Immediate restoration of teeth that are not worth preserving, with implants in the aesthetically demanding anterior region, is a challenge in everyday practice.

The case study described here shows an immediate implantation to replace the right upper incisor with persistent apical inflammation in 2005. Since then, the patient has come to our practice at least twice a year for examination and prophylaxis. This gives us the opportunity to report on the long-term follow-up of our augmentation and implantation, as well as the prosthetic reconstruction.

In October 2005, the then 41-year-old male patient presented in our office: a non-smoker and his anamnesis showed nothing special. The patient reported a fall in adolescence, as a result of which the tooth partially fractured and the opened pulp tissue was removed and the root canal filled. The tooth was initially built up with composite until a few years later a part fractured again and the tooth could be reconstructed with a PFM crown and cast metal pin. However, over the course of time, recurrent infections had to repeatedly perform multiple root tip resections, as abscesses and fistulas kept forming.

Now the patient expressed a desire for aesthetic improvement, he did not feel any pain or sensitivity at this time. During the clinical examination, however, a fistula was found in the apical third of the vestibular area, as well as various scars from the previous resections and a dark gray discoloration of the surrounding soft tissue. Amalgam was probably used in one of the retrograde root fillings, or the post made of unknown metal oxidized. (Fig. 1)

Fig. 1

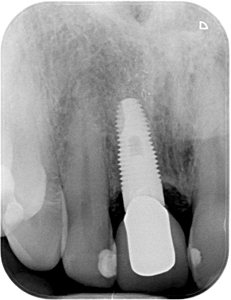

The tooth was neither loosened, nor could pocket depths >2mm be probed. Unfortunately, we did not have a cone beam CT at that time, as we use it as standard today in such cases. Therefore, a conventional two-dimensional x-ray or panoramic image and palpation of the area had to suffice to estimate how large the bony defect could be. (Fig. 2)

Fig. 2

In order to build up a three-dimensional defect in a reliably predictable way, the extent and location must be known. A single-stage procedure can only be carried out with a primary stable implant, which requires sufficient bone volume. If this is not available after extraction of the tooth, immediate implantation/restoration should be avoided and a two-stage procedure with the new contouring of the alveolar process should be used. Autologous bone blocks from the hip, calotte or the retromolar area as well as allogenic blocks come into question here. Today, as an alternative, we often augment with the shell technique, for this purpose a narrow block is removed from the retromolar region or from the external oblique line. Depending on the volume of the block, one or two thin cortical plates can be obtained to reconstruct the alveolar process. These are then fixed by means of osteosynthesis screws and/or plates in the same way as the block transplant, but at a distance from the local bone, which is then filled with particulate material. At that time, these procedures were already published, but only became established in the course of the following years. Various GBR techniques can be used to fill smaller defects, e.g. particulate replacement material and membranes at the same time as the insertion. The implant acts as a stabilizing element.

For an optimal surgical result, it is not only necessary to choose the ideal time for implant placement, but also the appropriate augmentation method and material. In addition, the influence of the soft tissue on the hard tissue must be considered in the aesthetic area. Recessions or dehiscences can be the difference between success and failure. In parallel to the bone reconstruction and the long-term stable anchoring of the implant, adequate soft tissue management must take place. In the this present case, the severe discoloration of the gingiva and the fistula made things worse. Since our patient refused a second bone harvesting site as well as the palatal connective tissue harvest, we had to resort to allogeneic and synthetic materials. Today we like to use platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) as an alternative to free connective tissue grafts. For this purpose, venous blood is taken from the patient and processed in such a way that stable membranes are created from the fibrin matrix enriched with platelets. These can then be applied in the desired region, which was not available to us in 2005 either.

We had therefore actually advised our patient against an immediate implantation, as the course and the result did not appear to be reliably predictable due to the long progression. The patient‘s constitution and muco-gingival relationships appeared to be favorable. He could definitely be counted to the morphogenic type B: many and thick circular and alveolo-gingival fibers, as well as sufficient blood vessels. In this type of soft tissue, the loss of the crevikular plexus and the dentogingival fibers can easily be compensated for after the tooth has been extracted.

After weighing up all the facts, the patient showed he was prepared to take risks and wanted the extraction and immediate implantation; we could only remove him from immediate loading using a temporary abutment and crown.

Due to the limited diagnostic options, in this case it seemed essential to obtain the best possible overview of the defect. Therefore, a generous exposure had to be carried out without additionally compromising the soft tissue, which was already damaged by the multiple surgical interventions of the past few years. One of the decisive factors for long-term success is the flap design. We therefore chose a crestal incision that preserved papillae, which was then extended further in the mesio-distal direction. The upper end of the cranial cuts should not extend over the defect, but should end caudally to the lower boundary of the bone window. From here a split flap was formed to partially remove the discoloration and tunneled subperiostally in order to ensure the best possible blood supply later. (Fig. 3) Fortunately, despite massive excochleation of the infiltrated granulation tissue, we were able to obtain a bone bridge with only a slight loss of crestal volume. (Fig. 4) As a result, the decision was made to augment with particulate bone substitute material and cover with an absorbable membrane. Allogenic granules from human donor bone were used. Due to their human structure and the still existing collagen parts, they function as a guide structure and framework for the controlled new formation. They have the potential for complete resorption with simultaneous autologous osteoneogenesis. Since the implant could be inserted with primary stability in the case of slight bleeding, and the bone bridge ensured stability of the local bone (Fig. 5), the focus was on the formation of new bone of the body and not on great volume stability. We therefore mainly chose cancellous particles with only a small amount of cortex. These lead to an optimal revascularization and thus to a maximum number of vital cells and new vital bone tissue.

