Introduction

Displaying an optimal amount of gingiva while smiling is one of the critical elements in the ideal conceptual smile.1 In orthodontics and aesthetic dentistry, it is not rare to encounter a patient complaining of a ‘gummy smile’ or excess gingiva on smiling.2 Therefore, it is essential to understand the etiology, biology and management strategies associated with this clinical condition.3 These fundamental principles will increase the probability of achieving an aesthetic and healthy outcome for our patients.

This article will review the diagnostic criteria relating to excessive gingival display and the appropriate and differing management strategies. We will also present the management of an interdisciplinary case of excess gingival display utilizing digital technology in the diagnosis, planning and treatment. These technological advancements are rapidly contributing to the evolution of aesthetic dentistry technology.4 When used appropriately digital technology can undoubtedly improve communication, planning and treatment execution in contemporary esthetic crown lengthening procedures.

Contemporary smile elements and the variables of visual perception

An aesthetic harmonious smile results from synchronized coordination of a complex of craniofacial structures. Indeed, there are basic, and universally recognized principles on what factors contribute to a beautiful smile.5,6 While some gingival display can be considered attractive, think Julia Roberts as an example, excessive gingival display of more than 4mm from the inferior border of the upper lip to the gingival margin of the maxillary incisors has been scientifically studied and considered “unattractive” by dentists and laypeople.7 However it is important to remember that the perception of the ideal of a smile is subjective with cultural and ethnic variables.8 Those variables are listed in Table 1.

Table 1: Variables of visual perception on smiles

Table 2: Classification of APE by Coslet et al.25

Etiology of excessive gingival display

Identifying an etiology is critical in establishing a correct diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment plan. The etiology can be singular but also multi-factorial. The etiology can be complex, and it is essential to use the appropriate diagnostic records. A cephalometric analysis, combined with static and dynamic photography, is imperative to assess the craniofacial region’s soft and hard tissue components that relate to the gingival display at rest and during smiling. The orthodontist may be the most suitable clinician to assess the different etiological factors and contribute to precise treatment planning and management for reducing excess gingival display.11 Common etiological factors include the following:

1. Increased vertical growth of the maxilla can result in excessive gingival display (skeletal origin). This can be a common feature in patients with a hyperdivergent growth pattern. Treatment of choice for this skeletal problem is a maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy. This treatment is interdisciplinary involving the orthodontist and maxillofacial surgeon along with a periodontist as necessary.

2. Hyper-mobility of muscles of facial expression can also lead to excessive gingival display. Average lip movement from the rest to full smile is 6-8mm.12 Botox can also be a helpful adjunct to immobilize hyper-mobile elevator smile muscles and, therefore the upper lip.13 botulinum toxin type A (BTX-AA short upper lip can cause excess gingival display.11 The upper lip lengthens with age, and the average distance from the base of the nose to the inferior border of the upper lip for females and males is 20-22 and 22-24mm respectively.14,15 Depending on the criteria, these can be intervened surgically by ‘lip repositioning’ utilizing partial thickness flaps taking epithelial discard to deepen the vestibule and positioning the muscle attachment more apically.16

3. Altered active or passive eruption of teeth may result in more gingival display. In simple terms ‘normal’ active eruption is the occlusal movement of the tooth out of the alveolus. This occurs until the CEJ as approx. 1-5-2mm from the osseous crest. A process of ‘passive eruption’ is the apical migration of the dento-gingival junction. This occurs until the gingival margin is 1mm coronal to the CEJ.17 Its important to remember that in growing patients, this passive migration continues until early adulthood at approximately 16 years of age.18 So reduced active and passive eruption can occur in some patients leading to excessive gingival display. Anterior maxillary dentoalveolar extrusion and/or protrusion can alter the gingival smile display due to the intimate nature of the maxillary teeth and the lips. A good understanding of the detail aesthetics is required to treat these cases.19-22 Depending on the treatment objectives, orthodontic treatment can correct the dento-alveolar extrusion or alternatively a surgical segmented osteotomy may be required to re-establish the ideal soft and hard tissue architecture. Also, short clinical crowns can give the perception of excess gingival display due to the pink/white imbalance of full smile. In addition, there are also obvious causes of excess gingival display such as inflammatory reaction of the gingival due to local and systemic factors.

