Dentists are commonly confronted with the diagnostic and treatment challenges associated with a person who has TM joint pain, TM joint clicking and limited opening resulting from certain TM joint conditions. Paramount in our approach is the paradigm to “do no harm1” and to achieve this goal, the clinician must understand the nature of these conditions, their diagnosis and their basic management.

Normal TMJ Anatomy2

As indicated by its name, the temporomandibular joint is the articulation between the mandibular condyle and the temporal bone fossa. These bones are buffered by a biconcave disc of fibrocartilage that is best thought of by its boundary attachments:

- The lateral disc is anchored to the mandibular condyle via collateral ligaments, but is also integrated into the joint capsule itself. These ligaments serve to stabilize the disc in the joint.

- The posterior disc is connected to the highly vascularized and innervated retrodiscal tissues, which connect to both the condyle and the temporalis bone. The retrodiscal tissues are also connected to the discomalleolar ligament,3 which originates in the middle ear. The retrodiscal tissue is passive in the closed position, but will limit the motion of the disc during maximum opening.

- The anterior disc has connection with the joint capsule and the superior head of the lateral pterygoid muscle. The superior portion of the lateral pterygoid appears to contract during closing, stabilizing the disc during chewing.

The joint is innervated by the auriculotemporal and masseteric nerves, which are branches of V34.

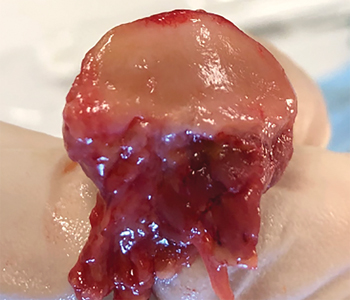

Fig. 1

Normal TMJ Function

It is commonly accepted that the temporomandibular joint has both rotational movement and translational movement, making it a ginglymoarthroidial joint. The mandibular condyle will rotate on the inferior surface of the disc and the superior surface of the disc will slide from the fossa up the articular eminence. Right and left lateral movements primarily involve translational movements by the contralateral joint (e.g. a left lateral movement involves translation of the right condyle). The complex nature of all mandibular movements is beyond the scope of this paper, but these basic movements can be demonstrated in any clinical setting.

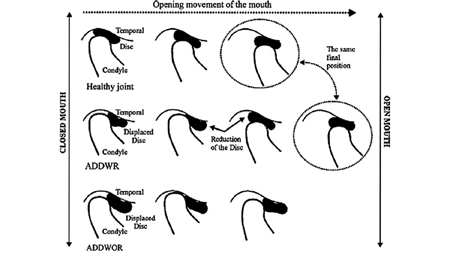

Fig. 2

Fig. 3

Disc Displacement with Reduction (DDWR)

This is a relatively common phenomenon that occurs in as much as 33%7 of the population aged 18-55 and is characterized by an audible click, pop or crack on opening and/or closing. Typically, the joint sound will be more pronounced on opening and usually produces no pain. The disc displacement is often caused by elongation of the lateral collateral ligaments and/or the retrodiscal tissues, resulting in the disc displacing anteromedially to the condyle. This elongation or “stretching” of the ligaments is the result of microtrauma or macrotrauma.

- Microtrauma:8 daily, repetitive strain on the joint from parafunctional habits such as severe bruxism, clenching, gum chewing, cheek biting, lip biting or pen biting. This is the more common cause of a disc displacement and these patients will often show significant tooth wear, signs of cheek or lip biting, have well-developed masseter and temporalis muscles and will often continually clench their teeth during your initial assessment.

- Macrotrauma:9 a single event, such as a blow to the jaw, a surgical procedure that required intubation, or a dental procedure that required prolonged, excessive opening such as a 3rd molar extraction. Patients will also describe the “trauma” as biting into something or yawning. While less commonly the cause of a disc displacement, these events will often result in someone showing up to your office due to moderate or severe jaw pain.

Whether a repetitive strain issue from a gummy bear habit or a single event, such as a baseball bat or airbag to the face, a displaced disc will typically remain that way during rest. Many efforts to “recapture” the disc will often end in frustration and a loss of confidence by your patient. When ligaments elongate, they remain in that state, so management approaches must appreciate this fact.

