Introduction

Orthodontic and periodontal therapy are intimately connected. To ensure a functional and aesthetically pleasing outcome the process begins with clinical assessment of many factors including periodontal probing depths, thickness of the attached gingiva, mobility, occlusion, furcation involvement and bleeding. This will ensure there are no underlying issues that could become aggravated by tooth movements.1,2 For simplicity and brevity’s sake of the article, I will assume active periodontal disease has been eliminated and/or controlled and the remaining challenge is to ensure that the amount of overlying osseous and gingival tissue is optimized. An important determining factor whether grafting is required, is the horizontal position of the root relative to the surrounding alveolus.3 Digital palpation may give an indication of relative root prominence. Radiographically, conventional two-dimensional imaging modalities (peri-apical, bitewing, orthopantogram) are limited to depicting the mesial-distal and apico-coronal view. Specifically, the crestal bone level and the distance from the crest to the contact point are especially important in predicting the amount of achievable root coverage4,5 and papillae fill6 respectively, subjects for another time. Three-dimensional cone beam computed tomography offers the advantage of elucidating the horizontal buccal-palatal/lingual prominence. If grafting is indicated, the next queries become when and how. Should grafting be performed prior, during or after orthodontic therapy? And, should it be in the form of gingival, osseous or both? The presenting attachment level, anticipated orthodontic vector and the degree to which the root is within the alveolar housing will influence the answers.

The further within the alveolus the root is, the less likely augmentation will become necessary. As the root is further displaced out of the housing it is more likely intervention will be required. The least invasive scenario would be one where orthodontic movement alone improves the deficit. It is known that vectors away from a recessional defect may lead to an improvement in the amount of attached gingiva7 while vectors towards will result in further attachment loss.8

If the anatomic scenario is such where the root is (and will remain) predominantly within the alveolus and periodontal surgery becomes indicated at any point during orthodontic therapy, typically soft tissue augmentation will suffice. The graft will help support the remaining tissue, improve resilience and potentially achieve coverage of exposed root surfaces (see Case Reports 1, 2, 6).

If the root is (or will be) predominantly outside of the alveolar confines and surgery is indicated, either hard, soft or a combination of tissues will be required. In this scenario the limitations of certain surgical modalities may eliminate it as an option thus clarifying the better approach (see Case Reports 3, 4 and 5).

A potpourri of such interventions and their circumstances will be the focus of the remainder of this article.

Case Report 1: Intra-orthodontic lingual connective tissue graft

A 31-year-old healthy male (ASA 1) presented with history of orthodontic therapy and an advancing 8mm lingual recession at tooth 31 with minimally attached gingiva (MAG). The incisal edge of 31 was tipped facial with the root lingually protruding out of the alveolus. A periapical confirmed minor horizontal crestal bone loss. A CBCT was not needed to diagnose and treatment plan. (Figs. 1A-C)

Fig. 1A

Fig. 1B

Fig. 1C

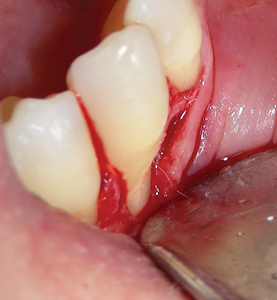

Orthodontics were initiated to bring the root back into the alveolus with spontaneous 50% defect resolution and alignment of the incisal edges. (Figs. 1D,E) To complement the orthodontic mediated improvement a connective tissue graft was planned. Intra-surgical lingual plate dehiscence was noted at both the 31 and 32 and minor mechanical root reduction was necessary to further reduce the remaining root prominence. (Fig. 1F) This created sufficient room for a (palatal) autogenous sub-epithelial connective tissue graft to fit passively and allow for tension free primary closure with 5-0 chromic gut interrupted and sling sutures. (Figs. 1G-J) A key to optimal healing is avoiding post-surgical trauma which could lead to severing of the anastomosing vessels and subsequent necrosis and sloughing of the graft. A clear plastic guard was prefabricated to protect the site from any such forces. (Fig. 1K) Eight week post-surgical examination demonstrated adequate healing at both the donor and recipient sites. (Figs. 1L,M) Such an outcome would have been impossible without preliminary corrective orthodontic movements.

