Abstract

Patients present to us dental professionals with complex restorative problems seeking our help. These problems often do not have straight forward solutions. A seemingly innocuous restoration such as a crown is often complicated by problems such as inadequate tooth structure, the pulpal and periodontal status of the tooth, the position of the tooth in the arch relative to the position and status of the remaining teeth and possibly the occlusal plane.

The sequence in providing treatment options involves an adequate assessment of the oral condition based on the patient’s symptoms, followed by a comprehensive evaluation of the odontogenic, periodontal and radiographic signs and other diagnostic elements such as mounted casts and photographs. The final treatment plan is a synthesis of these elements based on the vision and goals the patient has outlined for their oral health and the evidence of prognosis of the treatment options from available research. The myriad of signs, symptoms and options are often complex and decision-making poses challenges.

The benefits of utilizing an interdisciplinary approach wherein the available evidence from within each specialty provides a roadmap to aid in diagnosis and treatment of patient care is highlighted in the two case reports presented below. The format of the presentation follows the C.A.R.E guidelines for case reports.1

Case 1

Introduction

A55-year-old female of Trinidadian origin was referred to the practice with her chief complaint being- she wanted to replace the missing teeth in her mouth. Verbal probing indicated that she was unhappy with the esthetics of her smile because of the ‘spacing’ in between her teeth. (Figs. 1,2) The patient saw her dentist regularly for regular maintenance and had worn a mandibular partial denture infrequently because it was uncomfortable. Her medical history was non-contributory. She experienced environmental allergies. She brushed twice daily and flossed every other day.

Fig. 1

Fig. 2

Examination

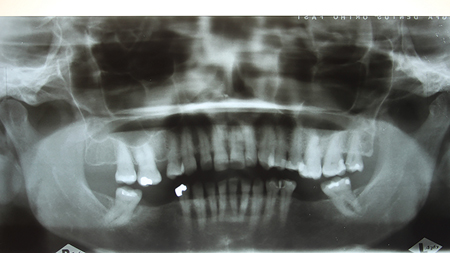

A detailed examination was performed. This included a clinical examination; periapical radiographs, periodontal probing, extra and intra oral photographs and mounted diagnostic models. The primary clinical findings indicated uneven spacing between the lower anterior teeth, missing teeth 36,45,46 (Kennedy Class 3 – Modification 1); supra erupted maxillary posterior teeth contributing to an uneven occlusal plane and a bilateral crossbite. Secondary clinical findings included tooth wear and moderate horizontal bone loss. (Figs. 3-8)

Fig. 3

Fig. 4

Fig. 5

Fig. 6

Fig. 7

Fig. 8

Treatment

The patient consented to a combination treatment that involved both orthodontics and prosthodontics. The orthodontic treatment objectives were outlined as follows: improve the overjet and overbite to establish incisal guidance; achieve closure of all anterior spaces; open room for #15 implant; achieve root parallelism of the adjacent teeth; intrude extruded teeth #16 and # 26 by 2-3mm; correct the crossbite at teeth #13 and #25 and optimize the lower arch spacing to allow for adequate prosthetic replacement of lower missing posterior teeth.

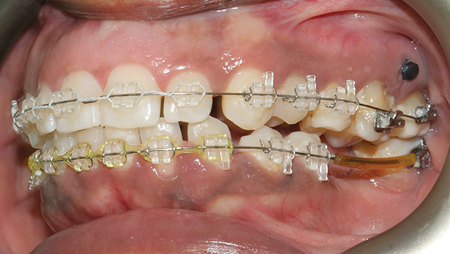

Treatment was performed with orthodontics using fixed appliance therapy and TADs (temporary anchorage devices). (Figs. 9,10) The patient was placed on upper ceramic and lower metal twin appliance (MBT 022 prescription). Aligning and levelling of the arches and space closure was done using sequentially larger wires. Teeth #16 and #26 were intruded by 2-3 mm using buccal and palatal 1.6 mm thick/6 mm long mini screws over a 4-6-month period simultaneously during arch correction. The dental arches were then stabilized and co-ordinated for a 3-month period using heavier stainless-steel wires. Retention was achieved using upper 12-22 and lower 34-44 bonded retainers and removable upper Essix/lower Hawley’s retainer with posterior acrylic blocks. These blocks were added for space maintenance for a period of 6 months until prosthodontic rehabilitation was completed.

