Abstract

This case report presents a novel intramuscular injection directed at the lateral pterygoid muscles as a potential treatment for Tinnitus in a TMD-related pain patient. The authors present a clinical case of a chronic TMD-related pain patient with chief complaints of jaw pain and tinnitus. The patient presented with additional symptoms, including ear pain, chewing pain, neck pain and shoulder pain. A TMD diagnosis was obtained using the RDC/TMD Criteria. Upon completing the clinical assessment, an intramuscular injection using a commonly available local anaesthetic injected through the lateral pterygoid muscle eliminated the patient’s tinnitus. Following the injection, the patient was prescribed a new set of complete upper and lower dentures with a modified vertical dimension of occlusion (VDO). The patient was followed up after 1-month, 3-months, and 20-months to assess the outcome. The patient experienced rapid and long-lasting pain relief allowing for the complete elimination of tinnitus. This was done with the objective of relaxing the muscle with the subsequent breaking of the pain cycle with the use of a local anaesthetic. This technique may be an effective treatment for TMD-related tinnitus. By relaxing the lateral pterygoid muscle and interrupting the pain cycle, this renders the condition amenable to long-term control. The practical implications of the described procedure are that it is simple, safe, and well-tolerated with few or no adverse side effects. This novel technique may also be used as a diagnostic feature for the dentist to differentiate between sources of facial pain.

Tinnitus is a condition characterized by the perception of ringing, hissing, or buzzing sounds in or around the ears in the absence of an external sound stimulus.1 It affects millions of individuals worldwide and can range from manifesting with no clinical complaints to highly interfering with daily activities.2 According to Statistics Canada, 37% of Canadians suffered from tinnitus in 2018.3 Approximately 1 in 10 adults in the United States currently have tinnitus.4 Despite its high prevalence, the pathophysiology and cure for tinnitus remain unclear.

Temporomandibular disorders (TMD) are a collective term used to describe musculoskeletal conditions affecting the jaw muscles, temporomandibular joints, and the associated nerves, often causing pain or tenderness in and around the ear, masticatory muscles, and face. The prevalence of TMD-related pain ranges between 5% to 12%,5,6 and the annual incidence is 3.9%.7 Some otologic symptoms frequently associated with TMD include tinnitus, dizziness, vertigo, earache, hyperacusis sensation, ear fullness, hyperacusis, and stuffy sensation.8

A recent study found the incidence of tinnitus to be 11.46% among TMD patients.9 Furthermore, a systematic review evaluating tinnitus among TMD patients has demonstrated a higher prevalence of tinnitus in individuals with TMD compared to the non-TMD population.10

The current management approach to tinnitus includes medications, cognitive behavioural therapy, neuro biofeedback, neuromodulation, tinnitus retraining therapy, sound therapy, and hearing aids.11 Myofunctional therapy used in the management of TMD patients has been found to reduce secondary otalgia, ear fullness, earache, and tinnitus.8,12 In addition, intravenous and trans tympanic administration of 2% Lidocaine was effective in temporarily suppressing tinnitus.13 However, there is no evidence suggesting permanent relief of tinnitus symptoms with intramuscular injection of local anaesthetic agents into the lateral pterygoid muscles.

This case report aims to describe the successful use of an intramuscular injection of 3% Scandonest® plain, a novel technique for tinnitus management in a TMD-related pain patient. The clinical objective was to relax the muscle and break the pain cycle, thereby permitting the subsequent elimination of tinnitus.

Case Report

A 64-year-old female presented to the dental office for an initial TMD consultation and clinical evaluation on the 15th of April 2021. Written, informed consent and ethical approval were obtained from the participant. The patient reported chief complaints of jaw pain, tinnitus, and other symptoms, including ear pain, chewing pain, neck pain, and shoulder pain. A TMD diagnosis was obtained using the Research Diagnostic Criteria or the Diagnostic Criteria (RDC/TMD) for Temporomandibular Disorders.14 Clinical examination revealed a restricted range of jaw motion upon opening and during lateral excursive movements. Facial and cervical muscle palpations revealed pain/inflammation bilaterally. Neck muscles were tender to palpation at the level of C7. Palpation of the temporomandibular joints revealed pain/inflammation bilaterally. The patient reported having her existing dentures for approximately 15 years. The existing complete upper and partial lower dentures were loose and unstable. The only tooth present during the patient’s stomatognathic examination was tooth 44 (Fig. 2).

