Oropharyngeal cancers (OPCs) and oral cavity cancers are distinct head and neck cancers via location, causation, and incidence. OPCs encompasses the oropharynx structures – consisting of the mid-throat, the back one-third of the tongue, the soft palate, tonsils, and the side and back walls of the throat (Weatherspoon et al., 2015). Causally, OPC malignancies are mildly related to the consumption of alcohol and tobacco but are heavily correlated to the human papillomavirus (HPV) (Lechner et al., 2022). Figure 1 indicates all regions that the HPV virus targets on the human body of both sexes. It can be seen targeting the mouth and throat. Weatherspoon et al. (2015) discovered HPV in up to 80% of OPCs in North America and that HPV strain 16 forms 90% of HPV-positive OPCs. Incidentally, OPC cases have been rising alongside the rise of HPV. Habbous et al. (2017) found an increase in HPV-positive OPC cases in Canada, requiring a prevention strategy.

Fig. 1

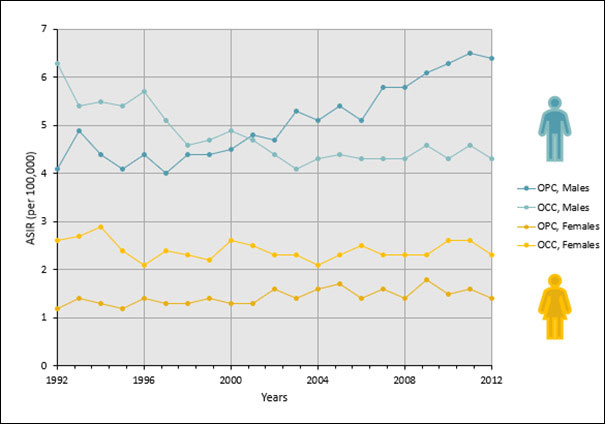

Research indicates that OPCs are 4.5 times higher in males compared to females, with females having higher vaccination rates (Office of the Chief Dental Officer of Canada, 2020). Figure 2 depicts this fact, showing the higher incidence of OPC in males compared to females and the decline of oral cavity cancer (OCC) incidence in males over the past few years. Research also indicates that in the past, testing in males with specific tumour stages of OPCs was higher compared to females. There has been a decrease in discrimination for testing between the sexes over the years; however, some residual bias may still exist (Habbous et al., 2017).

Fig. 2

The recognition of OPCs extends beyond diagnosis, staging, and treatment (Chu et al., 2013). It can bring about anxiety in patients. These anxieties arise from various factors – ranging from discomfiting discussions regarding sexually transmitted infections (STIs) like HPV, between patients and providers, to questions about HPV, which can be unanswerable due to insufficient studies or ambiguous results (Chu et al., 2013). To discern the primary cause of patient anxiety, Anderson et al. (2017) conducted research where primary care physicians (PCPs), Obstetricians/Gynecologists (OBGYNs) and Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgeons (OHNSs) in Canada completed an electronic questionnaire about counselling procedures involving HPV infection, transmission, and vaccination. The results concluded that the reason for PCPs not offering counselling was the general and personal scarce knowledge of OPCs.

Dentists contribute to detecting HPV-related OPCs at an early stage. A cross-sectional study by Sallam et al. (2019) found unfamiliarity among dental students, who were unable to diagnose HPV in the mouth. The poor diagnosis led to patients not being treated with early interventional techniques. In addition, the participants in the clinical group were reluctant to speak with patients about STIs and histories of sexual abuse. Aldossri et al. (2020) suggested that the lack of training in using oral cancer screening tools and addressing risk factors limits Ontario dentists’ ability to detect and prevent oral cancers. This is further supported by an article from Clarke et al. (2017), which concluded that only 64% of Canadian dental hygienists referenced cancer screening as part of their care. They found that only 43% of dental hygienists felt confident discussing HPV. A review article by Casey et al. (2022) also concluded that discussions on HPV were infrequent in the oral healthcare setting, relating it to oral healthcare professionals’ (HCP) lack of knowledge and communication skills.

