Abstract

The identification of lesions within the osseous structures in children is essential to ensure timely surgical intervention, and to minimize or correct hindrances to the development of a healthy dentition and bone structure. These lesions tend to present in the absence of symptoms, are slowly growing, and are commonly identified either as a secondary finding relating to the observation of an unerupted tooth, or during routine workup for orthodontic therapy and recall radiographic evaluation. The finding of pathology in children can be anxiety-provoking for parents, and diagnosis and successful surgical management is of paramount importance. The purpose of this article is to present an overview of benign odontogenic lesions that can be found in children.

Classification of Pathologic Lesions

Primary cysts and benign tumours that arise within the maxilla or mandible are classified into odontogenic and non-odontogenic etiologies. Of these, the odontogenic lesions are more common in children than non-odontogenic lesions. Odontogenic lesions consist of cysts, benign odontogenic tumours, and malignant odontogenic tumours.1,2

Odontoma

The odontoma is a benign odontogenic tumour that is derived from both odontogenic epithelium, which gives rise to its enamel component, and mesenchymal elements of the dental follicle, which produces the dentin component. Odontomas are one of the more common odontogenic lesions found in children.1,2 Occurrence is more common in the mandible than in the maxilla, but lesions can occur in either jaw. In general, these lesions present as two variants: the compound odontoma, which presents in the form of multiple small tooth-like structures, and the complex odontoma, which presents as an irregularly shaped calcified mass of odontogenic tissues. Some lesions will present as a combination of these variants, and are thus classified as complex-compound odontomas. The early clinical presentation of an odontoma may be associated with delayed eruption of teeth, and/or painless expansion of the alveolar process. Swelling of the mucosa or secondary infection is uncommon. Radiographically, these lesions commonly appear as a disorganized calcified mass that is often of a mixed radiolucent-radiopaque appearance. Odontomas do not induce resorption of roots adjacent to the lesion. Both complex and compound odontomas are treated by enucleation or curettage with complete cure and no known tendency toward recurrence. In the case of compound odontomas, the surgeon must exercise care to remove all portions of the lesion. Reconstructive graft procedures are not required; however, teeth that are significantly displaced or delayed in their eruption may require secondary surgical exposure and orthodontically guided eruption (Figs. 1A-1I).

Fig. 1A

Fig. 1B

Fig. 1C

Fig. 1D

Fig. 1E1

decortication.

Fig. E2

decortication.

Fig. 1F

Fig. 1G

Dentigerous Cyst

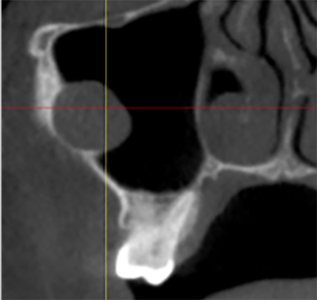

The dentigerous cyst arises from the dental follicle of unerupted or developing teeth. After the radicular cyst, the dentigerous cyst is the second most common cystic lesion found within the jaws. Most commonly, the lesion is found in the posterior maxilla or mandible, in association with an impacted third molar, but may also be identified in the anterior maxilla in association with impaction of the maxillary cuspid. These lesions are often asymptomatic, and detected on radiographic examination; however, expansion of the alveolar process can be a presenting feature, particularly with larger lesions. Radiographically, dentigerous cysts present as well circumscribed radiolucencies, associated with the crown of an unerupted tooth. The tooth associated with the lesion is often displaced, with possible displacement or resorption of roots of adjacent teeth. Large lesions that encroach on the inferior alveolar nerve branches rarely result in paresthesia, so long as secondary infection and pathologic fracture do not occur. The differential diagnosis for the radiographic finding includes odontogenic keratocyst, ameloblastoma, or ameloblastic fibroma. If the lesion occurs in the anterior maxilla, the differential diagnosis would include an adenomatoid odontogenic cyst in young patients. CT imaging can be helpful in distinguishing between cystic lesions and solid tumours. Aspiration of the lesion prior to removal rules out a lesion of vascular etiology. The finding of straw coloured fluid within the aspirating syringe provides confirmation to the surgeon that it is appropriate to proceed with enucleation of the cyst.

