Introduction

The maxillary lateral incisors are the most common congenitally missing teeth after the upper and lower second premolars. Gender differences are negligible, with women slightly more affected than men.1 Agenesis of the maxillary lateral incisors presents a significant challenge to clinicians since it negatively impacts dental and facial esthetics. Furthermore, this condition impacts function in young patients. Space opening/maintenance followed by implant placement has emerged as an important treatment approach.2,3 An interdisciplinary approach is necessary to provide the most predictable treatment results when implants are inserted to replace congenitally missing teeth.4

Case Report:

A 21-year-old female presented to the orthodontist in 2015 with the chief complaint of a median diastema. She was skeletal Class I but had several congenitally missing teeth, including upper lateral incisors, maximally bicuspids, and the lower right second molar. The residual spaces in the upper arch were asymmetric and the orthodontic treatment plan was to distribute spaces symmetrically in the right and left quadrants in order to create the appropriate spaces for the necessary implants. The maxillary left canine was moved distally, creating enough space for two implants on the upper left side.

The upper right quadrant responded to orthodontic treatment less successfully than did the left. The resulting space was more than the mesiodistal width of the lateral tooth but less than the space required for two teeth.

Following the less-than-ideal outcome of the orthodontic phase, likely exacerbated by the lack of pretreatment prosthodontic and esthetic planning, endosseous implant surgery was commenced prior to the prosthetic consultation. After implant placement, the orthodontist referred the patient to the prosthodontic practice for a consultation to determine how an esthetic outcome could be achieved.

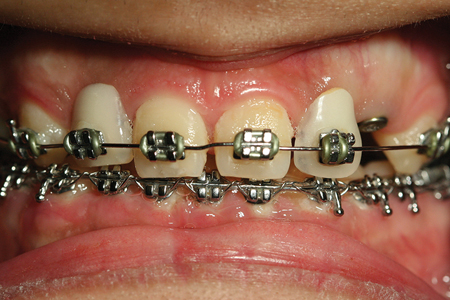

The patient was first examined by the restorative team when she was 22 years old, after orthodontics and implant placement. The patient was wearing brackets at the first prosthetic consultation appointment with a 1.5 mm diastema between the central incisors. There were three 3.3 mm × 12 mm Bone Level Tapered Implants (Straumann AG, Waldenburg, Switzerland). Artificial teeth were attached to the orthodontic wire as temporary restorations, attempting to overcome the aesthetic problem of missing teeth. (Figs. 1 & 2)

Fig. 1

Fig. 2

Although a thorough anatomical evaluation of hard and soft tissues should be considered at the earliest stages of treatment planning to recommend appropriate intervention and to predict treatment results, these essential steps had not been done for this patient.5 Intraoral examination revealed the presence of a right maxillary primary first molar of which the patient had been unaware.

In addition to space management problems, the gingival level of the implant at 12, when compared to the implants on the left anterior segment, was another significant esthetic challenge for prosthodontic restoration.

Evaluating the potential complications of any further orthodontic movement, the orthodontist confirmed that closing the diastema was the only possible minor correction at this point. Following the orthodontic movement of the central incisors to close the diastema, prosthetic procedures were commenced. (Fig. 3)

Fig. 3

The predicted aesthetic prognosis for this patient was very guarded in light of the limitations imposed by previous orthodontic treatment and implant placement.

Prosthetic phase

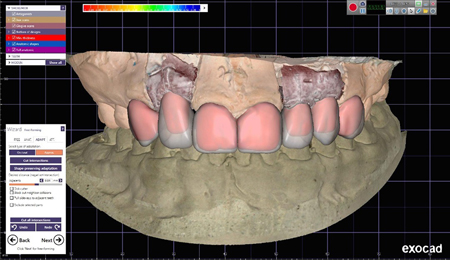

Addition polyvinyl silicone impression material (Elite HD, Zhermack SpA, Badia Polesine, Italy) was used to take a closed tray impression. After mounting the upper and lower models on the articulator and using the Imetric (Imetric 4D Imaging, Courgenay, Switzerland) Lab Scanner, a virtual wax up was created using the Exocad (Exocad GmbH, Darmstadt, Germany) Smile Design Module, (Fig. 4) and printed with the Asiga (Asiga America, Ann Arbor MI) MAX 3D printer to serve as an index for the esthetic mockup. (Fig. 5)

