Introduction

In 1964 Bob Dylan shared his famous observation, “The Times They Are A-Changin’.” Those words seem to continue to ring true in every facet of life today. Evolving materials and technologies offer cosmetic dentists and ceramists new tools to meet patient demands for quality esthetic dentistry. Esthetically driven dental consumers are often exacting and extremely demanding with regard to their expected treatment results. While clear communication between the patient, the dentist, and the ceramist coupled with meticulous planning and precise execution of the plan continues to serve as the foundation for esthetic and functional success, the development of new products and protocols offers different pathways for achieving exceptional results with porcelain veneers.

Case Study

Diagnosis

An 18-year-old female in excellent medical and dental health presented stating she maintains annual dental cleanings and has whitened her teeth in the past. The patient was unhappy with the general shape, positioning, and shade of her teeth. She was particularly concerned with the improper proportions in width-to-length ratios of her incisors and the diastemata present (Fig 1).1 Several areas of gingival asymmetry were also noted. She expressed her desire to have a beautiful, “natural” smile without pursuing orthodontic options.

Fig. 1

A full mouth series of periapical radiographs was made, and no pathology was noted. Clinical examination revealed a Class I dental relationship with no significant occlusal interferences. Evidence of mild wear was found on the patient’s anterior teeth, however, the patient exhibited no symptoms of any temporomandibular disorder and appeared asymptomatic during a TMJ evaluation.2

Treatment Plan

Following discussion of esthetic restorative options for her smile, the patient elected to pursue treatment of teeth #6, 7, 8, 9, 10, and 11 with minimal preparation porcelain veneers. The patient stressed that a natural, conservative, long-lasting result was her primary goal. Proper care for the future porcelain restorations was discussed including nightly wear of a hard-protective occlusal guard, and the importance of optimal maintenance including regular cleanings and examinations was stressed.3

A comprehensive set of records was made of the patient’s preoperative condition including a detailed lab prescription to allow for proper communication between the dentist and the ceramist. Honigum Pro (DMG America; Englewood, NJ) polyvinyl siloxane impressions were made of both arches, and study models were fabricated in die stone.3,4,5,6 Occlusion was recorded with a Futar D (Kettenbach; Eschenburg, Germany) polyvinyl siloxane bite registration and a facebow transfer. Digital photographs documenting the preoperative shade, texture, and shape of surrounding teeth were made.3,4,6,7 All records were sent to the lab where the study models were mounted on a semi-adjustable articulator, and teeth #6, 7, 8, 9, 10, and 11 were waxed to full contour. A Sil-Tech (Ivoclar Vivadent; Amherst, NY) polyvinyl siloxane stent was then formed to fabricate an incisal reduction matrix.

Description of Treatment

The patient was able to view and approve the diagnostic wax up presented on mounted study models prior to any preparation of her teeth.3,4 Under color corrected lighting, digital photographs were made from multiple angles with at least two shade tabs per photograph to assist in shade matching and color mapping (hue, chroma, and value) prior to any dehydration of the teeth.3,4 A shade map was also produced by the dentist to be used as a complimentary guide for the ceramist.

Profound anesthesia of #6-11 was obtained through the use of Kovanaze tetracaine HCL and oxymetazoline HCl nasal spray (St. Renatus; Fort Collins, CO) followed by application of a topical anesthetic to areas indicated for tissue recontouring (Fig 2). Due to the profound effectiveness of the nasal anesthetic, traditional intraoral injections were unnecessary. The patient’s lips were adequately and comfortably retracted for the entire procedure using an Optragate lip retractor (Ivoclar Vivadent; Amherst, NY). Tissue sculpting was performed with a Gemini Diode laser (Ultradent Corp; West Jordan, UT) to even gingival levels on teeth #7, 8, and 11 (Fig 3). Careful attention was paid in measuring tissue to be removed coupled with preoperative bone sounding to avoid invasion of biologic width.3,4,5,6,8