As a result of these evident limitations, HCPs need to tackle patients’ concerns via accurate, informative, supportive, neutral, and non-stigmatizing counselling (Chu et al., 2013). Counselling should address ignorance regarding HPV-OPCs and should consist of an open, in-depth conversation on the facts of HPV-OPC, other HPV diseases, detection strategies, and vaccination (Chu et al., 2013). Improved training in oral cancer detection and readiness to identify and handle risk factors can help dentists detect and prevent oral cancers (Aldossri et al., 2020). Regarding immunization, Aldossri et al. (2021) found that dentists who possess comprehensive knowledge of HPV, are comfortable discussing sex-related topics, are willing to extend their scope of practice, and are more likely to recommend HPV immunization.

Regarding HPV immunization, Mark, A.M. (2023) found that the HPV vaccine can protect against more than 90% of HPV-related malignancies. 85% of people are estimated to have HPV infection at some point in their lifetime. The HPV virus disappears in many HPV-infected individuals. On occasion, however, the virus will conceal itself in the body and may result in cancer years after exposure. The vaccine is advised for children aged 11 to 12 by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the US. It can occasionally be administered to children as young as 9 years old to individuals as old as 26 years old. In fact, the Product Monograph for Gardasil-9 from Merck Canada recommends individuals aged 9 to 45 receive the nine-valent (Gardasil-9) vaccine. The vaccine will prevent HPV infection and oropharyngeal cancers from HPV types 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58.

Beyond immunization, improved counselling techniques and interprofessional collaboration between different HCPs could aid in preventing HPV-OPC and other HPV diseases. Kline et al. (2018) state that oral HCPs can reduce HPV-OPC through interprofessional collaboration by referring patients to relevant clinicians to receive vaccinations and any required follow-up. In addition, dentists can get involved in professional organizations with other HCPs to increase prevention efforts.

Unfortunately, a Canadian study submitted for publication by Gajic et al. found barriers preventing effective collaboration between dentistry and medicine. They found barriers such as the dysfunctional referral process, communication difficulties, disparities in patient insurance for medical and dental treatment, and a lack of education on interprofessional collaboration. They also found that there is a tradition of separation between dentistry and medicine at the educational level, leading to these barriers. They concluded that there should be further research on implementation techniques at the educational level for collaboration between HCPs. By doing so, teamwork in clinical practice may improve, and its effect on patient care regarding HPV-OPC can be better understood. The focus of this paper is to present an interprofessional approach to counselling patients on preventing HPV-OPCs. A family physician, gynecologist, pharmacist, and hospital dentist were individually interviewed, and guidance for dentists and the dental team is provided below.

Guidance from interviews

The interviewees were Dr. Marla Shapiro (family physician), Dr. Nancy Durand (gynecologist), Dr. John Papastergiou (pharmacist), and Dr. Deborah Saunders (hospital dentist). The experiences of discussing HPV-OPC among the HCPs shared many similarities. Discussions of HPV with their patients begin with facts about the virus, i.e., epidemiology, statistics, and HPV stereotypes for the two sexes and various age groups. Statements like, “HPV isn’t only a virus associated with the genital tract; it is also associated with the head and neck,” “HPV causes new cases of head and neck cancer more now than cases of cervical cancer,” and “the stereotype of the vaccine being for younger women is still very prevalent” were stated by Drs. Shapiro, Durand, and Papastergiou, respectively. They also discuss HPV-OPC vaccines: “Millions of doses have been given worldwide, it’s very safe,” says Dr. Papastergiou. “HPV is common to us all, 80% of Canadians will be exposed to HPV in their lifetime” and “HPV-associated cancers are the most preventable cancers” were stated by Dr. Saunders.

The HCPs also acknowledge the stigma surrounding the discussion of STIs, like HPV. They manage the stigma by placing less blame on the patient. Dr. Durand asserts, “I don’t initially say that it’s an STI. It’s a virus passed from person to person, so you’re already trying to decrease the blame.” To further this, the emphasis on what vaccination against HPV can provide should be at the forefront more than the mode of infection Dr. Saunders asserts. “Since HPV is common to all Canadians and protection using condoms is not effective, abstinence is not realistic in prevention, but vaccination is.” As dentists, our role in advocating and prescribing the vaccine is fundamental in preventing HPV-associated head and neck cancer. “We are the oral health care specialists. Oral care screening and addressing modifiable risk factors associated with oral disease is part of our vocation. This includes addressing diabetes management, oral hygiene, tobacco intervention, alcohol consumption, diet modifications, and HPV vaccination,” states Dr. Saunders.