Fig. 1D

Fig. 1E

Fig. 1F

Fig. 1G

Fig. 1H

Fig. 1I

Fig. 1J

Fig. 1K

Fig. 1L

Fig. 1M

Case Report 2: Post-orthodontic facial connective tissue graft

A 65-year-old female (ASA 2 – Rx controlled psoriatic arthritis) presented with symptomatic 5mm facial recession with MAG at 43. Similar to the previous case, it was determined that orthodontic movement was a necessary pre-requisite to rehabilitation as the facially displaced tooth (and root) was clearly not within the alveolus. A peri-apical film confirmed healthy interproximal bone height and the chance for predictable root coverage. (Figs. 2A-C) After completing 18 months of therapy, the patient returned with a well aligned arch and improved tooth (and root) position. (Figs. 2D,E) In anticipation of a coronally displaced flap, a minor epithelial discard was taken at the mesial and distal leaving the connective tissue bed intact. (Fig. 2F) A split thickness flap to the mucogingival junction and a full thickness thereafter exposed the residual denuded root surface. Minor mechanical reduction was again necessary to provide space for a (palatal) autogenous sub-epithelial connective tissue graft. (Figs. 2G-I) Tetracycline (50mg/mL) was used to chemically prepare the root for graft placement and subsequent tension free coronal flap closure achieved. (Figs. 2J-L) Three-month follow-up demonstrated good root coverage with thick tissue and maintenance of the interdental papillae. (Fig. 2M) Again, orthodontic therapy facilitated periodontal surgery.

Fig. 2A

Fig. 2B

Fig. 2C

Fig. 2D

Fig. 2E

Fig. 2F

Fig. 2G

Fig. 2H

Fig. 2I

Fig. 2J

Fig. 2K

Fig. 2L

Fig. 2M

Case report 3: Post-orthodontic facial guided bone augmentation

A 29-year-old female (ASA 1) presented with 5mm facial recession at 31 with MAG, obvious marginal edema and erythema. Despite a healthy band of facial attached gingiva at 41, the root palpated somewhat prominently more apical. This raised concern for collateral surgical damage to the 41 if it were not factored into the plan and treated prophylactically during the procedure. As the incisal edges were well aligned, further orthodontics would have needed to translate the tooth bodily to the lingual. (Figs. 3A,B) To determine the appropriate approach a CBCT was ordered. The panoramic view demonstrated evenly spaced roots without crowding and minor horizontal bone loss suggesting the possibility of post-surgical residual gingival recession. The cross-sectional slices highlighted the buccal-lingual thinness of the alveolar ridge and prominence of the 90% exposed, extra-osseous facial root surface. Measurement of the interproximal “valley” depth on the axial slice was 2.5mm. A key subtlety of the axial view is appreciating the facial position of the root canals of the incisors relative to the facial cortex of the interproximal bone. Mechanical reduction of the root surface to provide space for a tissue graft would have resulted in perforation. Analysis of the various dimensions and the 3-D reconstruction clearly indicated a hard-tissue graft was the correct technique and contraindicated a soft-tissue graft. (Fig. 3C) A full-thickness flap was elevated confirming all that was gleaned from the CBCT and bone grafting was performed. (Fig. 3D) Periosteal release to facilitate coronal flap repositioning and inter-radicular corticotomies were made to encourage vascular supply to the graft material. (Fig. 3E) Mineralized cortico-cancellous freeze-dried bone allograft (FDBA) was resuspended in saline with amoxicillin and generously applied to achieve root coverage from 32-42. The graft was contained by a bovine collagen membrane and tension free primary closure of the flap secured with interrupted, interproximal 4-0 PTFE suture. Two interrupted 5-0 chromic gut sutures were placed at the facial of 31 to avoid premature membrane exposure. (Figs. 3F,G) Fifteen month post-surgical examination showed slight loss of papilla height, minor gingival recession with dramatically improved tissue coverage at 31 and generally improved alveolar thickness. (Figs. 3H,I) As the patient was clinically stable, asymptomatic and happy with the aesthetics, no adjunctive soft-tissue grafting was required. A combination of factors on a genetically susceptible host resulted in the initial periodontal defect. Orthodontic therapy alone was not sufficient to remedy the issue and required the correct selection of a complementary surgical therapy to be rectified.

Fig. 3A

Fig. 3B

Fig. 3C

Fig. 3D

Fig. 3E

Fig. 3F

Fig. 3G

Fig. 3H

Fig. 3I

Case report 4: Intra-orthodontic Periodontally Accelerated Osteo-genic Orthodontics (PAOO)9,10

