Case study: January 2021

For four years, as dental students enter the four walls of their respective faculties, they are taught how to protect and save the teeth and smiles of their patients. Today, dentists continue to do what they were taught, some decades ago. However, the current COVID-19 pandemic highlights areas not taught regarding dentistry’s role in abuse recognition and domestic violence prevention.

Often dental health care professionals (DHCP) are first responders amongst all health care professionals (HCPs) for patients of all ages, especially those suffering traumas of abuse and neglect, but the DHCP’s lack of abuse recognition can impact patients in a dramatic way. Current pandemic quarantine and isolation protocols have set a “new normal” to all HCP’s learning curves! COVID-19 has forced abused victims, regardless of age, being secluded in homes with their abusers. In many ways, our current society has a pandemic (of domestic violence) within a pandemic (COVID-19).

Patients (children, spouse / partners and seniors) are “locked down” in their own homes with abusers with nowhere to run for safety yet the severity and intensity of abuse continues to increase with time.1 Today’s abusive verbal shouting can evolve to a slap across the face; then possible choking; a punch in the face; a blow to the head with a solid object; eventually (all too often) resulting in a homicide. Canada averages 2.5 women killed by intimate partners every 7 days, with 80% adult and 59% child victims.2 We hear media comments like “I never thought he would do this. He was such a great person, a quiet neighbour”.

Studies consistently show that of all abuse (emotional, sexual, psychological, etc.) physical abuse accounts for about 35% of all abuse. Important for the DHCP, 65% occurs in the head and neck area (the dental health care professional’s domain) and 24% on the limbs (arms and legs), resulting in about 89% of all physical abuse being easily viewable by any HCP3 – if they know what to look for.

In Ontario, professionals who work with or treat children under 18 years of age or institutionalized patients regardless of age are mandated to report (by Law) their suspicions of abuse to the proper authorities (Police, Children’s Aid Society, Crime Stoppers, etc.) under Ontario’s (CYFSA) Child, Youth and Family Services Act (2017).4 CYFSA has an excellent pamphlet (free) detailing the key “Duty to Report” mandate and its responsibilities for all HCPs.5

Penalties can reach $5,000 under the Act for HCPs not reporting suspicions of abuse.6 Afterwards, a report can be made to the HCP’s Regulatory body (for dentists, the Royal College of Dental Surgeons of Ontario {RCDSO})7 where a charge of “professional misconduct” may be applied under the Regulated Health Professions Act, 1991 (RHPA). This can result in a fine of up to $50,000 with possible revocation of the DHCP’s license for a period of time. According to the CYFSA (s.125 (8)) even dental corporation “directors, officers or employees of (the) corporation also have a legislated duty to report if they have knowledge that a child who is under 16 is or may be in need of protection”.

All HCPs are not required to investigate and “prove” abuse. That is a job for the multi-disciplinary investigative team. All that the CYFSA asks is for the HCP to simply report their suspicion of abuse. Yet studies show about 75% of all DHCPs are not taught or trained in recognizing signs and symptoms of victim abuse8 while cases of abuse and domestic violence are escalating due to COVID-19’s “stay at home” and physical isolation protocols.9

This lack of DHCP’s recognition training may be the reason for an escalation in numbers as patients begin to slowly return for regular dental care with governmental restrictions being lowered. However, abuse recognition can be easily started just by updating medical histories – if HCPs ask the right questions. During every new patient or emergency examinations and all recare (6-month “recalls”) visits, DHCPs follow existing RCDSO recordkeeping guidelines by routinely asking medical (heart, liver, kidneys, etc.) plus social lifestyle questions (smoking, drinking, recreational drugs taken, venereal disease status, etc.) to update changes from previous records.