As an interprofessional approach, the HCPs discussed barriers dentists should acknowledge when counselling patients. One common barrier included unfamiliarity among patients for present guidelines about HPV and vaccination. Dr. Durand states, “We don’t have an age limit in Canada for males and females for this vaccine. A lot of people don’t know that…The government offers to pay for it in school-based programs; it does not mean that the rest of us can’t be vaccinated; in fact, we should.” Additionally, Dr. Papastergiou mentions how he does not receive prescriptions or discuss HPV vaccines with dentists: “One of my best friends is a dentist, and I don’t think we’ve ever had that conversation ever, and we chat a lot.”

The experts discussed what guidance they would offer dentists. They agreed that dentists, counselling or not, should inform patients about HPV and the available vaccine opportunities. Examples include handouts, infographic posters, or having conversations where “the wording has to be pretty basic,” says Dr. Durand. Dr. Papastergiou implores dentists to: “Help with the messaging that we’re conveying as well. This is not a vaccine for an STD; this is a vaccine against cancer.” Moreover, dentists should inform patients to communicate with their primary care doctors about immunization strategies. Dr. Shapiro suggests, “Advise your patient: this is what I am looking for in your mouth. Have you talked to your doctor about vaccines that can prevent these changes? Because prevention can change your life.”

The HCPs all agreed that interprofessional collaboration is the best way to prevent HPV-OPC. Examples include collaborative education between dentists and other HCPs, as Dr. Shapiro suggested. Dr. Durand suggests, “A community practice where we get together four times a year, and it doesn’t have to be a get-together, just that ability to reach out when you’re not sure about something.” Different HCPs can also facilitate patients who do not have a primary care provider or insurance to reach dentists. Patients who visit dentists more frequently than other HCPs or vice versa are indicated in Table 1. It is evident from the data that various patient categories have difficulty in visiting and being counselled by dentists.

Table 1

| Description of patient | % of the type of health care professional attending patients based on their needs |

| Does not have a regular family physician/general practitioner. | Gynecologists (20% of USA patients view gynecologists as primary care physicians.)4 Otolaryngologists (N/A) Pharmacists (15% of Canadians.)24 Dentists (12.5% of US patients who were not HPV vaccinated had visited a dentist and not a family physician in the last year.)9 |

| Are counselled on HPV infection, transmission, and immunization. | Gynecologists (97% based on Canadian study.)3 Otolaryngologists (81% based on Canadian study.)3 Family physician (91% based on Canadian study.)3 Pharmacist (N/A) Dentists (Canadian dentists counsel on immunization specifically: 29.5%.)2 |

| Are recommended or are administered the HPV vaccine. | Gynecologists (57% of US gynecologists recommend.)4 Otolaryngologists (43% of US adolescents are recommended and administered.)29 Family physician (83% recommend and administer in Canada.)31 Pharmacists (51.6% recommend the vaccine across Canada;24 94% of Canadian pharmacists from Alberta administered the vaccine.)22 Dentists (20.5% of Canadian dentists recommend the vaccine;1 39% of dentists from a Canadian study said they should be able to administer HPV vaccines.)1 |

| Males recommended and have discussed the HPV vaccine with HCPs. | Gynecologist (21.2% of males aged 19-26 and 3.2% of males aged 27-45 based on US study.)17 Otolaryngologists (N/A) Family physician (66% recommend to males aged 11-12 years old based on US study.)15 Pharmacist (14% recommended to males from ages 11-26 based on US study.)11 Dentists (28% recommended to males from ages 11-26 based on US study.)11 |

| Females recommended and have discussed the HPV vaccine with HCPs. | Gynecologist (51.5% of females aged 19-26 and 15.8% of females aged 27-45 based on US study.)17 Otolaryngologists (N/A) Family physician (90% recommend to females ages ≥15 years old based on US study.)15 Pharmacist (17% recommended to females from ages 11-26 based on US study.)11 Dentists (31% recommended to females from ages 11-26 based on US study.)11 |

IMPLEMENTATION: Practical Strategies for Dentists

Dentists need practical strategies to treat, educate, and counsel patients on HPV-OPC. A qualitative study by Griner et al. (2019) examined dental opinion leaders’ perceptions of facilitators needed for the treatment, education, and counselling of patients on HPV-OPC, and, like the interviewed HCPs, they emphasized the significance of dental providers’ knowledge and training for answering questions and starting conversations. Their recommendations include training in motivational interviewing, talking points and scripts, role-playing, videos, and simulations. Additionally, they suggested counselling patients passively through pamphlets, posters in the office or waiting room, and educational campaigns. And a further strategy would be to increase private spaces. Casey et al. (2022) found that a barrier in the dental setting was the lack of private locations to have discussions.

Importance of healthcare provider recommendations

Papastergiou et al. (2021) found that of adult patients who received the HPV vaccination, only 62% received two injections and 37% received all three (completed regimen). This data indicates that there is a need for much improvement in vaccine adherence. Evidence suggests that HCP’s recommendation increases HPV vaccine uptake and can provide enhanced outcomes for vaccine adherence. Naavaal et al. (2023) found that dental care provider recommendations created positive perceptions of HPV vaccines. Steben et al. (2019) surveyed unvaccinated Canadian adults and discovered that recommendations from doctors motivated them to get vaccinated. Another paper by Rosenthal et al. (2011) concluded that women aged 19-26 who received a strong doctor’s recommendation rather than a weak one, had a 4x higher vaccination rate. This suggests that the strength of the recommendation also impacts vaccination uptake. Steben et al. (2019) discovered that knowledge from multiple sources was another motivator. It was concluded that doctors are the most reliable source, followed by nurses, and pharmacists; therefore, hearing the same message from various HCPs increases vaccine acceptance and uptake.

Conclusion

Preventing HPV-OPC requires acknowledging perceived barriers so that health care providers can take action. Based on this paper and additional studies, interprofessional collaboration is a means to increase patient access to education and thereby decrease the incidence of HPV-OPCs. In addition, it is promising that more and more dental team members are willing and able to present to patients a consistent message for prevention. Increasing collaboration can effectively prevent, diagnose, and treat patients through diverse knowledge from various HCPs and can improve vaccination access, uptake, and adherence.

Oral Health welcomes this original article.

References

- Aldossri, M., Okoronkwo, C., Dodd, V. J., Manson, H., & Singhal, S. (2021). Determinants of dentists’ readiness to assess HPV risk and recommend immunization: A transtheoretical model of change-based cross-sectional study of Ontario dentists. PLOS ONE, 16(2), e0247043. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0247043.

- Aldossri, M., Okoronkwo, C., Dodd, V. J., Manson, H., & Singhal, S. (2020). Dentists’ Capacity to Mitigate the Burden of Oral Cancers in Ontario, Canada. J Can Dent Assoc, 86. https://jcda.ca/sites/default/files/k1_0.pdf.

- Anderson, S., Isaac, A., Jeffery, C.C., Robinson, J.L., Isaac, D.M., Korownyk, C., Biron, V.L., & Seikaly, H. (2017). Practices regarding human Papillomavirus counseling and vaccination in head and neck cancer: a Canadian physician questionnaire. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 46(1), 61. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40463-017-0237- 8.

- Brennan, L.P., Rodriguez, N.M., Head, K.J., Zimet, G.D., & Kasting, M.L. (2022). Obstetrician/gynecologists’ HPV vaccination recommendations among women and girls 26 and younger. Prev Med Rep, 27, 101772. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2022.101772.

- Canadian Cancer Society’s Advisory. Committee on Cancer Statistics. Canadian Cancer Statistics 2016. Toronto, ON: Canadian Cancer Society; 2016.

- Casey, S. M., Paiva, T., Perkins, R. B., Villa, A., Murray, E. J. (2022). Could oral health care professionals help increase human papillomavirus vaccination rates by engaging patients in discussions? The Journal of the American Dental Association, 154(1). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adaj.2022.09.014.

- Chu, A., Genden, E., Posner, M., & Sikora, A. (2013). A Patient-Centered Approach to Counseling Patients With Head and Neck Cancer Undergoing Human Papillomavirus Testing: A Clinician’s Guide. The Oncologist, 18(2), 180-189. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0200.