Fig. 2

Odontogenic Keratocyst

The nomenclature for this lesion has gone through multiple changes; in 2005 the lesion was reclassified by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a keratocystic odontogenic tumour. The name of the lesion was changed back to its original name of odontogenic keratocyst (OKC) by the WHO in 2017 due to a perceived lack of evidence of its behaviour as a tumour3; however, this reversal of terminology remains controversial. Over 100 cases of malignant transformation of OKC’s have been reported, with a tenfold increase in the incidence of development of squamous cell carcinomas within the OKC relative to other odontogenic cysts. This lesion is a unique and specific entity, and displays the most aggressive and recurrent behaviour of all of the odontogenic cysts. Characteristics of both a cyst and a benign tumour are displayed. Lesions may present either in association with impacted teeth, with a radiographic appearance similar to that of a dentigerous cyst, or as radiolucency in the absence of an impaction.

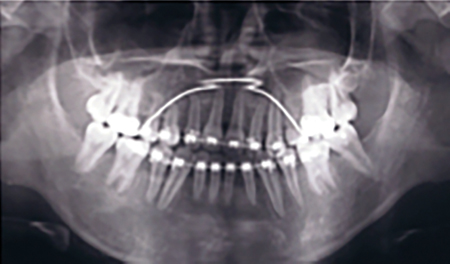

The OKC has a peak incidence in the teenage years and 20’s, but can occur at any age. The mandible exhibits lesions more commonly than the maxilla, with the predominance of lesions occurring in the third molar region (Fig. 3).

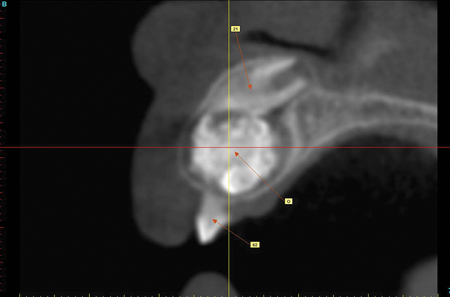

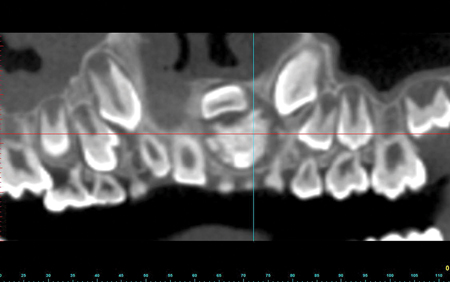

Fig. 3A

Fig. 3B1

Fig. B2

Fig. 3C

Fig. 3D

In children, OKC’s occur as part of the basal cell nevus (Gorlin) syndrome, with a common presentation of multiple lesions. Between 50-60 per cent of patients with the syndrome present with large calvaria and hypertelorism. Other features associated with syndrome include basal cell carcinomas that can typically appear on areas that are either exposed or non-exposed to the sun, palmar and plantar pitting, bifid rib formation, calcification of the falx cerebri, and other skeletal and varied abnormalities.

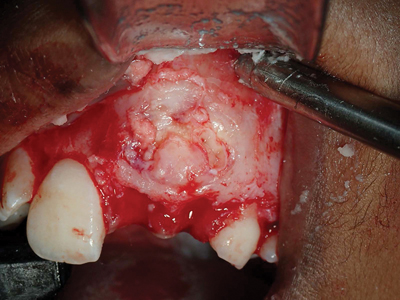

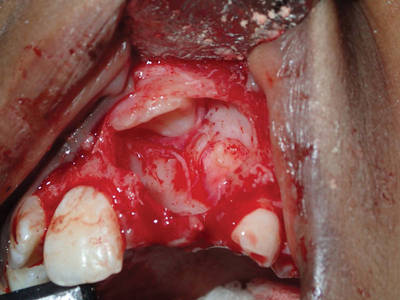

Treatment of the OKC is enucleation and curettage. Marsupialization can be utilized in cases of lesions associated with impacted teeth in children, which can facilitate bringing the associated tooth into function (Fig. 4). Resection surgery is indicated in cases where there have been multiple recurrences following enucleation and curettage, or in cases of extremely large lesions not amenable to curettage. Recurrence rates for OKC’s are reported to range from 5% to 70%, with a wide reported variation depending on the nature of the study, and technique used for treatment. Treatment of the cystic defect intraoperatively with adjuncts such as Carnoy’s solution and 5-fluorouracil has been shown to significantly reduce the risk of recurrence.4,5 Patients with OKC’s require long-term radiographic follow-up due to the high risk for development of recurrent lesions.