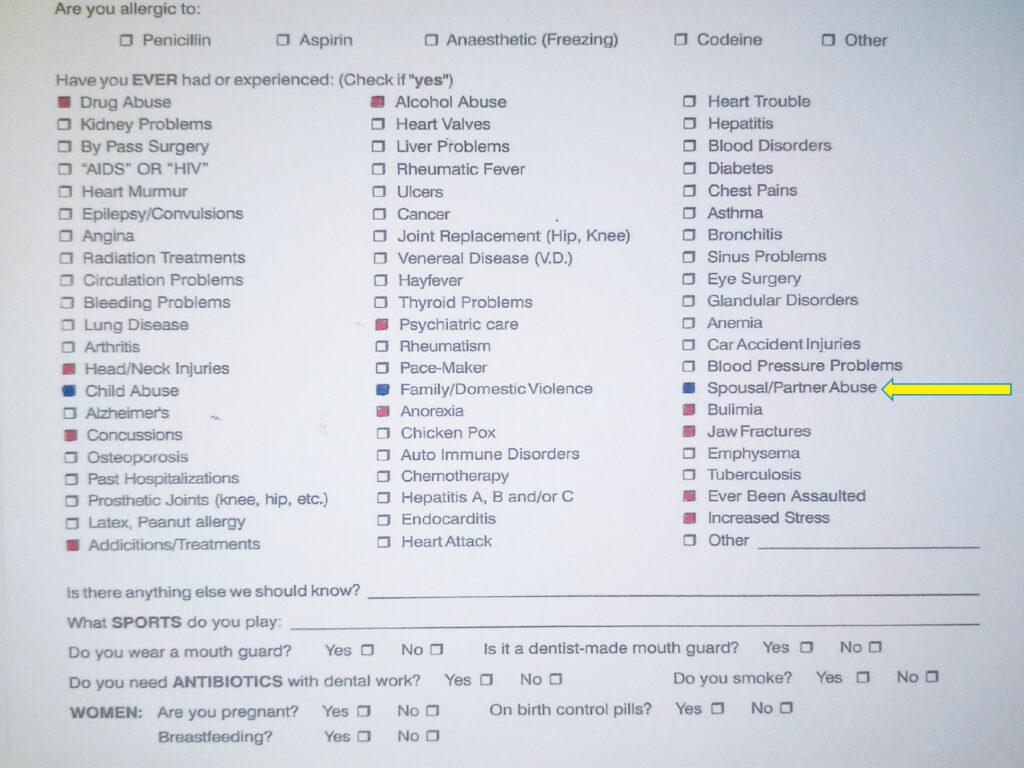

However, DHCPs should be trained to also ask key abuse-related questions such as: are you or have you ever been a victim of child, spousal/partner, or senior abuse / assaults? Corollary questions associated with abuse / assaults include: drug / alcohol abuse; head / neck injuries; concussions; psychiatric care; anorexia; bulimia; jaw fractures; increased stress; addiction treatment;–even asking “ever been assaulted”? Personal studies over 30 years of dental practice resulted in a surprising 41% (+/- 2%) of all new and emergency patients checking off (at least) one of the initial 3 abuse questions (blue)–or three or more of the eleven corollary questions (red) on our medical history chart (Photo 1).10

Photo 1

To assure and guarantee patient privacy, the Personal Health information Protection Act, 2004 (PHIPA) and Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA) are mandated by the RCDSO.11 To properly abide by these regulations, all HCPs should ask all patients these questions in the privacy of the treatment operatory – without a guardian present.12 Ironically, new COVID-19 protocols made this easier by insisting guardians remain outside of the dental operatory, even for children.13 Continuing educational programs for DHCPs on all these aspects are available via the Ontario Dental Association’s (ODA) CE webinar series and is a Core 1 category course.14

