Dental professionals must consider themselves the experts in pathological conditions of the oral cavity. This includes not only the teeth, but also the soft tissues and bone surrounding the teeth. There are no medical specialties that have comparable training and experience in the diagnosis and management of conditions affecting the oral cavity that dentists and dental hygienists have; therefore, patients are reliant on dental professionals when they develop lesions in the oral cavity. It is very important for dental professionals to appreciate this and continually update their oral pathology knowledge, since there is no form of dental treatment one could provide that would have as significant an impact on a patient’s well-being than the timely diagnosis and appropriate referral for treatment of a patient with a malignancy of the oral cavity. This article will outline keys to the successful management of patients with pathological lesions of the oral cavity.

Chief complaint/ history of chief complaint

The most important step in the evaluation of an oral pathology patient is to obtain a thorough and accurate history. The aphorism commonly used in health care, ’80% of the diagnosis is in the history’, often holds true with lesions of the oral cavity. This begins by asking the patient to describe, in their own words, what they have noticed. It is then up to the clinician to obtain a clear chronologic account of the patient’s chief complaint. As the clinician is asking questions it is very helpful to think of the possible diagnoses that fit with the patient’s presenting symptoms and ask questions to rule in or rule out those possibilities. Keep in mind that squamous cell carcinoma accounts for over 90% of oral cancers and that the most common presenting symptom of oral cancer is pain, although it is certainly possible to detect oral cancer before it is symptomatic. Pertinent questions to ask the patient include:

- How long has the condition been present?

- Does it fluctuate in size/severity, or does it come and go?

- Has it changed in size? If so, how rapidly?

- Has it changed in character?

- Are there any exacerbating or relieving factors?

- Are there any associated symptoms (pain, paresthesia, discharge, bleeding, dysphagia, dysarthria, etc.)?

- Are there any constitutional symptoms (fever, malaise, anorexia, weight loss, etc.)?

- Does the patient have an explanation for the condition (trauma, denture wear, toothache, new medication/oral health care product etc.)?

- Have they had any treatment for the condition? If so, what effect did this have?

- Have they had similar lesions in the past? If so, how was it managed?

Past medical history

It is important to recognize that there are many systemic conditions that may have oral manifestations, thus a complete medical history is essential. Furthermore, if a biopsy is indicated, it is important to know the patient’s coagulation and immune status to avoid complications involving bleeding and healing. Patients with cardiac conditions requiring antibiotic prophylaxis for the prevention of infective endocarditis will have to be managed properly. The patient’s general health status may also influence how they oral complaint may be managed. For instance, a patient on palliative therapy for cancer with a limited life expectancy may be best managed with no treatment for an asymptomatic lesion in the oral cavity.

Clinical exam

An appropriate clinical exam should include palpation of cervical lymph nodes and the major salivary glands. A screening exam of the cranial nerves may also be important for conditions affecting the oral cavity. The intraoral examination must include all oral hard and soft tissues. To avoid the tendency to focus on the site of the chief complaint, it is best to look at that area last. Once the lesion of concern is seen, it is very easy to neglect the remainder of the intraoral exam, potentially missing other lesions, which may or may not be related.

The lesion itself must be accurately described. It is best to avoid the use of the word ‘lesion’ when describing the clinical appearance of the pathologic entity. The use of appropriate clinical descriptors (Table 1) will aid the clinician in formulating a differential diagnosis. For instance, a vesiculobullous eruption suggests some specific conditions, while eliminating others. Use of clinical descriptive terms is also very helpful when communicating findings to other clinicians, including those to whom the patient may be referred. Good clinical photographs can also be very beneficial, particularly when referring the patient or following a condition over a period of time. An accurate clinical description of a condition should be recorded and must include:

