Abstract

Orofacial granulomatosis (OFG) is a chronic inflammatory condition with unclear etiopathogenesis that presents with recurrent and/or persistent swelling in the orofacial region. This article describes a case of 14-year-old female with a chief complaint of recurrent swelling of the lips, hyperplastic maxillary anterior gingivae, angular cheilitis, and painful linear ulcerations. The lesion was biopsied, sent for histopathological examination and the microscopic examination revealed non-caseating granulomas. Periodontal therapy resulted in minimal reduction in gingival enlargement and inflammation. A diagnosis of orofacial granulomatosis was assigned by exclusion of systemic conditions. Patient’s lesions resolved within 2-weeks following therapy with topical corticosteroids. An early diagnosis plays a vital role in effective management of these disorders.

Introduction

A variety of local and systemic conditions can cause granulomatous inflammation of the soft tissues in the oral cavity. The term orofacial granulomatosis (OFG) represents swelling and granulomatous inflammation affecting the mucocutaneous tissues of the oral and maxillofacial region without concurrent evidence of systemic condition.1,2 It encompasses a spectrum of conditions with overlapping clinical features representing 0.7% of all mucosal lesions.3 OFG typically presents as recurrent nontender, nonpruritic labial swelling most commonly involving lips.4 However, it can present with highly variable manifestations including hyperplastic gingivitis, persistent deep aphthous like ulcers, angular cheilitis, vertical fissures in the lip, lingual plica (fissuring), a cobblestone appearance of the buccal mucosa and rarely facial nerve palsy.5 The mono-symptomatic form cheilitis granulomatosa (Meischer’s syndrome) presents with exclusive chronic swelling of lips while Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome has recurrent non-pitting edema, fissured tongue and facial paralysis.3,6,7 OFG is naturally heterogenous and its pathophysiology remains unclear. However, a broad array of aetiologies including genetic, immunologic, idiopathic, allergic (dental materials, or food), and infectious processes have been implicated in the causality.8,9 A study reported 48% of the cases exhibit atypical onsets.10 A report also suggested atopic eczema, asthma or hay fever affects 12% to 60% of OFG patients.11 Expansion of monoclonal lymphocytes secondary to chronic antigenic stimulation has also been suggested.12 OFG can occur at any age and shows no predilection for race or sex.13

Histopathologic examination typically reveals non-caseating lymphonodular granulomas, perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with prominent plasma cells, lymphangiectasia, some interstitial infiltrate, edema of superficial lamina propria, and epithelioid histiocytes.8,14,15 Multinucleated giant cells can also be observed around the sarcoid granulomas in some cases.8,15 A variety of systemic conditions can present with clinical and histological similarity such as Crohn’s disease (CD),16 infectious diseases (like tuberculosis,17 leprosy,18 fungi5,18), sarcoidosis, contact lesions, and foreign body reactions.2,8,10,15,19 This clinical and histological similarity between these conditions confounds diagnostic assessment. OFG therefore is considered a diagnosis of exclusion.3,6,9,14

OFG may show spontaneous remissions, but the clinical outcome is unpredictable and delay in management often results in cosmetic defect especially in lips.8,14 Early diagnosis, therefore, plays a key role in preventing significant permanent cosmetic disfigurement. CD has also been reported to develop in 40-50% of the individuals with OFG in childhood.20 Early detection might therefore further aid in diagnosis of the related systemic conditions and slow their progression. Management of these lesions include topical, intralesional and systemic corticosteroid therapy.2,10,19

This article presents a case of OFG in a young female patient which showed favourable response to topical corticosteroid treatment.

Case Report:

A 14-year-old female patient was referred to our office for persistent gingival inflammation in the maxillary anterior region. The patient complained of sore, inflamed maxillary gingivae that were friable and were not healing for the last 6 months. The patient reported gingival bleeding, and difficulty eating food due to pain. The patient informed she recently visited an emergency room with the complain of swelling in the lips that stayed for 2 weeks. The swelling in her upper lip was of a sudden onset and with periods of flareups and remission. The lip swelling subsided, but she continued to have painful ulcers in her mouth as well as angular cheilitis. The gingival overgrowth did not interfere with her ability to chew, or speak but was a cosmetic issue. The patient and her mom confirmed no familial history of similar nature. Her past medical and dental history was non-contributory, and patient denied alcohol, tobacco use or any medications. There was no evidence of any systemic disease. The patient had a history of mild eczematous skin lesions and atopic eczema. She reported no gastrointestinal symptoms. The patient underwent allergy testing that showed allergies to strawberries.

Extraoral examination showed no lymphadenopathy. There was no paralysis of the facial muscles. Intraoral examination showed diffuse erythematous velvety gingival enlargement in the maxillary anterior region spanning entire width of the keratinized gingiva from maxillary left first premolar to maxillary right first premolar. The gingiva was pale pink, soft, edematous with a granular surface generalized loss of stippling and scalloping present for last 6 months. The probing depth on teeth #11, 21, 22 was 5mm with concomitant bleeding on probing and increased mobility. (Figs. 1A & B) Radiographic appearance was within normal limits. The tongue appeared normal however, the patient had a painful linear ulceration on the buccal of tooth #14 and angular cheilitis. Blood chemistry and serological examination for CRP, ESR, antinuclear antibody (ANA) revealed normal results.

Fig. 1

A provisional diagnosis was difficult to establish based on the history and clinical examination. The differential diagnosis included Crohn’s disease, sarcoidosis, angioedema, orofacial granulomatosis, Cheilitis granulomatosa, Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome, Wegener’s granulomatosis, tuberculosis, foreign-body reaction, contact allergy, and fungal infection. Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome was ruled out due to absence of facial paralysis and the tongue appeared normal. Considering the persistence of the lesion, a biopsy was advised after phase I periodontal therapy (oral hygiene instructions (OHI) and scaling, root planing (SRP)).