Classification of altered active and passive eruption

The most commonly used classification was published by Coslet et al. considering two main factors; the amount of keratinized gingiva apical to the teeth (Type 1: wide gingiva, Type 2: normal gingiva) and the relationship between the cementoenamel junction and its corresponding alveolar crest (A: normal (alveolar crest is from 1.5-2.0mm from CEJ; B: alveolar bone is at the level of CEJ).23 However, recently a modification of the classification has been proposed by incorporating ‘altered active eruption’ for the sub-group B of Coslet classification, where CEJ is at the level of the alveolar crest as it may be considered as an altered active eruption.24 A different surgical approach is required for each subgroup. These interventions vary from gingivectomy with or without an apically positioned flap to osseous reduction with or without an apically positioned flap. An apically positioned flap is required when the width of the keratinized tissue is inadequate (< 2mm).

Periodontal Management

Esthetic crown lengthening is a procedure with a primary goal of exposing more tooth structure to achieve an ideal proportion in cases with an excessive gingival display. The goal of the procedure is to establish a normal mucoperiosteal relationship and gain a predictable surgical outcome. That is, to re-establish the supra-crestal attachment apparatus.26 The amount of alveolar bone to be removed must be estimated before surgery(ideally), keeping the positive architecture intact and harmonious along with neighbouring dentition. However, the reality of clinical situation is that one cannot predictably determine how much of bone removal is required as the radiographs do not tell the labial bone levels or thickness. Even CBCT does not help in estimating those in detail either. Probing the crestal bone levels with a periodontal probe with administration of local anesthetic is only way to estimate them. But then, due to additional appointment with administration of local anaesthetics, it is not always the case that we perform the ‘sounding procedure’. Rather the patients are informed that it is likely that bone removal would be required. If a case is multi-disciplinary, communication between treating clinicians is critical. Appropriate digital technology can be utilised in planning and communication in these cases. After a precise diagnosis and treatment plan, a 3D printed surgical guide can be fabricated and used as a ‘blueprint’ during treatment. From the literature standpoint, the supra-crestal attachment apparatus is considered 2 mm and 1 mm in the depth of the sulcus.27 However, these represent average numbers with high individual variation and, therefore, they need to be adapted to each case.28 Also, the incision design must be individualized based on the patient factors such as individual gingival phenotype(thin vs. thick) and degree of scalloping (flat vs. scalloped). Incision should involve the interproximal regions in case of wide papilla and if the interdental papillae are narrow an highly scalloped, the papillae must be preserved.24 Deas et al. reported soft tissue’s tendency to rebound during healing if the flap is positioned too close to the alveolar crest.29 The distance of 3 mm between flap margin and crest of alveolar bone flap and osseous margin showed minimal soft tissue changes after surgery.23,30,31 However, the osseous reduction is not always required, and an internal bevel incision with either 45-degree (average to thick tissue) or 90-degree (thin tissue) may be sufficient. A clinician must clearly define ideal gingival architecture in relation to the presenting tooth morphology. Gingival symmetry and the ideal zenith locations on the anterior maxillary teeth must be determined before the initial incision. Ideally, the gingival margins of the central incisors are either even or 1 mm apical to that of the lateral incisors.3 The gingival margins of canines are usually positioned 1 mm apical to the margins of the lateral incisors. The imaginary line drawn between the margins of canines must be parallel to the inter-pupillary line. After the healing of surgery, the marginal gingiva on the anterior teeth must be harmonious with the smile line of the patient.

A critical role of the virtual planning in multi-disciplinary esthetic crown lengthening

Esthetic crown lengthening usually involves a multi-disciplinary approach as it combines highly sophisticated surgical intervention with precisely planned orthodontic intervention and even on occasion full rehabilitation restorative treatment. Therefore, it is essential to plan a case with good communication not only to a patient but also among clinicians and laboratories involved.31

In the era of digital dentistry, it can be advantageous to use the appropriate digital hard and software for case planning. Each clinician can contribute to the treatment plan and create a blueprint for predictable and consistent outcomes for patients. Having a virtual plan for the final position of teeth combined with the necessary prosthodontic plan reduces the chance of any guesswork. Using digital smile design and digital wax-up, a precise 3D printed surgical stent can be fabricated. These steps are excellent adjuncts to traditional treatment methods of similar cases. In our opinion, the esthetic crown lengthening is one of the procedures where digital dentistry may be beneficial. An advanced surgical guide can simplify the surgical steps by incorporating not only the soft tissue component but also the ‘built-in’ supra-crestal attachment apparatus (biological width). A guide can give a surgeon a clear preview of the amount of resection on the osseous structures and clarifies the communication between a surgeon and orthodontist/prosthodontist/restorative dentist and transfers information more clearly.