- Clinical appearance using clinical descriptors

- Location

- Size

- Shape

- Colour

- Surface characteristics

- Consistency

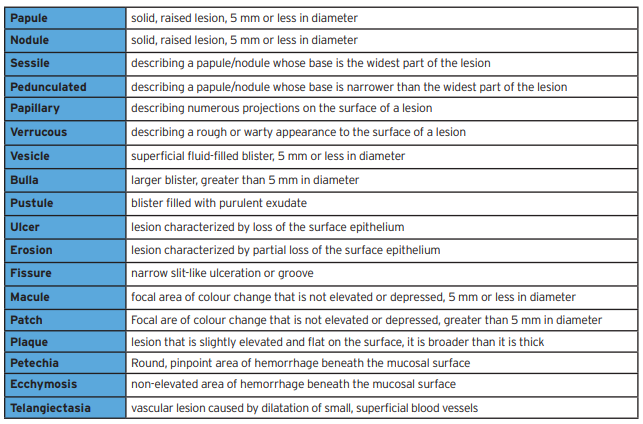

Table 1

Dental professionals are the only health care providers that examine the oral cavity in the absence of symptoms; thus, they are the only health care providers that may potentially detect serious oral health concerns before they become symptomatic. This knowledge is extremely important to appreciate in the setting of oral cancer. It is well known that detection of oral cancer at an early stage is associated with a better prognosis than those detected at a later stage. By taking a moment to examine both hard and soft tissues during a new patient exam and at recalls can dramatically influence the morbidity and mortality associated with oral cancer. Finding an asymptomatic oral cancer may not be as financially lucrative to the dental office as finding a tooth that needs a crown, but it will have a much great impact on the patient’s well-being. As oral health care providers it is our duty to provide this level of care to our patients.

Investigations

The results of the history and clinical exam will determine the need for further investigations. This may include plain film radiographs, CBCT, CT, MRI, and/or bloodwork.

Formulation of a differential diagnosis

At this point it is beneficial for the clinician to formally develop a differential diagnosis. This may require the clinician to consult an oral pathology textbook or atlas kept in the office. By developing a list of feasible diagnoses, it can help the clinician maintain a working knowledge of the oral pathology information they have acquired and potentially develop this knowledge further as they gain more clinical experience. This can also potentially save the patient a delay in appropriate treatment, or conversely, the time and money associated with an unnecessary referral.

Biopsy of lesion

Not all oral lesions require a biopsy or excision. For example, an asymptomatic fibroma of the buccal mucosa that is not interfering with function does not require treatment. Also, a classic case of asymptomatic reticular oral lichen planus involving the buccal mucosa and lateral tongue does not necessarily need to be biopsied. Indications for a biopsy include:

- Lesions that persist for > 2 weeks with no apparent etiology

- Suspected traumatic, inflammatory, or infectious lesions that do not respond to appropriate treatment within 2 weeks

- Lesions that interfere with function

- Bone lesions not specifically identified by clinical and radiographic exam

- Any lesion suspicious for malignancy

There is very little utility for cytologic smears and fine-needle aspiration (FNA) biopsies in the oral cavity. FNA biopsies do play a role in the diagnosis of neck masses as well as masses in the parotid and submandibular glands. Scalpel biopsies are the primary method of obtaining a biopsy of intraoral tissue.

Once it is decided that a lesion requires a biopsy, the clinician must determine if an incisional or excisional biopsy is most appropriate. Excisional biopsies are generally reserved for small lesions that are likely benign. Incisional biopsies are appropriate for lesions that are large, in an anatomically hazardous location (i.e. region of mental foramen, lingual nerve, parotid or submandibular duct opening), or potentially malignant.

The reason that an incisional biopsy is best for a potentially malignant lesion is that if the lesion does happen to be malignant the patient will require an oncologic resection of the tumor, which includes at the very least a one-centimeter margin of normal tissue in the peripheral and deep dimensions to ensure complete excision. Since it would be inappropriate to perform an excision such as this without a preoperative diagnosis, the patient will invariably require additional surgery if an excisional biopsy was performed. In most countries this type of surgery is performed by OMF or ENT surgeons with head and neck cancer training, thus a referral to a head and neck cancer surgeon is required. If there is no visible tumor evident, the head and neck cancer surgeon will likely have to perform a broader excision than would have been necessary if there was visible tumor, to ensure the tumor is completely excised. If a potentially malignant lesion is too small to obtain an incisional biopsy, it would be prudent to take a good clinical photo prior to the biopsy, so that the head and neck cancer surgeon can later see exactly where the tumor was to aid in planning the margins of excision.