The patient has responded poorly to standard tinnitus therapy. She had seen an Ear Nose and Throat (ENT) specialist who diagnosed her with tinnitus and ruled out pathology. The patient had undergone a series of hearing tests leading to normal findings. She further reported that tinnitus in her right ear was more prominent than in her left.

The treatment rendered was an intramuscular injection into the lateral pterygoid muscle bilaterally followed by new dentures fabrication with new vertical dimension of occlusion. Three follow-up appointments were made: 1-month in May 2021, 3-months in June 2021 and a 20-months follow-up in December 2022. The diagnosis was established based on the patient’s description of pathognomonic signs, and tinnitus was assessed based on Tinnitus Functional Index (TFI) and Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI)15,16 before and after treatment.

The overall TFI score15 is a 25-item questionnaire that calculates a valid overall TFI score. As a result, the overall TFI score ranges from 0-100, independent of the number of answered questions. The patient scored 80% in auditory difficulties attributed to tinnitus before treatment versus 0% after treatment.

This self-report THI questionnaire16 aims to identify difficulties that the patient may be experiencing because of her tinnitus. THI comprises 25 items with a maximum score of 100, which measures perceived tinnitus handicap severity. Before treatment, the patient scored 44; this represents a moderate (score 38-56) level of tinnitus. This moderate tinnitus score means that tinnitus is perceived even in the presence of environmental sound; however, daily activities are not impaired. Interference with sleep and relaxing activities are not infrequent. In comparison, the patient score post-treatment was 0, out of a maximum score of 100. The patient’s score after treatment being 0 means that tinnitus is no longer present.

Procedure

The intramuscular injection was performed intraorally through the lateral pterygoid muscles bilaterally at the initial consultation appointment. Before the injection, the vestibular surface tissue was cleaned, and a topical anaesthetic was applied (20% benzocaine; Topex®; Sultan Healthcare, York, PA, USA) for two minutes to minimize discomfort. The location of the injection site was accomplished by inserting the needle at a 45-degree angle to the 2nd molar and into the soft tissue region posteriorly located distal to the maxillary tuberosity into the lateral pyrgotid muscles (Fig. 1). A syringe with a 30-gauge needle (Monoject™; Covidien, Dublin, Ireland) was inserted, and a 1.7cc carpule of 3% Scandonest® plain (Mepivacaine Hydrochloride 3% injection, Novocol Pharmaceutical of Canada, Inc., Cambridge, Ontario, Canada, N1R6X3) was injected into the site. The needle was inserted approximately 2 cm into the lateral pterygoid muscle. Before the injection, a negative aspiration was performed, and the anaesthetic was injected.

Fig. 1

Fig. 2

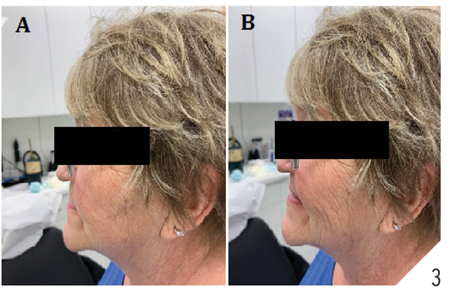

The patient reported that her tinnitus subsided post-injection, but her TMD-related pain persisted. After the injection, new complete upper and lower dentures were fabricated since her existing dentures were ill-fitting and unstable. The vertical dimension of occlusion was increased from 62mm (for her existing dentures) to 66mm (Fig. 3). At the denture delivery appointment, the patient reported that her tinnitus symptoms had vanished, and her pain had subsided. The patient was followed up at 1-month, 3-months, and 20-months from her initial consultation appointment in April 2021. At all three follow-up appointments, the patient reported that her TMD pain (jaw pain, chewing pain), tinnitus, and ear pain was eliminated. To address the patient’s remaining chief complaints of neck pain and shoulder pains, the patient was referred to a physiotherapist at the initial consultation appointment on April 15th, 2021. The physiotherapist performed a total of 7 sessions treating her neck and shoulder pain. The patient has not returned for more physiotherapy sessions since May 14th, 2021.