Fig. 2

Fig. 3

Fig. 4

Initial tooth preparation was completed with a 2000.10 Two Striper super-coarse grit diamond bur (Premier Dental; Plymouth Meeting, PA) in a high-speed handpiece under copious water spray (Fig. 4). Due to the diastemata and positioning of the patient’s teeth, minimal tooth reduction of the patient’s enamel was required. Adequate incisal (1.5 mm) and facial (.75 mm) porcelain thickness needed to provide room for layering, slight color change, and addition of incisal effects in the porcelain was confirmed with the lingual and incisal polyvinyl siloxane stent.3,4 A well-defined cervical margin was established with a 703.8F diamond bur (Premier Dental; Plymouth Meeting, PA) to provide a positive veneer stop with a smooth, cleansable, precise porcelain to tooth interface while allowing for development of proper emergence profile.3,4 Abrasive discs (Cosmedent Inc.; Chicago, IL) in a slow speed handpiece were used to eliminate any sharp angles that could provide for internal stress points.3,4 Photographs of the preparations were made and a preparation shade of st9 (Ivoclar Vivadent; Amherst, NY) was recorded. Expa-syl gingival retraction paste (Acteon Group; Mèrignac, France) was expressed around all gingival margins to provide hemostasis and adequate tissue reflection. After three minutes, the paste was rinsed away with a copious, forceful water spray. The preparations were dried and a master polyvinyl impression was made with Honigum Pro Light and Heavy impression material (DMG America; Englewood, NJ) (Fig. 5). A Futar D (Kettenbach; Eschenburg, Germany) stick bite of the prepared teeth in centric occlusion was made and photographed.

Fig. 5

The patient’s teeth were cleaned with Consepsis chlorhexidine (Ultradent Corp; West Jordan UT). A polyvinyl siloxane stent made from the diagnostic waxup was filled with BL Luxatemp Ultra (DMG America; Englewood, NJ) and placed over the prepared teeth and allowed to cure. After approximately one minute, the stent was gently removed with the veneer provisionals remaining inside. The provisionals were removed from the stent, trimmed, and then seated with Optibond FL resin (Kerr Corp; Orange, CA). They were tack cured for five seconds on each tooth with the Bluephase LED curing light (Ivoclar Vivadent; Amherst, NY). Excess material was removed with a #12 scalpel blade, an additional 15 second curing time per tooth was completed, and the provisionals were smoothed and finished with abrasive discs (Cosmedent Inc.; Chicago, IL) and a rubber cup polisher (Cosmedent Inc.; Chicago, IL). Occlusion was verified and checked and the patient was appointed for a post-operative check twenty-four hours later.

The 24-hour post-operative check appointment was particularly important because it allowed the patient to express feedback based on self-analysis of the proposed shapes and contours of her new smile. The patient reviewed and approved the shape of her provisional restorations and the shade tabs selected at the prior appointment. Proper phonetics, occlusion, and anterior guidance were confirmed. Photographs of the approved provisional restorations and shade tabs were made. Other provisional records were made including a Futar D stick bite (Kettenbach; Eschenburg, Germany) in centric occlusion and a Honigum Pro polyvinyl impression (DMG America; Englewood, NJ) of the approved provisionals. All records were disinfected and sent to the ceramist accompanied by a completed laboratory prescription and all photographs taken to this point. The ceramist was instructed to use the impression of the approved provisionals as a guide for the final shape, size, and contour of the porcelain restorations.

Laboratory Phase

During the provisional phase the patient was able to further reevaluate the provisional restorations. If she had requested any changes, they could have been communicated to the ceramist during this period. No changes were requested during this time. On the ceramist’s receipt of the case, the records were reviewed and the material choice on the prescription was confirmed during a telephone conversation. Shape, shade, and characterization were discussed again and finalized in the planning stage. Producing the patient’s desired shade choice dictated e.Max MTBL2 blocks (Ivoclar Vivadent; Amherst, NY) to be milled as a base shade. Cutback and layering of the milled veneers was planned to develop restorations with the requested moderate incisal character and natural gingival staining with a lightly textured, polished gloss finish.

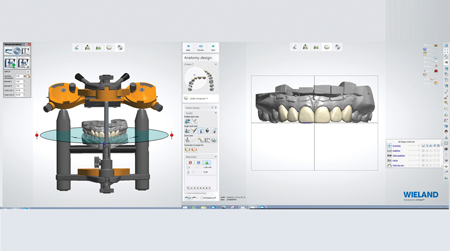

The ceramist utilized a 3Shape D1000 scanner (Ivoclar Vivadent; Amherst, NY) to digitize the physical models. The digital provisional record was then stitched with the master die model to serve as a template for digital design (Fig. 6). The ceramist was able to easily adjust and refine shapes and contours to produce a digital design precisely matching the patient’s expectations as communicated by the dentist (Fig. 7). The digital design was then separated into individual veneers. Each veneer was milled as a separate unit utilizing a Weiland Zenotec Select Hybrid milling unit (Ivoclar Vivadent; Amherst, NY).