Referring the pathology patient

Clinicians who receive referrals for pathological lesions of the oral cavity triage those referrals. An appropriate referral will include a history of the lesion, an accurate clinical description of the lesion, the response to any previous treatment, and a differential diagnosis or level of perceived urgency. A good clinical photo can also be very beneficial. A well written referral can minimize unnecessary delays in the patient being seen by the specialist.

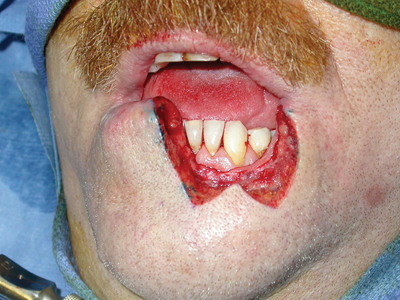

For example, a well-written referral letter for the patient seen in Fig. 1 would be as follows:

Please see this 64 year-old female with a 3-month history of a painful 2cm ulceration with rolled margins and surrounding induration in the anterior left floor of mouth. There is no palpable cervical adenopathy. There was no improvement with a course of nystatin oral rinse prescribed by her physician. The lesion is very suspicious for squamous cell carcinoma. Please see urgently.

Fig. 1

A referral letter such as this is certainly more valuable than one which simply requests, “assess floor of mouth lesion”. A poor referral letter may result in an inappropriate delay in the patient being seen if it is a malignancy, or inappropriately delaying other patients who may have more urgent needs from being seen in a timely fashion. Furthermore, the specialist who receives numerous inadequate referrals from the same dental office for benign conditions may begin triaging all similarly inadequate referrals from this office as low urgency, which may result in delays for patients with truly urgent needs.

Biopsy tips

Incisional vs Excisional biopsy

Once it is decided that a lesion requires a biopsy, the clinician must determine if an incisional or excisional biopsy is most appropriate. Excisional biopsies are generally reserved for small lesions that are likely benign. Incisional biopsies are appropriate for lesions that are large, in an anatomically hazardous location (i.e. region of mental foramen, lingual nerve, parotid or submandibular duct opening), and potentially malignant.

The reason that an incisional biopsy is best for a potentially malignant lesion is that if the lesion does happen to be malignant the patient will require an oncologic resection of the tumor, which includes at the very least a one-centimeter margin of normal tissue in the peripheral and deep dimensions to ensure complete excision. Since it would be inappropriate to perform an excision such as this without a preoperative diagnosis, the patient will invariably require additional surgery if an excisional biopsy was performed. In most countries this type of surgery is performed by OMF or ENT surgeons with head and neck cancer training, thus a referral to a head and neck cancer surgeon is required. If there is no visible tumor evident, the head and neck cancer surgeon will likely have to perform a broader excision than would have been necessary if there was visible tumor, to make sure the tumor is completely excised. If a potentially malignant lesion is too small to obtain an incisional biopsy, it would be prudent to take a good clinical photo prior to the biopsy, so that the head and neck cancer surgeon can later see exactly were the tumor was to aid in planning the margins of excision.

Tissue to include in the biopsy

A biopsy of a lesion suspicious for dysplasia or malignancy does not have to include normal surrounding tissue in the biopsy. The recommendation that a biopsy contain normal surrounding tissue does apply to mucocutaneous diseases such as mucous membrane pemphigoid, pemphigus vulgaris, and lichen planus. When these conditions are in your differential diagnosis a biopsy of an area of ulceration with no epithelium may be non-diagnostic.

When obtaining an incisional biopsy of a larger area, particularly one with a non-homogenous appearance, sampling error may result in a diagnosis that in not representative of the entire lesion. In these cases, it is important to biopsy the area that appears most concerning. If the lesion includes white and red areas, some of red area must be included in the biopsy, although it would be reasonable to have a portion of both. (Fig. 2) It is known that areas of leukoplakia have up to a 25% chance of being dysplasia or malignancy at the time of biopsy, whereas erythroplakia has up to a 90% chance of the same.

