Introduction

These are unprecedented times. The opioid crises strain our communities. The challenge for dental practitioners mirrors the need for new pathways. Being successful with patient treatment is imperative for all practicing dentists. Treatment success is determined by the outcome for the patient. Patients care primarily for levels of morbidity and only then for esthetics, function, and cost. Fear of pain during and after the procedure will deter a significant patient population from seeking dental care. Not until dental pain forces the patient to present as an emergency does the actual pain overcome the fear of pain.1,2

Post-operative pain (POP) in dental surgery is due to a surgical insult to the tissue and the subsequent inflammatory process.22

Prostaglandins and other inflammatory mediators, sensitize peripheral nerve endings and produce electrophysiological polarization effecting pain sensation.23 The initial insult causes a firing of fast speed myelinated A-delta fibers transmitting the pain signal to the central nervous system (CNS) for interpretation. Inflammatory pain then results from the activation of slow unmyelinated C-fibers and reaches its peak 48–72 h post-op.22 Pain modulation is complex because pain signaling pathways are affected by patient-specific physiological and psychological factors. Gender, age, predisposition to feeling pain, anxiety levels, and pain expectations influence pain levels for patients and their sensitivity to pain.24,25 Providers know from experience that patients’ pain perceptions even to local anesthetic injection varies greatly. On the face of it, this may be surprising because the procedure of local anesthetic administration is standardized by the provider, the injection technique and the medium injected. This implies that dosing and non-pharmacological techniques may also need to be modulated for effective control of POP in some cases.26

This paper will discuss the specific indications for post-operative pain management in dentistry. Presentation of single and combination options for pain management will be discussed.

Overview and definition of current Opioid Crisis with historical background

The American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons (AAOMS) recognized in 2017 that opioids are routinely prescribed for postoperative pain.19 They published the “White Paper on Opioid Prescribing: Acute and Postoperative Pain Management.” In it they stated that nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and Acetaminophen (APAP), taken simultaneously, work synergistically to rival opioids in their analgesic effect,” further recommending that opioids be reserved “only for acute, breakthrough pain”.20

Due to its highly addictive properties the use of opioids for pain management has come under attack. The chief clinical concerns associated with the widespread opioid and narcotics abuse epidemic is physical dependence and addiction, as well as serious adverse effects.27 While tolerance develops to the analgesic property of opioids, patients do not develop tolerance to their adverse effects. The prescriber may reduce the prescription dose to balance these unintended consequences, ultimately leading to inadequate analgesic effects.28

The American Dental Association recently announced a policy supporting statutory limits on opioid dosage and duration29 as a response to the urgent opioid epidemic. This has helped to encourage prescription and recommendations of non-opioid analgesics when clinically appropriate. However, there are also risks associated with oral NSAIDs, which may cause prolonged bleeding and gastrointestinal upset34,35,20 as they can impair platelet function and the coagulation cascade. NSAIDs are contraindicated for patients who have gastrointestinal ulcerations and/or erosive gastrointestinal diseases.30 NSAIDs also increase the risk for thrombotic events, such as stroke and heart attack, and the risk of these vascular events increases with the duration of NSAID use;30 NSAIDs should be used with caution in patients on blood pressure medications or with a history of cardiovascular disease.31 Short term post operative use of up to 3 days may reduce adverse event occurrence. Post operative pain and swelling following oral surgery procedures typically subside following the third post-operative day,32 so pain management is most critical for 3 days following surgery.

NSAIDs should be avoided in pregnant patients. Instead, Acetaminophen (APAP) alone is preferred, and brief treatment with opioid-APAP combinations may be considered.36,37

Literature review of available evidence-based pain management options and presentation of selective papers.

Practicing credible, clinically applicable, evidence-based dentistry is the objective. Translational, reliable, and reproducible applications leading to successful treatment outcomes is the goal. Before a professional implements a new procedure or change, the provider strives to ascertain whether this will result in improvement.7

Metanalysis reviews hold the highest level of evidence, yet most of them conclude correctly, that more research is needed. Expert opinion and clinical experience documented in case reports hold the lowest level of academic empiric evidence and are considered anecdotal.

