Introduction

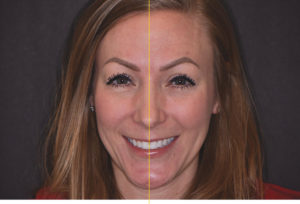

When it comes to re-creating a patient’s smile, it is not as simple as placing veneers or crowns on teeth that are whiter and brighter than the patient’s existing dentition (Figs. 1 & 2). The smile is an important reflection of one’s self along with communicating a variety of emotions to those around us and it is unique to each individual person. In fact, there are many factors that must be carefully considered and evaluated in creating a smile that is esthetically pleasing to the doctor and the patient. And even with digital technology having a widespread effect on so many things, including restorative dentistry, as well as allowing for digital simulations of a patient’s final smile, there are many factors1 and principles2 that must be evaluated by the treating doctor. Creating an ideal smile may require orthodontics, orthognathic surgery, periodontal surgery, cosmetic dentistry, oral surgery, and plastic surgery. Likewise, it cannot be stressed enough that if indirect restorations will be a part of the final treatment plan, involving the dental technician that will be doing the final restorations, should be consulted early in the process as they can bring an invaluable component to helping the clinician and patient achieve the desired final result.

Fig. 1

Fig. 2

In this article, we will provide a broad overview, but not all encompassing, of the multitude of factors and principles that a clinician must consider when a patient presents to their clinic for changes and overall enhancement of his or her smile.

Patients Desires and Expectations

One of the most important parts that must be considered before any treatment is begun is the clinician must take the time to discuss and discover the patient’s chief complaint and concerns and whether he or she can achieve or succeed the patient’s desired final result. After a thorough review of the patient’s medical and dental history, a comprehensive dental examination is completed, including proper radiographs, evaluation of the muscles and temporomandibular joint (TMJ). When it comes to restorative dentistry that involves significant dental treatment, including the patients smile, it is essential to have proper documentation to a achieve proper diagnosis. This will include proper photos that are taken with a digital SLR camera with a macro lens (Fig. 3) that include: full face photos (Fig. 4); 1:2 lip at rest or repose photos (Fig. 5); anterior and lateral photos (Figs. 6-8) and/or video of the patient smiling naturally, dynamically as well as an exaggerated smile; 1:2 retracted anterior and lateral views (Figs. 9-11); retracted views occlusally (Figs. 12-13); 1:1 retracted views of the anterior dentition (Figs. 14-16). The clinician should also obtain impressions (whether digital or analog) as well as a facebow and a bite registration in CR (centric relation), so that the case can be properly mounted and articulated on a semiadjustable articulator (Fig. 17). All of this critical information for the clinician to properly evaluate, review, treatment plan and thus, treat the patient appropriately and effectively.

Fig. 3

Fig. 4

Fig. 5

Fig. 6

Fig. 7

Fig. 8

Fig. 9

Fig. 10

Fig. 11

Fig. 12

Fig. 13

Fig. 14

Fig. 15

Fig. 16

Fig. 17

After a thorough assessment, it is critical to review treatment options and expected outcomes with the patient in order for the patient to make an informed decision about treatment choices. This allows for the patient to give input on any compromises in the final outcome should he/she decide to choose less than ideal treatment, and consequently, accepting any result that is less than desired due to such decisions.

Facial Aesthetics

A basic overall assessment of the smile must start from an outside-in approach and thus, there has to be some evaluation of the patient’s overall facial features, including facial proportions and evaluation of the facial esthetics in the vertical and horizontal planes. Assessment of the patient’s facial thirds and whether there are any disproportions present between the superior, middle and lower thirds (Fig. 18). It is important to look for asymmetries in the facial features starting from the facial midline and how it intersects with the dental midline. It is important to assess asymmetries from the right and left hemifacial portions as well assessment of the patient’s interpupillary line and occlusal planes as well as the relation to the horizon (Fig. 19). Notable concerns in these areas can be an indication of skeletal or growth and development issues that may or may not have an impact on the patients’ smile. A good example is a patient who may have a concern over an excessively gummy smile, when in fact, it may be due to the fact the patient has an excessively long middle third of the face and longer facial height, indicating vertical maxillary excess (VME). Vertical maxillary excess is a skeletal issue, and hence, would require a different treatment modality to successfully treat the patient’s concern.