Fig. 3

Fig. 4

Fig. 5

The optimal positioning of the implant shoulder is important for the subsequent formation of a natural gingival curve and the perfect aesthetic restoration. The implant-abutment border could ideally be placed 2mm below the buccal cement-enamel junction of the neighbouring teeth. The aproximal areas were spared and the natural tooth/alveolar curvature was preserved through the above-mentioned papillae gentle incision and the careful extraction. By using a tissue level implant, the polished part could be positioned extra-alveolar at the optimal height. In the present case, however, a little vestibular volume was missing, which we also augmented with the cancellous granules. (Fig. 6)

Fig. 6

The selection of the right implant is therefore actually the most important part.

To cover the defect, we split the fistula duct, but deliberately did not slit the surrounding periosteum. This should prevent dehiscences or the injection of soft and connective tissue fibers into the filled cavern. In addition, we fixed a resorbable pericardial membrane of porcine origin in two layers. In order to completely close the defect, we did without an additional sewn-in cover made from an autologous soft tissue graft or animal dermis. The softbrushing method was used here. The fibrous parts of the periosteum are stretched to the maximum by blunt processing and a cut can be avoided. The complete closure follows a protocol similar to a root coverage operation. (Fig. 7)

Fig. 7

Since our schedule did not allow the fabrication of a ceramic temporary, we polymerized a composite denture tooth with light basal pressure on the gingiva, which we reinforced palatally with a Teflon tape. (Fig. 8) This led to the soft tissue being as natural as possible during the six-month healing period. (Fig 9)

Fig. 8

Fig. 9

When comparing the postoperative X-ray with the control image after six months, (Fig. 10) apical osteoneogenesis is noticeable. (Fig. 11) The implant appeared stable and we were able to use a composite temporary crown on a PEEK abutment to support the gingival cuff when it was opened. We waited about 8 weeks until the impression was taken so that sufficient circular fibers could form. However, the aproximal contact point had to be corrected in relation to the implant shoulder and the papilla tip. (Fig. 12) Since the natural tooth curvature in the middle incisor (depending on the morphological type) is a difference from the aproximal to the buccal level of 2.5-2.8mm, the above-mentioned implant positioning and the correct design of the crown (and the temporary) lead to a controlled formation of the red and white aesthetic.

Fig. 10

Fig. 11

Fig. 12

The height of the implant head and the slightly palatal positioning can be clearly seen on the functional model. (Figs.13 & 14) This leads to a good blood flow in the sensitive buccal bone lamella, which is immensely important in terms of long-term success. Fig. 15 shows the final crown, the “stippling” of the mucosa can also be clearly seen. This is only possible through a sufficient formation of healthy alveologingival fibers, which unfortunately cannot always be achieved.

Fig. 13

Fig. 14

Fig. 15

In the present case, a large number of decisive criteria for a successful and aesthetically difficult reconstruction could be shown. These are not only crucial for short-term success, but also for maintaining this result.

However, in this case not everything went well. The patient presented a loosened crown after only four years. Surely the abutment should have been roughened and not polished, as we do it by default these days. But it also gave us the opportunity to check the situation under the crown: the surrounding tissue turned out to be unchanged and well supplied with blood (note the amount of attached mucosa). Pocket depths> 0.05mm could not be probed. So we simply recemented the crown. (Figs. 16 & 17)

Fig. 16

Fig. 17

Another check-up after ten years showed the same condition, (Fig. 18) as well as the final photo after 15 years. (Figs. 19 & 20) However, you can see that the neighbouring teeth have now discolored and could use bleaching from an aesthetic point of view. The implant, including the bone and the soft tissue, appear stable. (Fig. 21)

Fig. 18

Fig. 19

Fig. 20

Fig. 21

The small things such as flap design (split flap and expansion), implant type and bone substitute material are often responsible for a long-term positive course like this. However, the greatest effect is undoubtedly the patient‘s individual requirements, compliance and the famous little bit of luck.

I am pleased that I was able to present a case from our daily work here, even without much scientific evidence and structuring.

Oral Health welcomes this original article.

About the Author

Dr. Axel Wöst received his dental degree from University of Bonn/Germany in 1994. He continued with postdoctoral training in Oral Surgery and is a recognised specialist of Implant Dentistry and Periodontology since 1999. He has been in private practice since 1998 in Bad Honnef and Munich/Germany and founded another office in Unkel/Germany 2020.

Dr. Axel Wöst received his dental degree from University of Bonn/Germany in 1994. He continued with postdoctoral training in Oral Surgery and is a recognised specialist of Implant Dentistry and Periodontology since 1999. He has been in private practice since 1998 in Bad Honnef and Munich/Germany and founded another office in Unkel/Germany 2020.