Fig. 9

Fig. 10

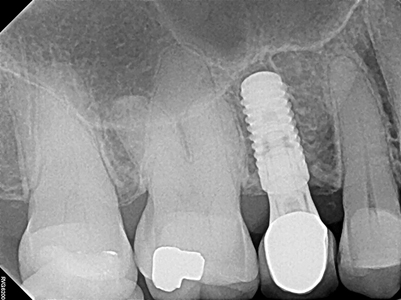

Prosthodontic treatment involved the replacement of tooth # 15 with a dental implant (Straumann BL 4.1 mm RC SLA Active 10mm Ti) and restored with a screw retained dental implant supported crown2 on a Straumann variobase® abutment. The missing teeth in the mandible were replaced with a tooth supported removable partial denture. (Figs. 11-17)

Fig. 11

Fig. 12

Fig. 13

Fig. 14

Fig. 15

Fig. 16

Fig. 17

Case Discussion

Several treatment options were presented to address the patient’s desire to improve her esthetics by replacing the missing teeth in her mouth. Measurements of the available spacing in the maxilla and mandible were calculated to verify the feasibility of replacing the missing teeth with dental implants. Spacing for replacement of 45, 46 and 36 was 14mm- requiring 2 implants each in both these quadrants. The option for replacing the missing teeth in the mandible with 4-unit tooth supported fixed partial dentures was considered. However, this would entail the preparation of vital teeth with possible long-term consequences. In a retrospective chart review, Libby et al identified the list of complications in tooth supported fixed partial dentures ranging from 4 to 16 years. These complications included dental caries (38%), periapical involvement (15%), perforated occlusal surfaces (15%), defective margins (8%), fractured teeth (7%) and porcelain failures (8%).3 In another study, De Backer H et al reported that long span fixed partial dentures demonstrated a survival rate of 68% at 20 years and that caries and loss of retention of the retainers were the main reasons for failure.4 In the maxilla, spacing was inadequate to replace the 15 esthetically with either a removable partial denture, tooth supported fixed bridge or dental implant supported crown. Orthodontic treatment was therefore the most reasonable option to achieve the desired objectives in a predictable way.

Orthodontic treatment lasted 18 months. Tooth 28 was extracted a year into orthodontic treatment as it was causing premature occlusal contact. During orthodontic treatment, the patient was seen for regular follow ups by the prosthodontist to evaluate progress. Particular attention was paid to the root angulation of the adjacent teeth in anticipation of future implant placement. The implant in site 15 was placed fourteen months into orthodontic treatment. The implant access was buccally aligned and therefore the final implant restoration was designed as a one piece “screw-mentable” restoration. A porcelain- fused to metal crown was fabricated to fit over a Straumann variobase® abutment. The abutment and crown were tried in as two separate pieces and cemented extra orally with ‘Multilink Automix’, a universal luting composite (Ivoclar). It was inserted as a one-piece restoration and torqued to 32Ncm. The extra oral cementation was done to eliminate the possibility of subgingival retention of the extruding cement, a common complication if performed as an intra oral procedure.

The initial treatment plan for the lower arch was to replace missing teeth 36,45,46 with implant supported prostheses therefore the excess space in quadrants 3 and 4 was reduced to ensure optimum spacing for prosthetic replacements. However, at the conclusion of orthodontic treatment, the patient elected to replace the missing teeth in the mandible with a tooth supported removable partial denture. The spacing is however ideal for future replacement with implants if the patient elects to pursue this route. Follow up of the treatment has been done up to 2019 (6 year follow up) and the results are well maintained. (Fig. 18) At these follow up appointment the tissue and bone around the implant is evaluated clinical and radiographically and the fit of the partial denture assessed for stability of occlusion and tissue adaptation.

Fig. 18

Case 2

Introduction

A 50-year-old female patient of Asian origin presented to our practice with a complaint that the existing crowns on teeth 11 and 21 were unesthetic. The space between teeth 11 and 21 appeared to be widening over time and she wanted options for ‘closing the gap’.(Fig. 1). Her medical history indicated that she was pre-diabetic. She brushed twice daily and flossed infrequently.