When two anatomical structures become misaligned, their re-alignment is called a “reduction.”10 While this may seem like a bit of a clunky term, it is firmly entrenched in the medical lexicon, so it’s best to accept it. If you fracture your leg and the bones are displaced, a surgeon will reduce the fracture by bringing the fractured segments back into normal position; if you dislocate your finger, you or someone you trust will “snap” it back into place or reduce the dislocation (of course, this is best demonstrated by a movie hero who reduces his dislocated shoulder by slamming it into a wall…) and when your TMJ articular disc has displaced, condyle translation will push against the thickened posterior aspect of the disc until the disc reduces, creating the pop, click or crack that is characteristic of this condition.

Over time, the disc may become abraded by the condyle, especially if the condyle has a more flattened architecture. Ongoing abrasion of the disc may lead to its perforation, resulting in continued popping with a grinding sound or “crepitus” and worsening of the condition.

DDWR with Episodic Locking

Some people will report a history of jaw joint clicking that has recently begun to lock, where they can only partially open until they are able to manipulate their jaw so that it will release. There are varying degrees of this condition and people will report a lock that occurs only a few times a month, to as much as several times per day. This condition may or may not be accompanied by pain, but is almost always stressful for the sufferer.

This is a sign of the worsening of the joint condition and often leads to a more debilitating condition – a disc displacement that no longer reduces.

Disc Displacement without/no Reduction (DDWoR or DDNR)

Also referred to as a closed lock, this is a less-common condition than DDWR and is often a consequence of continued microtrauma to a joint with a reducing disc displacement, but may also be the result of a single traumatic event.

This person will usually present to your clinic with a triad of symptoms:11 a history of joint clicking, but the click has either mostly or completely disappeared; they have a limited mandibular range of motion (normal opening is >40 mm); they will report significant pain in the affected joint. It is important to understand why these three symptoms show up in almost every patient who reports a recent DDNR, not necessarily because you want to manage this condition, but because as the person’s clinician, you need to explain it to them in order to ease their stress.

Why no click? If the disc no longer reduces, it will no longer click. However, it is important to remember that these conditions are on something of a continuum – a person may report that their joint would always click when they opened wide, but after yawning or eating too many gummy bears, the clicking has stopped almost entirely.

Why limited opening? As the condyle begins its translational movement, its movement is impeded by the disc, resulting in limited opening. Think of a pair of socks stuck behind a drawer – as you try to close the drawer, its movement is impeded by the socks, so you can’t completely close it.

Why the pain? This condition is a painful because the ligaments and/or the retrodiscal tissues will have been further elongated or otherwise damaged. DDNR often presents as an acute condition because of pain. Not many people care about clicking loss; they may moderately care about decreased opening; but pain derails everyone’s day. Pain is defined as unpleasant and most of us will do just about anything to rid ourselves of this demon.

Fig. 4

Diagnosing DDWR, DDWR with episodic locking & DDWoR/DDNR4,11

To accurately diagnose any pain condition, a clinician must first gather a subjective report of their patient’s condition. This includes the following:

- Chief complaints: a laundry list of what brought them into your office, usually written in their own words.

- History of chief complaints: a brief summary of what happened at the time the condition arose (e.g. trauma, dental work, surgery, etc.), what they have done about it, etc.

- Specifics about their pain, including: onset, location, pain quality (e.g. sharp, dull, etc.), frequency (every day, only while eating or opening wide), duration (a few seconds? All day?), VAS 0-10 (it ain’t gospel, but it simply offers you a glimpse into how their pain is affecting them), and what makes their condition better or worse.

After gathering a history, you can perform a physical exam. This can be abbreviated as you are usually seeing this person on an emergency basis during your lunch break. Palpate with light pressure (1-2 kg/cm2) for 1-2 seconds and ask them to rate their pain as 1, 2 or 3. 1 is mild, or 1-3/10; 2 is moderate or 4-6/10; 3 is severe or 7-10/10. Severe is usually easy to identify as the person will withdraw or move your hand away. Palpate one area at a time: right masseter, right temporalis, right condyle. Then move to the other side. After palpation, have them open and close with your fingers on both condyles. You are feeling for any popping or clicking. A true disc displacement can usually be felt with your fingers and should be coincident with the pop or click. If possible, listen to the joint with a stethoscope.

As with any procedure, you must practice this examination technique to become proficient. Make it a habit to ask these questions of anyone who has pain, not just musculoskeletal pain. Palpate the muscles and joints of new patients or during recall visits. If someone has an asymptomatic clicking joint, palpate it as they open and close so that you can develop a feel for this condition and its varied presentations.