Case report

Orthodontic Care

A 14-year-old female presented to the orthodontic clinic at the University of British Columbia, Faculty of Dentistry with a chief complaint of dental crowding and didn’t like her diastema. (Figs. 1A-D) There were no significant findings in her medical history. Extra-oral examination revealed a straight profile with a mild hyperdivergent growth pattern. Her upper lip was short (16 mm at rest) and was hypermobile on full smile. She displayed severe excess gingiva on smiling (+4mm). The dentition showed reduced clinical crown heights with a severely uneven pink/white balance. Intra-orally, she presented with a Class II subdivision left malocclusion and an overjet of 5 mm and a 60% overbite with a mild curve of Spee. The arch forms were tapered. There was mild lower anterior crowding, an anterior maxillary diastema and the lower midline was deviated to the left of the facial midline (3mm). The Bolton analysis revealed a mild mandibular excess. A pre-treatment digital smile design using Keynote on Mac as proposed by Coachman,32 revealed the possibility of the end result and also highlighted the excess gingival display and poor crown height to width proportionality. After discussions with the patient and her parents a consultation was arranged with the periodontist to discuss possible treatment options prior to starting treatment. An initial plan was to review the situation post orthodontic treatment as the patient would also be near to the end of growth and periodontal maturation as discussed earlier.33 The orthodontic treatment plan consisted of upper and lower fixed edgewise appliances, and biomechanically the use of intermaxillary elastics to correct the malocclusion. (Fig. 2)

Fig. 1A

Fig. 1B

Fig. 1C

Fig. 1D

Fig. 2

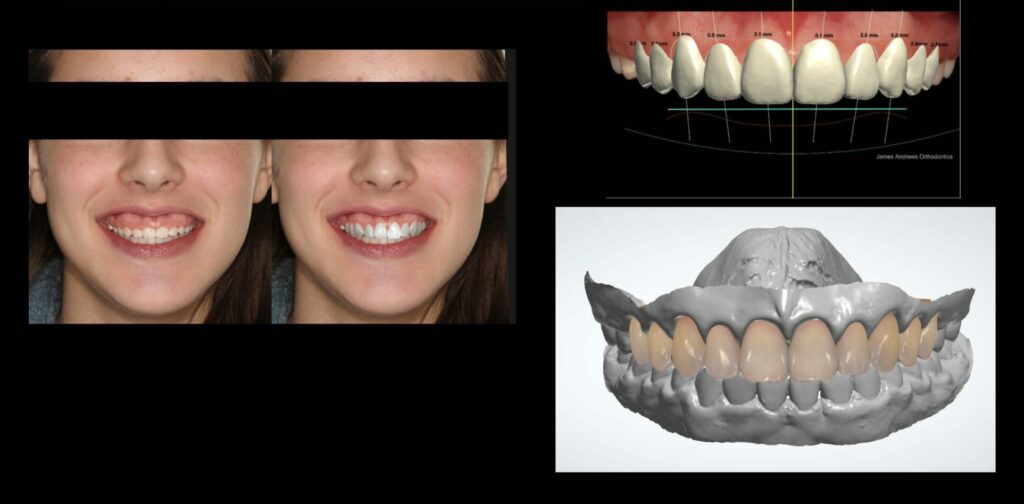

Orthodontic treatment took 27 months and 18 appointments. An ideal finish was challenging due to the excess gingival display, and it was decided to do some minor tooth movement using clear aligners post periodontal surgery. It is important to note that bracket placement is difficult in patients with altered passive eruption and aligners would not be a suitable appliance to use, due to the reduced surface area and clinical crown height. Post orthodontic treatment, (Figs. 3A-B), the orthodontist converted the 2D digital smile design to 3D utilising Trios (3Shape, Denmark) intra-oral scans, and the CAD 3Shape design studio to fabricate a digital wax up of the ideal tooth proportion for the upper maxillary teeth. (Figs. 4A-C)

