Abstract

This review focuses on the emerging field of chronotherapy in dentistry, which aims to optimize therapeutic efficacy and minimize adverse effects by administering drugs or interventions at specific times of the day based on the circadian clock’s modulation of physiological processes relevant to dentistry. It has been found from well conducted systematic reviews that chrono-radiotherapy and chrono-chemotherapy have reduced treatment side effects and improved therapeutic response, leading to higher survival rates in cancer patients. Additionally, animal studies suggest that the diurnal rhythm of tooth movement and periodontal tissue response to orthodontic forces may influence bone metabolism. Moreover, profound, and prolonged local anesthesia can be achieved when injected in the afternoon comparing to morning session, which may help the dentist in planning their appointments. The review will highlight the favorable outcomes of chronotherapy applications in dentistry, especially in head and neck cancer treatments, and identifies gaps in knowledge for future research. This review provides valuable insights for dentists and clinicians in optimizing therapeutic outcomes in their patients.

Circadian rhythms, integral to human biology with an approximately 24-hour cycle, intricately regulate major organ systems which in turn govern crucial physiological and metabolic processes.1,2 These rhythms extend their influence on factors profoundly relevant to dentistry, encompassing bone healing, immune responses, inflammation, and pain perception.1,2 The orchestration of these biological rhythms aligns our bodily functions with the natural day-night cycle, exerting a profound impact on overall physical and mental well-being.3 Disturbances in these circadian rhythms, termed circadian clock dysregulation, have emerged as implicated risk factors for a spectrum of diseases including cancer, diabetes, and neurodegeneration, underscoring the pivotal role of a healthy circadian rhythm.4-11

Circadian influence in oral tissue and oral Health: At the core of circadian rhythms lies a network of molecular pathways, including positive and negative transcription-translation feedback loops (TTFLs), orchestrating the expression of clock-controlled genes (CCGs).12 These pathways induce oscillations in clock genes, echoing a 24-hour cycle, in turn affecting behavioral and physiological processes.12 Key circadian elements such as CLOCK, NPAS2, BMAL1, PERIOD (PER1, PER2, PER3), CRYPTOCHROME (CRY1, CRY2), and retinoic acid-related orphan nuclear receptors (ROR) α/β/γ regulate circadian rhythms.13

Diverse oral tissues, including the gingiva, periodontal ligaments, salivary glands, and dental tissues, house circadian clock genes that play pivotal roles.14-17 The expression of core clock genes such as CLOCK, BMAL1, CRY1/2, and PER 1/2/3 in fibroblast cells of the gingiva and periodontal ligaments signifies their potential significance in periodontal health.18 Moreover, clock genes and proteins in salivary glands regulate fluid secretion, while dental tissues demonstrate circadian expression patterns during tooth development.19,20 Crucially, these rhythms extend their way to oral and craniofacial structures, contributing to the development, maintenance, and balance of oral health.21,22

A recent scoping review by the authors23 published in Chronobiology International Journal this year aimed to comprehensively chart the existing literature on chronotherapy in dentistry; it offers an encompassing perspective on the multifaceted applications of chronotherapy within the expansive realm of dentistry. The following are the main findings of this review.