After palpation and auscultation of the temporomandibular joints, measure their mandibular range of motion. Measure the following:

- Overbite: mm

- Overjet: mm

- Midline: centred or mm right/left

- Protrusion (use a perio probe): overjet + mm lower anterior teeth protrude past upper anterior teeth (e.g. if the lower teeth move 6 mm beyond the upper teeth and the overjet is 3 mm, the total mandibular protrusion is 9 mm).

- Right lateral movement: measured in mm, + or – the midline (e.g. if midline is 1 mm to the right and their right movement is 10 mm, subtract 1 mm because the lower jaw had a “head start”).

- Pain free opening: how far can they open without pain. This is interincisal distance + overbite (e.g. their overbite is 3 mm and they open 22 mm without pain, making their pain free opening 25 mm).

- Maximum active opening: how far can they open, regardless of pain (e.g. 42 mm interincisal distance + 3 mm overbite = 45 mm).

- Assisted opening: How far you can passively stretch them open beyond their maximum active opening. Be cautious doing this with anyone who can open past 45-50 mm. This is well within normal opening and typically needn’t be tested.

Lastly, make note of any jaw deviation or deflection. Deviation is lateral movement that will return to midline at maximum opening. For example, if someone has a midline that is 2 mm to the left, their jaw may move right, then left, then return to 2 mm to the left at maximum opening. Deflection is movement away from the midline (toward the affected joint) at maximum opening.

Diagnosing DDWR

This person will have a joint that clicks at least 2 out of 3 times when opening. There may be a closing click, referred to as a reciprocal click. This click is asymptomatic in most who have this condition. Their opening will be normal (>40 mm) and they often have deviation, but no deflection.

Diagnosing DDWR with episodic locking

Same as above, but the person will report locking. You will often not see this during your examination, but you will note they are hesitant to open wide as this may induce a lock. Do not have them open wide if you are not prepared to help them reduce the lock.

Diagnosing DDWoR/DDNR

This person will present typically present with: clicking absence; pain; and limited opening.

History will usually reveal trauma or some moment when they experienced pain in their joint (while eating, during a dental appointment, upon rising in the morning, etc.), followed immediately by limited opening. They may or may not notice the loss of their joint click. They will also report that NSAID’s and ice will make it feel better, while hard/chewy food and opening wide (e.g. yawning) make it worse. The pain will be sharp or dull and they will often point right at their affected joint.

The joint will typically be moderately/severely painful to palpation and often the associated masseter/temporalis will have mild discomfort. Pain free opening will usually be limited and maximum active opening will be <38 mm. You will see pain with mandibular movements and the jaw will deflect to the affected side (i.e. a left TMJ DDNR will have a jaw deflect to the left on maximum opening). When you measure assisted opening, you will notice a “hard end-feel” of the mandible. It will not move – don’t try to make it move!

Management of DDWR7

If asymptomatic, management is preventive. We advise:

- • Education on the condition

- • Reduce number of clicks during each day

- • Avoid opening wide

- • Cut food into smaller pieces

- • Avoid hard/chewy food

- • Avoid prolonged dental treatment and take any necessary breaks

- • Perform a hinge exercise daily by placing the tongue on the roof of the mouth as though you are saying the letter “N” and open/close 5-6 times to keep the joint lubricated (make sure there is no joint clicking)

- • If there is evidence of bruxism, consider a stabilization appliance

- • Ask your patient to contact the office immediately if this condition becomes symptomatic

If symptomatic, all of the protocols outlined above are used. Also consider:

- NSAID for pain management. Consider alternating every 3 hours with acetaminophen*

- Short term steroid, if appropriate**

- Ice the affected joint 3 times daily for 10-20 minutes

- If pain does not resolve, consider a steroid/local anesthetic joint injection or hyaluronic acid injection

- If in the acute phase (i.e. the clicking started within the past 4-6 weeks) consider an anterior repositioning appliance to be worn nightly for 4 weeks, then transitioned to a stabilization appliance. Some authors suggest wearing this appliance for up to 20 hours per day13, but a repositioning appliance may be fraught with complications and should only be used if you have been appropriately trained

- Reassure your patient that this condition will improve in time.

*only use when medically appropriate.

**only use when medically appropriate and if you have experience with these medications.

Management of DDWR with episodic locking

- All of the above protocols

Management of DDWoR/DDNR14

- Education on the condition

- Avoid hard/chewy food

- Cut food into smaller pieces

- Ice 3 times daily for 10-20 minutes

- NSAID for pain management. Consider a longer-acting medication like naproxen 220-500 mg bid*

- Consider steroid or opioid medication for short-term use**

- Joint injection with steroid and local anesthetic

- Increase mandibular range of motion with passive stretching exercise (see image)

- Stabilization appliance should be considered when range of motion has been increased

- Reassure your patient – this is a very stressful condition

* only use when medically appropriate.