Case Report

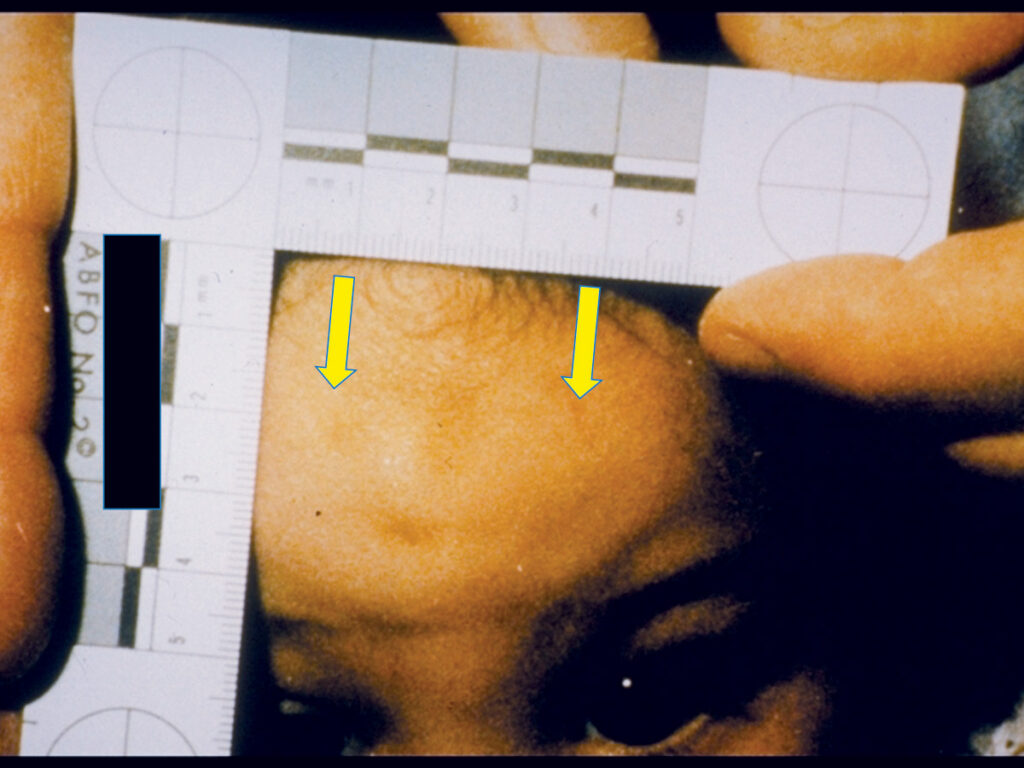

A grandfather reported to local police that he suspected his grand-daughter (2 years, 3 months of age) may be a victim of abuse; that he was on his way to a local hospital emergency department with his grand-daughter. A local “Child Abuse Branch” police officer asked that the author report to the emergency room for a dental forensic consultation. The child appeared with a traumatic head bruise (Photo 2)15 on her forehead. The bruise was a unique oval pattern. It was reported by the mother that the child “fell down the stairs”.

Photo 2

To the trained investigative eye, the bruise was suspected as not being a result of a fall down the stairs, but of a possible bite-mark. It was oval in shape measuring about 3 cm in diameter eye-tooth to eye-tooth, a perfect example of a suspicious injury that all DHCPs should subsequently reported to local authorities under the mandated CYFSA’s “duty to report”.16

As a multi-disciplinary (dentist, emergency room nurses and medical doctors, police and Children’s Aid Society in-take workers) team member and investigator, dentists are allowed to examine the entire body from head to foot. After a precise pattern-injury and dental work-up, a total of 13 bite-marks were found on the child’s body, with three bite-marks in the vaginal area. The patterns were confirmed as a cigarette burn plus 13 bite marks. The bite mark patterns were confirmed to be: 1) a bite mark; 2) a human bite-mark, compared to an animal (pet dog or cat) bite; 3) from a human adult (compared to a child); and 4) all from the same individual.

The multi-disciplinary investigative team subsequently found other suspicious injuries, with bruises in various stages of healing, colours and patterns resulting in the team concluding that these were abusive injuries that occurred: 1) within the last 2-7 days; 2) some as possible human bite-marks on various parts of the body, including on the child’s buttock; (Photo 3)17; and 3) possible cigarette burn on the sole of the foot. (Photo 4)18

Photo 3

Photo 4

Police executed a Collection of Dental Evidence Warrant19 for several family members, all Persons of Interest (POI) in this case, with the subsequent gathering of Aluwax® bite registrations, dental impressions and intra and extra-oral photographs. Examination and evaluation of this evidence using various dentally-related techniques, it was concluded on the balance of probability, that one person, distinct from all other POIs, was the abuser and biter. This lead to the conviction on charges of aggravated and sexual assault by the mother’s live-in boyfriend plus with the mother was also charged with knowingly allowing this abuse to occur on her child.

Without a trained dentist as a member of a multi-disciplinary investigative team, the 13 bite marks may not have been recognized as bite marks and the sexual assault charge may not have been added to the initial assault charge.