Fig. 3A

Fig. 3B

Fig. 4A

Fig. 4B

Fig. 4C

On consultation with the periodontist, the anatomical parameters were evaluated using bone sounding and intra-oral radiography. Cone beam CT was not used due to ALARA principles, especially in a young patient. A surgical guide was designed via CAD/CAM software (3 shape design studio) utilising the digital wax up combined with the direct clinical and radiographic information. This guide was designed to transfer two critical information to the periodontist (JC) namely location of gingival margins and to indicate the supra-crestal attachment apparatus (3 mm). This precision guide was prepared using the FormLab 2B printer (FormLab Inc. 35 Medford St. Suite 201 Somerville, MA USA). Fit and design of the guide were confirmed on the 3D printed model and intra-orally before surgery. (Figs. 5A-D).

Fig. 5A

Fig. 5B

Fig. 5C

Fig. 5D

Periodontal care and surgical management

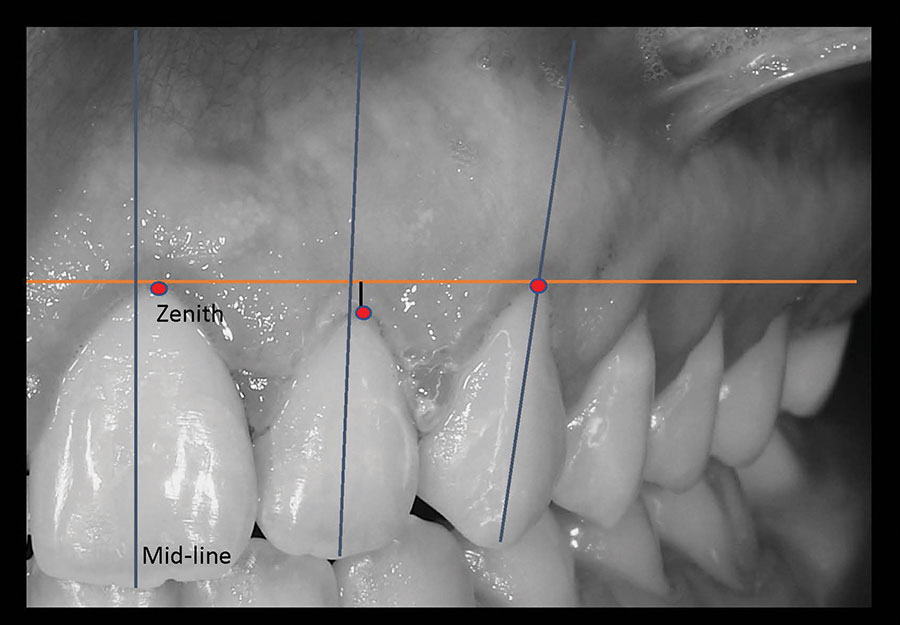

Patient’s periodontal conditions showed no abnormalities with 1-3 mm probing depths without any significant bleeding. Her gingiva was firm and pink, and her interdental papillae were intact. The amount of keratinized tissue was adequate (more than 5-7 mm) in the anterior maxilla. The amount of plaque was minimal, and the patient demonstrated good oral hygiene and home care. Review of her radiographs showed no significant findings. Sounding on each tooth were performed after the local anaesthesia to assess the bone level and confirm altered passive eruption. The bone level and possible cementoenamel junctions were confirmed to coincide. (Figs. 6A-C) She reported no clenching or bruxism, and clinically, there was no evidence of fremitus.