A 40-year-old male (ASA 2 – Rx controlled hypertension and ADHD) presented to the orthodontist for correction of his malocclusion. After discussion it was decided to pursue PAOO with the objective of a shorter treatment time. This process combines alveolar decortication and augmentation techniques with orthodontic mechanics. Through regional accelerated phenomenon (RAP)11, a transient burst of increased healing capacity occurs during the remodeling process in response to cortical injury. The addition of the bone graft allows for acceleration of orthodontic movements in an alveolus that is otherwise not of an ideal shape or size without compromising the overlying hard and soft-tissue. Baseline photos show bilateral posterior crossbite, anterior crowding and a constricted palate. (Figs. 4A-E) A CBCT was ordered to reveal any underlying defects (note 16 palatal root exposure), anatomical features (maxillary sinuses, foramina, root locations) and plan precise corticotomies. (Fig. 4F) Under IV-conscious sedation, the radiographic information was translated intra-orally via graphite markings. (Fig. 4G) Buccal and palatal corticotomies were performed with a high speed handpiece and thin cross-cut fissure bur following the delineations (buccal quadrant 1 shown for brevity). (Fig. 4H) A combination of demineralized and mineralized cortico-cancellous FDBA was resuspended in saline and generously applied over both buccal and palatal corticomies. (Fig. 4I) The graft was contained beneath a bovine collagen membrane and tension free primary closure of the flap secured with interproximal 4-0 PTFE suture. Increased buccal and palatal ridge thickness relative to baseline was readily apparent. (Figs. 4J,K) Final photographs demonstrate satisfactory orthodontic and periodontal outcomes from both patient and professional perspectives. (Figs. 4L-P)

Fig. 4A

Fig. 4B

Fig. 4C

Fig. 4D

Fig. 4E

Fig. 4F

Fig. 4G

Fig. 4H

Fig. 4I

Fig. 4J

Fig. 4K

Fig. 4L

Fig. 4M

Fig. 4N

Fig. 4O

Fig. 4P

Case report 5: Intra-orthodontic facial free-gingival graft

A 13-year-old girl (ASA 1) presented during the course of her orthodontic therapy with 5mm facial recession at both 31 and 41 with MAG and marked marginal edema and erythema. (Fig. 5A) It is my strong preference to avoid surgical intervention in children and adolescents as long as possible for several reasons. In addition to the active and passive eruption phases that are occurring in the mixed dentition, research has shown that the amount of attached gingiva changes over time as well.12 Foremost, I want to avoid the trepidation and anxiety associated with surgery as such a young age. In this circumstance, attachment loss was progressive and intervention was necessary. As orthodontic therapy was coming to a finish and the roots were predominantly within the alveolus, their prominence was not an issue. It was decided to treat via soft-tissue augmentation. Due to the thin biotype, I was concerned for intra and post-surgical flap dehiscence/fenestration. As root coverage was desired, a phased approach was planned beginning with free-gingival grafting to predictably increase the zone of attached gingiva and arrest the attachment loss. To achieve root coverage, connective tissue grafting would follow and would now occur in a more favourable surgical environment. A peri-apical film confirmed minor horizontal bone loss and an elongated vertical distance between the crest and the contact point, both associated with expected gingival recession in the near term and incomplete root coverage in the future. (Fig. 5B) A split-thickness incision was made at the mucogingival junction, a graft harvested from the hard palate and fixed with a combination of interrupted and mattress chromic gut sutures. (Figs. 5C-E) At three weeks post-operative, graft adaption and palatal healing were well underway. (Figs. 5F,G) Subsequently, the teenager grew up and interest in root coverage waned as the teeth were now stabilized. Until seven years later she reappeared for consultation for root coverage but not for the mandibular anterior but rather the maxillary canines. As was expected, between passive eruption, time and biotype, recession was noted. The free-gingival graft was readily apparent and well-integrated. Most importantly the periodontium was predominantly stable with only minor erythema and a rolled margin at the 32 facial. (Fig. 5H) Interestingly, 4 years has since passed and I have not seen the patient. Perhaps this case will be concluded in a future article.

