Orthodontic treatment can be described in 3 main groups based on the timing of treatment delivery as follows: 1) interceptive treatment, 2) comprehensive treatment, 3) adjunctive/limited treatment. Interceptive orthodontics describes orthodontic treatment that occurs during the mixed dentition stage of development. When interceptive treatment is done at the appropriate stage of growth and development (eg. 7-9 years of age), it results in the reduction of a patient’s case complexity and can negate the need for permanent tooth extraction(s) and/or orthognathic surgery in the future. The indications for interceptive orthodontics include treatment rendered to alleviate skeletal, dental and/or neuromuscular aberrations to reduce immediate malocclusion concerns (eg. spacing, crowding, open or deep bites, crossbites, severe or inadequate overjet, abnormal or altered eruption, space maintenance or acquisition, growth modification, eruption guidance, habit breaking).1,2 In most cases, interceptive treatment will be a first phase in a patient’s overall treatment journey and on occasion it may be effective enough to remove the need for a subsequent phase 2 comprehensive treatment.

In this article, 4 cases are presented where interceptive orthodontic treatment was undertaken to address dysplasia in the upper arch and correct an underlying dysplasia to reduce a patient’s overall case complexity.1,2 Each case was treated with a combination of a rapid palatal expander and braces from teeth 12-22. Since rapid palatal expanders can vary in design, (Fig. 1), their role in the biomechanics of each treatment plan differs. Additionally, each case was selected because mandibular treatment was not immediately undertaken as it was determined that this would occur at a future date if/when phase 2 comprehensive treatment would be pursued.

Fig. 1A

3. habit breaking, with posterior bite blocks.

Fig. 1B

3. habit breaking, with posterior bite blocks.

Fig. 1C

3. habit breaking, with posterior bite blocks.

CASE 1: Correction of antero-posterior maxillary dysplasia presenting as an underbite.

Summary:

This 8y-9m-old patient presented for treatment with a chief concern of an anterior cross bite (teeth 21, 22). Her initial occlusion was that of Class I molar relationship with a mild midline deviation. (Fig. 2) Cephalometric analysis (Fig. 3) revealed that her underbite was skeletal in nature (due to maxillary retrognathia) and that her upper incisors were in fact proclined, thereby camouflaging the degree of maxillary retrognathism.

Fig. 2

Fig. 3

Phase 1 interceptive treatment comprised of maxillary protraction with a banded rapid palatal expander and protraction facemask in combination with fixed edgewise appliances from teeth 12-22. (Fig. 4) Treatment duration was 12 months and resulted in a Class II molar occlusion with normalized overbite and overjet.

Fig. 4

Treatment considerations:

The use of a palatal expander allows for an increase in arch length following expansion and greater anchorage when correcting the maxillary incisor inclination.2,3

Incorporation of the protraction facemask corrects the underlying skeletal etiology (maxillary retrognathia) and avoids having the proclined upper incisors further proclined to correct the anterior crossbite. Furthermore, the maxilla was protracted into a Class II molar position in anticipation of future mandibular growth as the patient had a Class III skeletal growth pattern.

Facemasks are most successful if the treatment is completed before the age of 10. It should be worn 12-18 hours daily for 6-18 months and protraction force levels should range between 500-800g with consideration to the angulation of the protraction force from the facemask to support the opening or deepening of the bite as desired.3,4,5,6

Clinical relevance:

- Protraction of the maxilla results in the dentition sitting more anteriorly in the face resulting in an increased tooth show on smiling. (Fig. 5)

- This patient now demonstrates a normalized overbite and overjet with no crowding and the midline relationship is also improved. (Fig. 6) Depending of the growth direction and degree of antero-posterior dysplasia, overcorrection of the malocclusion into a Class II relationship with excess overjet may be of value as the Class III tendency can persist as the patient continues to mature.

- Monitoring of her remaining tooth eruption should be employed. In particular, the need for removal of 53 and 63 may be required to maintain a normal eruption sequence as teeth 13 and 23 are mesially positioned on the initial panoramic radiograph. (Fig. 7)

Fig. 5A

Fig. 5B

Fig. 6A

Fig. 6B

Fig. 7

CASE 2: Correction of vertical maxillary dysplasia presenting as an anterior open bite.

