Odontomas represent the most common odontogenic tumor, with a prevalence that exceeds that of all other odontogenic tumors combined.1 The designation of odontoma as a tumor is misleading; the entity is in fact a hamartoma with limited growth potential. Growth of the lesion ceases following maturation of the lesional tissues.2,3 Odontomas arise from both odontogenic epithelium and mesenchyme, leading to a lesion that is comprised of mature enamel, dentin, cementum and pulpal tissues with a distinct physical appearance that is different from normal tooth structure. Odontomas are subclassified as compound or complex. Compound odontomas are comprised of multiple incompletely developed tooth-like structures. Complex odontomas consist of a single mass of mineralized odontogenic tissues. There exists a spectrum between these classifications in which the hamartoma presents as a mixed complex-compound growth. The most common clinical finding is lack of timely eruption of a permanent tooth, due to obstruction from the lesion. Painless expansion of the alveolus may also be present. Radiographically, the lesions are located in tooth-bearing areas. Maxillary lesions are commonly located in the anterior and canine regions, with mandibular lesions showing a predilection for the molar region. Differential diagnosis includes supernumerary teeth and ossifying fibroma.4 This paper will present a case of a complex-compound odontoma in a paediatric patient.

CASE HISTORY:

A 9 year old male was referred for evaluation and surgical management of a lesion of the anterior maxilla. The presenting chief complaints included failure of eruption of teeth # 21 and 22, and a bump on the gum in this region. The patient was otherwise in good health, with no reported medical comorbidities. There was a history of gastrointestinal surgery at 2 years of age, with no reported complications.

Clinical examination revealed retention of primary teeth #61 and 62, and eruption of permanent teeth #11 and 12. There was marked dental crowding. Additionally, there was evident expansion of the alveolar process in the 21/22 area. (Fig. 1)

Fig. 1

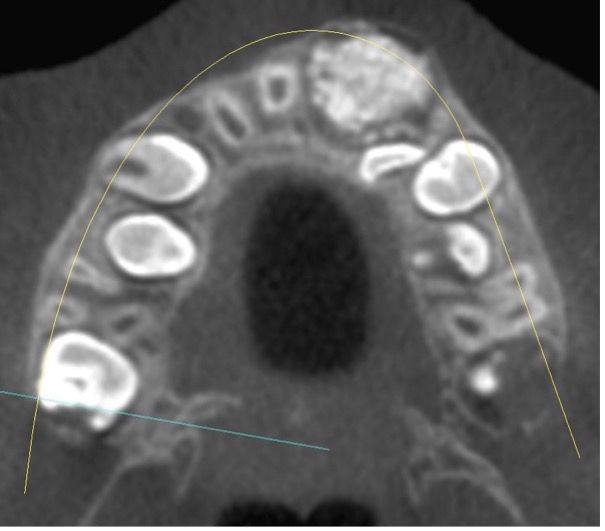

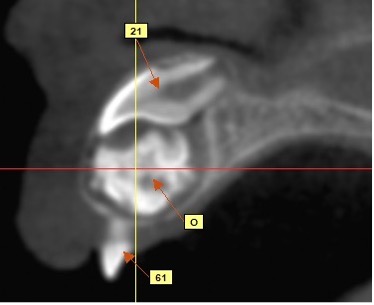

Panoramic radiography revealed a radiopaque entity within the maxilla, with an appearance consistent with an odontoma. (Fig. 2) There was evident displacement of teeth 21 and 22. Incidental findings included resorption of the distal aspect of primary tooth #55 secondary to ectopic eruption of #16. A cone beam CT scan was obtained for further characterization of the lesion. (Fig. 3)