** only use when medically appropriate and if you have experience with these medications.

Conclusion

These are conditions that are common in most dental practices and their identification is usually straight forward if the above diagnostic protocol is practised and used. Shortcuts in diagnostic protocols will usually result lead to inaccurate or partially accurate diagnosis, resulting in heartache for both the clinician and patient alike. As with most chronic conditions, management of these conditions can be difficult but rewarding. Proceeding in a methodical, stepwise fashion in diagnosis, management and follow up care is critical to success. As always, rely on your community of colleagues – as Dr. Jack Broussard says: “Share the risk, share the wealth.”

Oral Health welcomes this original article.

References

- BMJ 2019;366:l4734.

- Bordoni B, Varacallo M. Anatomy, Head and Neck, Temporomandibular Joint. [Updated 2019 Feb 6]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538486/

- Rodríguez-Vázquez JF, Mérida-Velasco JR, Mérida-Velasco JA, Jiménez-Collado J. Anatomical considerations on the discomalleolar ligament. J Anat. 1998;192 ( Pt 4)(Pt 4):617-621. doi:10.1046/j.1469-7580.1998.19240617.x.

- Maini K, Dua A. Temporomandibular Joint Syndrome. [Updated 2019 Dec 14]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK551612/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538486/figure/article-36258.image.f1/?report=objectonly.

- Image from cadaver dissection by Dr. Thomas Shackleton & Dr. Ivonne Hernandez May 2019.

- POLUHA, Rodrigo Lorenzi et al. Temporomandibular joint disc displacement with reduction: a review of mechanisms and clinical presentation. J. Appl. Oral Sci. [online]. 2019, vol.27 [cited 2020-07-06], e20180433. Available from: <http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1678-77572019000100701&lng=en&nrm=iso>. Epub Feb 21, 2019. ISSN 1678-7765. https://doi.org/10.1590/1678-7757-2018-0433.

- Bell’s Oral and Facial Pain–Seventh edition, pp 939. Okeson, Jeffrey P. 2014 Quintessence Publishing Co, Inc 4350 Chandler Drive, Hanover Park, IL 60133.

- Bell’s Oral and Facial Pain–Seventh edition, pp 936. Okeson, Jeffrey P. 2014 Quintessence Publishing Co, Inc 4350 Chandler Drive, Hanover Park, IL 60133.

- https://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/Reductions

- J Can Dent Assoc 2014;80:e60.

- Pérez del Palomar A, Doblaré M. An accurate simulation model of anteriorly displaced TMJ discs with and without reduction. Med Eng Phys. 2007;29(2):216-226. doi:10.1016/j.medengphy.2006.02.009.

- Pihut M, Gorecka M, Ceranowicz P, Wieckiewicz M. The Efficiency of Anterior Repositioning Splints in the Management of Pain Related to Temporomandibular Joint Disc Displacement with Reduction. Pain Res Manag. 2018;2018:9089286. Published 2018 Feb 21. doi:10.1155/2018/9089286.

- Al-Baghdadi M, Durham J, Araujo-Soares V, Robalino S, Errington L, Steele J. TMJ Disc Displacement without Reduction Management: A Systematic Review. J Dent Res. 2014;93(7 Suppl):37S-51S. doi:10.1177/0022034514528333.

About the Author

Dr. Shackleton graduated from Northwestern University Dental School in Chicago and completed a master’s degree in Oral Medicine/Orofacial Pain from the University of Southern California. He is a Diplomate of the American Board of Orofacial Pain and a Fellow of the American Academy of Orofacial Pain. He has taught endodontics and orofacial pain at the University of Alberta and the University of New England, is a regular contributor to CDA Oasis and has published in multiple peer-reviewed dental journals. He has a private practice in Calgary, AB and can be reached at tom@tsoralhealth.com

Dr. Shackleton graduated from Northwestern University Dental School in Chicago and completed a master’s degree in Oral Medicine/Orofacial Pain from the University of Southern California. He is a Diplomate of the American Board of Orofacial Pain and a Fellow of the American Academy of Orofacial Pain. He has taught endodontics and orofacial pain at the University of Alberta and the University of New England, is a regular contributor to CDA Oasis and has published in multiple peer-reviewed dental journals. He has a private practice in Calgary, AB and can be reached at tom@tsoralhealth.com