Fig. 3

Discussion

This case report confirms the finding from previous observational studies that there is a strong association between tinnitus17 and ear pain,18 which results from non-aural pathologies and TMD. The findings of this case report indicate that focal administration of an anaesthetic agent to the lateral pterygoid muscle can relieve tinnitus associated with TMD. The proposed mechanism by which the anaesthetic agent functions is by breaking the pain cycle and relaxing the musculature. Previous clinical studies supported the technique used in this study by Bjorne A. (1993), and it was observed that the tension of the lateral pterygoid muscle could lead to tinnitus in TMD patients. Local intraoral injection of an anaesthetic agent like lidocaine resulted in 20-100% relief of tinnitus.19 In this case study, the anaesthetic agent of choice was 3% mepivacaine without a vasoconstrictor since it is safer to use in dentistry and has a milder vasodilating effect, which leads to a longer duration of anaesthetic in comparison to 2% lidocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine.20

The muscle-relaxing effect of mepivacaine is caused by reducing the uptake of Ca++ by the muscle and competitively inhibiting the contractile action of Ca++ in K+-depolarised muscle.21 Anatomical studies on cadavers have shown that, in some cases, the superior head of the lateral pterygoid muscle can be directly attached to the ear ossicles by means of the retrodiscal tissue and the discomalleolar ligament.22 In addition, the middle and inner ear is innervated by the auriculotemporal branch of the trigeminal nerve, and TMD is also sometimes associated with trigeminal nerve dysfunction.22 Consequently, TMD can manifest with aural symptoms like otalgia, tinnitus and hyperacusis.

A multidisciplinary approach was used to treat TMD-related pain. Studies show that co-morbidities such as neck pain, headache and back pain have been associated with long-term and short-term TMD-related pain.23 Hence, the patient was referred for physiotherapy sessions to address her neck and shoulder pain. The TMD-related pain was treated by adjusting the vertical dimension of occlusion, which is supported by clinical findings by Montieth (1984).24 The patient was diagnosed with myofascial pain with referral, a TMD-related pain diagnosis using the RDC/TMD Criteria, which has high sensitivity (98%) and specificity (86%)25 and uses both clinical examination as well as self-reported questionnaires. To evaluate tinnitus and assess the efficacy of the treatment in reducing tinnitus, standardized tools, namely the TFI and THI with convergent validity (r=.86)12 were used.

A more objective approach to evaluating tinnitus is by audiological testing or an otolaryngologist. However, the patient was not interested in doing that since her symptoms had resolved. Evidence from this case report suggests that the patient had recovered from TMD-related pain and tinnitus after the injection and receiving her new dentures. It is important to note that since tinnitus is multifactorial, it is possible that TMD-related pain may have been a triggering factor for tinnitus. Results suggest that TMD-related symptoms must be treated with a multidisciplinary approach involving other healthcare professionals to address and treat associated co-morbidities. Nonetheless, this novel intramuscular injection may be an adjunct diagnostic procedure for TMD-related pain and tinnitus treatment. Future studies, including population-based and randomized control trials, are required to strengthen the evidence obtained from this case report.

Conclusion

This case report provides evidence that tinnitus associated with TMD can be treated using an intraoral injection of mepivacaine into the lateral pterygoid muscle. Local anaesthesia disrupts the pain cycle and may cause muscle relaxation, thus providing relief to the patient.

Oral Health welcomes this original article.

References

- Langguth, B., T. Kleinjung, and M. Landgrebe, Tinnitus. Evaluation & the Health Professions, 2011. 34(4): p. 429-433.

- F. Pauna, H., M. S.A. Amaral, and M. Â. Hyppolito, Temporomandibular Joint Disorders and Tinnitus. 2019, IntechOpen.

- Pamela L. Ramage-Morin, R.B., Dany Pineault, Maha Atrach, Tinnitus in Canada. Statistics Canada,Health Reports, 2019. 30(March): p. 9.

- Bhatt, J.M., H.W. Lin, and N. Bhattacharyya, Prevalence, Severity, Exposures, and Treatment Patterns of Tinnitus in the United States. JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery, 2016. 142(10): p. 959-965.

- Isong, U., S.A. Gansky, and O. Plesh, Temporomandibular joint and muscle disorder-type pain in U.S. adults: the National Health Interview Survey. J Orofac Pain, 2008. 22(4): p. 317-22.

- Von Korff, M., et al., An epidemiologic comparison of pain complaints. Pain, 1988. 32(2): p. 173-83.

- Slade, G.D., et al., Signs and symptoms of first-onset TMD and sociodemographic predictors of its development: the OPPERA prospective cohort study. J Pain, 2013. 14(12 Suppl): p. T20-32.e1-3.