Fig. 5A

Fig. 5B

Fig. 5C

Fig. 5D

Fig. 5E

Fig. 5F

Fig. 5G

Fig. 5H

Case report 6: Post-orthodontic facial free-gingival graft

The early detection and diligent follow-through of this multi-year ortho-perio case allowed us to optimize the timing of the surgical therapy. Through conservative management we avoided an operation prior to initiating orthodontics. We also avoided a more complicated technical and logistical surgery during orthodontic therapy which would have entailed working around orthodontic hardware and coordination of removal and replacement of the archwire. By emphasizing oral hygiene and homecare instructions to a receptive and motivated patient and mother, we were able to limit the periodontal damage over the course of therapy. The patient first presented at age 12 with a referral to address “severe recession” prior to initiating tooth movements. Upon clinical exam there was indeed 1mm of recession at the 41 facial that was accentuated by the gingival coverage at the 32 and 42. Generalized marginal edema and plaque accumulation was also noted. (Fig. 6A) After specific hygiene instructions the patient returned for re-evaluation four months later demonstrating improved tissue tone, less plaque and minor advancement of the 41 recession. This was likely secondary to resolution of edema rather than bona fide attachment loss. (Fig. 6B) Orthodontics was commenced and the patient was seen for assessment. Plaque accumulation was apparent and had likely led to advancing recession at 41 and increased edema of the marginal tissue. (Fig. 6C) Hygiene was reviewed and again the tissues responded favorably with reduced plaque and edema evidenced by increased tooth display. (Fig. 6D) Upon completion of orthodontic therapy I re-evaluated her periodontium, noting a minor concern at the 41 facial. I once again opted for a conservative approach by re-emphasizing hygiene in the hopes of improving the tissue tone and continuing to avoid surgery. (Fig. 6E) Having learned not to trust the situation a follow-up exam was scheduled at which the recession had advanced and the MAG was more worrisome. (Fig. 6F) With a view to conservative therapy and addressing the prominent mandibular midline frenum a frenectomy was performed. (Fig. 6G) The area healed uneventfully and the patient was seen again months later. Marginal tissues appeared healthy, plaque was under control, recession had not advanced and a residual scar that would likely prove resistant to future recession was present. (Fig. 6H) Years had now passed and the young girl was approaching University with plans to attend outside the city. Although the area appeared stable the patient and her mother were concerned. With consideration of the journey thus far and looming dental inconsistency, the patient and mother elected for gingival grafting. (Fig. 6I) The area healed extremely well (Fig. 6J) and hopefully through a positive, slow paced dental experience, with an emphasis on hygiene, there will be no need for future treatment (in this area!).

Fig. 6A

Fig. 6B

Fig. 6C

Fig. 6D

Fig. 6E

Fig. 6F

Fig. 6G

Fig. 6H

Fig. 6I

Fig. 6J

Conclusion

Achieving successful long-term orthodontic therapy requires clinical intuition, continuous attention to detail and foresight. There are a myriad of concepts and clinical parameters to be considered. One critical factor that must remain top of mind is the horizontal position of the root relative to the surrounding alveolus. For cases where the root position becomes an issue, there exist several surgical approaches, that when implemented at the appropriate time, will compensate and ensure an optimal outcome.

Oral Health welcomes this original article.

References

- Thilander B. Infrabony pockets and reduced alveolar bone height in relation to orthodontic therapy. Semin Orthod. 1996;2(1):55-61.

- Wennstrom JL, Lindskog-Stokand B, Nyman S, et al. Periodontal tissue response to orthodontic movement of teeth with infrabony pockets. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1993;103:313-9.

- Yoshiaki H, Tadahiro T, Yoshihiro I. Clinical classification of tooth position in the alveolar bone housing with periodontal defects. J of Dental Sciences. 2021;16:795-798.

- Miller PD. A Classification of Marginal Tissue Recession. Int J of Perio and Rest Dent. 1985;2:9-13.

- Cairo F, et al. The interproximal clinical attachment level to classify gingival recessions and predict root coverage outcomes: an explorative and reliability study. J Clin Periodontol. 2011;38:661-666.

- Tarnow D, Magner AW, Fletcher P. The effect of the distance from the contact point to the crest of bone on the presence or absence of interproximal dental papilla. J Periodontol. 1992;63(12):995-6.

- Karring T, Numan S, Thilander B, Magnusson I. Bone regeneration in orthodontically produced alveolar bone dehiscences. J Periodont Res. 1982;17:309-15.

- Wennstrom JL. Mucogingival considerations in orthodontic treatment. Semin Orthod. 1996;2(1): 46-54.

- Murphy KG; Wilcko MT; Wilcko WM; Ferguson DJ. Periodontal accelerated osteogenic orthodontics: a description of the surgical technique. Journal of Oral & Maxillofacial Surgery. 2009;67(10): 2160-6.

- Wilcko MT; Wilcko WM; Pulver JJ; Bissada NF; Bouquot JE. Accelerated osteogenic orthodontics technique: a 1-stage surgically facilitated rapid orthodontic technique with alveolar augmentation. Journal of Oral & Maxillofacial Surgery. 2009;67(10):2149-59.

- Frost HM. The Regional Acceleratory Phenomenon: A Review. Henry Ford Hospital Medical Journal. 1983;31(1):3-9.

- Andlin-Sobocki A, Marcusson A, Persson M. 3-year observations on gingival recession in mandibular incisors in children. J Clin Periodontol. 1991;18:155-159.

About the Author

Dr. Adam graduated dental school from SUNY Buffalo and then completed his specialty training in Periodontics at the University of Toronto where he continues to teach in the Oral Reconstruction Centre and Graduate Periodontal Clinic while maintaining a full-time private practice. He has authored and presented on various periodontal and implant related topics and is an editor for a peer reviewed journal.

Dr. Adam graduated dental school from SUNY Buffalo and then completed his specialty training in Periodontics at the University of Toronto where he continues to teach in the Oral Reconstruction Centre and Graduate Periodontal Clinic while maintaining a full-time private practice. He has authored and presented on various periodontal and implant related topics and is an editor for a peer reviewed journal.