Fig. 2

Appropriate depth of a soft tissue biopsy

The depth of invasion of oral squamous cell carcinoma is known to directly correlate with the risk of cervical metastasis and thus influences the patient’s prognosis. As a result, effective January 2018 the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) modified the TNM staging system for squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity (Table 2).1 In addition to the maximum dimension of the primary tumor, the depth of invasion of the primary tumor is now incorporated into the T (tumor) stage. Furthermore, many head and neck cancer surgeons recommend that patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma undergo an elective neck dissection when the depth of invasion of the primary tumor is 4mm or greater, in the absence of clinical or radiographic evidence of cervical lymph node metastasis (N0).2 The justification for this is that with greater than 4mm depth of invasion, the risk of occult cervical metastasis is significant enough that the prognosis with an elective neck dissection is better in comparison to observation of the neck with intervention once cervical metastasis becomes clinically or radiographically evident.3

Table 2

With this knowledge, any lesion suspicious for malignancy should be biopsied with a depth of a least 5mm to aid in initial staging of the tumor and surgical planning. Clearly, this depth in not possible in the region of the alveolar mucosa/attached gingiva or some regions of the hard palate. In these locations, the full thickness of the soft tissue down to bone is advisable.

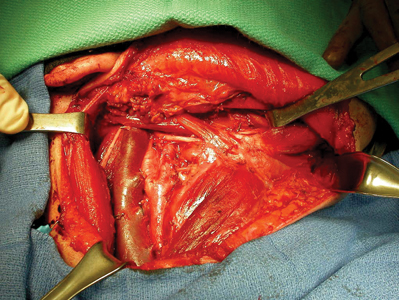

Lower lip biopsies

Biopsies and excisions of lesions on the face, including the vermillion of the lips, are best oriented parallel to Langer lines of skin tension. By orienting the incisions in this way there is less tension on the wound and the resulting scars are less visible, since they are parallel to the natural skin creases or wrinkles. On the vermillion of the lower lip, a common site for squamous cell carcinoma, these lines run in a vertical plane. The appropriate treatment of a squamous cell carcinoma involving up to one third of the lower lip is a wedge or W-excision with primary closure. (Fig. 3) This results in a vertical wound parallel Langer lines of skin tension and restoration of the contour of the lower lip. Biopsies of lesions on the vermillion should also be oriented in the same plane. A horizontally oriented biopsy of a potential squamous cell carcinoma of the lower lip often extends medially or laterally beyond the lesion itself. If the lesion is malignant the wedge excision will then have to extend beyond the biopsy margin to ensure complete excision of the tumor, resulting in the loss of more lip than necessary.

Fig. 3A

Fig. 3B

Fig. 3C

Fig. 3D

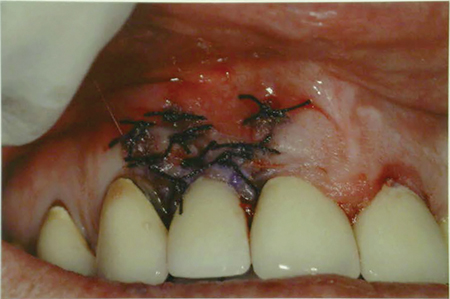

Do not graft over biopsy sites of potentially malignant gingival lesions

When performing an excisional biopsy of a potentially malignant lesion, do not place a gingival graft over the site prior to obtaining a histopathologic diagnosis. (Fig. 4) If the lesion is malignant, the graft becomes an unnecessary expense for the patient and likely increases the margin of resection that will be necessary. Very broad areas of attached gingiva can be excised and left to heal by secondary intention. As long as there is no periodontal bone loss, the attached gingiva will generally return to the presurgical level without recession or need for grafting.