Fig. 18

Fig. 19

Upper Lip Length, Lip Position, Mobility and Symmetry

The lips play an important role as they create the boundaries of the smile and play an important role in the complete smile design. Overall lip mobility is simply the movement of the lips at rest to the farthest position that occurs when the patient smiles spontaneously and is directly related to the upper lip length.4 In order to do so, assessment of the upper lip length (Figs. 20-21) and amount of tooth that is displayed at rest must be first assessed and then reassessment at the farthest position. The average upper lip length in males is 23 mm and 20mm in females, who have an average of 1.5 mm of higher lip line, and thus showing more tooth display at rest. The average lip mobility in general is 7-8 mm, with females (Fig. 22) having slightly more lip elevation than males (Fig. 23), and in turn, show more tooth display during smiling. Overall symmetry of the patient’s lip mobility must be assessed as well since there is a significant portion of the patient population (8.7-22%)5,6 that has asymmetry (Fig. 24) of the movement of upper and lower lips upon smiling and at rest. This can lead to more tooth and/ or gum displayed on one side versus the other, creating a disharmony in the overall smile of the patient. It is important for the clinician to take a series of photos and/or the use of video to assess the patient’s overall lip mobility and position in relation to the overall tooth display to gain an accurate assessment of the position of the teeth and gums to the lip position.

Fig. 20

Fig. 21

Fig. 22

Fig. 23

Fig. 24

Tooth Display

The amount of tooth that is displayed at rest is greater in females than males by an average of 1.5mm.7 The average 30-year-old female displays 3.5 mm of maxillary central incisors at rest versus 1.9mm in males and as patients age, they display less of the maxillary incisors (1-1.5 mm in females at age 50; 0-0.5 mm in females at age 70 and more mandibular incisors. This is a result of changes in soft tissues to the skeletal base. There is a significant gender difference8 in gingival display upon smiling where females tend to show more gingiva than males.

Incisal Edge Position in Relation to Surrounding Tissues and Horizontal Planes

The incisal edge position must also be evaluated in relation to the surrounding tissues as well. One landmark to evaluate is the interpupillary line and how the incisal edge is in relation to it. Consideration should be taken of how the incisal edge position relates to the interpupillary line in a parallel plane (Fig. 25). It has been shown that there is a significant correlation between the maxillary incisal edge position and the interpupillary line.9 The incisal edge position should be assessed in relation to the occlusal plane and posterior teeth and the incisal edge in relation to the lower lip/wet dry line or smile line.

Fig. 25

Another consideration is the relationship of the tooth position and what is considered the “buccal corridor”. The buccal corridor is the space that is present between the lateral aspects of the posterior teeth and the corner of the mouth. When there is “dark” space in the buccal corridor, this is considered a “negative space” (Fig. 26). It has been suggested16 that having minimum “negative space” in buccal corridors is preferred esthetically.

Fig. 26

Midline

The position of the teeth, and the dental midline in regard to the facial midline and surrounding tissue is another area that has to be assessed during the smile evaluation (Fig. 27). It is important to evaluate the relationship of the dental midline to the facial midline in addition to the overall angulation of the midline. Studies10 show that most people, including dental professionals will be unable to detect up to a 4 mm dental midline deviation from the facial midline. However, when there are slight changes in crown and midline angulation, it becomes quickly evident to most people. Hence, overall angulation of the midline is more critical than the overall position of the midline to create an esthetically pleasing smile.

Fig. 27

Current Tooth Position Within Dentoalveolar Housing

Overall current tooth position in the dentoalveolar housing is another important consideration when it comes to developing an ideal new smile. Without proper evaluation, this can lead to the clinician attempting to obtain ideal results unsuccessfully when the tooth and/or root position and angulation are in the improper position. Ideally, tooth position should be assessed in three dimensionally so that the following can be evaluated properly:

Facial-Lingual Position

Mesial-Distal Position

Apical-Coronal Position

Each of these components should be assessed and the following questions should be considered:

- Is the tooth tipped or bodily positioned in relation to the adjacent tooth or teeth, roots, arch form, and the interaction with the opposing arch, lips and surrounding tissues?

- Is the current position and balance between the “white” (tooth) and “pink” (gingival architecture) esthetics visually pleasing to the eye?