Fig. 1

Examination

A detailed examination of her mouth indicated that teeth 11 and 21 were previously restored with zirconia crowns. Tooth 21 was extruded, demonstrated moderate bone loss with 3+mm of recession; 3mm pocket depth and pathologic migration. The upper midline was off to the left by 6mm. The frenum attachment in the midline was low. Teeth #31/41 and #11/21 demonstrated fremitus indicating signs of traumatic occlusion. Missing teeth 25,26,36 and 46 were not replaced. Teeth 37,47,27 and 21 were drifted and supra-erupted contributing to an uneven occlusal plane and poor esthetics. (Figs. 2-6) Based on Beyrons’s principles of a physiologic occlusion, the occlusion could be termed as ‘non physiologic’.5

Fig. 2

Fig. 3

Fig. 4

Fig. 5

Fig. 6

Secondary clinical findings: Overall the dentition demonstrated generalized moderate bone loss with average pocket depths of 5-6mm. Tooth 44 had 4 mm of attached gingiva. Ridge resorption was classified as moderate. Tooth 47 had an overhanging disto-occlusal restoration. Overjet-5mm; Overbite-30%. Tooth wear was categorized as Grade 1- Generalized occlusal wear and Grade 2- localized wear at the incisal edges of the lower anterior teeth.6

Treatment

After discussing the risks and complications of the treatment options, the patient consented to orthodontic treatment followed by prosthetic restorations. The orthodontic treatment objectives to facilitate prosthodontic rehabilitation were: a correction of the midline by moving the upper midline to the right by 5-6 mm; closure of 11-21 spacing; intrusion of over erupted tooth #21; reduction of trauma from occlusion by eliminating fremitus at 21/31-41 with upper and lower incisor intrusion; correction of lower incisor crowding and rotation; and uprighting the mesially tipped lower posterior teeth to create a favorable occlusal plane to facilitate the future replacement of the missing teeth.

Orthodontic treatment was started prior to the prosthodontic phase with ‘clear aligner therapy’ and the use of TAD’s for midline correction over a 30-month period. A single 6 mm/1.6 mm wide TAD was placed buccally between 15/16, 6 mm above CEJ. Elastics from the TAD to hook at 13 on the aligners were used to gently move the upper midline to the right over an 18-month period. Periodic interproximal reduction was performed on the upper incisors to allow the midline to shift to the right. An initial set of 42 aligners and 2 refinement sets (34 and 16 each) were used to achieve the result. Active orthodontic treatment was completed after 30 months in consultation with the prosthodontist when the treatment objectives were achieved. (Figs. 7,8)

Fig. 7

Fig. 8

The zirconia crowns on teeth 11 and 21 were removed and replaced with Emax crowns (IPS e.max- Ivoclar Vivadent) which were cemented with NX3 NexusTM (third generation universal adhesive resin cement by Kerr). The patient elected not to replace her missing posterior teeth after completion of the anterior crowns. (Figs. 9-14) Therefore, arch stability and retention were achieved using an upper Essix and lower bonded retainer from 33-43 along with a Hawley retainer with posterior bite pads to keep the uprighted teeth in position and the spaces patent impending future replacement.

Fig. 9

Fig. 10

Fig. 11

Fig. 12

Fig. 13

Fig. 14

Case Discussion

The patient’s chief complaint was the unesthetic spacing between teeth 11 and 21 and her desire was to replace the existing crowns on these teeth. Tooth 21 demonstrated a guarded prognosis based on the periodontal diagnosis and the risk of losing this tooth was high. The options for treatment included the replacement of tooth 21 with either a dental implant supported crown, tooth supported fixed bridge, or a tooth supported removable partial denture.