Fig. 6A

Fig. 6B

Fig. 6C

Local anesthetic with 4% articaine 1:200,000 epinephrine was applied as bilateral ASA, MSA, and PSA, along with palatal infiltration. The incision lines were marked by No.15C blades using the printed guide. (Figs. 7A-B) From these marking incision lines, the actual primary incisions were made without the guide. The scalloping inverse bevel incision creating ideal locations of zeniths on the central, lateral, and canines was made. The incision was continued to the maxillary molars to make the marginal gingival contour harmonious with her smile line and to avoid abrupt discrepancy between the gingival margins between the 1st/2nd premolars and the first molar. The incision was made considering the zenith of the central incisors, lateral incisors, and canines were respectively located 1 mm, 0.4 mm, and 0 mm from the teeth’ midline.34 Also, consideration of the vertical location of the margins of central incisors and canines were at the same level. The gingival margins of the lateral incisors were located 1 mm more coronal than those of the central incisors and canines.34 The blades were frequently changed to maintain the cutting efficiency. A flap was raised partially in the interdental papillae, and the full-thickness flap was raised only in the apical zones of the buccal surface. Using a guide, the amount of ostectomy was measured, and the osseous resection was performed, keeping a 3 mm distance between the newly established gingival margin and alveolar crest. The guide was inserted back and forth to confirm that the reduction was sufficient to avoid any soft tissue rebound.29 (Figs. 7C-D) The flap was repositioned and sutured with single interrupted sutures using 5-O polyprolene. (Fig. 7E) For pain management, ibuprofen (400 mg) was recommended every 4-6 hours without exceeding 3200 mg/day. To support home care, 0.12% chlorhexidine was prescribed with instruction to rinse mouth with 15 ml twice per day. Other appropriate post-operative instructions were given. The postoperative care visits were at 2 and 8 weeks. (Figs. 8 & 9) Complete soft tissue maturation may take up to six months.30,35 At 8 weeks, the ideal gingival architecture were established including the locations of the zenith in relation to the midline of the teeth. (Fig. 10) The patient and her parents were pleased with the result and no further intervention except orthodontic aligners were needed. (Figs. 11A-B)

Fig. 7A

Fig. 7B

Fig. 7C

Fig. 7D

Fig. 7E

Fig. 8

Fig. 9

Fig. 10

Fig. 11A

Fig. 11B

Conclusion

Understanding the fundamental features of the ‘ideal’ smile and the contributing craniofacial hard and soft tissues is critical in recognizing and establishing a correct diagnosis. However, smile can be subjective and patient input is mandatory to define the treatment goals. Identifying etiological factor(s) of the excess gingival display is also crucial in treatment planning and management. Incorporating digital technology in the different phases of treatment can clarify the communication between the patient and multiple clinicians involved. Virtual planning with the endpoint in mind can produce a tangible digital wax-up and smile prediction from which a precise 3D-printed surgical guide can be fabricated to encompass the appropriate information for modification of hard and soft tissue contours.

Oral Health welcomes this original article.

Acknowledgement: It is with great sadness that we mourn the death of David Kennedy. David fondly known as DBK by his students, was a dual trained Pediatric and Orthodontic Specialist and a Fellow in both Specialties with the Royal College of Dentists of Canada. After over 40 years in practice, he was a Clinical Professor with over 50 publications, and served as Co-Clinical Director for Graduate Orthodontics at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver. He will be dearly missed.

Acknowledgement: It is with great sadness that we mourn the death of David Kennedy. David fondly known as DBK by his students, was a dual trained Pediatric and Orthodontic Specialist and a Fellow in both Specialties with the Royal College of Dentists of Canada. After over 40 years in practice, he was a Clinical Professor with over 50 publications, and served as Co-Clinical Director for Graduate Orthodontics at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver. He will be dearly missed.

References

- Silberberg N, Goldstein M SA. Excessive gingival display – etiology, diagnosis, and treatment modalities. Quintessence Int. 2009;Nov-Dec;40((10)):809-18. PMID: 19898712.

- Waldrop TC. Gummy Smiles: The Challenge of Gingival Excess: Prevalence and Guidelines for Clinical Management. Semin Orthod. 2008;14(4):260-271. doi:10.1053/j.sodo.2008.07.004

- Allen EP. Use of mucogingival surgical procedures to enhance esthetics. Dent Clin North Am. 32((2):):307-30.

- Blatz MB, Chiche G, Bahat O, Roblee R, Coachman C, Heymann HO. Evolution of Aesthetic Dentistry. J Dent Res. 2019;98(12):1294-1304. doi:10.1177/0022034519875450

- Fradeani M. Copyright by Quintessenz Alle Rechtevorbehalten CLINICAL APPLICATION Evaluation of Dentolabial Parameters As Part of a Comprehensive Esthetic Analysis. Eur J Esthet Dent. 2006;1.

- Chiche GJ, Pinault A. Esthetics of anterior fixed prosthodontics. 1994:202.

- Kokich VO, Jr, Kiyak HA SP. Comparing the perception of dentists and lay people to altered dental esthetics. J Esthet Dent. 11:311-24.