Fig. 6

Fig. 7

Marginal accuracy of the full contour milled veneers was then confirmed on the physical die models. Cutback of each full contour milled unit was performed as needed to allow for hand layering of IPS e.Max Ceram porcelain (Ivoclar Vivadent; Amherst, NY) to develop realistic translucency, depth, and character (Fig. 8). Following layering and firing, each unit was hand finished and polished. The ceramist meticulously confirmed fit and esthetics for the entire case (Fig. 9). The intaglio of each unit was lightly sandblasted and then acid etched for one-minute with 9.5% HCl (Keystone Industries; Gibbstown, NJ). The veneers were then steam cleaned and carefully packaged for return to the dentist ready for the seat appointment.

Fig. 8

Fig. 9

Cementation

On return from the ceramist, the porcelain restorations were inspected on the dies for marginal fit and on solid models for proper interproximal contacts. Profound anesthesia was obtained through the use Kovanaze nasal spray anesthetic (St. Renatus; Fort Collins, CO) to avoid discomfort from injections and allow the patient to maintain control of her lip during and after the seat appointment. An Optragate lip retractor (Ivoclar Vivadent; Amherst, NY) was placed to assist in isolation. The provisional veneers were removed, and the preparations were cleaned to remove any residual resin temporary material or debris. The veneers were then tried into the patient’s mouth and evaluated for fit and esthetics (first individually, then collectively) (Fig. 10). The patient was then allowed to view and approve the esthetics of her smile in a hand mirror.

Fig. 10

The approved veneers were removed from the patient’s mouth and carefully cleaned with Ivoclean cleaning paste (Ivoclar Vivadent; Amherst, NY) to remove any possible contamination. They were rinsed, dried, and Monobond silane coupling agent (Ivoclar Vivadent; Amherst, NY) was applied to the intaglio of the veneers.9 Following one minute they were air dried, and a thin coating of All Bond Universal bonding agent (Bisco; Schaumberg, IL) was applied to the inside of the veneers and air thinned. Vitique Clear Veneer Cement (DMG America; Englewood, NJ) was then applied to the veneers and they were immediately placed into a ResinKeeper light-safe box (Cosmedent Inc.; Chicago, IL) to prevent polymerization of the resin.3,4

The preparations were acid etched for 15 seconds with 35% UltraEtch phosphoric acid gel etchant (Ultradent Corp; West Jordan, UT) followed by rinsing with a copious air and water spray.3,4 All preparations were lightly dried, but not dessicated.3,4 Two coats of All Bond Universal bonding agent (Bisco; Schaumberg, IL) were applied to each preparation and agitated for 20 seconds prior to air thinning to evaporate solvents. Each tooth was cured for 20 seconds with a Bluephase LED curing light (Ivoclar Vivadent; Amherst, NY). The veneers were then removed from the light-safe box and seated on their respective preparations. Excess cement was removed with a Regular Microbrush (Microbrush International; Grafton, WI) and they were tacked into place for 5 seconds each with the curing light.10 Additional excess was removed gently with a scaler, floss was passed through the contacts in the apical direction only, and the veneers were then cured fully for an additional 30 seconds each.10 The margins were then inspected and any excess cured cement was removed with a #12 scalpel blade.10 Interproximal areas were cleaned with Epitex finishing strips (GC America; Alsip, IL). DeOx oxygen inhibiting gel (Ultradent Corp; West Jordan, UT) was expressed around all margins and the restorations were cured an additional 10 seconds to finalize polymerization.3,4,9 The lingual aspect was then polished with diamond paste and Flexibuff polishers (Cosmedent Inc.; Chicago, IL) in a slow speed handpiece and isolation was removed.

The patient’s occlusion was checked and smooth, proper contacts were verified with dental floss. Post-operative home care instructions were given and the patient was scheduled for a follow-up appointment for radiographic and photographic documentation as well as a follow-up check for function and esthetic evaluation.

The patient returned the following day. Her functional occlusion was evaluated, and her teeth were inspected for any residual cement. Maxillary and mandibular alginate impressions were made along with a polyvinyl siloxane bite registration for fabrication of a maxillary full arch bite guard for nighttime wear.3 Post-operative home care instructions were given and the patient was scheduled for a follow-up appointment for radiographic and photographic documentation, a final check for function and esthetic evaluation, and delivery of the patient’s maxillary protective bite guard (Figs. 11 & 12).3

Fig. 11

Fig. 12

Conclusion

Porcelain veneers can be employed to provide beautiful, natural, and long-lasting functional cosmetic results. Careful planning, great communication, and meticulous use of

contemporary dental techniques and materials yielded an excellent result that surpassed the patient’s expectations (Fig. 13).

Fig. 13

Oral Health welcomes this original article.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to express sincere appreciation to Wayne B. Payne, MDT, AAACD and Tyler Payne for their technical expertise and beautiful porcelain work.

References

- American Academy of Cosmetic Dentistry. Diagnosis and Treatment Evaluation in Cosmetic Dentistry: A Guide to Accreditation Criteria. Madison (WI): The Academy; 2001.

- Dawson, Peter E. Evaluation, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Occlusal Problems. The C.V. Mosby Co.: St Louis, MO; 1989.

- Magne, Pascal. Bonded Porcelain Restorations in the Anterior Dentition A Biomimetic Approach. Quintessence Books: Chicago, IL; 2002.

- Gurel, Galip. The Science and Art of Porcelain Laminate Veneers. Quintessence Books: Chicago, IL; 2003.

- Rufenacht CR. Fundamentals of Esthetics. Quintessence Books: Chicago, IL; 1992.

- Fradeani, Mauro. Esthetic Analysis A Systematic Approach to Prosthetic Treatment Volume 1. Quintessence Books: Chicago, IL; 2004.

- Goldstein, Ronald E. Esthetics In Dentistry. B.C. Decker, Inc.: Hamilton, Ontario; 1998.

- Flax, Hugh. Smile Enhancement With Laser Technology- Predictable and Esthetic: A Case Report. The Journal of Cosmetic Dentistry. 23(1): 92-98, 2007.

- Touati B, Quintas AF. Aesthetic and Adhesive Cementation for Contemporary Porcelain Crowns. Practical Procedures in Aesthetic Dentistry. 13(8): 611-620, 2001.

- Miller, Michael B. Reality: The Techniques: Volume I. Reality Publishing Co.: Houston, TX; 2003.

About The Author

W. Johnston Rowe, Jr. D.D.S., A.A.A.C.D. maintains a private practice dedicated to general, cosmetic, and complex restorative dentistry in Jonesboro, Arkansas. He is an Accredited Member of the American Academy of Cosmetic Dentistry, past member and Chairman of the American Board of Cosmetic Dentistry, and has served as the AACD’s Chairman of Accreditation. He also serves as an Accreditation Examiner for the AACD. Dr. Rowe has been awarded Fellowships in the International College of Dentists and the Pierre Fauchard Academy. He is a graduate of the University of Tennessee College of Dentistry, and is a formally trained artist with a Bachelor of Arts degree in Studio Art. Dr. Rowe enjoys lecturing nationally and internationally, and can be contacted at info@rowesmiles.com or 870.932.4126.

W. Johnston Rowe, Jr. D.D.S., A.A.A.C.D. maintains a private practice dedicated to general, cosmetic, and complex restorative dentistry in Jonesboro, Arkansas. He is an Accredited Member of the American Academy of Cosmetic Dentistry, past member and Chairman of the American Board of Cosmetic Dentistry, and has served as the AACD’s Chairman of Accreditation. He also serves as an Accreditation Examiner for the AACD. Dr. Rowe has been awarded Fellowships in the International College of Dentists and the Pierre Fauchard Academy. He is a graduate of the University of Tennessee College of Dentistry, and is a formally trained artist with a Bachelor of Arts degree in Studio Art. Dr. Rowe enjoys lecturing nationally and internationally, and can be contacted at info@rowesmiles.com or 870.932.4126.

RELATED ARTICLE: The Endodontic Restorative Harmonic: Part I Access To Apex, Apex To Access