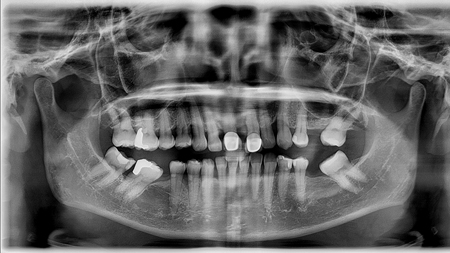

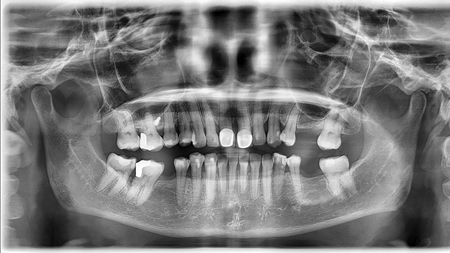

Closure of the space between 11 and 21 and maintenance of the symmetry of these teeth could be reasonably obtained only with orthodontics. Any other option would result in oversize central incisors and the midline would remain compromised. The upper midline was improved significantly by shifting it to the right by 5 mm, correction of the overbite resulted in removal of fremitus by reducing traumatic occlusion, the lower posterior teeth were uprighted and an adequate amount of space was created for a future partial denture in the lower arch. Tooth #21 was intruded resulting in an esthetically improved gingival margin contour compared to pre treatment. (Figs. 2,7) Overall, an improvement in periodontal health was characterized by apparent regeneration of bone when comparing pre and post periapical radiographs of teeth 11 and 21 (Figs. 15,16) and the pre and post panoramic radiographs. (Figs. 17,18)

Fig. 15

Fig. 16

Fig. 17

Fig. 18

The literature is varied on the discussion of the effects of orthodontic treatment on periodontal health. A number of early classic studies demonstrated that in the absence of plaque induced inflammation, orthodontic forces and tooth movement do not cause a breakdown of the periodontal tissues.7,8 In order to obtain good treatment results in patients with reduced periodontal support, the use of light and continuous orthodontic forces, together with the absence of gingival inflammation, are considered to be the most important factors.9 Melsen et al suggested that that the combination of periodontal treatment and orthodontic intrusion may result in new attachment formation and clinical attachment gain if good oral hygiene is maintained.10 In recent times, researchers have sought to determine whether the use of clear aligner therapy might have an added benefit over fixed orthodontic appliances in patients at risk for periodontitis.11,12 Both these studies used meta analysis when comparing similar studies in their reviews. The authors concluded that the level of evidence was considered low due to the heterogeneity of the studies included in the analysis and the inconsistency of the reported results. It is clear however that a high level of patient compliance and effective oral hygiene with good plaque control contributed to an optimal result in this case.

Conclusions

The terms multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary care have often been used interchangeably. The differences between these two approaches were clearly defined by Chop as – “the fundamental difference lies in the collaborative care plan that is only developed in interdisciplinary patient interventions. Multidisciplinary care does not emphasize an integrated approach to care. Multidisciplinary teams are unable to develop a cohesive care plan as each team member uses his or her own expertise to develop individual care goals. In contrast, each team member in an interdisciplinary team build on each team member’s expertise to achieve common, shared goals. Therefore, it is crucial to indicate that multidisciplinary teams work in a team, whereas, interdisciplinary teams engage in teamwork”.13

In dentistry, it is more challenging than in medicine to clearly delineate a treatment approach as being either multidisciplinary or interdisciplinary. A patient’s treatment plan often requires intervention from different specialists during the different treatment phases. While individual providers have their own unique approach to address the specific components of the treatment plan, the prosthodontist or restorative dentist is the person that provides ‘cohesiveness’ to the different components. They identify the restorative needs based on esthetics and function and oversee progress as the treatment phases evolve and ultimately culminate into the final restorative phase. Special emphasis needs to be placed on diagnosis, careful planning, co-ordination and timing of different parts of the therapy for the process to be seamless and to achieve a desirable result. Utilizing a collaborative approach results in a more predictable result, improved outcomes and enhanced satisfaction for both patients and their health care providers.14

Oral Health welcomes this original article.

Acknowledgements: Implant surgery performed by Dr. Vinay Bhide MSc. (Perio); FRCD at Mississauga Dental Specialists.

Laboratory work performed by Randy Kwon at Progenic Dental Lab in Oakville, ON

Informed Consent was obtained from the patients for this publication.

References

- Riley DS, Barber MS, Kienle GS, Aronson JK, von Schoen-Angerer T, Tugwell P, Kiene H, Helfand M, Altman DG, Sox H, Werthmann PG, Moher D, Rison RA, Shamseer L, Koch CA, Sun GH, Hanaway P, Sudak NL, Kaszkin-Bettag M, Carpenter JE, Gagnier JJ. CARE guidelines for case reports: explanation and elaboration document. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017 Sep;89:218-235. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.04.026. Epub 2017 May 18. PMID: 28529185.

