Convenient Engineering’, a term coined by Michael Cohen ‘Interdisciplinary Treatment Planning, Quint Dec. 2011’, states that “while planning cases on ‘auto-pilot’ may save time and money and may be compatible with both the wishes of the dentist and the patient, it may also be thought of as ‘CONVENIENT ENGINEERING’ and is not necessarily in the best interest of all concerned. This way of thinking also preempts the opportunity to ‘fit the pieces of the puzzle’ together so that they actually ‘fit better’ and erodes the creativity and the innovation within us. The result is often MONOTONY and the LOSS of PASSION for what we do”.

This is certainly true for implant dentistry. The surgical phase for any dental-implant-reconstruction starts with a prosthetically driven treatment plan and it’s imperative that this treatment plan provides a clear vision of the ‘end point’, prior to initiating any irreversible treatment. The implant dentist must resist the temptation of treatment planning on ‘auto-pilot’ but rather develop a solution that is well conceived, well organized, and achievable and in the best interest of the patient and not simply the most convenient.

This article describes the treatment planning steps involved in creating a dental implant solution for a case of a failing dentition, making use of hopeless teeth and tooth roots) to serve as temporary abutments for a fixed-provisional prosthesis, while maintaining as much of the natural dentition as possible. The goal was to provide chewing efficiency and patient comfort during the osseointegration healing period while simultaneously preventing premature loading of newly placed dental implants as the patient is transitioned to the final definitive prostheses.

A discussion on implant loading protocols is beyond the scope of this article, however, it must be noted in a quote by Darin Dichter, that “in the early years of osseointegrated implant dentistry, most experts advocated delaying prosthetic loading for three to six months. It was believed that this time frame was sufficient to allow for “stress-free” healing and could compensate for patient-specific factors as well as not-yet optimized surgical protocols, prosthetic protocols and implant designs. Although derived empirically, this protocol set the stage for the wide success and acceptance of dental implants as a viable treatment option”.1

Is this true today? Some authors argue that delayed loading increases the success rate of osseointegration,2 that early loading imposes a significantly higher risk of implant failure than does conventional loading and that although early implant loading is convenient and comfortable for patients, this method still cannot achieve the same clinical outcomes as the conventional loading method.3 Some go on to say that although no significant differences between early and immediate loading protocols in single implant crowns with regard to survival rate or marginal bone loss has been well documented, immediate loading of fixed partial-denture prostheses is not widely accepted.4,5 Others, however, argue the overall implant survival rate of immediately loaded implants is similar to long-term results achieved with the conventional 2-stage implant protocol.6,7 Thus using the scientific literature to justify a specific loading protocol for newly placed dental

implants can be a difficult challenge.

The last decade has also seen a growing trend of convenient solutions requiring the removal of otherwise healthy teeth to accommodate a ‘convenient implant restoration’.7 There is now mounting evidence that long-standing and otherwise previously healthy dental implants have an increasing risk of developing peri-implantitis in the future.8-14 This revelation coupled with little evidence to support any recommendation for specific therapy for peri-implantitis,15 is spurring new dialogue on the need to revisit the classification for the prognosis of an individual tooth/teeth (references). A full discussion on tooth prognosis is beyond the scope of this article but the reader is referred to (see references). Dental implants when indicated, should therefore be used judiciously to ‘help save the remaining teeth, and not to replace them.

In this article we will highlight the reverse strategy of using ‘hopeless teeth and/or tooth roots to help safeguard newly placed dental implants’ from premature loading during the osseointegration period by serving as temporary abutments for fixed-partial temporary prostheses. These provisional prostheses can accept occlusal load while facilitating a smooth transition to final prosthesis. As such, the ‘rush to finish’ becomes less of a factor.

The following case will serve to illustrate the benefit of such planning. All surgery was completed with conventional CT scans and Simplant software to help in the planning stages. All implants were placed free hand to reduce costs. Surgical guides would add costs and time to the planning stages but should reduce surgical time. They may or may not improve results. There use is highly recommended for less experienced implant dentists.

Patient: 75 year-old male.

MH: Medical history was non-contributory.

DH: Patient underwent orthodontic treatment as an elder to help manage skeletal disharmony between retrognathic maxilla and prognathic mandible. Orthodontic retention was fraught with ongoing caries issues concurrent with multiple food traps and compromised oral hygiene.

CC: On/off pain, thermal sensitivity, difficulty chewing and generalized food traps.

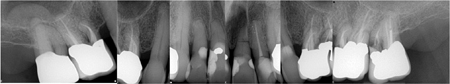

EX: Endodontic pathology and compromised periodontium #16, recurrent caries, root fracture #26 and 27, and generalized, chronic stage II Cat B periodontal bone loss.

Treatment Plan:

The final treatment plan would require implants in the #16, 14, 12, 22, 24 and 26 positions. The fixed provisional prosthesis would make use of provisional abutments on #17 and 27, 13, 23 and 11. The plan would involve serial extractions and grafting procedures to preserve bone volume in the ideal sites while avoiding any load on the newly grafted sites using strategic teeth to serve as provisional abutments. Patient accepted this solution and agreed to keep teeth #13 and #23. Benefits include cuspid rise occlusion, bone preservation and proprioception (also to minimize the significant risk with adjacent implants in the anterior zone).

Appointment 1.

This was necessary to manage traumatic horizontal root fracture #21.