Summary:

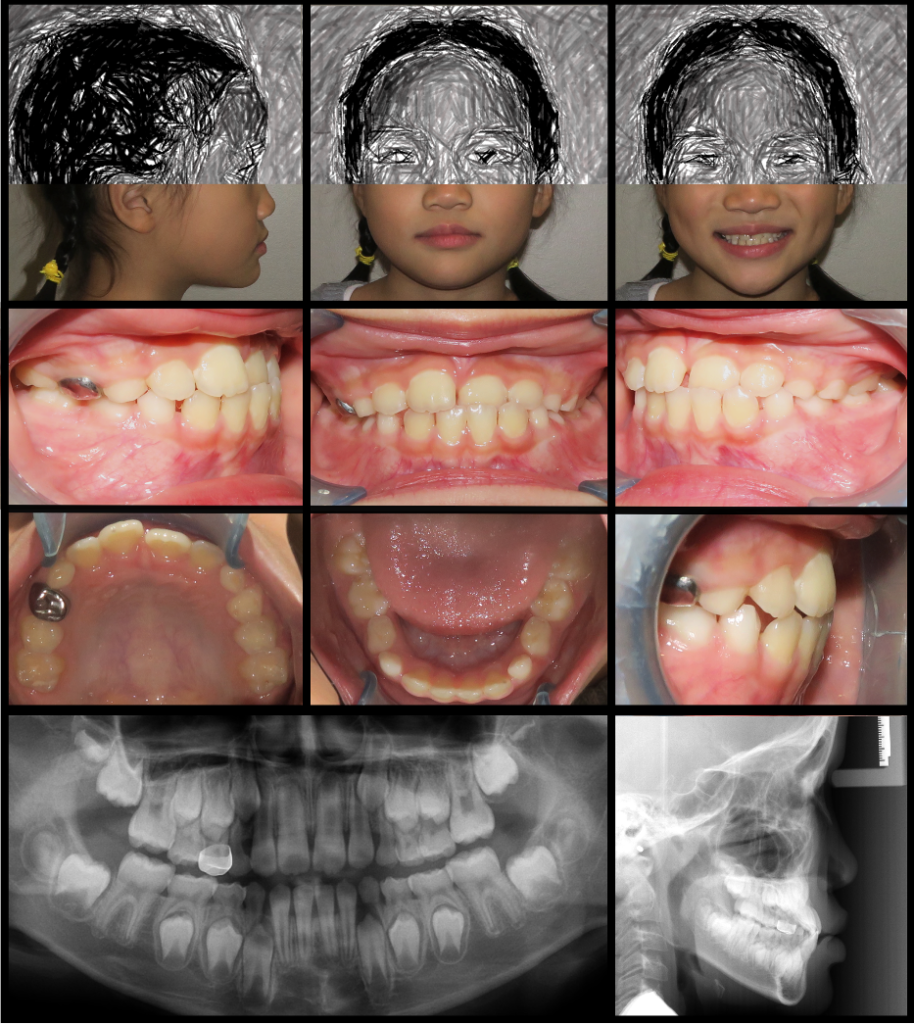

This 9y-3m-old patient presented for treatment seeking the correction of her anterior open bite secondary to tongue thrusting on swallowing habit. (Fig. 8) Dental analysis demonstrated a Class II molar relationship with a maxillary 2-plane occlusion and upper anterior spacing. Analysis of her lateral cephalogram determined that her open bite was associated with a steep mandibular plane and vertical growth direction, 2-planes of occlusion in the maxilla (due to reduced anterior vertical maxillary development and excessive posterior vertical maxillary development) and proclined maxillary incisors. (Fig. 9)

Fig. 8

Fig. 9

Phase 1 interceptive treatment comprised of a bonded rapid palatal expander with posterior bite blocks and tongue rakes in combination with fixed appliances from teeth 12-22. (Fig.10) Treatment duration was 12 months and resulted in a Class 1 molar occlusion with normalized overbite and overjet.

Fig. 10

Treatment considerations:

Identification and management of oral habits is crucial for long-term treatment outcome stability. It is common that patients with anterior open bites of tongue or finger etiology will also demonstrate maxillary constriction (secondary to soft tissue pressures from an open mouth posture and/or the pressure of buccinator muscles with persistent digit sucking) with or without dentoalveolar width changes in the mandibular arch.7

Use of a rapid palatal expander allows for the widening of the maxilla while the tongue rake assists in limiting any tongue protrusion that will prevent anterior bite closure.8,9

Incorporation of posterior bite blocks into the design of the palatal expander also allows for vertical control as this patient has a vertical growth pattern.10

Clinical relevance:

- Elimination of the 2-plane occlusion results in a harmonious and consonant smile arch and increased upper anterior tooth show. (Fig. 11)

- The benefits of managing of an anterior open bite at an early age is the elimination of a dual occlusal plane in the maxilla along with the functional gains of an anterior bite and the ability to pronounce sounds that are challenged by an anterior open bite (eg. ‘s’, ‘t’, ‘th’).

- Due to the mesial eruptive path of her permanent canines (more prominent in the maxilla), (Fig. 12) monitoring for guided eruption needs and directed extraction of teeth 53, 63 +/- 73, 83 at an appropriate time should be incorporated into this patient’s orthodontic treatment plan.

