The congenital absence of one or more teeth is the most common anomaly of dental development in humans. Several terms have been used in the literature to describe this anomaly. Agenesis is considered to be the most suitable term, since from its’ Greek derivation it describes the failure of an organ to develop during embryonic growth.1,2,3 The prevalence of maxillary lateral incisor agenesis varies between 1.5%-2%,4 this data may change according to the population studied, race and gender. It is known that Caucasians and females are more affected by tooth agenesis.1,3,5,6. Moreover, bilateral maxillary lateral incisor agenesis is more frequent.7

Several hypotheses regarding the etiology of this condition have been proposed, they include genetic influence, environmental and systemic factors and, an evolutionary pattern in which the number of teeth is reduced in response to a decrease in jaw size.1,2,3,5,6

The patient with agenesis of maxillary lateral incisors has aesthetics as a fundamental concern.8 This condition can affect the individual’s psychosocial development, interpersonal interactions and create functional and phonetic problems.1,3 An early diagnosis may provide the patient and family with additional treatment alternatives and, perhaps allow the orthodontist to intercept future periodontal and restorative issues.10 The preferred treatment alternative should be the least invasive, with optimal conservation of dental structures, good aesthetics and function, while still satisfying the patient’s expectations.10-20

An interdisciplinary treatment approach is recommended for obtaining the most predictable outcomes.11-15 Selecting the appropriate treatment is a complex decision in which the orthodontist considers many factors including: the patient’s age, growth pattern, malocclusion, apical position of maxillary anterior roots, mechanotherapy, facial profile, smile line, canine morphology and color, psychosocial factors and personal preferences.8,3,10-13

Optimal treatment of missing maxillary lateral incisors remains controversial, despite the existing literature.10-13,18 In the following paragraphs a brief review of the clinical suggestions for the treatment of this condition will be conducted and clinical scenarios will be presented.

The orthodontic management for agenesis of maxillary lateral incisors follows two basic forms.10-20

- Orthodontic space closure through the mesial movement of posterior teeth.

- The maintenance or opening of spaces followed by prosthetic replacement.

ORTHODONTIC SPACE CLOSURE BY CANINE SUBSTITUTION

1. Indications

a) Malocclusion13,17-21

- Class II malocclusion with no mandibular crowding. The occlusion will finish in Class II molar and canine relation.

- Class I malocclusion with severe mandibular crowding or protrusion requiring mandibular extractions. The occlusion will finish in Class II canine relation and Class I molar relation.

b) Teeth Characteristics13,17-21

- Canines: smaller in size and with similar shade as central incisors, narrow at the CEJ level in both buco-lingual and mesio-distal dimensions, with a relatively flat labial surface.

- Premolar: similar in size as the canine.

c) Patient’s age13,17-21

- Younger patients, with increased growth potential.

- Adults whose occlusion and teeth characteristics are more favorable to this type of treatment (see A).

d) Apical position of the maxillary canine

- Maxillary canines with roots positioned mesially respond more favorably to canine substitution treatment.

e) Profile13,17-21

- A balanced profile in association with normally inclined maxillary incisors and minimal spaces in the maxillary dentition.

- Mildly convex profiles in association with maxillary anterior protrusion.

II) Important features to consider when doing canine substitution

a) Canine dimension13,18-20

- The greater labiolingual dimension of the maxillary canine can cause occlusal interferences with lower incisors, therefore an off-set in the canine is recommended. This can be achieved by adding a bend in the archwire or, by bonding the canine with a central incisor, canine or premolar bracket.

b) Position of the premolar in the canine area13,18-20

- Mesial rotation of the first premolar favours a better contact point and camouflages the premolars’ flat mesial surfaces. This can be achieved by bonding the bracket more distally or, by adding a mesial-in bend to the archwire.

c) Root torque13,18-20,22

- The root of the canine is thicker than that of the lateral incisor. To obtain more natural results the canine should receive additional lingual root torque. Conversely, the first premolar should receive more buccal root torque to simulate the canine eminence. Using a central incisor bracket is our preferred method to obtain ideal torque in the canine substituting a lateral incisor, using an inverted lower second premolar bracket can also achieve this result.

