To view figures, click on figure mentions throughout the article.

Too often teeth are extracted merely due to the presence of apical periodontitis. The size of the apical radiolucency is not an indication for tooth extraction. Bacteria play the main role in the development of apical periodontitis. 1 Apical radiolucency is the result of enzymes released by polymorphonuclear neutrophil leukocytes (PMNs) and macrophages in a response to the exotoxins present in the root canal system. In the study by Fish, 2 he recognized 4 zones of response to pathogens present in the root canal system in order to isolate and localize an infection in the periradicular area. The zones of Fish are 1) Infection/Necrosis containing bacteria and polymorphonuclear neutrophil leukocytes, 2) Contamination containing bacterial toxins and macrophages, 3) Irritation containing osteoclasts and plasma cells and, 4) Stimulation containing osteoblasts and fibrobalsts. In his study, Fish demonstrates that the outer most layer of the granuloma which radiographically is observed in the form of an apical radiolucency is free of bacteria and is infiltrated by fibroblasts and osteoblasts. In most instances, the apical bone loss is as a direct result of PMNs, macrophages and osteoclast activation in response to pulpal necrosis. In these cases, non-surgical endodontic treatment has a good outcome and surgery is not needed (Figs. 1-3).

In contrast to Fish’s findings it was shown that bacteria were not confined and were able to invade bone and cause osteomyelitis. 3 Some studies suggest that periapical lesions are completely or partially contaminated with bacteria. 4,5 If the clinician has over instrumented the canal beyond 2 mm of the apical foramen and infected dentin has been pushed out beyond the apical terminus, then it raises the incidence of bacteremia and post-operative flare ups. 6,7

Fig. 1A

Pretreatment image of upper maxillary lateral incisor

Fig. 1B

Post-treatment image.

Fig. 1C

Two years post-op image.

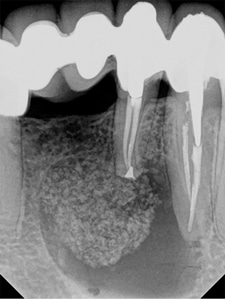

Fig. 2A

Pre-treatment image of lower madibular first molar.

Fig. 2B

Post-treatment image. Orifices were sealed with amalgam. Occlusal surface composite was placed.

Fig. 2C

Six months post-treatment image. Healing progressing but incomplete

Fig. 2D

Eighteen months post-treatment image. Healing has completed.

Fig. 3A

Pre-treatment image of lower first premolar.

Fig. 3B

Post-treatment image. Post space was provided in the lingual canal.

Fig. 3C

One-year post-treatment image.

The power of healing is the most powerful tool we have and mainly thanks to the excellent blood supply in the face. This is well recognized by plastic surgeons, and this is why they can perform so many facial cosmetic procedures with a satisfactory result. Yet, we dentists panic once we see an apical radiolucency and we forget about our best weapon, the immune system and we rush into opening up our implant kit. The inflammatory response to the presence of bacteria in the root canal system will reverse once the pathogen is removed by non-surgical or surgical endodontic treatment. Osteoclasts will be replaced by osteoblasts and bone will start to form. Initially the fastest growing cells tend to migrate to the site. Periodontal lesions heal from the periphery towards the zone of infection or the root apex. Boyne and Harvey in their study concluded that in the presence of a cortical bone defect measuring 9 to 12 mm, avascular fibrous tissue had filled up the bony defect in the first 8 months following the surgery. Initially the fast growing periodontal ligament, lamina propria of the gingiva and the epithelial cells tend to migrate to the site and later slow growing cells of the alveolar bone. 8

Case Report: Combination of Non- and Surgical Endodontic Treatment

A female patient was referred for treatment of teeth #32 & #33. She was complaining of pressure sensitivity. Pulp test was negative and the palpation test was positive. Due to the size of the apical radiolucency she was initially scheduled by her implant trained family dentist to remove the bridge, extract #32 and (possibly #33) and place implants. Option to consult with an endodontist was not given. She was referred to us by a different dentist for a second opinion. Radiographically a large periapical and lateral radiolucency was visible (Fig. 4A).