Overview

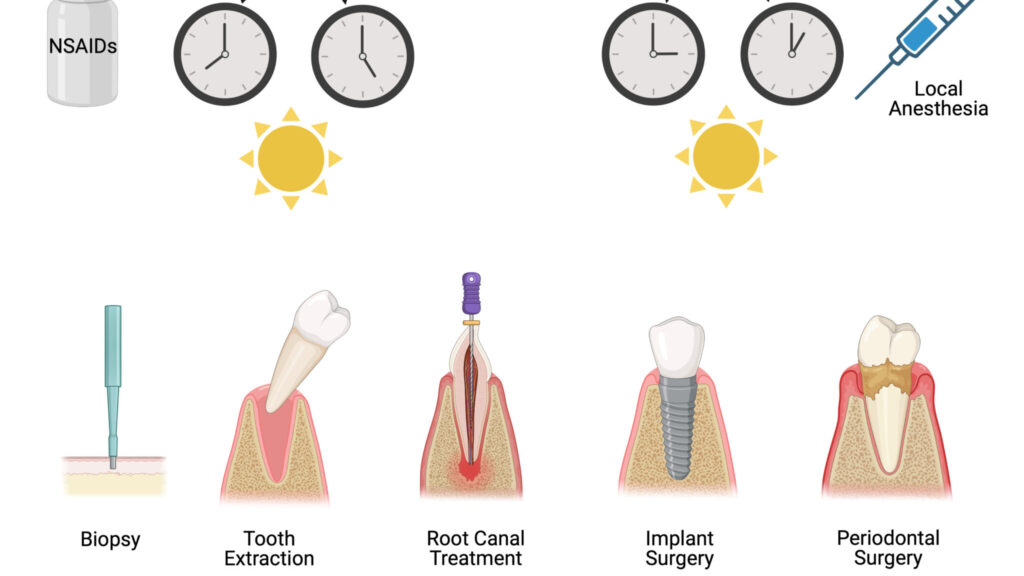

Twenty-four articles investigated chronotherapy in Dentistry. Included studies were categorized into five general research areas namely: chemotherapy and radiotherapy in head and neck cancer, orthodontics, local anesthesia, prosthodontics and oral medicine, and post-operative pain management and surgery. Figure 1 summarizes the best time for different dental interventions including all five research areas.

Fig. 1

Dental treatments and Chronotherapy

Chronotherapy, the science of timing medical treatments to the body’s natural circadian rhythms, has gained significant attention in recent years for its potential clinical applications, including benefits for general dentists. Dental implant placement is a critical procedure in restorative dentistry, and the timing of this procedure can play a crucial role in its success. Research has shown that chronotherapy can be applied to optimize dental implant placement by considering the circadian rhythms of bone metabolism.26 Bone turnover, which is essential for implant stability, follows a circadian pattern, with peak bone formation occurring during the late morning and early afternoon (Al-Waeli et al 2020). General dentists can utilize this knowledge to schedule implant surgeries during these optimal time frames, potentially leading to improved implant success rates and faster healing for their patients.

In addition to dental implant placement, the timing of medication administration is another area where chronotherapy can benefit general dentists and their patients. Many dental procedures involve post-operative pain management and antibiotic prescriptions. The circadian rhythms of the body can affect drug metabolism and absorption, influencing the effectiveness of medications. By aligning medication administration with the body’s natural rhythms, general dentists can potentially enhance the therapeutic effects of pain relievers and antibiotics, reducing the risk of side effects and improving patient comfort and recovery. For example, pain medications may be more effective when administered during the evening, as pain perception tends to be higher during the night. Overall, incorporating chronotherapy principles into dental practice can lead to better outcomes, improved patient satisfaction, and enhanced patient care in the field of dentistry.

Other applications of chronotherapy and dental treatment were investigated in different aspects such as:

Orthodontic tooth movement: Studies on rats (Igarashi et al. 1998, Miyoshi et al. 2001, Yamada et al. 2002) showed better outcomes restricting orthodontic forces to light periods (07:00 h−19:00 h) for faster tooth movement, enhanced bone formation, and reduced hyalinization. Mandibular retraction was more effective during the light period (08:00 h−20:00 h).

Local Anesthesia: Lemmer and Wie-mers (1989) and Pöllmann (1982) demonstrated optimal local anesthesia effect when injected at 14:00 h and 17:00 h.

Prosthodontics and Oral Medicine: Centric relation records showed circadian variation (Latta 1992); edentulous patients treated midday could mitigate changes. Waghmare and Puthenveetil (2021) found prednisolone at 06:00 h more effective for oral pemphigus vulgaris.

Post-operative Pain and Surgery: Tamimi et al. (2022) suggested daytime NSAID administration sufficient for third molar extraction pain control. Pérez-González et al. (2022) reported similar findings but in a different clinical trial design (not included in the review). Restrepo et al. (2020) found no correlation between surgery time and cleft lip and palate surgery complications.

Chrono-chemotherapy in head and neck cancer: Insights from clinical studies

Seven articles reviewed chrono-chemotherapy’s potential in head and neck cancer treatment. Studies indicated evening cisplatin administration reduced adverse effects. Animal and human trials showed improved survival rates, tumor response, and decreased immunosuppression with chrono-chemotherapy. Further research is needed for therapeutic optimization.

Chrono-radiotherapy in head and neck cancer: Interesting findings from animal and clinical studies

Animal Studies: Zhang et al. (2013) explored timing-dependent effects of topotecan (TPT) combined with radiotherapy in nasopharyngeal carcinoma mice. TPT administration at 15 HALO (active period) demonstrated superior tumor growth delay.

Human Studies: Retrospective studies by Gu et al. (2020) and Kuriakose et al. (2016) indicated morning radiotherapy correlated with lower radiation-induced oral mucositis. Brolese et al. (2021) found seasonal variation, not daytime, linked to mucositis severity. Elicin et al. (2021) revealed better outcomes with winter radiotherapy. Clinical trials including RCTs (Goyal et al. 2009, Bjarnason et al. 2009) and a non-RCT (Elzahi et al. 2020) supported reduced mucositis severity with morning radiotherapy.

What can we understand till now?

Chronotherapy holds promise for enhancing medical outcomes through timed interventions, aligning with circadian rhythms. In dentistry, potential benefits include optimized cancer treatment, extended local anesthesia effects, and improved post-operative recovery. Studies suggest timing influences orthodontic treatment effectiveness due to circadian bone physiology. Modifiers like age, sex, and lifestyle affect circadian rhythms but are often overlooked in studies. Incorporating circadian-based protocols and exploring clock-modulating molecules offer novel therapeutic avenues. Further research is needed to validate and expand the applications of chronotherapy in dental practice and beyond. Figure 2 shows proposed dental procedures that would benefit from chronotherapy of NSAIDs and local anesthesia.

Fig. 2

Overall, promising outcomes emerge from chronotherapy applications in dentistry. Evidence supports potential benefits of chrono-chemotherapy and chrono-radiotherapy for head and neck cancer, but standardized protocols are crucial. While orthodontic animal trials show promise, human trials are lacking. Prolonged local anesthesia in the afternoon holds potential, requiring further investigation. NSAIDs’ chronotherapy for post-operative pain control appears effective, demanding multicenter (Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) studies. The accuracy of centric records in complete denture fabrication process varies throughout the day, while surgery timing’s was not corelated to post-operative complications. Although evidence supporting chronotherapy in dentistry thus far is promising yet inconclusive, more clinical and experimental studies are needed.

Oral Health welcomes this original article.

References

- Al-Waeli, H., Nicolau, B., Stone, L. et al. Chronotherapy of Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs May Enhance Postoperative Recovery. Sci Rep 10, 468 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-57215-y.

- Chen S, Fuller KK, Dunlap JC, Loros JJ. 2020. A pro-and anti-inflammatory axis modulates the macrophage circadian clock. Front Immunol. 11:867. Crossref. PubMed. ISI.

- Dallmann R, Brown SA, Gachon F. 2014. Chronopharmacology: New insights and therapeutic implications. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 54:339–361. Crossref. PubMed. ISI.

- Reppert SM, Weaver DR. 2002. Coordination of circadian timing in mammals. Nature. 418:935–941. Crossref. PubMed. ISI.

- Bass J, Lazar MA. 2016. Circadian time signatures of fitness and disease. Science. 354:994–999. Crossref. PubMed. ISI.

- Fu L, Lee CC. 2003. The circadian clock: Pacemaker and tumour suppressor. Nat Rev Cancer. 3:350–361. Crossref. PubMed. ISI.

- Fu L, Lee CC. 2003. The circadian clock: Pacemaker and tumour suppressor. Nat Rev Cancer. 3:350–361. Crossref. PubMed. ISI.

- Hastings MH, Goedert M. 2013. Circadian clocks and neurodegenerative diseases: Time to aggregate? Curr Opin Neurobiol. 23:880–887. Crossref. PubMed. ISI.

- Marcheva B, Ramsey KM, Buhr ED, Kobayashi Y, Su H, Ko CH, Ivanova G, Omura C, Mo S, Vitaterna MH. 2010. Disruption of the clock components CLOCK and BMAL1 leads to hypoinsulinaemia and diabetes. Nature. 466:627–631. Crossref. PubMed. ISI.

- Panda S. 2016. Circadian physiology of metabolism. Science. 354:1008–1015. Crossref. PubMed. ISI.

- Parsons MJ, Moffitt TE, Gregory AM, Goldman-Mellor S, Nolan PM, Poulton R, Caspi A. 2015. Social jetlag, obesity and metabolic disorder: Investigation in a cohort study. Int J Obes. 39:842–848. Crossref. PubMed. ISI.

- Scheer FA, Hilton MF, Mantzoros CS, Shea SA. 2009. Adverse metabolic and cardiovascular consequences of circadian misalignment. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 106:4453–4458. Crossref. PubMed. ISI.

- Shilts J, Chen G, Hughey JJ. 2018. Evidence for widespread dysregulation of circadian clock progression in human cancer. PeerJ. 6:e4327. Crossref. PubMed. ISI.

- Battaglin F, Chan P, Pan Y, Soni S, Qu M, Spiller ER, Castanon S, Roussos Torres ET, Mumenthaler SM, Kay SA. 2021. Clocking cancer: the circadian clock as a target in cancer therapy. Oncogene. 40:3187–3200. Crossref. PubMed. ISI.

- Rahman S, Wittine K, Sedić

- M, Markova-Car EP. 2020. Small molecules targeting biological clock; a novel prospective for anti-cancer drugs. Molecules. 25:4937. Crossref. PubMed. ISI.

- Adeola HA, Papagerakis S, Papagerakis P. 2019. Systems biology approaches and precision oral health: A circadian clock perspective. Front Physiol. 10:399. Crossref. PubMed. ISI.

- Feng G, Zhao J, Peng J, Luo B, Zhang J, Chen L, Xu Z. 2022. Circadian clock — a promising scientific target in oral science. Front Physiol. 2388. Crossref.

- Janjic´ K, Agis H. 2019. Chronodentistry: The role & potential of molecular clocks in oral medicine. BMC Oral Health. 19:1–12. Crossref. PubMed. ISI.

- Papagerakis S, Zheng L, Schnell S, Sartor M, Somers E, Marder W, McAlpin B, Kim D, McHugh J, Papagerakis P. 2014. The circadian clock in oral health and diseases. J Dent Res. 93:27–35. Crossref. PubMed. ISI.

- Janjic´ K, Kurzmann C, Moritz A, Agis H. 2017. Expression of circadian core clock genes in fibroblasts of human gingiva and periodontal ligament is modulated by L-Mimosine and hypoxia in monolayer and spheroid cultures. Arch Oral Biol. 79:95–99. Crossref. PubMed. ISI.

- Zheng L, Seon Y, McHugh J, Papagerakis S, Papagerakis P. 2012. Clock genes show circadian rhythms in salivary glands. J Dent Res. 91:783–788. Crossref. PubMed. ISI.

- Zheng L, Papagerakis S, Schnell SD, Hoogerwerf WA, Papagerakis P. 2011. Expression of clock proteins in developing tooth. Gene Expr Patterns. 11:202–206. Crossref. PubMed. ISI.

- Adeola HA, Papagerakis S, Papagerakis P. 2019. Systems biology approaches and precision oral health: A circadian clock perspective. Front Physiol. 10:399. Crossref. PubMed. ISI.

- Feng G, Zhao J, Peng J, Luo B, Zhang J, Chen L, Xu Z. 2022. Circadian clock—a promising scientific target in oral science. Front Physiol. 2388. Crossref.

- Mohammad Abusamak, Mohammad Al-Tamimi, Haider Al-Waeli, Kawkab Tahboub, Wenji Cai, Martin Morris, Faleh Tamimi & Belinda Nicolau (2023) Chronotherapy in dentistry: A scoping review, Chronobiology International, 40:5, 684-697, DOI: 10.1080/07420528.2023.2200495.

- Okawa H, Egusa H, Nishimura I. Implications of the circadian clock in implant dentistry. Dental materials journal. 2020 Mar 27;39(2):173-80.

About the Authors

Dr. Haider Al-Waeli is a certified Periodontist, a Fellow of the Royal College of Dentists of Canada and works as an Assistant Professor at the Faculty of Dentistry Dalhousie University. He is also an Associate Periodontist in Park Lane Dental Perio Clinic in Halifax, Nova Scotia.

Dr. Mohammad Abu-Samak is a PhD Candidate at McGill University. His research interest is focused on chronotherapy in dentistry. Dr Abu-Samak is also a general dentist practicing in Vancouver and part-time clinical instructor at UBC.