In 2016, a study evaluating an OTC pain management protocol with NSAIDs, acetaminophen and StellaLife VEGA mouth rinse (stellalife.com) resulted in a three-fold reduction in opioid prescriptions.13

In another oral surgery study, antiseptic mouth rinses were compared in their post operative morbidity management and their cytotoxicity. The StellaLife VEGA rinse was found to be superior to chlorhexidine in efficacy and pain reduction as well as healing properties.17

Starting in June 2020, the largest oral surgery division at the US Navy Recruit Training Command implemented a standardized non-opioid postoperative pain regimen for all dentoalveolar surgical cases.21 It consisted of maximum doses of ibuprofen 800 mg q6h around the clock and acetaminophen taken concurrently 650 mg q6h around the clock for 48 h, starting within an hour after surgery as opposed to loading the patients up pre-operatively with ibuprofen. This helped to stay ahead of the pain but without the blood thinning effect of the ibuprofen increasing the post op bleeding risk. In patients with reported contraindications to taking either medication an alternative regimen consisting of Tramadol 50 mg q6h prn breakthrough pain was prescribed substituting the contraindicated medication in combination with the other. Ultram was so effectively combined with either ibuprofen or with acetaminophen. This pain management regiment has since been routinely and successfully implemented in other clinics with modifications to the maximum medication doses as appropriate given patient comorbidities.21

Options of alternative methods of pain control.

Many patients know Arnica as antiphlogistic (anti-inflammatory) and analgesic in herbal as well as homeopathic form.13,5,6

Homeopathy has been used as a treatment modality since the 1800s and evidence of its safety and efficacy has been documented extensively,8 yet it remains the most controversial treatment modality in the field of complementary medicine. The reasons for the polarized, at times hostile controversy are rooted in fear of the unknown, which is the greatest fear of all.9

Conclusion: Recommendation of pain management protocol to minimize opioid dependance in narcotic naïve patient population.

There are no national guidelines containing recommendations for dentists on how to prescribe analgesics. In the United States, an ADA statement reviews the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidance and encourages dentists to consider primary administration of NSAIDs. It advises dentists to check substance use history and PDMPs (Prescription Drug Monitoring System). As well, the ADA policy on opioids suggests limits on opioid dosage and duration to no more than 7 days for acute pain treatment (consistent with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines)38 and encourages continuing dental education on the prescription of opioids.28 Unfortunately, these statements provide no clinical practice guidelines.

NSAIDS have been routinely used in indicated cases of pain management. Their contraindications are in general GI, urogenital, and nephrotic conditions, as well as allergies and sensitivities to these drugs. Patients with these limitations have minimal options for post operative moderate to severe pain management.3,4

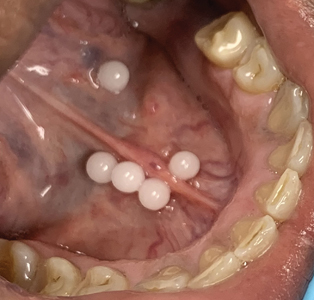

Some practitioners use, endorse, and promote pre- and post-operative intraoral topical homeopathic dilutions of Arnica montana with great and reproducible success.14 Current and classic research is providing evidence-based grounds for clinical application.8,12-17 Many seasoned practitioners utilize OTC available adjunctive oral and topical homeopathic analgesics and wound healing promoting agents like StellaLife (Figs. 1-3) and Arnica montana (Figs. 4-7).

