keywords:

surgical root canal procedures, histopathology, biopsy,

non-endodontic

lesions, guidelines

Abstract

The aim of this study was to identify clinical parameters used by endodontists to determine the need for histopathological assessment of periapical tissues collected during surgical root canal procedures, the proportion of these tissues being biopsied, and if there is a need for established clinical guidelines to help the clinician decide whether tissues should be submitted for assessment or not. Endodontists practicing in Canada were invited to complete an anonymous electronic survey. Descriptive statistics and Chi square tests were performed to analyze the data. About one-third of endodontists registered with the Canadian Academy of Endodontics participated in the survey. While 53 percent of the respondents submitted all specimens for assessment, the remainder of the cohort cited that their decision to submit tissues for assessment depended on certain clinical parameters, such as appearance of the tissue, radiographic appearance and clinical history. The majority of endodontists felt that guidelines would be helpful in assisting them with the decision-making process when submitting tissues for histopathological assessment. There appears to be no consensus amongst endodontists in the management of tissues collected from the periapical area of teeth during endodontic surgical procedures, suggesting that more defined guidelines are required.

Introduction

Radiolucent lesions encountered in the periapical areas of teeth that have undergone either pulp necrosis or previous root canal treatment, are usually associated with the presence of infection in the root canal space. Although all modalities of root canal treatment are highly successful, post-treatment disease may occur and apical surgery may be necessary. A survey carried out in 2009 in the United States identified that 90 percent of endodontists were performing endodontic surgery within their practise.1 While their survey assessed certain clincian’s preferences and experiences in surgical endodontics, it did not approach the management of the tissues collected during the procedure.

Overall, periapical pathologies are being diagnosed primarily as periapical granulomas, abscesses or radicular cysts. However, non-endodontic processes such as central giant cell lesions, odontogenic keratocysts, ameloblastomas and malignancies, among others, can be associated with the apex of a tooth, and may account for a range of 1-10 percent of the apical diagnoses.2,3 The diagnosis of non-endodontic lesions is complex, and these lesions may present with radiographic features comparable to a periapical inflammatory lesion.4 As an example, odontogenic keratocysts can present in the periapical area up to 20 percent of the time.5 Solely, the radiographic appearance of a lesion cannot be used for its definitive diagnosis. It has been reported that neither size nor absence of lamina dura is adequate in determining a definitive diagnosis, necessitating a need for histopathological assessment for final diagnosis.6 It has been suggested that biopsy of tissue harvested from periapical lesions should be performed, in particular when lesions are large.2 The literature is not clear as to when tissues removed from the apical area during endodontic surgery should be submitted for biopsy.

The aims of this study were to: (a) investigate the clinical criteria that endodontists are utilizing to determine when tissue specimens are sent for histological assessment following surgical root canal procedures; (b) determine the number and proportion of specimens undergoing histopathological assessment, and (c) investigate the perceived need for established clinical guidelines.

Methods

This study was approved by the Health Sciences Research Ethics Board of Dalhousie University (REB: 2017-4231). A questionnaire was developed by an oral pathologist and an endodontist trained in separate dental institutions. The survey consisted of 11 questions, with 3 questions focused on clinician demographics (practise location, endodontic school attended, and number of years in practise), 2 questions pertained to number and frequency of surgical procedures completed, 3 questions regarding clinical parameters that guide management of surgical specimens, 2 questions regarding past clinical experiences with non-endodontic lesions and lastly, 1 question on the relative need for clinical guidelines. Questions included multiple choice items, some of which with open-ended options, and numeric rankings.

The survey was distributed electronically by the Canadian Academy of Endodontics (CAE) through a link to Opinio to all contacts in their database. CAE members consist primarily of endodontists in Canada.

Responses were anonymous and non-identifiable. The survey was open for responses for approximately 2 months, and then closed after a follow-up email was sent to the CAE membership contacts.

Data analysis was performed through SPSS statistics software. Descriptive frequencies were determined to analyze individual survey questions, and correlation statistics and chi-square tests were run where appropriate.

Participant Demographics

A total of 92 members (31 percent of registered CAE members) responded to the survey. Displayed in Table 1 are participant demographics collected from the survey.

Table 1

19% (n=18) of respondents working less than 5 years, 14% (n = 13) 5-10 years, 22% (n = 20) 11-20 years, 22% (n = 20) 20-30 years, and 23% (n = 22) over 30 years.

Discussion

This survey investigated the current practice of endodontists in Canada regarding submission of tissue for histopathological assessment when performing endodontic surgical procedures. A total of 31 percent of registered CAE members responded to the survey, representing a cross section of newly practising clinicians, to those with many years of experience. As a cohort, they cited graduate training and clinical experience to have the greatest effect on their decision-making process, although our results did not demonstrate any trends in terms of clinical behaviours based on training location or years of practise. The majority of the respondents completed their graduate training in the United States or elsewhere outside of Canada.

Tissue was submitted for biopsy regardless of clinical presentation by 53 percent of respondents. Not surprisingly, a significantly greater proportion of these practitioners had a previous experience with a non-endodontic lesion (Chi-square: X2 =7.218, df=2, p=0.027).