The author has had cases where injuries from various solid objects left a distinct pattern, such as belt buckles, kitchen instruments, sports equipment, etc. If a specific object was located by law enforcement or the CAS, many times it could be matched to the patterned bruise.

DHCPs can be key to abuse recognition because patients seek dental treatment for even minor injuries or trauma and routinely return on a regular basis (every 6-months) for follow-up treatment. As previously mentioned, 89% of abusive physical injuries occur are easily viewable by any HCP. With this in mind, all (D)HCPs should be aware that the (Canadian) National Clearinghouse on Domestic Violence (DV)20 2020 statistics indicated that:

- 25% of all violent crimes reported to police involve family violence;

- 70% of police-reported family violence victims are girls or women;

- Police-reported rates of intimate partner violence (IPV) are highest among women aged 25 to 34 years;

- 25% of all police-reported violence against children / youth are committed by a family member, with girls four times more likely than boys to be victims of familial sexual assault or other sexual offences;

- 65% of spouses accused of homicide had a history of family violence that involved divorce, separation or estrangement from their partner.

In 1997, DV was formally recognized as a public health issue, yet organizations note few health care faculties teach abuse recognition in their undergraduate curriculum even though DV represents about 26% of all reported 9-1-1 police calls; with 46% of all victims having physical injuries 84% of the time when abusers bit and/or hit.

COVID-19 has “led to increased rates of domestic violence” and DV police calls increased by 75.6% with responses at a 79.8% increase from the same month last year (2019).22 Statistics also show only 20% of women make (9-1-1) calls; 80% never call for fear of increased harm if caught by abusers.23 Since March 2020, COVID-19 protocol asked everyone to “stay home.” Women’s shelters and non-profit hot line calls saw a rise of “239% from March to April then in May, another 417% increase, with June’s numbers trending in a similar fashion.24

Dental clinical indicators of abuse include:

- Fractured, broken, chipped, lost, decayed teeth 20%

- Intra-oral cuts or lesions 5%

- Jaw fractures 7%

- Bruises on head and neck 21%

- Lip cut or swollen 29%

- Neck strangulation marks 14%

With such statistics and 89% of all physical abuse easily viewable, some dental faculties still continue to not include abuse recognition in their undergraduate curriculum.26

VEGA (Violence, Evidence, Guidance, and Action) is a project that created pan-Canadian, evidence-based guidance and education resources to assist healthcare and social service providers in recognizing and responding safely to family violence. VEGA developed resource funding from the Public Health Agency of Canada in collaboration with 22 national organizations, focusing on three main types of family violence: child maltreatment, intimate partner violence, and children’s exposure to intimate partner violence; developing an online platform of education resources comprised of learning modules, interactive educational scenarios and a Handbook.27

Another excellent HCP resource is available from the Centre for Research and Education on Violence Against Women and Children at Western University in London, Ontario. They provide courses on recognition and various pamphlets as educational aids.28

Both the RCDSO29 and Ontario Dental Association (ODA)30 have DHCP resources on abuse recognition, CE courses (Core 1) and webinars via their respective websites, updated as needed from Ontario’s Minister of Health.

Conclusion

April is “Dental Health Month” when DHCPs educate the public on prevention of dental oral problems and better dental health. October is recognized as “Child Abuse Month” assisting the public to recognize signs and symptoms of child abuse. Child abuse has been called a “state of emergency”31 worldwide suggesting that dental faculties dedicate October to educating all undergrad students on the mandated roles in abuse recognition for children under the age of 18 years.

After 4+ decades as a Court Expert Witness throughout North America, educating both health care and law enforcement professionals on what the profession of dentistry can bring to the forensic table, one personal conclusion persists, that each case assists 2 individuals: 1) the abused victim (removing them from an abusive situation) and 2) the abuser (to get professional help ending the cycle of violence). In my opinion, Canadian dental faculties should be mandated by the respective Regulators to immediately include the signs / symptoms of abuse recognition and DV preventive programs to undergrads.