After discussing alternative options, we opted for endodontic treatment followed by periapical surgery. A large periapical lesion in this size will not heal just by endodontic treatment.

Fig. 4A

Pre-treatment image of teeth #32 & #33. Bridge extending from #33 and #43. Teeth #42 and #41 are missing.

First Appointment: Non-Surgical Endodontic Treatment

No anesthetic was given. Pulp was necrotic and bone was not in the proximity of the root end.

Access was made through the crowns. The canals were instrumented with a combination of K-files and later rotary memory shaped files. Most of the instrumentation was done with hand files. Both teeth had 2 canals. Each canal had to be enlarged to size #15/02 prior to placing a rotary file to avoid file separation. Chemical cleaning was completed with irrigating the canals with 6% sodium hypochlorite delivering the solution with Naviflex (Clinical Research) 31-gauge needle 3 mm short of the radiographic working length. A total volume of 10ml sodium hypochlorite followed by 3ml of Qmix (Dentsply Sirona) was used. Canals were filled with gutta percha and post space was provided in tooth #33. Access was closed with IRM and the patient was referred back to the referring dentist to have the access closed prior to performing the surgery to avoid coronal leakage (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4B

#33 & #32 post-treatment image after obturation. #33 post space was provided.

Second Appointment: Surgical Endodontic Treatment

The access was closed by the referring dentist. Lower jaw IAN block was given by administering Lidocaine HCl 2% epinephrine 1:100,000. Infiltration lidocaine HCl 2% epinephrine 1:50000 distal to the lesion was placed to control hemostasis, waiting 10 to 15 minutes for the epinephrine to constrict the blood vessels in the soft tissue. In female patients, Lidocaine is preferred because it is the safest and falls into category B drugs in case the patient is a few weeks pregnant and is unaware of it.

Full thickness triangular shaped flap was reflected. Buccal cortical bone was missing and was measured greater than 12mm (Fig. 4C). Number 32 apicoectomy was performed under the microscope (Fig. 4D). Microsurgical root-end preparation was done with ultrasonic diamond coated tips. The mode of action in ultrasonic unit used in endodontic surgery is different than the ultrasonic unit used in periodontics. Root end filling material ProRoot MTA (Dentsply Sirona) was placed.

Bone grafts in periapical surgery have shown better healing in comparison to a non-grafted site. 9,10 There are four types of bone grafts: 1) Autograft, bone graft from the same individual, 2) Allograft, bone grafted from a different individual, 3) Alloplast, is a synthetic bone graf, and 4) Xenograft, bone from a species other than human.

Allograft bone was preferred because 1) No additional surgery is required (unlike Autograft), 2) Same species (unlike Alloplast and Xenograft), 3) Some Osteoinductive properties (unlike Alloplast and Xenograft). Allograft mineralized ground cortical size 0.5CC was used (Straumann). Cortical bone was used versus trabeculae bone. Cortical bone is much denser. It delays resorption, preventing the ridge from collapsing and is more radiopaque. The bony defect was not completely filled with the allograft bone (Fig. 4E). Because there is a hole, it should not be completely filled out. The host blood will provide the best natural healing. A space was left to be filled with coagulation to act as a scaffold between the healthy bone, and grafted bone, to transfer the remodeling cells.

No membrane barrier was used. The use of membrane in periapical surgery, where only buccal cortical bone was missing, has shown no benefit. 11 Tissues were stabilized with resorbable chromic gut #5 sutures using a combination of sling and interrupted suturing techniques.

Fig. 4C

Large buccal bony defect greater than 12 mm.

Fig. 4D

#32 post-op image after apicoectomy was performed and root end MTA filling was placed.

Fid. 4E

Post-treatment image. Allograft bone surrounded by host blood.

Recall

The patient was seen for one (Fig. 4F) and three year recall (Fig. 4G). Periapical radiolucency had completely healed. Clinically, there was excellent soft tissue adaptation (Fig. 4H) and a CBCT was taken. Buccal cortical bone was in the same bucco-lingual dimension in the surgical site as in the non-surgical dentulous site (Fig. 4I).

Fig. 4F

One-year post-treatment image.