- For the premolars we recommend either bonding a maxillary canine bracket or placing torque to the archwire.

d) Leveling of gingival margins13,18-20

- In order to achieve the preferred “high-low-high” contour in the gingiva of the maxillary anterior teeth, extrusion of the maxillary canine and intrusion of the first premolar should be considered. This can be accomplished during initial bonding, repositioning of brackets during the finishing stage, and/or by adding intrusion/extrusion steps in the archwire . (Fig. 1)

e) Aesthetic Finishing of the anterior teeth is recommended13,18-20

- Canine as lateral incisor: reduction of the inciso-gingival and mesio-distal dimensions, with flattening of the labial surface, steepening of the lingual convexity, bleaching and reshaping the canine with composite bonding or veneers in the mesial-incisal area. (Fig. 1)

- Premolar as canine: increase in the mesio-distal and inciso-gingival dimensions, with restorative and periodontal procedures. Enameloplasty of the palatal cusp. (Fig. 1)

Fig. 1

ORTHODONTIC SPACE OPENING FOR SINGLE UNIT IMPLANT

I) Indications

a) Malocclusion11,15,16

- Class I malocclusion with adequate posterior intercuspation and generalized diastemas in the maxillary arch. (Fig. 2)

- Class III malocclusion

b) Teeth Characteristics11,16

- Incompatible sizes between central incisors, canines and premolars, significant shade discrepancy between central incisors and canines. (Fig. 2)

Fig. 2

c) Patient’s age11,24

- Preferably non growing patients. However, if this treatment alternative is to be initiated in a growing patient, consider delaying it with the anticipation of growth being completed by the end of orthodontic treatment.

II) Important features to consider during implant planning

a) Adequate crown space

- Maxillary lateral incisors width generally ranges from 5 to 7mm.7,10,11,17 There are basically three methods to determine the appropriate coronal space. (1) The dimensions of the contralateral tooth if present and appropriately sized, (2) treatment simulations (wax-up or digital). When the anterior and posterior teeth are optimally positioned in terms of function and aesthetics, the remaining space should be ideal for lateral incisor replacement.11 (3) As a rule of thumb, the clinical width of maxillary lateral incisors is similar to that of the mandibular canines.25

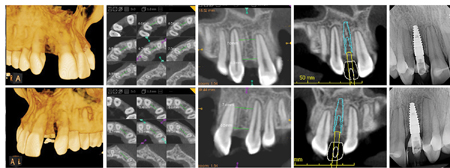

b) Adequate inter-radicular space

- When space is opened for a missing lateral incisor, the crowns of the maxillary central incisor and canines are tipped apart. The roots of these teeth do not move as quickly and often remain converged, possibly

obviating implant insertion. Therefore, additional attention and mechanics are important to make sure that the roots of the central incisor and canine are either parallel or slightly divergent.7,10,11,17,21,23,24 (Fig. 3) The root positioning must be evaluated prior to the removal of the orthodontic appliance through periapical radiographs,24 or CBCT. Communication with the surgeon is absolutely important at this time. - It is recommended that the distance between the head of the implant and the adjacent root be at least 1.5 mm to 2.0 mm,10,11 for preservation and proper development of the papilla.

- The ideal inter-radicular space should be at least 1mm1,26 to 1.5mm27 between the root and the implant. It bears noting that some patients with generally small teeth might be poor candidates for implant prosthesis due to current technological constraints i.e. implants are not as narrow as some naturally sized roots. In this situation an alternate restorative option could be considered.11

Fig. 3

c) Implant site development

- In the early mixed dentition, extracting the primary lateral incisor may encourage the permanent canine to erupt adjacent to the central incisor. This results in an increased buccolingual alveolar width in the lateral incisor area.11,24 (Fig. 4)

- Canine distal movement should be postponed for as long as possible, so that by the end of orthodontic treatment, patients are closer to skeletal maturity. This delay strategy will also reduce the chances of alveolar bone atrophy and root relapse/migration into the implant site.11,23,24,26 (Fig. 4)

Fig. 4

d) Determination of the ideal age for implant placement in growing patient

- In general, the average age for growth completion is 17 years for females and 21 years for males thus, implant placement could happen after this age.28 Nevertheless, these data represent a statistical average and are not suitable for any given patient.

- The most predictable method to monitor changes resulting from craniofacial growth is through superimposition of serial cephalometric

radiographs, taken with an interval of 6 months to 1 year. In the absence of significant changes, the implant can be installed.28 Alternatively, the patients’ height can be monitored.