- McLeod C, Fields HW, Hechter F, Wiltshire W, Rody W, Christensen J. Esthetics and smile characteristics evaluated by laypersons: A comparison of Canadian and US data. Angle Orthod. 2011;81(2):198-205. doi:10.2319/060510-309.1

- Sabri ROY. 8 Components of Balanced Smile. Jco. 2005;XXXIX(3):155-167.

- Machado AW. 10 Commandments of Smile Esthetics. Dental Press J Orthod. 2014;19(4):136-157. doi:10.1590/2176-9451.19.4.136-157.sar

- Seixas MR, Costa-pinto RA, Araújo TM De. Checklist of esthetic features to consider in diagnosing and treating excessive gingival display ( gummy smile ). 2011;16(2):131-157.

- Robbins JW. Differential-Diagnosis-and-Treatment-of-Excess-Gingival-Display.pdf. Pr Periodont Aesthet Dent. 1999;11((2):):

265-272. - Polo M. Botulinum toxin type A (Botox) for the neuromuscular correction of excessive gingival display on smiling (gummy smile). Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 2008;133(2):195-203. doi:10.1016/j.ajodo.2007.04.033

- Peck S, Peck L, Kataja M. The gingival smile line. Angle Orthod. 1992;62(2):91-100; discussion 101. doi:10.1043/0003-3219(1992)062<0091:tgsl>2.0.co;2

- Peck S, Peck L. Selected aspects of the art and science of facial esthetics. Semin Orthod. 1995;1(2):105-126. doi:10.1016/S1073-8746(95)80097-2

- Aly LA HN. Botox as an adjunct to lip repositioning for the management of excessive gingival display in the presence of hypermobility of upper lip and vertical maxillary excess. Dent Res J (Isfahan). 2016;Nov-Dec;13((6):):478-483. doi: 10.4103/1735-3327.197039.

PMID: 2818. - Brizuela M ID. Excessive Gingival Display. StatPearls [Internet] Treasure Isl StatPearls Publ. 2022;Mar 9(PMID: 29262052.).

- Volchansky A, Cleaton-Jones P. The position of the gingival margin as expressed by clinical crown height in children aged 6–16 years. J Dent. 1976;4(3):116-122. doi:10.1016/0300-5712(76)90011-7

- Sarver DM, Ackerman MB. Dynamic smile visualization and quantification: Part 1. Evolution of the concept and dynamic records for smile capture. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 2003;124(1):4-12. doi:10.1016/S0889-5406(03)00306-8

- Spear FM, Kokich VC, Mathews DP. Interdisciplinary management of anterior dental esthetics. J Am Dent Assoc. 2006;137(2):160-169. doi:10.14219/jada.archive.2006.0140

- Sarver DM. Interactions of hard tissues, soft tissues, and growth over time, and their impact on orthodontic diagnosis and treatment planning. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 2015;148(3):380-386. doi:10.1016/j.ajodo.2015.04.030

- Magne P, Gallucci GO, Belser UC. Anatomic crown width/length ratios of unworn and worn maxillary teeth in white subjects. J Prosthet Dent. 2003;89(5):453-461. doi:10.1016/S0022-3913(03)00125-2

- Ingber FJC, Rose LF CJ. The “Biological Width”- A concept in periodontics and restorative dentistry. Alpha-Omegan. 1977;10:62-65.

- Ragghianti Zangrando, M.S., Veronesi, G.F., Cardoso, M.V., Michel, R.C., Damante, C.A., Sant’Ana, A.C., de Rezende, M.L. and Greghi SL. Altered Active and Passive Eruption: A Modified Classification. Clin Adv Periodontics,. 2017;7: 51-56.https://doi.org/10.1902/cap.2016.160025.

- Coslet JG, Vanarsdall R WA. Diagnosis and classification of delayed passive eruption of the dentogingival junction in the adult. Alpha Omegan. 1977;Dec;70((3):):24-8. PMID: 276255.

- Caton JG, Armitage G, Berglundh T, et al. A new classification scheme for periodontal and peri-implant diseases and conditions – Introduction and key changes from the 1999 classification. J Periodontol. 2018;89(S1):S1-S8. doi:10.1002/JPER.18-0157

- Gargiulo AW, Wentz FM OB. Dimensions and relations of the dentogingival junction in humans. J Periodontol. 1961;32:261-267.