Fig. 4A

Fig. 4B

Fig. 4C

Fig. 4D

Fig. 4F

Fig. 4G

Fig. 4H

Fig. 4I

Fig. 4J

Fig. 4K

Fig. 4L

Ameloblastoma

The ameloblastoma is a tumour of the odontogenic epithelium, accounting for less than 1% of all odontogenic cysts and tumours. Despite their rarity, this lesion must be considered in the differential diagnosis of both unilocular and multilocular radiolucencies of the jaws. Central ameloblastomas are sub classified as unicystic, multicystic or solid lesions, with the unicystic variant bearing a marked resemblance to the dentigerous cyst and odontogenic keratocyst, both in terms of radiographic presentation and a tendency to occur during the teenage years. Unicystic ameloblatomas have a predilection to occur in the mandible. Clinically, the lesion is typically painless, although facial swelling may occur. The radiographic appearance is that of a unilocular radiolucency associated with an impacted third molar. Cortical expansion and displacement or resorption of adjacent tooth roots may occur. In younger children a similar presentation can result from the presence of an ameloblastic fibroma. Treatment of both unicystic ameloblatomas and ameloblastic fibromas consists of enucleation, with careful examination of the surgical specimen by the pathologist to fully diagnose the extent of the tumour (Fig. 5). Unicystic ameloblatomas require close follow-up due to the potential for recurrence. In some cases of unicystic ameloblastoma, a marginal resection may be required to ensure eradication. The other variants of ameloblatoma, namely the multicystic and solid variants, typically occur in adultdhood, and require resection with a 1.5 cm margin to effect cure.

Fig. 5A

Fig. 5B

Fig. 5C

Fig. 5D

Fig. 5E

Fig. 5F

Fig. 5G

In children, ameloblastic fibromas are more common than unicystic ameloblatomas, and can present radiographically as either a unilocular or multilocular radiolucency. Similar to the other lesions presented, they can be associated with unerupted teeth, more commonly in the mandible. In some cases, calcifications may be present within the lesion, and the lesion is then referred to as an ameloblastic fibro-odontoma. This variant may have a similar radiographic appearance to the odontoma. These lesions are treated with enucleation and curettage, with a low rate of recurrence.

Conclusion

This article has reviewed the most common odontogenic cysts and benign tumours found within the paediatric population. The clinician is reminded of the importance of prompt recognition of clinical and radiographic anomalies, and referral to an oral and maxillofacial surgical specialist for definitive diagnosis and management of lesions upon their discovery. Surgical removal of third molars prior to the development of pathology should be considered in patients who have insufficient physiologic space for eruption and maintenance at a time when the post-surgical healing is optimal and the risk of complications is low.6

Oral Health welcomes this original article.

References

- Marx RE, Stern D. Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology: Quintessence, 2003. Print.

- Kaban LB, Troulis MJ. Paediatric Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery: Saunders, 2004. Print.

- Wright JM, Vered M. Update from the 4th Edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Head and Neck Tumours: Odontogenic and Maxillofacial Bone Tumors. Head Neck Pathol. 2017 Mar; 11(1): 68–77.

- Blanas N, Freund B, Schwartz M, Furst IM. Systematic review of the treatment and prognosis of the odontogenic keratocyst. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000 Nov;90(5):553-8.

- Ledderhof NJ, Caminiti MF, Bradley G3, Lam DK. Topical 5-Fluorouracil is a Novel Targeted Therapy for the Keratocystic Odontogenic Tumor. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2017 Mar;75(3):514-524. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2016.09.039. Epub 2016 Sep 30.

- Management of Impacted Teeth. American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons White Paper, 2016.

About the Author

Dr. Marshall Freilich is Coordinator of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery at Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital, and staff Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeon at Humber River Hospital. He maintains a private practice dedicated to surgical care for children and adults in Toronto, Ontario.

Dr. Marshall Freilich is Coordinator of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery at Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital, and staff Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeon at Humber River Hospital. He maintains a private practice dedicated to surgical care for children and adults in Toronto, Ontario.

RELATED ARTICLE: Psoriasin: A New Biomarker in the Identification of Cancer Risk in Oral Lesions