- Will the current position compromise the final desired result? If so, can it be managed restoratively alone or will it require repositioning of the tooth, root and/or surrounding tissues with the assistance of orthodontics, orthognathic surgery, periodontal surgery or a combination?

- If managed by restorative options alone, will this lead to aggressive tooth reduction that may compromise the longterm health of the patient’s dentition and/or will it create less than ideal final restorations? (i.e. a tooth that is lingually inclined and the final restoration is too thick facially)

- If current tooth position compromises the outcome and/or long-term tooth health, has this been communicated to the patient when he or she is unwilling or unable to commit to a more ideal treatment plan?

Facial-Lingual Position

Preferably, the facial lingual position should allow the tooth to be in a position that allows for the desired end result in a minimally invasive way. Teeth (Figs. 28 & 29) that are proclined or retroclined can have a direct impact on the restoration and/or the final desired result and thus, the clinician must assess this as well.

Fig. 28

Fig. 29

Mesial-Distal Position

When assessing current long axis tooth position, and to create an ideal smile, we would like to see the long axis of the teeth be parallel between the two centrals, and a slight mesial inclination in the laterals and even more mesial inclination of the canines toward the midline (Fig. 30). Variation in the inclination of the teeth in a mesial/distal aspect has been shown10 to be a factor that can quickly be visually detected by most people and can be interpreted as unaesthetic.

Fig. 30

Apical-Coronal Position

The apical-coronal position of teeth in relation to the adjacent teeth, as well as the full smile, smile in repose is critical to creating an esthetically pleasing smile. If the patient’s lip line exposes the gingival architecture, then it is vital to assess gingival heights and zeniths as well as overall symmetry and proportion to the contralateral side. If this is not the case, this creates asymmetry and disharmony (Fig. 31). The apical-coronal position of the teeth is one aspect that impacts the overall papilla position and overall contact heights, which should be approximately 50 (papilla) :50 (contact length). Obviously, the patients overall periodontal health should be assessed and how it impacts the relationship of the gingival architecture to the current tooth position as well as current papilla position.

Fig. 31

Tooth Proportions and Proper Length to Width Rations

Overall tooth proportions are another key and critically important assessment that must be made by the clinician during the initial evaluation. The average length of the maxillary central incisor is 10.5-11 mm and average width to be 8.0-9.0 mm, creating an average length to width ratio of approximately 76%. It has been discussed11,12 and suggested that overall assessment of the length to width ratios can be related to the “golden proportions”, a term that related back to ancient Greeks who used the term to related the proportions between large and small in the beauty of nature. However, this has been refuted in studies and Chu13,14 showed a significant correlation between the widths of the centrals, lateral and canines. Dentists can easily determine the overall width of the maxillary teeth by allowing the width of the maxillary centrals to be “Y”, the width of the lateral to be “Y – 2 mm”, and the width of the canine to be “Y – 1 mm”. Completing a simply overlay of ideal tooth proportions can be quickly and easily done to assess length to width ratios (Fig. 32).

Fig. 32

Anterior Guidance and Coupling

An equally important, and sometimes overlooked principle when it comes to smile design, is the importance of function following form and how the anterior teeth couple together and help guide the posterior teeth apart. Ideally, canine guidance with immediate posterior disclusion is desired as this has been shown to decrease overall elevator muscle activity.15

Other Factors to Consider – Microesthetics

When it comes to designing the ideal smile for our patients, especially with the use of indirect restorations, the clinician needs to assess and discuss the final color or shade desired by the patient. If possible, a shade that is naturally pleasing but esthetically enhancing to the patient’s final desired result is best. The restorative dentist should also communicate to the his or her lab technician about desired facial surface texture, overall incisal translucency, additional tooth characteristics including incisal effects, embrasures, tooth shape, and variations in value, hue and chroma from the centrals to the cuspids (Fig. 33).

Fig. 33

Summary

This article serves as a brief summary of smile design along with the multitude of assessments and evaluation in order to obtain an ideal smile for our patients that may include interdisciplinary care. It is critical for the practitioner to have experience, education and background in evaluating, treatment planning and treatment sequencing in a variety of areas in order to effectively manage, refer and treat patients that have concerns with his or her smile.

Oral Health welcomes this original article.

References

- Davis NC. Smile Design. Dent Clin North Am. 2007 Apr;51(2):299-318, vii.

- Bhuvaneswaran M. Principles of smile design. J Conserv Dent. 2010 Oct;13(4):225-32. doi: 10.4103/09720707.73387.