Fig. 4G

Three years post-treatment image.

Fig. 4H

Three years post-treatment intra oral image. Excellent soft tissue adaptation.

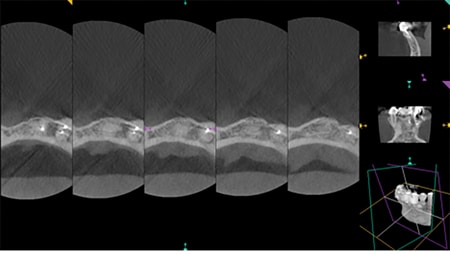

Fig. 4I

Three years post-treatment CBCT image. Well-filled buccal cortical bone.

Conclusion

In the absence of a root fracture and uncontrolled periodontal involvement (non-endodontic in origin), two questions should be asked by the clinician prior to deciding to extract the tooth: 1) Would we be able to eradicate the bacteria by non-surgical and/or surgical endodontic treatment? 2) Would we be able to maintain the coronal seal? If your answer is “yes” to both of these questions, endodontic treatment is the best choice regardless of the size of the apical radiolucency.

In Summary

The indication for a tooth extraction should be based on a lack of coronal tooth structure to restore the tooth, the presence of a vertical root fracture and an uncontrolled periodontal lesion without having an endodontic origin.

When the periapical lesion has been infiltrated with bacteria, non-surgical endodontic treatment will most likely not resolve the lesion. This is important to understand as that is why some endodontic cases, though shaped and filled well to radiographic working length, still end up failing. Surgical treatment will be needed in these cases to address the bacterial invasion beyond the periapical foramen. The good news is that most periapical lesions are not invaded with bacteria and when non-surgical endodontic treatment is performed optimally, it should heal the apical pathosis. OH

Oral Health welcomes this original article.

References

- Kakehashi S, Stanley HR, Fitzgerald RJ (1965). The effects of surgical exposures dental pulps in germ-free and conventional laboratory rats. Oral Surgery Oral Medicine and Oral Pathology 20:340-9.

- Fish EW. Bone infection. J Am Dent Assoc 1939;26(5):691-712.

- Simon J, Hemple R, Rotstein I, Salter P. Role of virulence in periapical lesions. Endodontology, Vol. 11, 1999.

- Found AF et al. Healing of induced periapical lesions in ferret canines. J. Endod 1993;19:123.

- Tronstad L et al. Extra radicular endodontic infections. Endod Dent Traumatol 1987;3:86-90.

- Bender IB, Seltzer S, Yermish M. The incidence of bactermia in endodontic manipulation. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 1960;13(3):353-60.

- Savarrio L, Mackenzie D, Riggio M, et al. Detection of bacteraemias during non-surgical root canal treatment. J Dent 2005;33:293-303.

- Melcher AH. On the repair potential of periodontal tissues. J Periodontal 1976;47:256-60.

- Pinto V, Zuolo M, Melloning J. Guided bone regeneration in the treatment of a large periapical lesion: a case report. Pract Periodontic Aesthe Dent 1995;7:76-82.

- Demiralp B, Kecali H, Muhtarogullari M, Serperr A, Demiralp B, Eratalay K. Treatment of periapical inflammatory lesion with the combination of platelet rich plasma and tricalcium phosphate: a case report. J Endod 2004;30:796-800.

- Garrett K, Kerr M, Hartwell G, O’Sullivan S, Mayer P. The effect of a biorestorable matrix barrier in endodontic surgery on the rate or periapical healing: an in vivo study. J Endod 2002;28:503-6.

About the Author

Dr. Houman Abtin completed his graduate endodontic training from UBC. He is in private practice in West Vancouver, BC. He is a clinical assistant professor at the University of British Columbia. He is a founder of Pacific Endodontics Hands-On Courses. Dr. Abtin can be reached at www.rootcanalspecialist.ca

Dr. Houman Abtin completed his graduate endodontic training from UBC. He is in private practice in West Vancouver, BC. He is a clinical assistant professor at the University of British Columbia. He is a founder of Pacific Endodontics Hands-On Courses. Dr. Abtin can be reached at www.rootcanalspecialist.ca