Fig. 11A

Fig. 11B

Fig. 12

CASE 3: Correction of horizontal maxillary dysplasia presenting as anterior crowding.

Summary:

This 8y-8m-old patient presented with a chief complaint of crowding. Key clinical findings included a Class II molar relationship, convex profile, a narrow maxilla with high palatal vault, upper and lower mild-moderate crowding with a lack of space for the eruption of teeth 12 and 22. (Fig. 13) Examination of the lateral cephalogram and panoramic radiograph confirmed mild mandibular retrognathia, that teeth 12 and 22 were not congenitally missing and that they were lingually inclined and would erupt into a second row of incisors (i.e. lingual to the central incisors) with a possible crossbite with the lower incisors.

Fig. 13

Phase 1 interceptive treatment comprised of a rapid palatal expander along with fixed edgewise appliances from teeth 12-22. (Fig. 14) Treatment duration was 12 months resulting class I molar relationship, inclusion of teeth 12 and 22 into the dental arch and prevention of teeth 12 and 22 lingual crossbite. (Fig 15)

Fig. 14

teeth 12-22.

Fig. 15A

Fig. 15B

Treatment considerations:

Fusion of the midpalatal suture is a progressive event that occurs as a patient moves through their adolescence and into adulthood.11 However, maxillary expansion without the aid of bone-anchorage or surgical assistance produces more effective skeletal (rather than dentoalveolar) changes when performed by or before the patient experiencing their major growth spurt.1,2,11

Clinical considerations:

- Correcting the horizontal dysplasia when lateral incisors are about to erupt allows for the correction of the malpositioned teeth 12 and 22 and prevailing crossbite.

- Future treatment should be considerate of the patient’s mandibular retrognathia and underlying Class II tendency.

CASE 4: Correction of maxillary vertical dysplasia presenting as a gummy smile

Summary:

This 8y-5m-old patient presented with a chief concern of a gummy smile. His class I malocclusion consisted of vertical maxillary excess and assoicated gummy smile along with moderate crowding in the upper and lower arches. (Fig. 16)

Fig. 16

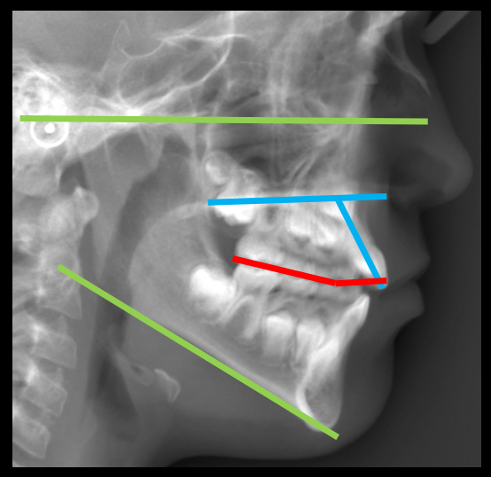

Analysis of his lateral caphogram confirmed a vertical growth direction with vertical maxillary excess and overerupted upper incisors. (Fig. 17)

Fig. 17

Interceptive treatment comprised of a bonded rapid palatal expander with posterior bite blocks and fixed edgewise appliances from teeth 12-22 (Fig. 18) and accompanying inctrusion arch mechanics. Treatment duration was 14 months, resulting in a class 1 molar relationship and a reduction in anterior gingival show. (Figs 19, 20)

Fig. 18

Fig. 19A

Fig. 19B

Fig. 20A

Fig. 20B

Treatment considerations:

Management of vertical maxillary excess in a growing patient allows the treating clinician to utilize remaining skeletal and dentoalveolar vertical development to alter the patient’s occlusal plane. In contrast, management of vertical maxillary excess in a non-growing patient is much more challenging, often involving treatment modalities such as temporary anchorage devices (TADs) or orthognathic surgery.

The rapid palatal expander with posterior bite blocks allowed for the widening of the maxilla with vertical control as well as alleviation of maxillary crowding as the arch is widened. Additionally, transpalatal anchorage provided adequate anchorage to permit the intrusion of the upper anterior teeth and associated periodontal structures. (see red arrows in Fig. 17)

Clinical relevance:

Intrusion of the upper incisors and upward movement of the associated periodontium results in improved smile arch esthetics and reduced the deep bite. (Fig. 19) Although the gingiva will migrate upwards as the teeth are intruded, residual gingival ‘bunching’ may occur. Options for a gingival procedure to manage any excess gingiva should take into consideration that the patient is still growing and delay of such procedure until vertical development is complete (adulthood) may be a preferred choice.

