or dysplastic lesion. Note also that in all patients, the surgical margins were checked and if severe dysplasia or cancer was detected at the margin, additional tissue was excised.

The investigators also discuss the deep margin (at the surgical bed) where the use of fluorescence is problematic, primarily because of intraoperative bleeding, which would totally dominate the fluorescence response. They remark that despite having no additional aids like fluorescence visualization, the deep margin did not play a significant role in their results because of the extensive experience of the surgeons who conducted the surgeries. The deep margins were checked and no evidence of SCC was observed for the study patients.

It can also be seen from the above table that rates of regional spread and death in SCC patients were also noticeably lower in the FV group, although the authors remark that the rate differences did not reach statistical significance.

Despite the impressive nature of these retrospective findings, the authors recognize that to effect widespread change in surgical practices, a randomized prospective clinical study is necessary. To that end, a multi-centre phase three clinical trial has been underway since 2010 and has already completed enrolling and treating 400 patients; 200 in a control group using traditional surgical methods and 200 in a group using FV guided surgery. This so-called COOLS (“Canadian Optically guided approach for Oral Lesions Surgical”) Trial6 involves multiple sites across Canada and includes five years of follow-up on treated patients. Results of this study are expected later this year.

Conclusion

In conclusion, it is clear that the clinical research associated with the use of FV as an adjunctive tool for routine oral mucosal examination and surgery continues to evolve. Moreover, investigators are becoming increasingly sophisticated in their understanding of the technology and its appropriate role while conducting more meaningful studies to better identify the benefits that fluorescence can bring to clinical decision making. In particular, with recent published data and the results of a new study to be released this year, FV seems poised to take on a larger role in the surgical excision of high-grade and cancerous lesions. OH

Oral Health welcomes this original article.

References:

1. Truelove EL, Dean D, Maltby S, Griffith M, Huggins K, Griffith M, Taylor S. Narrow band (light) imaging of oral mucosa in routine dental patients. Part I: Assessment of value in detection of mucosal changes. Gen Dent 2011; 59(4): 282-289.

2. Laronde DM, Williams PM, Hislop TG, Poh C, Ng S, Bajdik C, Zhang L, MacAulay C, Rosin MP. Influence of fluorescence on screening decisions for oral mucosal lesions in community dental practices. J Oral Pathol Med. 2014 Jan;43(1):7-13.

3. Bhatia N, Matias MA, Farah CS. Assessment of a decision making protocol to improve the efficacy of VELscope™ in general dental practice: a prospective evaluation. Oral Oncol. 2014 Oct;50(10):1012-9.

4. McNamara KK, Martin BD, Evans EW, Kalmar JR. The role of direct visual fluorescent examination (VELscope) in routine screening for potentially malignant oral mucosal lesion. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2012 Nov;114(5):636-43.

5. Poh CF, Zhang L, Anderson DW, Durham JS, Williams PM, Priddy RW, Berean KW, Ng S, Tseng OL, MacAulay C, Rosin MP. Fluorescence visualization detection of field alterations in tumor margins of oral cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res 2006;12(22):6716-6722.

6. Poh CF, Durham JS, Brasher PM, Anderson DW, Berean KW, MacAulay CE, Lee JJ, Rosin MP. Canadian Optically-guided approach for Oral Lesions Surgical (COOLS) trial: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. BMC Cancer. 2011 Oct 25;11:462.

Follow the Oral Health Group on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and LinkedIn for the latest updates on news, clinical articles, practice management and more!