- Clarke, A.K., Kobagi, N., & Yoon, M.N. (2018). Oral cancer screening practices of Canadian dental hygienists. Int J Dent Hyg. 16(2), e38-e45. doi: 10.1111/idh.12295.

- Cloidt, M., Kelly, A., Thakkar-Samtani, M., Tranby, E.P., Frantsve-Hawley, J., Shah, P.D., Laniado, N., & Badner, V. Identifying the Utility of Dental Providers in Human Papillomavirus Prevention Efforts: Results From the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2015-2018. J Adolesc Health, 70(4), 571-576. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.10.030.

- Coyne, M., Bergmann, H.V., Laronde, D., & Brondani, M.A. (2023). British Columbia Dentists’ Perceptions and Practices Regarding HPV Vaccinations: A Cross-sectional Study. J Can Dent Assoc, 89, n6. https://jcda.ca/n6.

- Fernandes, A., Wang, D., Domachowske, J.B., & Suryadevara, M. (2023). HPV vaccine knowledge, attitudes, and practices among New York State medical providers, dentists, and pharmacists. Hum Vaccin Immunother, 19(2), 219185. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2023.2219185.

- Gajic, E., Rao, M., Kirpalani, A., Colozza, S., & Dong, C.S. Understanding the Role of Interprofessional Collaboration in Managing HPV-Related Oropharyngeal Cancer. Submission in process.

- Griner, S.B., Thompson, E.L., Vamos, C.A., Chaturvedi, A.K., Vazquez-Otero, C., Merrell, L.K., Kline, N.S., & Daley, E.M. (2019). Dental opinion leaders’ perspectives on barriers and facilitators to HPV-related prevention. Hum Vaccin Immunother, 15(7-8), 1856-1862. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2019.1565261.

- Habbous, S., Chu, K. P., Lau, H., Schorr, M., Belayneh, M., Ha, M.N., Murray, S., O’Sullivan, B., Huang, S. H., Snow, S., Parliament, M., Hao, D., Cheung, W. Y., Xu, W., & Liu, G. (2017). Human papillomavirus in oropharyngeal cancer in Canada: analysis of 5 comprehensive cancer centres using multiple imputation. CMAJ, 89(32), E1030-E1040. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.161379.

- Kempe, A., O’Leary, S.T., Markowitz, L.E., Crane, L.A., Hurley, L.P., Brtnikova, M., Beaty, B.L., Meites, E., Stokley, S., & Lindley, M.C. (2019). HPV Vaccine Delivery Practices by Primary Care Physicians. Pediatrics, 144(4), e20191475. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1475.

- Kline, N., Vamos, C. A., Thompson, E. L., Catalanotto, F. A., Petrila, J., DeBate, R. D., Griner, S. B., Vázquez-Otero, C., Merrell, L., & Daley, E. M. (2018). Are dental providers the next line of HPV-related prevention? Providers’ perceived role and needs. Papillomavirus Research, 5, 104–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pvr.2018.03.002.

- Lake, P.W., Head, K.J., Christy, S.M., DeMaria, A.L., Thompson, E.L., Vadaparampil, S.T., Zimet, G.D., & Kasting, M.L. (2022). Association between patient characteristics and HPV vaccination recommendation for postpartum patients: A national survey of Obstetrician/Gynecologists. Prev Med Rep, 27, 101801. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2022.101801.

- Lechner, M., Liu, J., Masterson, L., & Fenton, T.R. (2022). HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancer: epidemiology, molecular biology and clinical management. Nat Rev Clin Oncol, 19(5), 306-327. doi: 10.1038/s41571-022-00603-7.

- Mark, A.M. (2023). Heading off cancer with a vaccine. The Journal of the American Dental Association, 154 (8), 774. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adaj.2023.06.001.

- Merck Canada. (2022, April 6). PRODUCT MONOGRAPH INCLUDING PATIENT MEDICATION INFORMATION GARDASIL®9 [Human Papillomavirus 9-valent Vaccine, Recombinant]. Retrieved on 2023, May 19 from https://www.merck.ca/en/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/2021/04/GARDASIL_9-PM_E.pdf.