Discussion:

Interceptive orthodontic treatment allows for the reduction in overall case complexity by the decrease or elimination of skeletal, dental and or neuromuscular aberrations. Effective application of interceptive treatment relies upon the careful identification of the etiology of the malocclusion and a targeted approach to correct the areas of concern.1,2

In this article four cases of maxillary dysplasia (retrognathia, vertical deficiency, horizontal constriction, vertical excess) were shown and treated with the use of the rapid palatal expander (of various designs) in combination with anterior fixed edgewise appliances. These cases illustrated how a palatal expander is often used in combination with other force systems (both extra-oral and intra-oral) to impact changes in horizontal, antero-posterior and vertical dimensions. Integral to a successful delivery of these interceptive treatment plans is a timely application of treatment. In particular, maxillary protraction should be considered by 8 years of age and completed before 10 years of age as later attempts will yield reduced or no antero-posterior correction.3,4,5,6 Horizontal changes should be directed to the underlying etiology (skeletal and/or dentoalveolar). Where skeletal changes are desired, without implementation of bone anchorage or surgical assistance, palatal expansion can be considered as early as 7 years of age and preferably engaged by the time the patient is progressing through their pre-teenage/teenage growth spurt.2,11 When considering vertical changes, an appreciation of the vertical growth direction of the patient will assist in the appropriate design of appliances that will be used. Additionally, delivering this treatment after the eruption of incisors (i.e., around the age of 8 year of age) will allow the treating clinician to guide any future dentoalveolar and skeletal vertical development towards a move favourable outcome.2,7,8,9,10

Oral Health welcomes this original article.

References

- Mostafiz W. Fundamentals of Interceptive Orthodontics: Optimizing Dentofacial Growth and Development. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2019;40(3):149-154.

- Orthodontics: Current principles and techniques, sixth edition. Graber L.W.; Vanarsdall R.L; Vig K.W.L.; Huang G.J. Part 3, Chapter 16, 403-433.

- Kim JH, Viana M, Graber T, Omerza F, BeGole E. The effectiveness of protraction face mask therapy: A meta-analysis. AJO-DO 1999;115(6):675-685.

- Mandell N., Cousley R., DiBiase A., Dyer F., Littlewood S., Mattick R., Nute S., Doherty B., Stivaros N., McDowall R., Shargill, Ahmad A., Walsh T., Worthington H. Is early Class III protraction facemsk treatment effective? A multicentre, randomized, controlled trial: 3-year follow-up. J Orthod. 2012;39(3):176-85.

- Cordasco G., Matarese., Rustico L., Fastuca S., Caprioglio A., Lindauer SJ., Nucera. Efficacy of orthopedic treatment with protraction facemask on skeletal Class III malocclusion: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Orthod Craniofac Res. 2014; 17(3):1333-43.

- Woon SC., Thiruvenkatachari B. Early orthodontic treatment for Class III malocclusion: A systematic review and meta-analysis. AJO-DA 2017;151(1):28-52.

- Hsu B. The nature of arch width difference and palatal depth of the anterior open bite. AJO-DO. 1998;113(3):344-350.

- Canuto LFG., Janson G., Lima N., Almeida R., Cancado R., Anterior open-bite treatment with bonded vs conventional lingual spurs: A comparative study. AJO-DO. 2016;149(6):847-855.

- Iscan HN>, Sarisov L., Comparison of the effects of passive posterior bite blocks with different construction bites on the craniofacial and dentoalveolar structures. AJODO. 1997;112(2):171-8.

- Delllinger E. A clnical assessment of the Active Vertical Corrector – A nonsurgical alternative for skeletal open bite treatment. AJO-DO. 1986;86(5):428-436.

- Angelieri F., Lucia HS., Cevidanes LHS., Franchi L., Goncalves J., Benavides J., McNamara J. Midpalatal suture maturation: Classification method for individual assessment before rapid axillary expansion. AJO-DO. 2013;144(5): 759-69.

About the Author

Dr. Sean Chung completed his DMD (’09) and GPR (’10) at the University of British Columbia and MSc (Ortho), FRCD(C) (’13) at the University of Toronto. He maintains his private practise, North Toronto Orthodontists, and is an instructor in the Graduate Orthodontics and Pediatric Dentistry departments at the University of Toronto, Faculty of Dentistry. He can be reached at schung@NorthTorontoOrtho.com

Dr. Sean Chung completed his DMD (’09) and GPR (’10) at the University of British Columbia and MSc (Ortho), FRCD(C) (’13) at the University of Toronto. He maintains his private practise, North Toronto Orthodontists, and is an instructor in the Graduate Orthodontics and Pediatric Dentistry departments at the University of Toronto, Faculty of Dentistry. He can be reached at schung@NorthTorontoOrtho.com