The severely worn dentition is one of the most challenging circumstances for oral rehabilitation. Due to severe dental abrasion, the vertical dimension of occlusion (VDO) is decreased, dentinal surfaces are exposed, and there is a lack of functional occlusion. Functional movements are missing or have been modified. Premature contacts and interferences due to missing teeth and positional alteration of the existing dentition are also are present (Figs. 1, 2).

Fig. 1

Fig. 2

For affected patients, temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorders are quite common; cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) of the TMJ is highly recommended for an appropriate diagnosis. Patients with severe dental abrasion often suffer from pain due to muscular contraction, as well. These two factors are typically the main complaints that lead patients to the dental practice. The following is an overview of techniques and procedures that are useful for full mouth rehabilitation.

Clinical Considerations

The first step is to solve the acute problems: pain and TMJ disorders. A centric relation (CR) splint is the initial step in the rehabilitation process (Fig. 3). The splint may be full-mouth or anterior only. Care must be taken with longer-term, night only, anterior splints to avoid dental migrations. A Lucia Jig is used to determine the CR, and bite registration wax is used for a reliable occlusal registration. It is recommended that the splint be worn for at least 6 weeks. During this time, the TMJ pathology can be analyzed while there is muscular pain relief. When significant muscle contractions were present initially, the CR determination should be repeated after 6 weeks. During the 6 week period, muscle relaxation is achieved, resulting in a slightly modified CR, and a new registration. However, not all clinical situations are amenable to this direct approach; some TMJ pathologies requiring more extensive treatment.

Fig. 3

After the minimum 6 weeks, the dental technician prepares a wax-up. The initial impression may be taken digitally or utilizing conventional impression materials. The wax-up may also be digital or conventional.

The occlusal goals for achieving long-term stability in total rehabilitation are:1-3

- Stable holding contacts on all teeth when condyles are in centric relation (CR) or adaptive centric position (ACP)

- Anterior guidance in harmony with the envelope of function

- Immediate disclusion of the posterior teeth in protrusion

- Immediate disclusion of the posterior teeth on the non-working side

- Immediate disclusion of the posterior teeth, whenever possible, on the working side

In order to analyze the occlusion from functional and aesthetic perspectives, a mock-up is required. The cervical-incisal length and ratio, the visibility of the anterior teeth in different lip positions (rest, smile, and various functional movements), the fixed gingiva levels and their zenith points are all evaluated. If indicated at this stage, gingival surgery can be undertaken to optimize aesthetic results. In order to conserve as much enamel and dentin as possible, final preparations are performed through the mock-up (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4

The key elements for successful total rehabilitation treatment are:4-6

- Augmentation of vertical occlusal dimension

- Minimally invasive occlusal preparations (less than 1.0mm)

- Minimally invasive marginal preparation to achieve optimal bonding, preferably to enamel

- Lithium disilicate ceramics for posteriors to increase restorative strength

- Adhesive bonding of all restorations

As reported in many studies, resin enamel bonds are both reliable and durable. The presence of enamel at the preparation margin offers an ideal seal to prevent the ingress of oral fluids and bacteria. When the cavity margins are bonded to enamel, internal dentinal bonds are more durable as well (even simplified, more hydrophilic adhesives survive due to the shielding effect of bonded enamel that prevents diffusion of water across the bonded interface).7-9

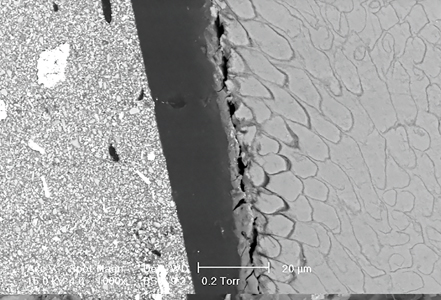

The bigger the difference between the acid solubilities of the enamel periphery and the prism core, the stronger the bond. Resin tags up to 25µ in length and 6µ in diameter are formed into micro-porosities of the conditioned enamel, providing a long-lasting micromechanical bond (tensile and shear stress are 20-25 MPa, higher than the polymerization shrinkage surface tension of the composite resin at 16-18 MPa (Figs. 5, 6, 7, 8).4,10-12 (Acid etching of the enamel – prisms cut longitudinally and transversally displaying the three acid etch patterns)

Fig. 5

Fig. 6

Fig. 7

Fig. 8

While enamel is predominantly mineral in composition, dentin is approximately 30% organic. Dentin permeability depends on the dentin tubule diameter. The smear layer extends 1-10µ into the outer part of the dentinal tubule. The smear layer thickness is directly proportional to the bur grain size. Despite the smear layer’s weak bond to the underlying dentin, micro- and nano-leakage phenomena still pose major clinical challenges (Fig. 9).4,13-15

Fig. 9

With minimally invasive preparation restricted to the enamel, local anesthesia is rarely necessary. Vitality of all teeth is maintained (Figs. 10, 11). Preparations for the ceramic restorations are less than 0.3-0.5mm in depth. Enamel bonding techniques make many preparations types possible (partial veneers, table-tops, veneers, double veneers, crowns) (Figs. 12, 13).

Fig. 10

Fig. 11

Fig. 12

Fig. 13

The minimal thickness of the ceramic restorations requires a judicious use of cement shading. Try-in pastes are utilized to determine which specific cement (and shade) is best. In the case of darkly colored non-vital teeth, intra-coronal bleaching procedures are sometimes required prior to cementation. In order to, enhance the seal, cementation should be performed under rubber dam moisture control (Fig 14).