- Naavaal, S., Demopoulos, C. A., Kelly, A., Tranby, E., & Frantsve-Hawley, J. (2023). Perceptions about human papillomavirus vaccine and oropharyngeal cancers, and the role of dental care providers in human papillomavirus prevention among US adults. The Journal of the American Dental Association, 154(4), 321–329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adaj.2022.12.006.

- Navarrete, J., Hughes, C.A., Yuksel, N., Schindel, T.J., Makowsky, M.J., & Yamamura, S. (2022). Community pharmacists’ provision of sexual and reproductive health services: A cross-sectional study in Alberta, Canada. Journal of the American Pharmacists Association, 62 (4), 1214-1223, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.japh.2022.01.018.

- Office of the Chief Dental Officer of Canada. (2020). Human papillomavirus and oral health. Can Commun Dis Rep, 46(11/12), 380-383. https://doi.org/10.14745/ccdr.v46i1112a03.

- Our Care, (n.d.). “Those without a family doctor or NP: If you have a regular health care provider, is the person you usually talk to a….?” Retrieved on 2023, July 26 from https://data.ourcare.ca/those-without-primary-care.

- Papastergiou, J., Smiley, T., & Donnelly, M. (2021). Factors Affecting Pharmacist-Administered Vaccine Injection and Adherence Rates in Canada. Int J Pharm, 11(9), 3-9.

- Polla, G.D., Napolitano, F., Pelullo, C.P., Simone, C.D., Lambiase, C., & Angelill, I.F. (2020). Investigating knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding vaccinations of community pharmacists in Italy. Hum Vaccin Immunother, 16(10), 2422-2428. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2020.1720441.

- Rosenthal, S.L., Weiss, T.W., Zimet, G.D., Ma, L., Good, M.B., & Vichnin, M.D. (2011). Predictors of HPV vaccine uptake among women aged 19-26: importance of a physician’s recommendation. Vaccine, 29(5), 890-895. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.12.063.

- Sallam, M., Al-Fraihat, E., Dababseh, D. et al. (2019). Dental students’ awareness and attitudes toward HPV-related oral cancer: a cross sectional study at the University of Jordan. BMC Oral Health, 19, 171. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-019-0864-8.

- Shew, M., Shew, M.L., & Bur, A.M. (2019). Otolaryngologists and their role in vaccination for prevention of HPV associated head & neck cancer. Hum Vaccin Immunother, 15(7-8), 1929-1934. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2018.1526559.

- Steben, M., Durand, N., Guichon, J.R., Greenwald, Z.R., McFaul, S., & Blake, J. (2019). A National Survey of Canadian Adults on HPV: Knowledge, Attitudes, and Barriers to the HPV Vaccine. J Obstet Gynaecol Can, 41(8), 1125-1133.e6. doi:10.1016/j.jogc.2019.05.005.

- Steben, M., Durand, N., Guichon, J.R., Greenwald, Z.R., McFaul, S., & Blake, J. (2019). A National Survey of Canadian Physicians on HPV: Knowledge, Barriers, and Preventive Practices. J Obstet Gynaecol Can, 41(5), 599-607.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jogc.2018.09.016.

- Weatherspoon, D.J., Chattopadhyay, A., Boroumand, S., & Garcia, I. Oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancer incidence trends and disparities in the United States: 2000-2010. (2015). Cancer Epidemiol, 39(4), 497-504. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2015.04.007.

About the Authors:

Dr. Cecilia Dong is an Assistant Professor at Western University’s Schulich School of Medicine and Dentistry, and cross-appointed to the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine.

Dr. Nancy Durand is an Associate Professor at University of Toronto in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. She focuses on preventing HPV-related diseases.

Dr. Marla Shapiro is a professor at the University of Toronto’s Department of Family and Community Medicine, and a Canadian public health journalist.

Dr. John Papastergiou is a Community Pharmacist and Adjunct Assistant Professor at the Schools of Pharmacy at the Universities of Waterloo and Toronto.

Dr. Deborah Saunders is a Hospital Dentist, an Associate Professor at the Northern Ontario School of Medicine, and a Medical Director.

Javeria Ahmed is a third-year undergraduate studying Honours Life Science at McMaster University and aspires to become a healthcare professional in the future.