Fig. 4

Fig. 5

According to the 3D printed model, and on the primary stone model, three PEEK abutments were prepared to receive CAD/CAM PMMA provisional crowns. Upon inserting the abutments intraorally, and trying-in the PMMA units, in addition to distinguishable discrepancy at the gingival levels of implants on two sides of the arch, it became evident that porcelain laminate veneers would be required for teeth 13, 11, 21, and 23 to properly manage the esthetics of the anterior segment. Limited restorative space on the maxillary left side is visible in Fig. 1. Despite the retained deciduous maxillary right molar’s impact on the side view of her smile, the patient declined restorative procedure for this tooth for budgetary reasons.

Upon patient acceptance of the new functional and esthetic treatment plan, minimally invasive Biomimetic tooth preparations were performed, followed by a single-stage polyvinyl siloxane closed tray impression to register the prepared natural teeth and implants simultaneously.

New PEEK abutments were trimmed and adjusted to form appropriate cross sectional and emergence profiles for fabricating a one-piece provisional restoration for the laminate-prepared natural teeth and implant restorations. After spot etching 13, 11, 21, and 23, a single-unit provisional for the anterior segment was fabricated directly using Luxatemp bisacryl, shade B1, (DMG America, Ridgefield Park, NJ) and a silicone index from the printed model. (Figs. 6 & 7)

Fig. 6

Fig. 7

After careful evaluation of the occlusal relationships on the articulator, due to limited interocclusal space for 22 and 23, and to have a shade continuity on all restorations, veneers and crowns (IPSe.max CAD, Ivoclar/Vivadent, Schaan, Liechtenstein) were planned for all natural teeth and implants.

Due to limited restorative space for the implant crown, monolithic lithium disilicate was pressed using abutments (RCVariobase, =3.3mm, H=5mm to serve as the infrastructure. Finally, pressed laminate veneers (shade BL1) were fabricated for all the natural teeth and the hybrid abutments. (Figs. 8 & 9)

Fig. 8

Fig. 9

Although the Vita Classic shade A2 matched and blended with the existing lower incisors more closely, the patient insisted on shade BL1 for her upper anterior restorations. The influences driving such desires are many and varied, but may be partly related to news media that bombard the young with images of perceived “beauty” such as dazzling white teeth.6

After removing the provisional restoration, the bonding surfaces of the prepared teeth were cleaned under proper isolation, and all the restorations were positioned using a try-in paste. (Fig. 10)

Fig. 10

Prior to bonding the laminate veneers, the titanium abutments were sandblasted and alloy primer was applied on their surfaces.7 The intaglio surfaces of hybrid abutments were cleaned with Ivoclean (Ivoclar Vivadent, Schaan, Lichtenshtein) to enhance adhesion between the indirect restorative materials and the adhesive cements (by effectively eliminating contaminated bonding material).8 Each abutment was acid-etched with 4% hydrofluoric acid for 20 seconds, cleaned again with 37% phosphoric acid, and then placed in an ultrasonic cleaner for 5 minutes to remove any remaining salts. After silane application and hot air activation, each abutment was left untouched for 5 minutes to ensure maximum silane activation. Multilink hybrid abutment cement (Ivoclar Vivadent AG, Schaan, Liechtenstein) was used to bond the Straumann Variobase (Straumann AG, Waldenburg, Switzerland) to the lithium disilicate hybrid abutments.

The bonding surfaces of 13, 11, 21, and 23 were acid-etched, rinsed, and dried. The bonding agent was thinned with gentle, dry airflow. The luting composite was applied to the intaglio surface of the laminate veneers, and they were gently seated. Following the careful cleaning of excess cement, the veneers were tack-cured and dental floss was used to remove the interdental excess cement. All the margins were covered with glycerin gel and final curing was carried on each surface. Meticulous removal of any remaining excess cement with steel curettes under magnification is mandatory.