Fig. 1

Fig. 2

Fig. 3

Fig. 4

Fig. 5

Fig. 6

Fig. 7

Evidence-based guidelines and curriculum interventions have been shown to shift health care provider behaviours.18 The implementation of an opioid prescribing guideline for dentists in Ontario led to a 25 pecent reduction in opioid prescribing volume.39 A 2020 survey of 172 dental residents concluded that changing the culture within the dental residency programs toward reducing the promotion of addiction may aid in reducing opioid overprescribing tendencies during residency training.40 Another 2021 survey of 586 dental students concluded that dental school curricula are effective targets for shaping the knowledge, attitudes, and prescribing behaviors of future dentists while reducing common misperceptions surrounding opioid misuse, abuse, and diversion.41,42

What is holding back progress, innovation and reduced post-operative patient morbidity is lack of education in unfamiliar concepts.18 That must change!

Oral Health welcomes this original article.

Acknowledgement: Samuel L Rabins, Research Assistant.

Disclaimer: Dr. Diana Bronstein has lectured and recorded webinars for Boiron®

References

- Bürklein, S., Brodowski, C., Fliegel, E., Jöhren, H. P., & Enkling, N. (2021). Recognizing and differentiating dental anxiety from dental phobia in adults: a systematic review based on the German guideline “Dental anxiety in adults.” Quintessence International, 52(4), 360–373. https://doi-org.ezproxylocal.library.nova.edu/10.3290/j.qi.a45603

- Sambuco, N., Costa, V. D., Lang, P. J., & Bradley, M. M. (2020). Assessing the role of the amygdala in fear of pain: Neural activation under threat of shock. Journal of Affective Disorders, 276, 1142–1148. https://doi-org.ezproxylocal.library.nova.edu/10.1016/j.jad.2020.07.110

- Sabounchi, S. S., Sabounchi, S. S., Cosler, L. E., & Atav, S. (2020). Opioid prescribing and misuse among dental patients in the US: a literature-based review. Quintessence International, 51(1), 64–76. https://doi-org.ezproxylocal.library.nova.edu/10.3290/j.qi.a43697

- Policy on Acute Pediatric Dental Pain Management. (2018). Pediatric Dentistry, 40(6), 101–103.

- Lennihan, B. (2017). Homeopathy for Pain Management. Alternative & Complementary Therapies, 23(5), 176–183. https://doi-org.ezproxylocal.library.nova.edu/10.1089/act.2017.29129.ble

- Bronstein, D. (2017). The Role of HOMEOPATHY In Oral Health Care. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene, 15(8), 55–58.

- Ciurczak FM, & Smith E. (1984). Dogmatism, age and change: a perspective of a nurse practitioner program. Journal of Nursing Education, 23(9), 374–379.

- https://homeopathyusa.org/uploads/Homeopathy-Research-Evidence-Base-09-01-2021.pdf

- Rusbatch V. (2000). Fear of the unknown. Vision (11749784), 6(10), 21.

- Schulz, H. (1888) “Uber Hefegiste”, Pflügers Archiv Gesammte Physiologie, Vol. 42 pp.517. Zur Lehre von der Arzneiwirkung. (1887) [Virchows] Archiv für pathologische Anatomie und Physiologie und für klinische Medizin, Berlin; 108: 423-445.

- A. Michtchenko; M. Hernandez (2006) Photobiostimulation Effects Caused for Low Level Laser Radiation with 650 nm in the Growth Stimulus of Biological Systems. Electrical and Electronics Engineering, 2006 3rd International Conference on Volume , Issue , Sept. Page(s):1 – 4

- Zhou P, Chrepa V, Karoussis I, Pikos MA and Kotsakis GA (2021) Cytocompatibility Properties of an Herbal Compound Solution Support In vitro Wound Healing. Front. Physiol. 12:653661. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2021.653661

- Tatch, W. (2019). Opioid prescribing can be reduced in oral and maxillofacial surgery practice. J. Oral Maxillofac Surg. 77, 1771–1775. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2019.03.009

- Muller, H. D., Eick, S., Moritz, A., Lussi, A., and Gruber, R. (2017). Cytotoxicity and antimicrobial activity of oral rinses in vitro. Biomed. Res. Int. 2017:40 19723.