The respondents, who selected ‘clinical appearance of the tissue’ as the basis for whether to complete a biopsy, tended to credit their clinical experience as informing their decision-making, whereas those who reported submitting all tissue for biopsy, and those who based their decision on some other clinical parameter, tended to credit their graduate program with informing their decision-making (Chi-square: X2 =10.713, df=4, p=.03). It has been discussed in the literature that there is only weak agreement between clinical and histopathological diagnoses of periapical lesions obtained during endodontic surgery or from endodontically treated teeth that have been extracted.7 The differentiation between pathologies such as granulomas and radicular cysts may have minimal impact on prognosis following endodontic surgery, however, other possible diagnoses, such as odontogenic keratocyst, for instance, may require further management.

Although the number of respondents to this survey represents only 1/3 of registered endodontists in Canada, an important outcome in this study is that there is no concordance amongst practitioners in the management of tissue removed from the apical area during endodontic surgery. Of the respondents with a past experience of having dealt with non-endodontic lesions, 77 percent felt that it impacted their post-operative management of the patient.

Of the 45 respondents with a past clinical history of a non-endodontic lesion, 77.8% of them felt that this affected their post-operative management of the patient.

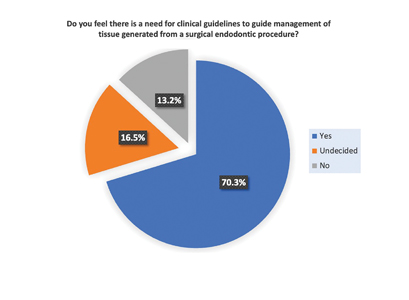

When asked if there is a need for clinical guidelines for management of tissue generated from an endodontic surgical procedure, only 16 percent of respondents did not feel a need for specific guidelines. Unfortunately, few guidelines or recommendations are available for the general dentist or dental specialist regarding the management of human tissues, likely due to the fact that inflammatory or infectious lesions represent the bulk of dental pathologies. Nevertheless, non-endodontic lesions do occur in the apical area of teeth, some as which have significant clinical consequences such as odontogenic keratocyst, ameloblastoma, central giant cell granuloma, lymphoma and metastatic diseases.9 Interestingly, the medical community has more established provincial guidelines across the country. An environmental report generated by the Canadian agency for drugs and technologies in health found that in general, pathological assessment is recommended for “all human tissue removed from a patient during an operation or curettage, excluding the following tissues: arm, hand, finger, leg, foot, toe, hemorrhoid, lens, prepuce, tonsil and tooth”.8 The foundation for this principle is based on the fact that malignancies can masquerade as benign or inflammatory processes both clinically and radiographically, making biopsy a definitive diagnostic tool.3 It is not rare that an oral lesion is the first manifestation of a malignant process and is detected before the primary malignancy in 30 percent to 66 percent of cases.10 Inadequate diagnosis of any of these entities allows for continued growth and destruction, and significant delay in appropriate definitive treatment.

Although root end surgery is a routine procedure in the endodontic office, it does not represent a large proportion of most endodontic practices; thus a simple solution to solve this conundrum may be to recommend that all samples be submitted for histopathological assessment, in keeping with half this study’s cohorts’ current practices.

Conclusions

This study investigated trends in management of periapical tissues during endodontic surgical procedures. There is no consensus among clinicians regarding their decision to submit tissue for histopathological evaluation, suggesting that clear guidelines would be advisable to assist clinicians with the most appropriate management of this issue.

Oral Health welcomes this original article.

References

- Creasy, J.E., P. Mines, and M. Sweet, Surgical trends among endodontists: the results of a web-based survey. J Endod, 2009. 35(1): p. 30-4.

- Kontogiannis, T.G., et al., Periapical lesions are not always a sequelae of pulpal necrosis: a retrospective study of 1521 biopsies. International Endodontic Journal, 2015. 48(1): p. 68-73.

- Koivisto, T., W.R. Bowles, and M. Rohrer, Frequency and Distribution of Radiolucent Jaw Lesions: A Retrospective Analysis of 9,723 Cases. Journal of Endodontics, 2012. 38(6): p. 729-732.

- Huang, H.Y., et al., Retrospective analysis of nonendodontic periapical lesions misdiagnosed as endodontic apical periodontitis lesions in a population of Taiwanese patients. Clin Oral Investig, 2016.

- Garlock, J.A., G.A. Pringle, and M.L. Hicks, The odontogenic keratocyst: a potential endodontic misdiagnosis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod, 1998. 85(4): p. 452-6.

- Caliskan, M.K., et al., Radiographic and histological evaluation of persistent periapical lesions associated with endodontic failures after apical microsurgery. International Endodontic Journal, 2016. 49(11): p. 1011-1019.

- Alotaibi, O., et al., Evaluation of concordance between clinical and histopathological diagnoses in periapical lesions of endodontic origin. J Dent Sci, 2020. 15(2): p. 132-135.

- Pitre, E., Routine Ordering of Primary Pathology Examinations in Canada, in Environmental Scan. 2014, Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health: Ottawa, CA.

- Ortega, A., et al., Nonendodontic periapical lesions: a retrospective study in Chile. Int Endod J, 2007. 40(5): p. 386-90.

- D’Silva, N.J., et al., Metastatic tumors in the jaws: a retrospective study of 114 cases. J Am Dent Assoc, 2006. 137(12): p. 1667-72.

About the Author

Lisa Johnson Assistant Professor, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Sciences, Faculty of Dentistry, Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS, Canada.

Lisa Johnson Assistant Professor, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Sciences, Faculty of Dentistry, Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS, Canada.

Isabel Mello Associate Professor, Department of Dental Clinical Sciences, Faculty of Dentistry, Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS, Canada.

Isabel Mello Associate Professor, Department of Dental Clinical Sciences, Faculty of Dentistry, Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS, Canada.