Fig. 14

Case report

A 38-year old male patient with severe dental attrition and abrasion (Figs. 15, 16) desired to secure a long-lasting functional and esthetic result. A total rehabilitation in CR was recommended. This was the best means of providing an increase of VDO without disturbing normal TMJ functionality. Furthermore, it was possible to conserve the enamel surfaces at all the margins, providing an enhanced and predictable bonding of the restorations.

Fig. 15

Fig. 16

An anterior splint was applied for 6 weeks. No TMJ pathology was observed. The muscle relaxation in CR provided the patient with the clear perception of the benefits of the proposed treatment.

There were two main reasons to fabricate the mock-up (Fig. 17): the first was to determine the esthetic parameters of the final restorations (length and shape of the anterior teeth, zenith points, cervical lines, contour lines, etc.), and the second was to assure minimally invasive preparations (Fig. 18) by using the mock-up as a prep guide.

Fig. 17

Fig. 18

Lithium disilicate was used for the final ceramic restorations. (Figs. 19, 20) The strength of this material assures good resistance and occlusal support in the posterior areas, along with minimally invasive occlusal preparations as the VDO is increased. Bonding of the restorations was accomplished with a 5th generation bonding system (Syntac, Ivoclar Vivadent, Schaan, Liechtenstein). The patient’s post-operative clinical situation was greatly enhanced and esthetically improved. (Figs. 21, 22, 23).

Fig. 19

Fig. 20

Fig. 21

Fig. 22

Fig. 23

The 6-year follow-up clearly demonstrates the stability and success, full functionality and excellent esthetics, of this technique. (Fig. 24).

Fig. 24

Oral Health welcomes this original article.

References

- John C Cranham, Peter E Dawson. Relating oclusal treatment to the Dawson classification. Aegis April 2010. Volume 3; Issue 1.

- Dawson PE, Centric Relation, Continuum (NY) 1980, 49-60.

- Dawson PE, New definition for relating occlusion to varying conditions of the temporomandibular joint. J Prosthetic Dent. 1995: 74(6): 619-627.

- Lazarescu F, Ed. Comprehensive Esthetic Dentistry. Quintessence Pub Co. 2015; 142-146; 495-511.

- Fradeani M. Barducci G. Bacherini L. Brennan M. Esthetic rehabilitation of a severely worn dentition with minimally invasive prosthetic procedures. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent 2012: 32(2):135-147.

- Freedman G. Contemporary Esthetic Dentistry. St Louis: Mosby 2012.

- Cardoso MV de Almeida, Neves A, Mine A, Coutihno E, Van Landuyt K, De Munk J, Van Meerbeck B: Current aspects of bonding effectiveness and stability in adhesive dentistry. Aust Dent J 2011; 56 Suppl 1:31-44 PubMed 21564114.

- De Munk, Van Meerbeck B., Yoshida Y, Inoue S, Vargas M, Suzuki K, Lambrechts P, Vanherle G: Four-year water degradation of total etch adhesives bonded to dentin. J Dent. Res 2003; 82: 130-40; PubMed 12562888.

- Reis AF, Giannini M, Pereira PN. Effects of a peripheral enamel bond on long-term effectiveness of dentin bonding agents exposed to water in vitro. J. Biomed Matter Res B. App Biomater 2008; 85:10-7 Pubmed 17618515.

- Carvhlo R. Effects of prism orientation on tensile strength of enamel. J Adhesive Dent 2000;2-4:251-257.

- Van Meerbeck B, De Munck J, Yoshida Y, Inoue S: Adhesion on enamel and dentin: Current status and future challenges: Oper Dent 2003; 28:215-235.

- Roulet JF, Degrange M (eds). Adhesion. The silent revolution in dentistry. Chicago. Quintessence 2000: 29-44.

- Van Landuyt KL, Peumans M, Coutihno E, Suzuki K, Van Meerbeck B. Influence of the chemical structure of functional monomers of their adhesive performance. J Dent Res 2008: 87: 757-761.

- Eliades GC, Watts DC, Eliades T: Dental Hard tissues and bonding: interfacial phenomena and related properties: Heidelberg, Springer 2005.

- Pashley D, tao L, Boyd L, King G, Horner J: Scanning electron microscopy of the substructure of smear layer in human dentine. Arch Oral Biol 1983; 33: 265-270.

About the Author

Dr. Florin Lazarescu, President of the European Society of Cosmetic Dentistry (ESCD) and Founding Member and Director, Romanian Society of Esthetic Dentistry (SSER), Editor-in-Chief of Dental Tribune Romanian Edition. He is the author of numerous publications, and the editor of and a contributing author to the Romanian book Immersion in Esthetic Dentistry (SSER, 2013) – republished in English as Comprehensive Esthetic Dentistry (Quintessence, 2015), and in Chinese (Quintessence China, 2017). Dr. Lazarescu owns a private dental practice in Bucharest, Romania and in his work focuses on esthetic dentistry with an emphasis on all-ceramic and implant restorative procedures.

Dr. Florin Lazarescu, President of the European Society of Cosmetic Dentistry (ESCD) and Founding Member and Director, Romanian Society of Esthetic Dentistry (SSER), Editor-in-Chief of Dental Tribune Romanian Edition. He is the author of numerous publications, and the editor of and a contributing author to the Romanian book Immersion in Esthetic Dentistry (SSER, 2013) – republished in English as Comprehensive Esthetic Dentistry (Quintessence, 2015), and in Chinese (Quintessence China, 2017). Dr. Lazarescu owns a private dental practice in Bucharest, Romania and in his work focuses on esthetic dentistry with an emphasis on all-ceramic and implant restorative procedures.

To see more articles from the July/August 2020 issue, please click here!