Fig. 4A

Fig. 4B

Fig. 4C

Fig. 4D

Fig. 4E

Do not throw tissue out

The case seen in Fig. 4 brings to attention another important point; any tissue excised from the oral cavity should be sent for histopathological evaluation no matter how benign it may appear. The erythematous gingiva on the labial aspect of tooth #1-2 was excised by another clinician almost 2 years earlier; however, it was not sent to pathology. All clinicians will likely encounter pathology results that surprise them at some point in time. It is always better to be safe than sorry.

Do not perform any dental treatment in the area of a biopsy until the diagnosis is established

It is generally advisable to not perform any dental treatment in the area of a pathological lesion until the lesion has been biopsied and the definitive diagnosis established. Fig. 5 provides an example of a palatal nodule that was excised and submitted to pathology, while at the same time a mucogingival graft was harvested from a site immediately adjacent to the biopsy and grafted to the mandibular anterior gingiva. The palatal nodule was found to be a mucoepidermoid carcinoma. The patient then required an excision of the entire graft form the anterior mandible to determine if there was any malignancy within it.

Fig. 5

Similarly, when the soft tissue around teeth appears abnormal and there is osteolysis of the underlying bone, it is important to establish a diagnosis prior to providing treatment such as scaling and root planing or dental extractions. (Fig. 6) Although periodontal disease is the most common cause of bone loss and tooth mobility, isolated areas of osteolysis, particularly when the overlying gingiva appears abnormal, must elevate the clinicians index of suspicion that a more worrisome process is present. It is important to avoid delays in the diagnosis of malignancies.

Fig. 6A

Fig. 6B

Fig. 6C

Conclusion

As health care providers, dental professionals have a responsibility to establish and maintain the optimal oral health of their patients. To do so requires just as much attention to the soft tissues of the oral cavity as it does to the teeth. To detect oral cancer at an early stage and improve the prognosis of the disease, clinicians must routinely examine the soft tissues, and maintain an elevated index of suspicion. When a condition does not respond as one would expect to appropriate therapy, one must reconsider the diagnosis. Timely and appropriate biopsies and/or referrals can have a profound influence on the patient’s treatment and prognosis. A sound foundation of oral pathology knowledge is essential in this process.

Oral Health welcomes this original article.

References

- Amin MB, Edge S, Greene F, Byrd DR, Brookland RK, Washington MK, Gershenwald JE, Compton CC, Hess KR, et al. (Eds.). AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th edition. New York: Springer: 2016.

- Huang SH, Hwang D, Lockwood G, Goldstein DP and O’Sullivan B. Predictive value of tumor thickness for cervical lymph-node involvement in squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity: a meta-analysis of reported studies. Cancer: Interdisciplinary International Journal of the American Cancer Society. 2009; 115(7); 1489-1497.

- Caldeira PC, Soto, AML, de Aguiar MCF and Martins CC. Tumor depth of invasion and prognosis of early-stage oral squamous cell carcinoma: A meta-analysis. Oral Diseases. 2020; 26(7); 1357-1365.

About the Author

Dr. Chad Robertson graduated from the University of Western Ontario, Faculty of Dentistry in 1996. He obtained his MD and MSc in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery from Dalhousie University in 2003. He completed a fellowship in the surgical management of oral cancer at the University of California, San Francisco. He then returned to Dalhousie University where he is now an Associate Professor and Chair of the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Sciences. Dr. Robertson is also the Head of the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery for the Central Zone of Nova Scotia Health, Chief Examiner in OMFS with the Royal College of Dentists of Canada, and President-elect of the Canadian Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons.

Dr. Chad Robertson graduated from the University of Western Ontario, Faculty of Dentistry in 1996. He obtained his MD and MSc in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery from Dalhousie University in 2003. He completed a fellowship in the surgical management of oral cancer at the University of California, San Francisco. He then returned to Dalhousie University where he is now an Associate Professor and Chair of the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Sciences. Dr. Robertson is also the Head of the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery for the Central Zone of Nova Scotia Health, Chief Examiner in OMFS with the Royal College of Dentists of Canada, and President-elect of the Canadian Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons.