Dental wear is a general term that can be used to describe the surface loss of dental hard tissues from causes other than dental caries, trauma or as a result of developmental disorders. It is a normal physiological process that is macroscopically irreversible; Lambrechts et al.1 estimated the normal vertical loss of enamel from physiological wear to be approximately 20-38 μm per annum.

Due to the relatively slow pace and lack of symptoms with which this condition develops, patients are often not aware of the presence of a wearing dentition. Consequently, they often present for treatment at an advanced stage, complaining of an impairment of aesthetics and/or function.

Consequences of tooth wear include:2,3,4

- loss of vertical dimension of occlusion, which may result in dento-alveolar compensation or an increased inter-occlusal space at rest

- tooth sensitivity

- decreased oral health related quality of life

- aesthetic issues, as the position of the smile line, the horizontal occlusal plane and the incisal edge position

- loss of anterior guidance and canine protection, that may increase horizontal stresses on the posterior teeth.

Etiology of tooth wear:

The process of tooth wear has a multi- factorial aetiology; however, individual etiological factors may be subdivided into:

- Erosion

- Abrasion

- Abfraction

- Attrition

1. Erosion

Erosion is the loss of tooth surface by a chemical process that does not involve bacterial action.5 It is caused by the chronic exposure of dental hard tissues to acidic substrates which may be of an intrinsic or extrinsic source.

Erosive lesions typically manifest as bilateral concave defects without the chalkiness or roughness normally associated with bacterial acid decalcification. In its early stages, erosion affects the enamel layer, resulting in a shallow, smooth, glazed surface; after dentin exposure will occur. (Fig. 1) Evidence of “cupping” of both the occlusal surface of posterior teeth and incisal edges of the anterior teeth is usually found.6 (Fig. 2). Also, restorations may stand proud of the adjacent tooth surface.

Fig. 1

Fig. 2

occlusal of the posterior teeth.

Extrinsic erosion is often seen to occur on the labial surfaces of maxillary anterior teeth, typically in the form of scooped out depressions. (Fig. 3).7

Fig. 3

Extrinsic acid exposures can be caused by the consumption of acidic food (eg, citrus fruits, soft drinks, wine, salad dressings), acidic drugs (eg, acetylsalicylic acid, iron tablets, vitamin C supplements), as well as occupational acid exposure. (Table 1)7 The extent of dental hard tissue erosion is determined by the erosivity of the erosion-causing solution (pH, buffer capacity, and mineral concentration), and also by the frequency and type of consumption. Of course, the greater the amount of erosive products consumed per day, and the more often they are consumed, the greater the risk.

Table 1

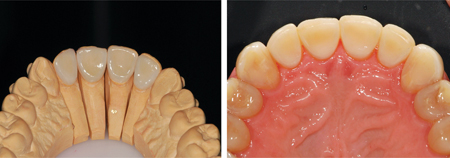

By contrast, intrinsic erosion is most often seen on the palatal surfaces of the maxillary anterior teeth and occlusal surface of the posterior teeth, resulting in a concave depression of the entire palatal surface. Often an intact ring of enamel is spared and remains present around the gingival area of the teeth; this enamel ring is probably due to the neutralization of the acid by the gingival crevicular fluid. Mandibular anterior teeth are relatively less affected by the process of erosion than the maxillary anterior dentition. Intrinsic erosion is caused by acidic gastric fluid coming into contact with the oral cavity, eg in patients suffering from bulimia (bulimia nervosa), gastroesophageal reflux disease, or alcohol abuse. The prevalence of dental erosion in reflux patients amounts to 17% to 68%. Conversely, 25% to 83% of all patients with erosion suffer from reflux.8 Since gastric fluid has a pH of around 1 and a high amount of free acid, its erosive potential is quite high.

2. Abrasion

Abrasion is the physical wear of tooth structure through an abnormal mechanical process independent of occlusion. A common cause of abrasion is the habit of overzealous tooth brushing. Lesions are typically rounded or ‘V’ shaped ditches seen on the buccal/labial surfaces in the region of the cemento-enamel junction. (Fig. 4) Notching of the incisal edges on maxillary central incisor teeth is often seen as a result of habits such as the biting of pins, tacks, nails.6

Fig. 4

3. Abfraction

Abfraction is the loss of hard tissue due to eccentric occlusal loads leading to compressive and tensile stresses at the cervical fulcrum area of the tooth. It usually manifests with the classical wedge-shaped defects with sharp rims at the cemento-enamel junction.6 (Fig. 5)

Fig. 5

4. Attrition

Attrition is the wearing away of tooth structure as a result of tooth-to-tooth contact, as in mastication, with possible abrasive substance intervention.5 It is most commonly observed to occur on the incisal and occlusal contacting surfaces.

Attrition is caused by the action of antagonistic teeth (e.g., grinding) and leads to matching facets; lesions typically are flat, sharp bordered, and glossy.

There is usually symmetry with an antagonist tooth but this is often in one of the border positions and frequently not in their habitual intercuspal position. The specific pattern of wear coincides with how and where the patient bruxes or rubs their teeth forcibly against one another during their parafunction.

The early clinical manifestation of attrition is the appearance of a small polished facet on a cusp or ridge, or the slight flattening of an incisal edge; as the lesion progresses, there is a tendency towards the reduction of the cusp height and flattening of the occlusal inclined planes, with concomitant dentine exposure.6 (Figs 6, 7, 8)

Fig. 6

stages, pulp chamber/root canal system might be visible.

Fig. 7

stages, pulp chamber/root canal system might be visible.

Fig. 8

stages, pulp chamber/root canal system might be visible.

Classification of tooth wear:

The pattern of tooth surface loss can be sub-classified into being either localized (anterior vs. posterior, with the latter, less common) or generalized tooth wear.

Usually, most common sites are the occlusal surfaces of the molars and the incisal edges of the anterior teeth.

Localized anterior wear:

Maxillary anterior teeth are most commonly involved in localized tooth wear, especially where erosion is a major factor. In the majority of patients, tooth wear is accompanied by dento-alveolar compensation which allows occlusal contacts to be maintained, in order to attempt to preserve the efficacy of the masticatory system.8 As this dental wear progresses and dento-alveolar compensation occurs, inadequate inter-occlusal prosthetic space develops between the upper and lower anterior teeth.

The decision on how to optimally restore these teeth will depend on the interplay between five factors: the pattern of anterior maxillary tooth surface loss, the inter-occlusal space availability, the space requirements of the dental restorations being proposed, the quantity and quality of available dental hard tissue, esthetic demands of the patient.9

Thus, to be able to restore the worn dentition 3 options are available:

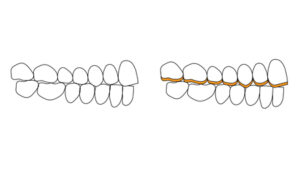

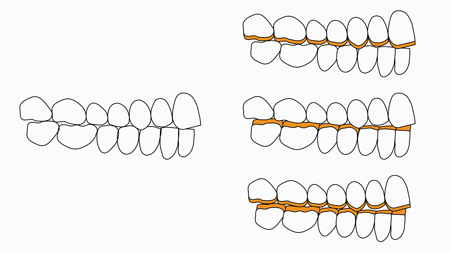

- Open VDO by restoring posterior teeth as well. This could involve only one arch or a combination of both arches. (Figs. 9, 10) The increase should be as minimal as possible to accommodate the recommended minimum thickness of the restorative materials planned

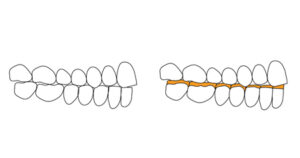

- Orthodontics – space at the anterior is achieved by intruding maxillary and/or mandibular teeth, followed by the restoration of the anterior teeth. (Fig. 11)

- Analysis of articulated diagnostic casts in centric relation may reveal an anterior slide from Centric Relation (CR) to Maximum Intercuspation Position (MIP). In these cases, an equilibration of the posterior teeth, if possible, can provide occlusal stability in centric relation and adequate restorative space for the anterior teeth.

Fig. 9

VDO needs to be increased and one of the 2 arches restored

Fig. 10

VDO needs to be increased and one of the 2 arches restored

Fig. 11

prosthetic space, is to orthodontically intrude and restore only the maxillary teeth. The posterior dentition will not require any treatment.

Case report #1 (Figs. 12 to 17)

Patient was concerned about the wear of her anterior teeth in the maxillary and mandibular arches. Etiology was mostly related to attrition as a consequence of a “constricted envelope of function”. The envelope of function is influenced by 2 factors: 1) the pathway of mandibular movement created by the contours of the teeth 2) The mandibular movement created by the patients own neuromuscular movement pattern.

Common dental signs of a “constricted envelope of function” (patients generally present with with relatively deep overbite and minimal overjet) includes:

- maxillary anterior palatal and incisal edge wear

- mandibular anterior incisal edge and labial wear

- anterior fremitus/mobility

- anterior diastema opening/flaring

- loosening or fracturing anterior provisionals/restorations (if any).

Simply put, the upper anterior teeth are “in the way” of the route that the mandible wants to follow during function. As a result, the wear is a consequence of creating a pathway for the antagonist mandibular anterior teeth. Unfortunately, being a slow process, there is continuous eruption of the affected teeth to compensate for the wear, leading to a lack of prosthetic space to restore the worn dentition. One of the treatment goals is to provide more overjet and/or less overbite to achieve the requisite space.

In this case, the maxillary posterior teeth were already restored with metal-ceramic crowns. Some of them presented with porcelain chipping and failing margins. The treatment plan included replacing the maxillary posterior crowns, placing new crowns on the maxillary anterior teeth, and restoring the mandibular anterior teeth with direct composite restorations.

A diagnostic wax-up (with a customized anterior guide table) was done at an increased VDO (Vertical Dimension of Occlusion) with the goal of increasing the overjet and reducing the overbite. This created adequate prosthetic space between the maxillary and mandibular anterior teeth. A significant benefit is the ability to restore the worn palatal aspect of the maxillary anterior teeth without the need for tooth reduction.

In these types of cases, it is important to perform a “trial therapy” with temporary restorations. Placing provisionals with the new shape and/or tooth position allows the patient to evaluate the interim restorations for function, phonetics and esthetics. If the provisionals show signs of wear/fracture or if the provisionals are de-cemented repeatedly during the trial therapy, then adjustments would need to be made. If there are no problems with the provisionals, then it can be assumed that they accommodate the patient’s neuromuscular envelope of function or movement pattern and they can be copied for the final restorations. Final restorations for this case were zirconia-layered crowns in the posterior teeth and E.Max© crowns in the anterior area from canine to canine. As mentioned before, the incisal edges of the mandibular anterior teeth were restored with direct composite. The patient was very pleased with the esthetic and functional result. A maxillary occlusal guard was provided upon completion of the reconstruction.

Fig. 12

anterior teeth.

Fig. 13

anterior teeth.

Fig. 14

anterior teeth.

Fig. 15

anterior teeth.

Fig. 16

anterior teeth.

Fig. 17

anterior teeth.

Case report #2

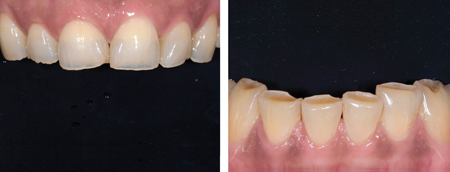

As the previous clinical case, also in this situation anterior dental wear was present. As clearly seen in the pictures, overtime, the wear has caused shortening of the maxillary anterior teeth, but no prosthetic space was available due, again to the continuous eruption of the affected teeth. (Figs 18, 19). An edge-to-edge occlusion was present between the maxillary and mandibular anterior teeth. In this situation, considering that the posterior teeth did not require restorations, we elected to treat the case with:

- orthodontic intrusion of the maxillary and mandibular anterior teeth and retraction of the lower ones (lower interproximal reduction (IPR) was required to allow for alignment and retraction of the lower incisors) with the goal of obtaining overjet and prosthetic space to restore the worn dentition

- restore teeth #14,13,23,25 with porcelain laminate veneers and #12,11,21,22 with “360°” veneers. Note that there was no palatal reduction of the maxillary incisors since the required space for the prosthetic material was obtained orthodontically.

Fig. 18

Fig. 19

After the orthodontic treatment was completed, a digital wax-up was done (Fig. 20), using the principles of “facially generated treatment planning”, as described by Spear10 and “digital smile design”, as described by Christian Coachman. Based on the wax-up, an intraoral mock-up was done to preview the esthetics (tooth length/size/shape, smile line), phonetics and obtain the patient’s approval before proceeding any further with treatment. Note that the intraoral mock-up can also be placed using a “spot-etch” bonding protocol so the patient has a trial period in order to evaluate the proposed restorations functionally and esthetically.

Fig. 20

In preparing the teeth for final restorations, the mock-up was also used as a “reduction guide” to allow for an ideal veneer preparation design which provided adequate reduction for the restorative material, while preserving tooth structure. A digital impression of the prepared teeth was taken together with pictures for final shade selection. Feldspathic restorations were fabricated and bonded according to the recommended protocol. The patient was pleased with the esthetic and functional outcome. (Figs. 21, 22)

Fig. 21

Fig. 22

Case report #3

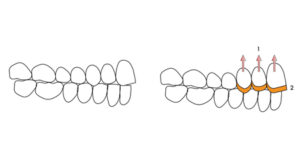

The pattern of localized anterior tooth wear for this patient was different in that there was palatal wear and no change in the length or buccal aspect of his anteriors was required. Orthodontic treatment was used to obtain prosthetic space and porcelain laminate veneers were fabricated to be applied only on the palatal aspect of the anterior teeth. (Figs. 23, 24)

Fig. 23

teeth. After orthodontic treatment was completed, light

preparation of the teeth was done for the insertion of veneers.

Fig. 24

the worn teeth. 2

Localized posterior wear:

Localized posterior wear is a far less common occurrence. Indirect restorations could be used to restore the occlusal surface of worn posterior teeth, but this will lead to an increase in the VDO. Consequently, the palatal aspect of the anterior teeth and/or the incisal edge of the mandibular will need to be restored to re-establish anterior guidance. The clinician must keep in mind that a rehabilitation must aim to provide a mutually protected occlusion through posterior disclusion and canine guidance.

Note also that advanced wear will lead to short clinical crowns and treatment may require a combination of endodontics and/or crown lengthening to place indirect restorations that will re-establish proper anatomy. In some instances, orthodontics may also be considered using TADs (Temporary Anchorage Devices) to intrude the posteriors.

Generalized wear:

Following an evaluation of the existing VDO, patients presenting with generalized wear may be assigned to three categories according to Turner and Missirlian:11

- Category 1 – excessive wear with loss of vertical dimension of occlusion

- Category 2 – excessive wear without loss of vertical dimension of occlusion, but with space available

- Category 3 – excessive wear without loss of vertical dimension, but with limited space.

The VDO can be evaluated according to several methods.12

In order to restore the worn dentition 3 possibilities exists: (Fig. 25)

- open VDO, as prosthetically as necessary, and restore the whole maxillary arch

- open VDO and restore the whole mandibular arch

- open VDO and restore both arches.

Fig. 25

of prosthetic space, the VDO needs to be increased and one or

both arches restored.

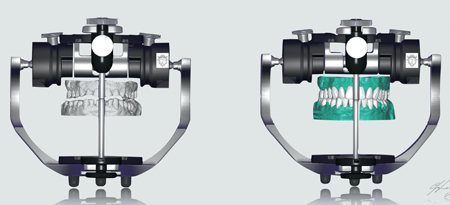

A set of diagnostic casts mounted in centric relation (CR) is strongly recommended. A diagnostic wax-up may be done traditionally with wax or digitally. This wax-up must restore esthetics and provide occlusal stability, based on the principles of mutually protective occlusal scheme, that consist of:13

- simultaneous stable bilateral tooth contacts

- centric relation (CR) coincident with centric occlusion (CO)

- disclusion of the posterior teeth, upon lateral and protrusive mandibular movements

- shared/even anterior guidance

- canine guided occlusion or with planned group function upon loss of canine guidance (or where the canine tooth may be unsuitable as a guiding unit), with the absence of working or non-working side occlusal interferences.

Using the diagnostic wax-up, temporary restorations are fabricated and the patient should be maintained in these provisionals for a period of 6-8 weeks.14 This time period will allow for an evaluation of the aesthetics and function, before the final restorations are fabricated and placed intra-orally.

One of the challenges of restoring worn dentition with indirect restorations (i.e. crowns) is to obtain sufficient abutment height. In fact, if this is lacking, the long-term success of restorations can be compromised leading to loss of cement seal and failure of the restoration. Thus, in this situations additional procedures, such as orthodontic extrusion and/or crown lengthening, might be required.

Case report #4

Patient presented with generalized dental wear; the aetiology was likely due to a combination of attrition and erosion. (Figs. 26, 27)

Fig. 26

The ethology was a combination of erosion (due to GERD)

and attrition.

Fig. 27

As the prevous case, the first step in this kind of rehabilitation is to mount a set of diagnostic casts in CR record. The mounted case was digitalized and a diagnostic wax-up was done, at an increased VDO. (Fig. 28) After the wax-up was reviewed and confirmed, a set of printed models were fabricated. Teeth were prepared and temporary restorations were placed; after period of 6-8 weeks, patient reported to be comfortable in the new occlusion and pleased with the aesthetics.

Fig. 28

and a diagnostic wax-up done.

Final restorations consisted of zirconia-layered crowns and E.Max© veneers in the mandibular anterior teeth. Full contour zirconia was selected on the occlusal surface of the posterior teeth with the goal of minimizing the chance of porcelain fracture/chipping due to the patient’s parafunctions. (Figs. 29, 30)

Fig. 29

Fig. 30

with the restorations. The patient was very pleased.

A maxillary occlusal guard was provided upon completion of the reconstruction, as it should be provided in these wear cases.

Case report #5

Historically, conventional restorative techniques (crowns and indirect restorations) have been the treatment for the management of tooth surface wear. In recent times, with improvements in adhesive technology and the availability of superior resin composites, adhesive retained restorations have become ever increasingly popular.15

The major disadvantages of conventional indirect restorations are:

- removal of tooth structure, which incur in risk of loss of pulp vitality overtime

- “irreversibility”: of course, when the tooth is prepared, there is no “going back”. In fact, according to a study by Edelhoff and Sorensen16, between 63% and 72% of coronal tooth tissue may be removed during the preparation of a tooth to receive an all-ceramic or porcelain fused to metal crown

- lack of adequate abutment height to allow for proper resistance and retention form which is required for long-term success. When not available, additional procedures may be required at further cost in terms of biology and finances

- cost.

Possible disadvantages of bonded restorations are:

- wear over time, especially when composite is used

- highly operative sensitive and require meticulous moisture control (usually rubber dam isolation should be the standard)

- require a good amount of tooth enamel to be successful.

Bonded adhesive restorations are, instead, more conservative in terms of tooth preparation and can be especially helpful when treatment needs to be phased due to financial or other treatment limitations.

In this case the patient presented generalized dental wear (Fig. 31); which required opening of the VDO to accommodate the restorative material. Due to financial limitations, direct bonded composite restorations were used to open the VDO and idealize the plane of occlusion. This facilitated the restoration of the anteriors with definitive porcelain restorations to ideal esthetics and function. The posterior composite restorations can eventually be replaced with porcelain restorations over time to complete treatment in a “segmented” fashion without compromising the ideal plane of occlusion, esthetics and function.1,7

Fig. 31

attrition

One of the challenges in restoring the posteriors with direct composite is in its application. Done free-hand, it is very difficult to achieve good occlusal contacts and anatomy at the desired VDO. To overcome this challenge, an ‘injection moulding” technique was used.

A diagnostic wax-up was done (Fig. 32) and clear polyvinylsiloxane (PVS) matrices were fabricated. A highly-filled flowable composite was injected through the matrix onto the worn surfaces using the appropriate bonding protocol, thereby accurately transferring the tooth anatomy and occlusal contacts at the proposed VDO. (Fig. 33) The accuracy of the wax up and a well-adapted matrix are critical to a successful outcome. It ensures that adequate quantities of material are applied onto worn surfaces without the inclusion of major voids and the clear matrix allows the composite resin to be light cured.

Fig. 32

Fig. 33

direct composite; thanks to the use of the clear matrices, the

restorations are an overall accurate “copy” of the wax-up.

An occlusal guard was given to the patient at the end of treatment and the patient was informed about the need for regular maintenance through polishing, repair and possible replacement. The patient was also reminded that these composite restorations are only a long-term temporary solution and that more durable ceramic restorations will be required in the future.

Conclusion

Restoration of the worn dentition presents a substantial challenge to the dental profession. Various modalities, including direct or indirect techniques, can be successful in the treatment of these patients. However, aside from the clinical treatment, other factors often need to be addressed. A diet of acidic foods and drinks, habits, parafunction and even other medical conditions can be significant. For example, for a patient whose wear is a result of intrinsic erosion due to acid reflux, referral to a physician or medical specialist is strongly advised. Hence, the treatment of dental wear requires a team approach to ensure general and dental health, and the longevity of the restorations, while providing great esthetic and functional results for the patient.

The importance of gaining informed consent when contemplating the active restorative management of a patient presenting with tooth wear cannot be overemphasized. It is vital that the patient understands the eventual restorative outcome, the scope of occlusal changes being planned, the limitation of currently available restorative materials and techniques, as well as the adaptation required to adjust to new restorations.

Oral Health welcomes this original article.

References

- Lambrechts P, Braeme M, Vuylsteke-Wauters M, Vanherle G. Quantitative in vivo wear of human enamel. J Dent Res 1989; 68: 1752–1754.

- Muts E, van Pelt H, Edelhoff D, Krejci I, Cune M. Tooth wear: a systematic review of treatment options. J of Prosth Dent 2014; 112:752-759.

- Dietschi D, Argente A. A comprehensive and conservative approach for the restoration of abrasion and erosion. Part I: concepts and clinical rationale for early intervention using adhesive techniques. Eur J Esthet Dent 2011;6:20-33.

- Davies SJ, Gray RJM, Qualtrough AJE. Management of tooth surface loss. Br Dent J 2002;192:11-23.

- Eccles J. Tooth surface loss from abrasion, attrition and erosion. Dent Update 1982; 9: 373–381.

- Mehta S, Banerji S, Millar B, Suarez-Feito J. Current concepts on the management of tooth wear: part 1. Assessment, treatment planning and strategies for the prevention and the passive management of tooth wear. Brit Dent J 2012; 212:1; 17-27.

- Kanzow P, Weghaust F, Attin T, Wiengard A. Etiology and pathogenesis of dental erosion. Quintessence Int 2016;47:275–278; doi: 10.3290/j.qi.a35625; originally published in Quintessenz 2015;66(9):1013–1017.

- Wilder-Smith CH, Materna A, Martig L, Lussi A. Gastro-oesophageal reflux is common in oligosymptomatic patients with dental erosion: a pH-impedance and endoscopic study. United Eur Gastroenterol J 2015;3:174–181.

- Mehta S, Banerji S, Millar B, Suarez-Feito J. Current concepts on the management of tooth wear: part 2. Active restorative care 1: the management of localised tooth wear. Brit Dent J 2012; 212:2; 73-82.

- Spear FM. Interdisciplinary Management of Worn Anterior Teeth. Facially Generated Treatment Planning. Dent Today. 2016 May;35(5):104-7.

- Turner K A, Missirilian D M. Restoration of the extremely worn dentition. J Prosthet Dent 1984; 52: 467–474.

- Fayz F, Eslami A. Determination of occlusal vertical dimension: a literature review. J Prosthet Dent. 1988 Mar;59(3):321-3.

- Stuart C, Stallard H. Concepts of occlusion. Dent Clin North Am 1963; 7: 591.

- Rivera-Morales W, Mohl N. Restoration of the vertical dimension of the occlusion in the severely worn dentition. Dent Clin North Am 1993; 36: 651–663.

- Mehta S, Banerji S, Millar B, Suarez-Feito J. Current concepts on the management of tooth wear: part 3. Active restorative care 2: the management of generalized tooth wear. Brit Dent J 2012; 212:3; 121-127.

- Edelhoff D, Sorensen J. Tooth structure removal associated with various preparation designs for anterior teeth. J Prosthet Dent 2002; 87: 503–509.

- Pin-Harry O. Prosthodontic Treatment of The Severely Worn Dentition. Oral Health Nov 2018.

About the Author

Dr. Mario Rotella is a board certified prosthodontist. He received his DDS from the University of Siena (Italy). After, he completed a 2-year Advance Education in General Dentistry program at the Eastman Institute for Oral Health, University of Rochester, Rochester, NY. At the same institution, he completed a 3-year Prosthodontic program. Dr. Rotella has presented his work in several dental meetings and he has, also, published several articles in peer-reviewed journals, such as the Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry. He maintains a full-time prosthodontic specialty practice in Toronto, Ontario.

Dr. Mario Rotella is a board certified prosthodontist. He received his DDS from the University of Siena (Italy). After, he completed a 2-year Advance Education in General Dentistry program at the Eastman Institute for Oral Health, University of Rochester, Rochester, NY. At the same institution, he completed a 3-year Prosthodontic program. Dr. Rotella has presented his work in several dental meetings and he has, also, published several articles in peer-reviewed journals, such as the Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry. He maintains a full-time prosthodontic specialty practice in Toronto, Ontario.