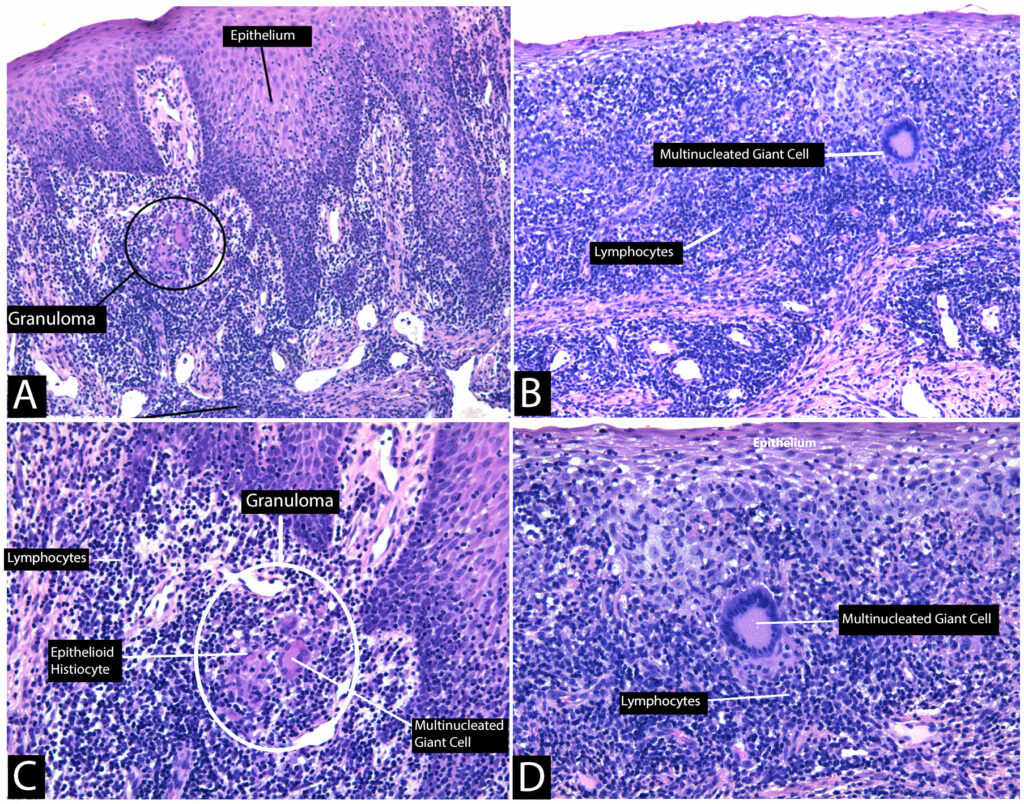

Advantages and disadvantages of the procedure were discussed. An informed consent, both written and verbal, was obtained from the patient prior to commencing the procedure. Following local infiltration anesthesia with 2% Lidocaine having 1:100,000 epinephrine, an incisional biopsy was performed at two different sites. The biopsy specimen measuring 0.7 x 0.3 x 0.1 cm was immediately fixed sin formalin and sent for histopathological examination to the department of oral pathology at the University of Toronto. Microscopic examination of the biopsy sample revealed hyperplastic, parakeratinized stratified squamous epithelium covering fibrous connective tissue. The connective tissue contained patchy dense chronic inflammatory infiltrates comprised of lymphocytes and plasma cells as well as scattered non-necrotizing granulomas consisting of epithelioid histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells. (Fig. 2) According to the biopsy report there was no evidence of foreign material within the granulomas as seen through normal or polarized light examination. Infectious organisms were not identified with GMS (Grocott’s methenamine stain), PASD (Periodic-acid Schiff with diastase), and ZNS (Ziehl-Nielsen) stains ruling out tuberculosis and fungal infection. The differential diagnosis of non-necrotizing granulomatous inflammation included Crohn disease, sarcoidosis, and orofacial granulomatosis.

Fig. 2

Based on history, clinical findings, histopathologic examinations, and laboratory analysis sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, systemic fungal infection, and Crohn’s disease were excluded. The patient was therefore diagnosed with exclusion as orofacial granulomatosis.

Topical corticosteroid therapy with Oracort 0.1% was initiated. The patient tolerated the treatment well and a few weeks later the patient reported significant improvement in her symptoms. (Figs. 1C & D) She indicated relief of pain from oral lesions. The patient was suggested to keep a food diary which revealed patient had swollen gums and lips when she had watermelon, lemonade, strawberries, and starburst candies. The patient was referred to her physician for appropriate referral to ENT and gastroenterologist for further assessment of any systemic condition.

Discussion

OFG initially presents with recurrent and persistent, non-tender swelling of the face or lips characterized by presence of non-caseating granulomas. Its etiology is still unknown but five main causes have been reported in the literature including genetic, immunologic, allergies to food or dental materials and infective causes.8 Atopic eczema has also been reported to affect 12% to 60% of OFG patients.11 Our patient had a history of mild atopic eczema. OFG is a rare condition with broad array of manifestation including painful oral ulcerations, angular cheilitis, lip fissures and hyperplastic gingivitis. These highly variable manifestations make the diagnosis difficult to establish. Early detection and management of these lesions is necessary to prevent esthetic complications.

OFG is diagnosed by an elimination process based on the clinical, histological and laboratory findings. Differential diagnosis included angioedema, Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome, Meischer’s granulomatosis, Wegener’s granulomatosis, sarcoidosis, Crohn’s disease, tuberculosis, fungal infection, foreign-body reaction, and contact allergy. The patient had presented to emergency clinic with sudden edema of the lips. Angioedema does not feature granulomatous inflammation and therefore was excluded from the differential. The lack of facial palsy and fissured tongue helped preclude Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome and more generalized involvement than just lip ruled out Meischer’s granulomatosis. Many of the other granulomatous inflammatory conditions present with similar non-caseating granulomas. OFG is identified from these lesions by appropriate clinical and laboratory investigations confirming absence of systemic conditions.8,15,21,22

The patient was referred to her physician for identification of any systemic involvement. The main signs of Wegener’s granulomatosis are upper respiratory tract involvement with elevated ESR.23 These two contribute to 90% of the signs of Wegener’s granulomatosis.23 Serum analysis for our patient showed no elevation of ESR and the patient presented no evidence of upper respiratory tract involvement. Swelling of the cervical lymph nodes is a classic sign of sarcoidosis.4 Serum angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) is significantly elevated in active sarcoidosis4 and salivary gland is the most affected site intraorally. Lack of swelling in the lymph nodes, salivary glands and laboratory investigations showing normal serum ACE helped rule out sarcoidosis.

Crohn’s disease is an idiopathic, chronic inflammatory bowel disease characterized by granulomatous inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract.3,24 Oral lesions have been reported in 0-20% of Crohn’s disease cases while 0%-37% of individuals with OFG had Crohn’s gut lesions.3,24 Therefore, in children with OFG elevated markers of inflammation, and complete blood count abnormalities CD should also be suspected.13,20 The patient reported no abdominal symptoms and laboratory investigations for C-reactive protein (CRP) & erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) were within due limits. Crohn’s disease was therefore preliminarily ruled out but a referral to gastroenterologist was advised for further assessment.

Microscopic examination under normal and polarized light showed no foreign body cause of granuloma formation. Staining with periodic-acid Schiff (PAS) and Grocott’s methenamine silver (GMS) helps identify presence of deep fungal organisms and Ziehl-Neelsen stain (ZNS) helps detect Acid fast bacilli (AFB). Negative PAS, GMS and ZNS stains ruled out infectious cause of the granulomas in our case.