- Dello Rousso. Biologic width and crown lengthening. J Periodontol. 1993;64((3):):240-241.

- Deas DE, Moritz AJ, McDonnell HT, Powell CA, Mealey BL. Osseous Surgery for Crown Lengthening: A 6-Month Clinical Study. J Periodontol. 2004;75(9):1288-1294. doi:10.1902/jop.2004.75.9.1288

- Brägger U, Lauchenauer D LNJCP 1992 J-63. doi: 10. 1111/j. 160.-051x. 1992. tb01150. x. P 1732311. Surgical lengthening of the clinical crown. J Clin Periodontol. 1992;Jan(;19(1):):58-63. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1992.tb01150.x. PM.

- Lai JY, Silvestri L, Girard B. Anterior esthetic crown-lengthening surgery: a case report. J Can Dent Assoc. 2001;67(10):600-603.

- Coachman C, Georg R, Bohner L, Rigo LC, Sesma N. Chairside 3D digital design and trial restoration workflow. J Prosthet Dent. 2020;124(5):514-520. doi:10.1016/j.prosdent.2019.10.015

- Volchansky A, Cleaton-Jones P. Clinical crown height (length) – a review of published measurements. J Clin Periodontol. 2001;28(12):1085-1090. doi:10.1111/J.1600-051X. 2001.281201.X

- Chu SJ, Tan JH, Stappert CF TD. Gingival zenith positions and levels of the maxillary anterior dentition. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2009;21((2):):113-20. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8240.2009.00242.x. PMI.

- Larjava H. Oral Wound Healing : Cell Biology and Clinical Management. H. oboken: John Wiley & Sons; 2012.

About the Authors

Jae Chang maintains a private practice – Etobicoke Periodontics (etobicokeperio.ca) – in Ontario and practices at Dental Specialists in Toronto, a multi-specialty clinic in North York, Ont. He is a fellow of the Royal College of Dentists of Canada in Periodontology. He obtained his DDS from the University of Western Ontario in 2000, and completed Master of Oral Implantology at the J.W. Goethe University in Frankfurt, Germany in 2015. He completed his MSc degree in the Craniofacial Sciences and Specialty training in the Periodontology at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver in 2021. Contact: jw.chang@dentistry.ubc.ca.

Jae Chang maintains a private practice – Etobicoke Periodontics (etobicokeperio.ca) – in Ontario and practices at Dental Specialists in Toronto, a multi-specialty clinic in North York, Ont. He is a fellow of the Royal College of Dentists of Canada in Periodontology. He obtained his DDS from the University of Western Ontario in 2000, and completed Master of Oral Implantology at the J.W. Goethe University in Frankfurt, Germany in 2015. He completed his MSc degree in the Craniofacial Sciences and Specialty training in the Periodontology at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver in 2021. Contact: jw.chang@dentistry.ubc.ca.

James Andrews maintains a private practice in Perth, Western Australia (andrewsorthodontics.com.au). He is a Fellow of the Royal College of Dentists of Canada in Orthodontics. He obtained his BDS from the University of Dundee, UK. He completed his MSc degree in the Craniofacial Sciences and specialty training in Orthodontics at the University of British Columbia in 2021. Contact: hello@andrewsorthodontics.com.au.

James Andrews maintains a private practice in Perth, Western Australia (andrewsorthodontics.com.au). He is a Fellow of the Royal College of Dentists of Canada in Orthodontics. He obtained his BDS from the University of Dundee, UK. He completed his MSc degree in the Craniofacial Sciences and specialty training in Orthodontics at the University of British Columbia in 2021. Contact: hello@andrewsorthodontics.com.au.

Larjava Hannu Larjava graduated from the University of Turku, Finland, in 1978 (DDS) and earned his PhD from the same institution in 1984. He then specialized in periodontics (1987) followed by NIH postdoctoral fellowship in Washington DC.

Larjava Hannu Larjava graduated from the University of Turku, Finland, in 1978 (DDS) and earned his PhD from the same institution in 1984. He then specialized in periodontics (1987) followed by NIH postdoctoral fellowship in Washington DC.

RELATED ARTICLE: The MINIETM Laser Approach to Esthetic Crown Lengthening and Excellent Aesthetics!