Appointment 2:

- N.B. Existing #17 to be converted to #16, existing #16 to be converted to #15 and 14, existing #26 to be converted to #24 and 25. Lastly #27 will be converted to 26.

- Prepare #17, 27 13, 11 and 23 and provisionalization.

- Extraction of #16, 12, 22 and 26. (Socket grafting #16, and 26 to preserve existing bone volume).

- Immediate implant placement in sites #12, 22, 14 and 24.

- Reassess healing clinically and radiographically over a 4-6 month healing period.

September 20, 2016

This case was chosen to demonstrate how a fixed transitional prosthesis using hopeless teeth and tooth roots can provide a smooth transition to the definitive prostheses. This is a divergence from the ‘Convenient Engineering’ approach often used in implant dentistry, but was conceived with the patient’s best interest in mind. The patient were given alternative options including hybrid-type immediate prostheses, bar over-dentures and conventional maxillary and mandibular complete dentures but chose this alternative because of stable provisionals with ‘a no rush to finish’ approach and because of the progressive transitioning from the natural dentition to the definitive implant prostheses.

November 10, 2016

Bis-bake for try-in

Immediate insert

The before compared to the one-month post-op

Before

Abutment try-in

One-month post-op

Oral Health welcomes this original article.

References

- Prof. Markus B. Hürzeler, University of Zurich, Swiss of Periodontology.

- Massimo Simion International Periodontal and Restorative Conference, Boston June, 2018.

- 19 published studies that looked at either implant survival rates or tooth survival rates over at least 15 years. Dr. Liran Levin, Dept. of Perio, Israel Institute of Technology/Harvard School of Dental Medicine in Boston. Journal American Dental Association, October.

- Prosthetic Loading: Darin Dichter on August 13, 2018 (Spear education).

- Clinical efficacy of early loading versus conventional loading of dental implants. Yanfei Zhu, Xinyi Zheng, Guanqi Zeng, Yi Xu, Xinhua Qu, Min Zhu, and Eryi Lu, Sci Rep. 2015; 5: 15995.

- Clin Oral Implants Res. 2010 May;21(5):481-9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2009.01898.x. Immediate vs. early loading of dental implants: 3-year results of a randomized controlled clinical trial. Zembic A, Glauser R, Khraisat A, Hämmerle CH.

- J Prosth Dent. 2018 Jul;120(1):25-34. doi: 10.1016/J. Prosth Dent.2017.12.006/Epub 2018 Apr 25. Immediate versus early loading of single dental implants: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pigozzo MN, Rebelo da Costa T, Sesma N, Laganá DC.

- Immediate loading implants: review of the critical aspects. Oral and Implantology (Rome), 2017 Apr-Jun; 10(2): 129–139. Published online Sep 27, 2017: 10.11138/orl/2017.10.2.129, PMCID: PMC5965071, PMID: 29876038. L.Tettamanti et al.

- Survival Rate of Immediately vs Delayed Loaded Implants: Analysis of the Current Literature Georgios Romanos, DDS, PhD Stuart Froum, DDS, MS Cyril Hery, DDS, Sang-Choon Cho, DDS Dennis Tarnow, DDS. Journal of Oral Implantology 315-324;Vol.36:(4)/2010.

- Survival and complications: A 9- to 15-year retrospective follow-up of dental implant therapy. Adler L , et al. J Oral Rehab 2019 Jul 29.

- Surgical management of Peri-implantitis Heitz-Mayfield L, et al. Int J Oral Maxillofac Impl 2014;29(Suppl);325-345.

- Peri-implantitis: A Comprehensive Overview Of Systematic Reviews. Ting M et al. J Oral Impl 2018;44(3);225-247.

- Peri-implantitis prevalence, incidence rate, and risk factors: A study of electronic health records at a U.S. dental school. Clinical Oral Impl Res 2019 Apr 30(4):306-314. Kordbacheh Changi K et al Columbia New York, Div. of Perio.

- Prevalence, Etiology and Treatment of Peri-Implant Mucositis and Peri-Implantitis: A Survey of Periodontists in the United States. J. Perio 2016 May;87(5):493-501. Finkelman M et al. Department of Periodontology, School of Dental Medicine, Tufts University, Boston, MA.

- Prevalence of peri-implantitis and peri-implant mucositis: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dent 2017 July;62:1-12. Lee CT et al. Dept. Perio, University of Texas Health Sciences.

- Increasing Prevalence of Peri-implantitis: How Will We Manage? D.P. Tarnow. Journal of Dental Research 2016, Vol. 95(1) 7–8 © International & American Associations for Dental Research 2015.

About the Author

Domenic Belcastro, received his Masters degree from Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Implant Surgery at Lille University Medical School, France, 2006–2010. Scientific director of Advanced Occlusion and Esthetics CE program in Toronto. Clinical Instructor University of Toronto Department of Restorative Dentistry 2012–2014.An alumnus of the Pankey Institute (Key Biscayne Fla.). Served on the committee of the RCDSO PLP program. Maintains a private practice in Toronto.

Domenic Belcastro, received his Masters degree from Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Implant Surgery at Lille University Medical School, France, 2006–2010. Scientific director of Advanced Occlusion and Esthetics CE program in Toronto. Clinical Instructor University of Toronto Department of Restorative Dentistry 2012–2014.An alumnus of the Pankey Institute (Key Biscayne Fla.). Served on the committee of the RCDSO PLP program. Maintains a private practice in Toronto.