- 2017–The Glossary of Prosthodontic Terms.pdf [Internet]. [cited 2020 Sep 21]. Available from: https://www.academyofprosthodontics.org/_Library/ap_articles_download/GPT9.pdf

- Libby G, Arcuri MR, LaVelle WE, Hebl L. Longevity of fixed partial dentures. J Prosthet Dent. 1997 Aug;78(2):127-31. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3913(97)70115-x. PMID: 9260128.

- De Backer H, Van Maele G, De Moor N, Van den Berghe L. Long-term results of short-span versus long-span fixed dental prostheses: an up to 20-year retrospective study. Int J Prosthodont. 2008 Jan-Feb;21(1):75-85. PMID: 18350953.

- Beyron H. Optimal occlusion. Dent Clin North Am. 1969 Jul;13(3):537-54. PMID: 5255314.

- Smith BG, Knight JK. An index for measuring the wear of teeth. Br Dent J. 1984 Jun 23;156(12):435–8.

- Lindhe J, Svanberg G. Influence of trauma from occlusion on progression of experimental periodontitis in the beagle dog. J Clin Periodontol. 1974;1(1):3-14. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1974.tb01234.x. PMID: 4532114.

- Ericsson I, Thilander B, Lindhe J, Okamoto H. The effect of orthodontic tilting movements on the periodontal tissues of infected and non-infected dentitions in dogs. J Clin Periodontol.1977 Nov;4(4):278-93. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1977.tb01900.x. PMID: 271655.

- Corrente G, Abundo R, Re S, Cardaropoli D, Cardaropoli G. Orthodontic movement into infrabony defects in patients with advanced periodontal disease: a clinical and radiological study. J Periodontol. 2003 Aug;74(8):1104-9. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.8.1104. PMID: 14514223.

- Melsen B, Agerbaek N, Eriksen J, Terp S. New attachment through periodontal treatment and orthodontic intrusion. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1988 Aug;94(2):104-16. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(88)90358-7. PMID: 3165238.

- Jiang Q, Li J, Mei L, Du J, Levrini L, Abbate GM, Li H. Periodontal health during orthodontic treatment with clear aligners and fixed appliances: A meta-analysis. J Am Dent Assoc. 2018 Aug;149(8):712-720.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2018.04.010. Epub 2018 Jun 18. PMID: 29921415.

- Flores-Mir C. Clear Aligner Therapy Might Provide a Better Oral Health Environment for Orthodontic Treatment Among Patients at Increased Periodontal Risk. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2019 Jun;19(2):198-199. doi: 10.1016/j.jebdp.2019.05.006. Epub 2019 May 6. PMID: 31326056.

- Robnett and Chop – 2015 – Gerontology for the Health Care Professional.pdf [Internet]. [cited 2020 Apr 18]. Available from: http://samples.jbpub.m/9781284038873/ 9781284030525_FMxx.pdf

- Mitchell GK, Tieman JJ, Shelby-James TM. Multidisciplinary care planning and teamwork in primary care. Med J Aust. 2008 21;188(S8): S61-64.

About the Author

Dr. Neena D’Souza is an Adjunct Professor and teaches in the Graduate Prosthodontic Program at the Faculty of Dentistry, University of Toronto. She practices at Mississauga Dental Specialists, an interdisciplinary specialty practice in Mississauga, Ontario. Correspondence may be directed to Dr. D’Souza at drndsouza@dentalspecialist.ca

Dr. Neena D’Souza is an Adjunct Professor and teaches in the Graduate Prosthodontic Program at the Faculty of Dentistry, University of Toronto. She practices at Mississauga Dental Specialists, an interdisciplinary specialty practice in Mississauga, Ontario. Correspondence may be directed to Dr. D’Souza at drndsouza@dentalspecialist.ca

Dr. Girish Deshpande is a practising orthodontist at GD Orthodontics, within Mississauga Dental Specialists and teaches at the Faculty of Dentistry, University of Toronto.

Dr. Girish Deshpande is a practising orthodontist at GD Orthodontics, within Mississauga Dental Specialists and teaches at the Faculty of Dentistry, University of Toronto.

RELATED ARTICLE: Interdisciplinary Therapy In Aesthetic Dentistry