II) Clinical tips on space opening

a) To overcome convergence of roots between central incisors and canines, the central incisor and canine brackets can be bonded with slight mesial root tip and distal root tip respectively.

b) Use a low torque prescription in the maxillary central incisors if the mechanical plan is to use coil springs to open the space. This may avoid additional proclination of central incisors and the associated “wagon wheel effect”, which results in root convergence.

c) Use of fixed retainers is strongly recommended to prevent post treatment apical migration into the implant site

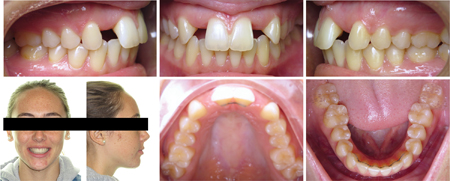

CASE 1

The patient presented for orthodontic retreatment at 18 years old. She had previously been treated with spaces opened for the missing lateral incisors. (Figs. 5,6) During retention phase she struggled to use the retainers and consequently there was root relapse towards the edentulous area. The insertion of implants was not possible due to inadequate inter-radicular root position, this problem was exacerbated by her particularly small teeth. (Figs. 5,6) After a second round of orthodontic treatment featuring interproximal enamel reduction of the maxillary teeth, adequate radicular space and root parallelism was achieved for the implant insertion. (Figs. 7,8) The patient had bone grafting, implant placement and an excellent result was obtained. (Fig. 9)

Fig. 5

Fig. 6

Fig. 7

Fig. 8

Fig. 9

When assessing her initial malocclusion, (Fig. 10) at 14 years, opening the spaces for the missing maxillary lateral incisors appeared to be the ideal treatment plan. Nevertheless, maintaining the permanent canines as lateral incisors and keeping the deciduous canines for a late implant substitution (as observed in clinical Case 2) could have been another great alternative. Especially considering the following: mesial crown, root position and morphologic characteristics of the maxillary canine, difficulty of canine root translation, treatment time, psychosocial implications for the patient and smaller surgical burdens.

Fig. 10

CASE 2

A 13-year-old female patient, presented a balanced facial profile with adequate maxillary incisor display, shallow overbite, minimum overjet and a Class I malocclusion complicated by missing maxillary lateral incisors. The maxillary permanent canines were erupted in the lateral incisor position and the deciduous canines were also present. Root parallelism between maxillary central incisors and canines is observed. (Figs. 11,12) In this case the maxillary permanent canines were maintained in the lateral incisor area, these teeth were extruded and reshaped to mimic lateral incisors. Despite the short roots, the deciduous canines were maintained for future implant substitution. (Fig.13) Both the patient and her family were thrilled with the aesthetic result, they appreciated that no pontics were required and that there was no immediate need for implants. In this case implant placement in the canine site can be delayed until exfoliation of the deciduous canines or to a time of financial and social convenience.

Fig. 11

Fig. 12

Fig. 13

To summarize, educating the patients about their condition, advantages and disadvantages of various treatment alternatives is essential to an informed decision and commitment to treatment. We encourage our colleagues to consider all treatment alternatives, not only from a clinical but also from a social perspective. Using pontics in an aesthetic region is an efficient mechanism for temporary replacement of a missing tooth, however, there is a social cost related that is often neglected. Many of these patients experience emergencies in which the pontics fail or fall off, generating embarrassment, anxiety, additional appointments and general frustration.

The authors concede personal bias on this topic, since we both have immediate relatives with agenesis of maxillary lateral incisors. We suggest that our fellow dental professionals seek a balance between the conventional approaches, their personal preferences, professional perfectionism and overall patient welfare. We should always be asking “what treatment approach would I want for my own relative?”

Oral Health welcomes this original article.

Acknowledgment: We would like to acknowledge Dr. Mario Rotella (prosthodontist), Dr. Monica Raina (periodontist), Dr. Paul Korne (orthodontist) and Dr. Amalia Moncada (Periodontist) for their contributions to the cases featured in this article.

References

- Chu, C.S.; Cheung, S.L.; Smales, R.J. Management of congenitally missing maxillary lateral incisors. General Dentistry: 1998;43(3):268-274.

- Vastardis, H. The genetics of human tooth agenesis: New discoveries for understanding dental anomalies. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop.: 2000;117(6):650-656.

- Macedo, A. et al. Treatment of patients with missing maxillary lateral incisors SPO: 2008;41(4)418-424.

- Polder B.J., Van’t Hof M.A., Van der Linden F.P.G.M., Kuijpers-Jagtman A.M. A meta-analysis of the prevalence of dental agenesis of permanent teeth. Community Dent. Oral. Epidemiol. 2004;32:217–226.

- Woodworth, D.A.; Sinclair, P.M.; Alexander, R.G. Bilateral congenital absence of maxillary lateral incisor: A craniofacial and dental cast analysis. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop.:1985;7(4):280-293.