- Benson, Kenneth & Laskin, Daniel. (2001). Upper lip asymmetry in adults during smiling. Journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery : official journal of the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. 59. 396-8. 10.1053/joms.2001.21874.

- Roe, Phillip & Runcharassaeng, Kitichai & Kan, Joseph & Patel, Rishi & Campagni, Wayne & Brudvik, James. (2012). The Influence of Upper Lip Length and Lip Mobility on Maxillary Incisal Exposure. The American Journal of Esthetic Dentistry. 2. 116-125.

- Mathis, Andrew & Laskin, Daniel & Tufekci, Eser & Caricco, Caroline & Lindauer, Steven. (2018). Upper Lip Asymmetry During Smiling: An Analysis Using Three-Dimensional Images. Turkish Journal of Orthodontics. 31. 32-36. 10.5152/ TurkJOrthod.2018.17056.

- Laskin DM. Upper lip asymmetry in adults during smiling. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001 Apr;59(4):396-8.

- Vig RG, Brundo Gc. The Kinetics of anterior tooth display. J Prosthet Dent. 1978:39; 502-504.

- Al-Habahbeh R, Al-Shammout R, Al-Jabrah O, Al-Omari F. The effect of gender on tooth and gingival display in the anterior region at rest and during smiling. EurJ Esthet Dent. 2009 Winter;4(4):382-95.

- Malafaia FM, Garbossa MF, Neves AC, DA Silva-Concílio LR, Neisser MP. Concurrence between interpupillary line and tangent to the incisal edge of the upper central incisor teeth. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2009;21(5):318-22. doi:1111/j.17088240.2009.00283.x.

- Kokich VO Jr, Kiyak HA, Shapiro PA. Comparing the perception of dentists and lay people to altered dental esthetics. J Esthet Dent. 1999;11(6):311-24.

- Levin EI. Dental esthetics and the golden proportion. J Prosthet Dent 1978;40:244-52.

- Lombardi RA. The principles of visual perception and their clinical application to denture esthetics. J Prosthet Dent 1973;29: 358-82.

- Chu SJ. Range and mean distribution frequency of individual tooth width of the maxillary anterior dentition. Pract Proced Aesthet Dent. 2007 May;19(4):209-15.

- German DS, Chu SJ, Furlong ML, Patel A. Simplifying optimal tooth-size calculations and communications between practitioners. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2016 Dec;150(6): 1051-1055. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo. 2016.04.031.

- Manns A, Chan C, Miralles R. Influence of group function and canine guidance on electromyographic activity of elevator muscles. J Prosthet Dent. 1987

- Moore T, Southard KA, Casko JS, Qian F, Southard TE. Buccal corridors and smile esthetics. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2005 Feb;127(2):208-13; quiz 261.

About the Author

Jeffrey W. Lineberry currently lives in Mooresville, North Carolina and owns and operates Carolina Center for Comprehensive Dentistry, a fulltime complex restorative focused practice. Dr. Lineberry received his Bachelor of Science in Biology from Western Carolina University and his Doctor of Dental Surgery degree from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 2000. He has obtained his Fellowship in the Academy of General Dentistry and in the International Congress of Oral Implantologists. He currently serves as a Visiting Faculty member, Online Moderator and contributing author for Spear education, a leader in continuing dental education. He is also a Faculty Assistant at the Pankey Institute. He is an Accredited by the American Academy of Cosmetic Dentistry (AACD) and is a member of the AAID and American Equilibration Society.

Jeffrey W. Lineberry currently lives in Mooresville, North Carolina and owns and operates Carolina Center for Comprehensive Dentistry, a fulltime complex restorative focused practice. Dr. Lineberry received his Bachelor of Science in Biology from Western Carolina University and his Doctor of Dental Surgery degree from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 2000. He has obtained his Fellowship in the Academy of General Dentistry and in the International Congress of Oral Implantologists. He currently serves as a Visiting Faculty member, Online Moderator and contributing author for Spear education, a leader in continuing dental education. He is also a Faculty Assistant at the Pankey Institute. He is an Accredited by the American Academy of Cosmetic Dentistry (AACD) and is a member of the AAID and American Equilibration Society.

RELATED ARTICLE: The Use of Digital Smile Design for Everyday Dentistry