The ODA has a Core 1 webinar program for all DHCPs reinforcing the key message that even days after abusive trauma, trained DHCPs should recognize abusive signs and symptoms and remain suspicious of all ongoing bruises and report suspicions of abuse immediately to authorities as the CYFSA mandates (CYFSA, s 125 (2)). DHCPs should also be assured that even if their suspicion is wrong, the CYFSA also mandates that as long as the report is made in “good faith”, the DHCP is protected (by Law) from any liability.32

All HCPs, regardless of their modality, should approach each patient / client as a member of their own family, doing what they would want someone else to do for their family member under similar suspicious circumstances.

Dr. Peter Jaffe from the University of Western Ontario stated it best. “You have to get over the issue of thinking it’s not your business because when it comes to an issue of an individual’s safety and well-being, then domestic violence has to be seen as everyone’s business. Overcome your emotions. It’s NOT all about you / your office”.33

References

- Ontario Association of Children’s Aid Societies (OACAS) – www.oacas.org

- CBC News, September 25, 2019.

- American Society of Forensic Odontology – www.asfo.org

- Child, Youth & Family Services Act (2017), CYFSA s. 125 (5), (8), (9).

- CYFSA, – “Reporting Child Abuse and Neglect: It’s Your Duty” – www.serviceontario.ca/publications. Publication #026517.

- CYFSA, s. 125 (5), (8).

- Royal College of Dental Surgeons of Ontario (RCDSO) – www.rcdso.org

- Journal of Dental Education, Vol. 73, No 4 – April 2008.

- OACAS Newsletter – July 2, 2020 – www.oacas.org

- Personal office Medical History chart – Dr. Stechey.

- PIPEDA & PHIPA.

- Dr. Harriett MacMillan – https://vegaproject.mcmaster.ca/home

- COVID Protocol, MOH & RCDSO.

- Ontario Dental Association, CE Webinars – www.oda.ca

- Personal Files of Author (Dr. Frank Stechey).

- CYFSA, s. 125 (2).

- Personal Files of Author(Dr. Frank Stechey).

- IBID.

- Criminal Code of Canada, s.487.092.

- Government of Canada; https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/health-promotion/stop-family-violence/learn-about-family-violence-including-rates-impacts-risks.html

- Statistics Canada – https://www.150.statcan.gc.ca

- Ontario Association of Children’s Aid Societies (OACAS) – July 14, 2020 newsletter – www.oacas.org

- Hamilton Police Services – The Spectator – January 20, 2018.

- OACAS, July 2nd 2020 newsletter – www.oacas.org

- Journal of Dental Education, Vol. 73, No 4 – April 2008.

- IBID.

- VEGA, McMaster University Medical Centre, https://vegaproject.mcmaster.ca/home

- Western University, CREVAWC – www.learningtoendabuse.ca

- Royal College of Dental Surgeons of Ontario – www.rcdso.or – 1-800-565-4591.

- Ontario Dental Association – www.oda.ca – 1-800-387-1393.

- Ontario Dental Nurses and Assistants Association (ODNAA) Journal; Vol.5 No. 4; October – December 1999; p16 – 18.

- CYFSA – s.125 (10).

- Dr. Peter Jaffe, Western University, January 2019.

About the Author

Dr. Frank Stechey Now retired from general practice after more than 45 years, had special interests in both sport and forensic dentistry. His forensic dental experience as a Court expert witness involved civil and criminal cases of: homicide, mass disaster training and response, product liability but especially cases of domestic violence, partner/spousal, senior and child abuse. He was a consultant for many children’s hospitals, Children’s Aid Societies, retirement homes, hospitals and municipal, provincial / state & federal police services and is recognized as a Fellow in eight international organizations including the International College of Dentists and the American Academy of Forensic Sciences and lectured to health care & law enforcement professionals throughout North America.

Dr. Frank Stechey Now retired from general practice after more than 45 years, had special interests in both sport and forensic dentistry. His forensic dental experience as a Court expert witness involved civil and criminal cases of: homicide, mass disaster training and response, product liability but especially cases of domestic violence, partner/spousal, senior and child abuse. He was a consultant for many children’s hospitals, Children’s Aid Societies, retirement homes, hospitals and municipal, provincial / state & federal police services and is recognized as a Fellow in eight international organizations including the International College of Dentists and the American Academy of Forensic Sciences and lectured to health care & law enforcement professionals throughout North America.

RELATED ARTICLE: Dental Hygiene Care for Survivors of Childhood Abuse