- Dermaut, L.R.; Goeffers, K.R.; Smit, D. Prevalence of tooth agenesis correlated with jaw relationship and dental crowding. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop.:1986;90(3):204-210.

- Richardson, G.; Russel, K.A.; Congenitally missing maxillary lateral incisors and orthodontic treatment considerations for the single-tooth implant. Journal de l´Association Dentaire Canadienne: 2001;67(1):25-28.

- Bukhary, S.M.N. et al. The influence of varying maxillary lateral incisor dimensions on perceived smile aesthetics. British Dental Journal: 2007;203(12):687-693.

- Mcneill, R. W.; Joondeph, D. R. Congenitally absent maxillary lateral incisors: treatment planning considerations. Angle Orthod.: 1973;43(1):24-29.

- Kokich, V.O. Early Management of Congenitally Missing Teeth. Seminars in Orthodontics: 2005;11(3):146-151.

- Kinzer GA, Kokich VO Jr. Managing congenitally missing lateral incisors. Part III: single-tooth implants. J Esthet Restor Den: 2005;17:202-10.

- Kinzer GA, Kokich VO Jr. Managing congenitally missing lateral incisors. Part II: tooth-supported restorations. J Esthet Restor Dent: 2005;17:76-84.

- Kinzer GA, Kokich VO. Managing congenitally missing lateral incisors. Part I: canine substitution. J Esthet Restor Dent: 2005; 17:5-10.

- Robertsson S, Mohlin B. The congenitally missing upper lateral incisor. A retrospective study of orthodontic space closure versus restorative treatment. Eur J Orthod: 2000;22:697-710.

- Silveira GS, Mucha JN. Agenesis of Maxillary Lateral Incisors: Treatment Involves Much More Than Just Canine Guidance. Open Dent Journal:2016;29(10):19-27.

- Kokich, V.O. Maxillary Lateral Incisor Implants: The Orthodontic Perspective. Advanced Esthetics & Interdisciplinary Dentistry: 2006;2(2):2-7.

- Sabri, R. Management of missing maxillary lateral incisors. Journal of the American Dental Association: 1999;130(1):80-84.

- Rosa M, Zachrisson BU. Integrating esthetic dentistry and space closure in patients with missing maxillary lateral incisors. J Clin Orthod: 2001;35:221-34.

- Rosa M, Zachrisson BU. Integrating esthetic dentistry and space closure in patients with missing maxillary lateral incisors: further improvements. J Clin Orthod: 2007;41:563-73.

- Rosa M, Zachrisson Bu. The space-closure alternative for missing maxillary lateral incisors: an update. J Clin Orthod: 2010;44: 540-9.

- Thilander, B. Orthodontic space closure versus implant placement in subjects with missing teeth. Journal of Oral Rehabilitation: 2008; 35(1)64-71.

- Kravitz ND, Miller S, Prakash A, Eapen JC. Canine Bracket Guide for Substitution Cases. J Clin Orthod.: 2017;51(8):450-453.

- Thilander B, Odman J, Lekholm U. Orthodontic aspects of the use of oral implants in adolescents: a 10-year follow-up study. Eur J Orthod.: 2001;23(6):715-31.

- Beyer A, Tausche E, Boening K, Harzer W. Orthodontic space opening in patients with congenitally missing lateral incisors. Angle Orthod.: 2007;77(3):404-9.

- German DS, Chu SJ, Furlong ML, Patel A. Simplifying optimal tooth-size calculations and communications between practitioners. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2016;150(6):1051-1055.

- Olsen TM, Kokich VG Sr. Postorthodontic root approximation after opening space for maxillary lateral incisor implants. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop.: 2010;137(2):158-9.

- Randolph R. Ideal Implant Positioning, Misch’s Avoiding Complications in Oral Implantology, Mosby,2018;6:234-266.

- Fudalej P, Kokich VG, Leroux B. Determining the cessation of vertical growth of the craniofacial structures to facilitate placement of single-tooth implants. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop.: 2007;131(4 Suppl):59-67.

About the Author

Dr. Aura Sofia C. Manfi is in private practice in Scarborough, Ont. She can be reached at aurasofia.manfio@gmail.com.

Dr. Aura Sofia C. Manfi is in private practice in Scarborough, Ont. She can be reached at aurasofia.manfio@gmail.com.

Dr. Anthony Mair is a Clinical Instructor at The University of Toronto and Adjunct Professor at Western University. He has a private practice in Scarborough, Ont.

Dr. Anthony Mair is a Clinical Instructor at The University of Toronto and Adjunct Professor at Western University. He has a private practice in Scarborough, Ont.