- Stechman-Neto, J., et al., Effect of temporomandibular disorder therapy on otologic signs and symptoms: a systematic review. Journal of Oral Rehabilitation, 2016. 43(6): p. 468-479.

- Çebi, A.T., Presence of tinnitus and tinnitus-related hearing loss in temporomandibular disorders. CRANIO®, 2020: p. 1-5.

- Mottaghi, A., et al., Is there a higher prevalence of tinnitus in patients with temporomandibular disorders? A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Journal of Oral Rehabilitation, 2019. 46(1): p. 76-86.

- Kim, S.H., et al., Review of Pharmacotherapy for Tinnitus. Healthcare, 2021. 9(6): p. 779.

- Maria De Felício, C., et al., Otologic Symptoms of Temporomandibular Disorder and Effect of Orofacial Myofunctional Therapy. CRANIO®, 2008. 26(2): p. 118-125.

- Savastano, M., Lidocaine intradermal injection—A new approach in tinnitus therapy: Preliminary report. Advances in Therapy, 2004. 21(1): p. 13-20.

- Dworkin, S.F. and L. LeResche, Research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders: review, criteria, examinations and specifications, critique. J Craniomandib Disord, 1992. 6(4): p. 301-55.

- Meikle, M.B., et al., The tinnitus functional index: development of a new clinical measure for chronic, intrusive tinnitus. Ear Hear, 2012. 33(2): p. 153-76.

- Newman, C.W., G.P. Jacobson, and J.B. Spitzer, Development of the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 1996. 122(2): p. 143-8.

- Rubinstein B., Tinnitus and craniomandibular disorders—is there a link? Swed Dent J Suppl, 1993.95: p.1-46.

- Cox KW., Temporomandibular Disorder and New Aural Symptoms. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 2008.134(4): p.389–393.

- Bjorne A., Tinnitus aureum as an effect of increased tension in the lateral pterygoid muscle. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 1993 Sep.109(3 Pt 1):558.

- Su N, et al., Efficacy and safety of mepivacaine compared with lidocaine in local anaesthesia in dentistry: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Int Dent J., 2014 Apr.64(2): p.96-107.

- Aberg G., Andersson R., Studies on mechanical actions of mepivacaine (Carbocaine) and its optically active isomers on isolated smooth muscle: role of Ca ++ and cyclic AMP. Acta Pharmacol Toxicol (Copenh), 1972.31(5): p. 321-36.

- Laersn K., The association between Tinnitus, the Neck and TMJ. MSK Neurology, 2018 Dec.

- Velly A.M., et al., Painful and non-painful comorbidities associated with short- and long-term painful temporomandibular disorders: A cross-sectional study among adolescents from Brazil, Canada and France, Journal of Oral Rehabilitation, 2022 March. 49(3): p. 273- 282.

- Monteith B., The role of the free-way space in the generation of muscle pain among denture-wearers, J Oral Rehabil. 1984.11(5): p.483-498.

- Schiffman E., et al., International RDC/TMD Consortium Network, International association for Dental Research; Orofacial Pain Special Interest Group, International Association for the Study of Pain. Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (DC/TMD) for Clinical and Research Applications: recommendations of the International RDC/TMD Consortium Network and Orofacial Pain Special Interest Group. J Oral Facial Pain Headache. 2014.28(1): p.6-27.

About the Authors

Dr. Sherif Elsaraj graduated from the University of Manitoba with a D.M.D. in 2010. He holds a B.Sc. Honours in Biochemistry, an M.Sc. in Oral Biology, and a Ph.D. in Craniofacial Pain and Health Sciences, and completed 1-year residency training in the Oral and Maxillofacial Radiology program at the UofT. He is an active member of the Canadian Dental Association, Manitoba Dental Association, Ontario Dental Association, and the Order des Dentists du Quebec. Dr. Elsaraj is a Clinical Instructor at McGill University and supervises residents of the General Residency Program, temporomandibular disorders (TMD) & orofacial pain (OFP) Clinic at the Jewish General Hospital Dentistry Department.

Dr. Avinash Sarcar is a Master’s student in Dental Sciences at the Faculty of Dental Medicine and Oral Health Sciences at McGill University. In 2018, he graduated from Rajiv Gandhi University of Health Sciences, Bangalore, India, with a Bachelor’s in Dental Surgery. He worked as a dental practitioner for three years. His interests are chronic pain, sleep disorders and inflammation. He is an active member of the Canadian Pain Society.