Elimination diets to identify and exclude certain dietary allergens have been suggested in some studies.10,25 Certain dietary substances like chocolate, cinnamon (common in toothpastes, foods and chewing gum), dentifrice, benzoic acid, monosodium glutamate, and cocoa have been implicated as an initiator of OFG.25-27 We suspected the patient to be allergic to certain foods, additives, toothpaste and therefore was advised to discontinue using dentifrice or mouth rinses and use Nuk baby toothpaste with no additives. She was also referred for allergy testing. She was found to be allergic to watermelon, strawberry, lemonade, and starburst candies that initiated lip swelling. Many foods like fruits, berries and beans contain naturally occurring benzoate that can cause allergies.28 The patient was therefore advised to exclude these from her diet.

She presented with erythematous hypertrophic gingiva spanning from maxillary left first premolar to maxillary right first premolar traversing the width of attached gingiva. The pragmatic approach in localized inflammatory lesions is always phase I periodontal therapy to see the response of the gingival tissue and rule out local pathogenic influence. The patient had poor response to OHI and SRP (phase I periodontal therapy). She also presented with angular cheilitis and painful deep linear ulcers. Following phase I therapy, an incisional biopsy of the lesion was conducted for histopathological examination. Histopathological exam showed non-caseating granulomas with epithelioid histiocytes, lymphocytic infiltration, and multinucleated giant cells confirming orofacial granulomatosis.

Spontaneous remissions of OFG are rare2 and management of symptoms becomes necessary. Corticosteroids have been shown to be effective in reducing the symptoms and prevent recurrences.2,29 A study suggested mild swellings can be managed with topical triamcinolone 0.1% (Oracort) while those with extensive swelling were prescribed systemic medication.2 Since our patient presented with oral ulcerations and mild lip swelling topical corticosteroid (Oracort 0.1%) was prescribed that resolved the lesions.30 Recurrence of the swelling becomes a major concern especially in the lips as they may become indurated and cause permanent cosmetic concern. Cheiloplasty or removal of the lip induration can cause permanent esthetic disfigurement and interfere with eating and speaking.10 Early diagnosis and management of OFG is therefore essential.

Conclusion

OFG remains a diagnostic challenge, delay in the early detection can have serious esthetic and systemic consequences. Repeated labial edema can result in induration that can impair speech and eating. Therefore, early diagnosis and management with appropriate referrals are critical in preventing permanent lip deformation and esthetic impairment. Spontaneous remission is unlikely, and the lesions need continuous monitoring. Management of lesions with corticosteroids remains the mainstay treatment of OFG. Due to variable extent of its manifestation’s different strength and efficacy of topical corticosteroid may be occasionally needed. Crohn’s disease has also been associated with OFG, therefore, appropriate referrals to rule out systemic conditions is necessary. The dentists can thus play a pivotal role in successful management of these cases.

Oral Health welcomes this original article.

References

- Wiesenfeld D, Ferguson MM, Mitchell DN, et al. Oro-facial granulomatosis – a clinical and pathological analysis. Q J Med. 1985;54(213):101-113.

- Sciubba JJ, Said-Al-Naief N. Orofacial granulomatosis: Presentation, pathology and management of 13 cases. J Oral Pathol Med. 2003;32(10):576-585.

- Rees TD. Orofacial granulomatosis and related conditions. Periodontol 2000. 1999;21:145-157.

- Allen R, Mendelsohn FA, Csicsmann J, Weller RF, Hurley TH, Doyle AE. A clinical evaluation of serum angiotensin converting enzyme in sarcoidosis. Aust N Z J Med. 1980;10(5):496-501.

- Troiano G, Dioguardi M, Giannatempo G, et al. Orofacial granulomatosis: Clinical signs of different pathologies. Med Princ Pract. 2015;24(2):117-122.

- Wehl G, Rauchenzauner M. A systematic review of the literature of the three related disease entities cheilitis granulomatosa, orofacial granulomatosis and melkersson–rosenthal syndrome. Curr Pediatr Rev. 2018;14(3):196-203.

- Tilakaratne WM, Freysdottir J, Fortune F. Orofacial granulomatosis: Review on aetiology and pathogenesis. J Oral Pathol Med. 2008;37(4):191-195.