Fig. 2

Fig. 3A

Fig. 3B

Fig. 3C

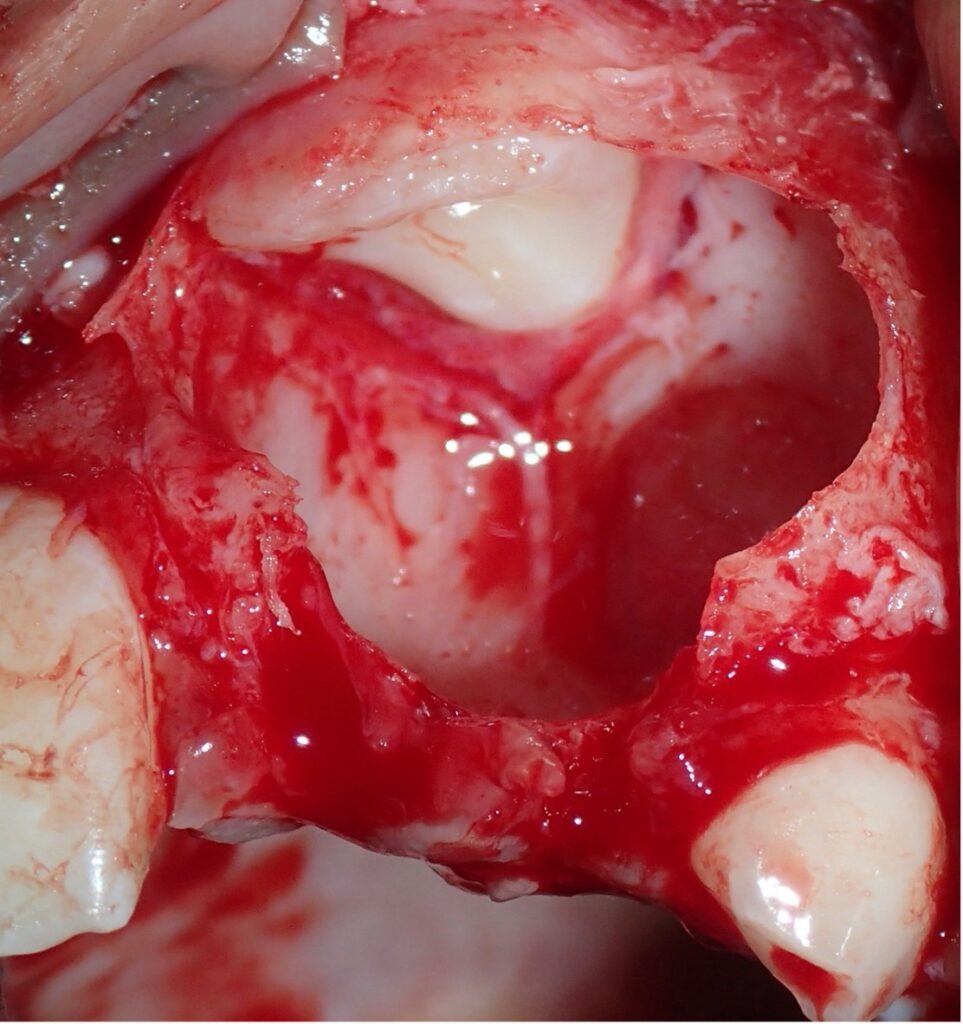

Surgery was performed under general anesthesia. Retained primary teeth #61 and 62 were removed. The lesion was excised with following elevation of a full thickness flap on the buccal aspect. (Fig. 4) The expanded buccal cortical bone was removed to provide access to the perimeter of the lesion. (Fig. 5)

Fig. 4

Fig. 5

Multiple fragments of tooth-like structure were curetted from the alveolus and submitted in formalin for pathologic examination. (Fig. 6) The surgical site was evaluated. and the displaced tooth #21 was visualized at the superior aspect of the defect (Fig. 7)

Fig. 6

Fig. 7

The site was cleansed, and flap closure was accomplished with resorbable sutures. A panoramic radiograph was taken one year following surgery, which exhibited successful initiation of eruption of both teeth # 21 and 22. (Fig. 8)

Fig. 8

DISCUSSION:

Odontomas may occur in various morphologic types. Compound odontomas occur with the greatest frequency, with a predilection for the maxillary incisor and canine region, while complex odontomas are most likely to be seen in association with mandibular second and third molars. While variation in the timing of dental eruption is common, significant deviations should alert the clinician to perform an appropriate radiologic study to investigate for the presence of a causative lesion or congenital absence of the tooth.5 All forms of odontoma are treated with surgical enucleation. Surgery is curative, and the lesion has no known recurrence tendency. Meticulous attention during removal of compound odontomas is essential to ensure that all the lesion is excised. Bone grafting of the alveolar defect is not indicated. In most cases, the eruption of teeth that have been delayed will progress spontaneously following removal of the lesion; however, secondary surgical exposure and orthodontically guided eruption may be required in some case.6

CONCLUSIONS:

Odontomas represent the most common lesion in paediatric patients. Lack of timely eruption of permanent teeth and expansion of the alveolar process should alert the dental clinician to perform an appropriate radiographic study. Timely diagnosis and management of odontomas is important to facilitate complete eruption of the permanent dentition.

Oral Health welcomes this original article.

References

- Neville BW, Damm D. et. al. Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology, Fourth Edition. Elsevier, 2016

- Marx RE, Stern D. Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology: Quintessence, 2003. Print.

- Kaban LB, Troulis MJ. Paediatric Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery: Saunders, 2004. Print.

- Tamimi D., Petrikowski CG et. al. Diagnostic Imaging Oral and Maxillofacial, Second Edition.

- Elsevier, 2017 Maltagliati A. et. al. Complex odontoma at the upper right maxilla: Surgical management and

- Isola G. et. al. Association between odontoma and impacted teeth. J Craniofac Surg. 2017 May;28(3):755-758.

About the Author

Marshall Freilich has been a board-certified oral and maxillofacial surgeon since 1999. He is staff surgeon at Humber River Hospital, and maintains a private practice in Toronto, Canada.

RELATED ARTICLE: Management of Benign Odontogenic Lesions in the Paediatric Patient