- Lee, H. S., Yoon, H. Y., Kim, I. H., and Hwang, S. H. (2017). The effectiveness of postoperative intervention in patients after rhinoplasty: a meta-analysis. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol 274, 2685–2694. doi: 10.1007/s00405-017-4535-6

- Lee, C. Y., and Suzuki, J. B. (2019). The efficacy of preemptive analgesia using a non-opioid alternative therapy regimen on postoperative analgesia following block bone graft surgery of the mandible: a prospective pilot study in pain management in response to the opioid epidemic. Clin. J. Pharmacol. Pharmacother. 1:1006.

- Fujioka-Kobayashi, M., Schaller, B., Pikos, M. A., Sculean, A., and Miron, R. J. (2020). Cytotoxicity and gene expression changes of a novel homeopathic antiseptic oral rinse in comparison to chlorhexidine in gingival fibroblasts. Materials (Basel) 13:3190. doi: 10.3390/ma13143190

- Bronstein, D. (2016). Modifying Behavior to IMPROVE OUTCOMES. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene, 14(10), 45–49.

- Mutlu I, Abubaker AO, Laskin DM: Narcotic prescribing habits and other methods of pain control by oral and maxillofacial surgeons after impacted third molar removal. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2013; 71(9): 1500.

- American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. AAOMS Advocacy and Position Statements – White Papers: Opioid prescribing: Acute and Postoperative Pain Management. Available at https://www.aaoms.org/practice-resources/aaoms-advocacy-and-position-statements/whitepapers.

- Clarence Tang, DC, USN, James Buckley, DC, USN, Robert Burcal, DC, USN (Ret.), Opioid Prescription Reduction after Dentoalveolar Surgery—A Success Story in the Recruit Training Environment, Military Medicine, Volume 187, Issue 9-10, September-October 2022, Pages 261–263, https://doi-org.ezproxylocal.library.nova.edu/10.1093/milmed/usac103

- Bryce G, Bomfim DI, Bassi GS (2014) Pre- and post-operative management of dental implant placement. Part 1: management of post-operative pain. Br Dent J 217(3):123–127.

- Garg A (2011) Analgesia in implant dentistry. Dent Implantol Updat 22(6):41–45.

- Eli I, Schwartz-Arad D, Baht R, Ben-Tuvim H (2003) Effect of anxiety on the experience of pain in implant insertion. Clin Oral Implants Res 14(1):115–118.

- Beaudette JR, Fritz PC, Sullivan PJ, Piccini A, Ward WE (2018) Investigation of factors that influence pain experienced and the use of pain medication following periodontal surgery. J Clin Periodontol 45(5):578–585.

- Khouly, I., Braun, R. S., Ordway, M., Alrajhi, M., Fatima, S., Kiran, B., & Veitz-Keenan, A. (2021). Post-operative pain management in dental implant surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Clinical Oral Investigations, 25(5), 2511–2536. https://doi-org.ezproxylocal.library.nova.edu/10.1007/s00784-021-03859-y.

- Maxwell JC (2011) The prescription drug epidemic in the United States: a perfect storm. Drug Alcohol Rev 30(3):264–270

- Ricardo Buenaventura M, Adlaka MR, Sehgal MN (2008) Opioid complications and side effects. Pain Physician 11:S105–S120

- ADA, A.D.A (2018) Policy supports mandates on opioid prescribing and continuing education. Available from: https://www.ada. org/en/press-room/news-releases/2018-archives/march/American-dental-assoicaiton-announces-new-policy-to-combat-opioid epidemic. American Dental Association: Current policies: Substance use disorders (opioid crisis)

- Risser A, Donovan D, Heintzman J, Page T (2009) NSAID prescribing precautions. Am Fam Physician 80(12):1371–1378