- Grave B, McCullough M, Wiesenfeld D. Orofacial granulomatosis – a 20-year review. Oral Dis. 2009;15(1):46-51.

- Miest R, Bruce A, Rogers RS. Orofacial granulomatosis. Clin Dermatol. 2016;34(4):505-513.

- Mignogna MD, Fedele S, Lo Russo L, Lo Muzio L. The multiform and variable patterns of onset of orofacial granulomatosis. J Oral Pathol Med. 2003;32(4):200-205.

- Armstrong DK, Biagioni P, Lamey PJ, Burrows D. Contact hypersensitivity in patients with orofacial granulomatosis. Am J Contact Dermat. 1997;8(1):35-38.

- Lim SH, Stephens P, Cao QX, Coleman S, Thomas DW. Molecular analysis of T cell receptor beta variability in a patient with orofacial granulomatosis. Gut. 1997;40(5):683-686.

- Gavioli CFB, Florezi GP, Dabronzo MLD, Jiménez MR, Nico MMS, Lourenço SV. Orofacial granulomatosis and crohn disease: Coincidence or pattern? A systematic review. Dermatology. 2021;237(4):635-640.

- Brown R, Farquharson A, Cherry-Peppers G, Lawrence L, Grant-Mills D. A case of cheilitis granulomatosa/orofacial granulomatosis. Clin Cosmet Investig Dent. 2020;12:219-224.

- Marcoval J, Penín RM. Histopathological features of orofacial granulomatosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2016;38(3):194-200.

- Crohn BB, Ginzburg L, Oppenheimer GD. Regional ileitis: A pathologic and clinical entity. 1932. Mt Sinai J Med. 2000;67(3): 263-268.

- SHENGOLD MA, SHEINGOLD H. Oral tuberculosis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1951;4(2):239-250.

- Alawi F. Granulomatous diseases of the oral tissues: Differential diagnosis and update. Dent Clin North Am. 2005;49(1):203-21, x.

- Troiano G, Dioguardi M, Giannatempo G, et al. Orofacial granulomatosis: Clinical signs of different pathologies. Med Princ Pract. 2015;24(2):117-122.

- Lazzerini M, Bramuzzo M, Ventura A. Association between orofacial granulomatosis and crohn’s disease in children: Systematic review. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(23):7497-7504.

- Leão JC, Hodgson T, Scully C, Porter S. Review article: Orofacial granulomatosis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20(10):1019-1027.

- Singhal P, Chandan GD, Das UM, Singhal A. A rare case report of orofacial granulomatosis in a pediatric patient. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2012;30(3):262-266.

- Bachmeyer C, Petitjean B, Testart F, Richecoeur J, Ammouri W, Blum L. Lingual necrosis as the presenting sign of wegener’s granulomatosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;31(2):321-322.

- . Matricon J, Barnich N, Ardid D. Immunopathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Self Nonself. 2010;1(4):299-309.

- Reed BE, Barrett AP, Katelaris C, Bilous M. Orofacial sensitivity reactions and the role of dietary components. case reports. Aust Dent J. 1993;38(4):287-291.

- White A, Nunes C, Escudier M, et al. Improvement in orofacial granulomatosis on a cinnamon- and benzoate-free diet. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12(6):508-514.

- Taibjee SM, Prais L, Foulds IS. Orofacial granulomatosis worsened by chocolate: Results of patch testing to ingredients of cadbury’s chocolate. Br J Dermatol. 2004;150(3):595-2133.2004.05829.x.

- Marttala A, Sihvonen E, Kantola S, Ylöstalo P, Tervonen T. Diagnosis and treatment of orofacial granulomatosis. J Dent Child (Chic). 2018;85(2):83-87.

- Allen CM, Camisa C, Hamzeh S, Stephens L. Cheilitis granulomatosa: Report of six cases and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23(3 Pt 1):444-450.

- van der Waal, R I, Schulten EA, van der Meij, E H, van de Scheur, M R, Starink TM, van der Waal I. Cheilitis granulomatosa: Overview of 13 patients with long-term follow-up–results of management. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41(4):225-229.

About the Authors

Dr. Sandeep Dab is a board-certified periodontist in Midtown Toronto who provides the full scope of surgical periodontal and dental implant procedures. He can be reached at info@davisvilleperiodontics.com Davisville Periodontics, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Justin Bubola is an Assistant Professor in Oral Pathology and Oral Medicine at the Faculty of Dentistry, University of Toronto.

RELATED ARTICLE: Orofacial Pain (OFP): The Light at the End of the Tunnel