The post-treatment result indicates a significantly improved smile with better facial esthetics. (Figs. 11 & 12)

Fig. 11

Fig. 12

Discussion

Missing teeth in the esthetic region negatively affect patient confidence, social behavior, and quality of life. The treatment of patients with missing teeth should be multidisciplinary. It can involve orthodontics, esthetic dentistry, implantology and prosthodontics.9 These patients must be managed with comprehensive interdisciplinary diagnostics and treatment planning. Teamwork and patient compliance can lead to highly successful treatment results.10

As this case demonstrates, complex diagnoses require the development and cooperation of an interdisciplinary team. In this case, the recognition of failure to achieve an ideal outcome with the first phase of orthodontic treatment demanded a treatment revision. Although treatment may be administered over a long period of time, and may not necessitate every multidisciplinary team member to be involved in every step of the process, it is essential that the treatment team follow the patient’s progress together. Following this guideline can help to ensure that an optimal outcome is achieved, and that the patient is satisfied with the results.

Oral Health welcomes this original article.

References

- Winkler, K.G. Boberick, S. Braid, R. Wood, M.J. Cari,” Implant Replacement of Congenitally Missing Lateral Incisors: A Case Report,” J Oral Implantol. 2008;34(2):115-8.

- Pini, N.I.P., Marchi, L.M., Pascotto, R.C., “Congenitally missing maxillary lateral incisors: update on the functional and esthetic parameters of patients treated with implants or space closure and teeth recontouring, “ Open Dent J. 2015 Jan6;8:28994.

- Alfallaj, H., “Pre-prosthetic orthodontics,” Saudi Dent J. 2020Jan;32(1):7-14.

- Jackson, BJ., Slavin, M.R., “Treatment of congenitally missing maxillary lateral incisors: an interdisciplinary approach,” J Oral Implantol . 2013Apr;39(2):187-92.

- American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Management of the developing dentition and occlusion in pediatric dentistry. The Reference Manual of Pediatric Dentistry. Chicago, Ill.: American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry;2021:408-25.

- Rana, S., Kelleher, M., “The Dangers of Social Media and Young Dental Patients’ Body Image,“ Dental Update 2018, Vol. 45, No.10

- Kunt, G.E., Ceylon, G., Yilmaz, N., “Effect of surface treatments on implant crown retention,” Journal of Dental Sciences, Volume 5, Issue 3, September 2010, Pages 131- 135

- Charasseangpaisarn, T., Krassanairawiwong, P., Sangkanchanavanich, C., Kurjirattikan, A., Kunyawatyuwapong, K., Tantivasin, N., “The Influence of Different Surface Cleansing Agents on Shear Bond Strength of Contaminated Lithium Disilicate Ceramic: An In Vitro Study,” Int J Dent. 2021 Aug 10; 2021:7112400.

- Almeida, R.R., Morandini, A.C., Almeida-Pedrin, R.R., Almeida, M.R., Castro, R.C., Insabralde, N.M., “A multidisciplinary treatment of congenitally missing maxillary lateral incisors: a 14-year follow-up case report,” J Appl Oral Sci. 2014SepOct;22(5):465-71.

- Jatol-Tekade, S., Tekade, S.A., Khetrapal, S., Sarode, S.C., Patil, S., ”Multidisciplinary approach to bilaterally missing lateral incisors: A case report,” Clin Pract. 2019Jan 29;9(1):1086.

About the Author

Kaveh Seyedan is Professor of Prosthodontics and Director, Postdoctoral Prosthodontics and Implants at Shahid Beheshti University, Tehran, Iran. Three-time past President, Iranian Association of Prosthodontists, he is Secretary General, Iranian Association of Implant Dentistry, Chair, Iranian Dental Association Science Committee, and Ambassador to the ICOI. He has authored 12 books and 70 papers on implants, ceramics, and the restoration of endodontically treated teeth.

Kaveh Seyedan is Professor of Prosthodontics and Director, Postdoctoral Prosthodontics and Implants at Shahid Beheshti University, Tehran, Iran. Three-time past President, Iranian Association of Prosthodontists, he is Secretary General, Iranian Association of Implant Dentistry, Chair, Iranian Dental Association Science Committee, and Ambassador to the ICOI. He has authored 12 books and 70 papers on implants, ceramics, and the restoration of endodontically treated teeth.