- Trelle S, Reichenbach S, Wandel S, Hildebrand P, Tschannen B, Villiger PM, Egger M, Juni P (2011) Cardiovascular safety of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: network meta-analysis. Bmj 342:c7086

- Urban T, Wenzel A (2010) Discomfort experienced after immediate implant placement associated with three different regenerative techniques. Clin Oral Implants Res 21(11):1271–1277

- Bahammam MA, Kayal RA, Alasmari DS, Attia MS, Bahammam LA, Hassan MH, Alzoman HA, Almas K, Steffens JP (2017) Comparison between dexamethasone and ibuprofen for postoperative pain prevention and control after surgical implant placement: a double-masked, parallel-group, placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial. J Periodontol 88(1):69–77.

- Alissa R, Sakka S, Oliver R, Horner K, Esposito M, Worthington HV, Coulthard P (2009) Influence of ibuprofen on bone healing around dental implants: a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled clinical study. Eur J Oral Implantol 2(3):185–199

- Raja Rajeswari, S., Gowda, T.M., Kumar, T.A., Mehta, D.S., & Arya, K. (2017). Analgesic efficacy and safety of transdermal and oral diclofenac in postoperative pain management following dental implant placement. General dentistry, 65 4, 69-74 .

- G.G. Briggs, R.K. Freeman, S.J. Yaffe. Drugs in Pregnancy and Lactation: A Reference Guide to Fetal and Neonatal Risk. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins (2012)

- A. Kellogg, C.H. Rose, R.H. Harms, W.J. Watson. Current trends in narcotic use in pregnancy and neonatal outcomes. Obstet Gynecol, 204 (3) (2011), pp. 259.e1-259.e4.

- D. Dowell, T.M. Haegerich, R. Chou. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain: United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep, 65 (2016), pp. 1-49.

- Q. Guan, T. Campbell, D. Martins, et al. Assessing the impact of an opioid prescribing guideline for dentists in Ontario, Canada. JADA, 151 (1) (2020), pp. 43-50

- M. Shemkus, Y. Zhao, P. Mehra, R. Figueroa. Opioid prescribing patterns of oral and maxillofacial surgery residents. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol, 129 (3) (2020), pp. 184-191

- P.C. Tompach. A dental school survey assessing dental student knowledge, attitudes and prescribing behavior regarding opioid use and abuse. J Dental Sci Res Rep, 3 (1) (2021), pp. 5-6.

- Matthew J. Heron, Nkechi A. Nwokorie, Bonnie O’Connor, Ronald S. Brown, Adriane Fugh-Berman. Survey of opioid prescribing among dentists indicates need for more effective education regarding pain management. The Journal of the American Dental Association. Volume 153, Issue 2, 2022, Pages 110-119, ISSN 0002-8177, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adaj.2021.07.018.

About the Author

Dr. Bronstein is Diplomate of the American Board of Periodontology and Implant Dentistry and Diplomate and Fellow of the International Congress of Oral Implantologists with Specialty Certification in Periodontology and Oral Implantology and Master degrees in Oral Biology, Medical Education and Health Law. She has been Clinical Professor and a practicing dentist for over 22 years.

Dr. Bronstein is Diplomate of the American Board of Periodontology and Implant Dentistry and Diplomate and Fellow of the International Congress of Oral Implantologists with Specialty Certification in Periodontology and Oral Implantology and Master degrees in Oral Biology, Medical Education and Health Law. She has been Clinical Professor and a practicing dentist for over 22 years.

Dr. Suzuki has been Dean, and Professor of multiple universities, Diplomate and Fellow of various specialty boards as well as their past president and board examiner. He has published over 250 papers, chapters, and symposia, 200 abstracts and one textbook in Medical Technology.

Dr. Suzuki has been Dean, and Professor of multiple universities, Diplomate and Fellow of various specialty boards as well as their past president and board examiner. He has published over 250 papers, chapters, and symposia, 200 abstracts and one textbook in Medical Technology.