Life-threatening hemorrhage following oral surgical procedures, including the placement of dental implants and tooth extractions has been reported in numerous case reports and literature reviews.1–7 Although infrequent, profuse hemorrhage is a significant complication that clinicians performing oral surgical procedures may encounter and subsequently need to manage.8 The complex and often variable anatomy of the floor of mouth (FOM), mandible, and surrounding facial structures play a crucial role in the etiology of such hemorrhagic events. A thorough understanding of the regional anatomy, mechanisms of injury, and hemorrhage management strategies is critical in preventing adverse outcomes. Three case reports of life-threatening hemorrhage following dental implant surgery and third molar removal are reviewed. Pertinent anatomy and appropriate surgical and medical management strategies are then discussed.

Case 1

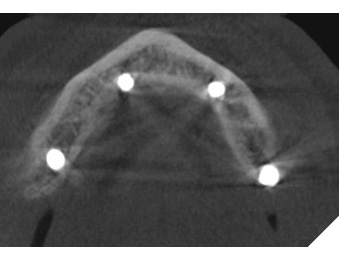

A 49-year-old male patient was referred to an oral and maxillofacial surgeon (OMFS) due to bleeding from the FOM that occurred while placing four mandibular implants in an edentulous mandible (Figs. 1 & 2). The patient’s past medical history was significant for insulin-dependent diabetes, hypertension and dyslipidemia. As per the initial dentist’s report, rapid bleeding occurred from the FOM while placing an implant in the right anterior mandible. The bleeding was able to be temporarily controlled with firm pressure in the right FOM.

Fig. 1

Fig. 2

On presentation to OMFS, the FOM was examined and brisk, rapid bleeding that appeared to be of arterial origin was noted. Local anesthesia with epinephrine was administered into the area. A distal branch of the lingual artery was noted to be transected; the distal end was visualized and ligated with 3-0 silk suture. Bleeding from the surrounding musculature was controlled with electrocautery. The proximal end of the vessel was not easily identified but there was no further brisk bleeding appreciated. It was estimated that the patient’s blood loss exceeded 500cc. While acute hemorrhage control was being performed, intravenous (IV) access was obtained, and vitals were monitored. The patient was tachycardic with a heart rate (HR) ranging from 105 to 110 bpm but was otherwise stable. Following acute hemorrhage management, the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) for one-on-one care to observe for any additional bleeding and for fluid resuscitation as required. The patient’s hemoglobin (Hb) was 120 g/L from a baseline of 150-170 g/L and no blood transfusion was required.

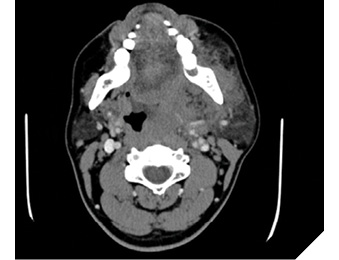

Approximately 5-6 hours after the initial event, the patient was noted to have an expansile hematoma of the FOM which was associated with signs of upper airway obstruction (Fig. 3); tripoding and dysphagia, and a muffled voice. On clinical exam, it was determined that immediate bedside intervention was not required and that transfer to the operating room (OR) for further management was the most appropriate course of action.

Fig. 3

In the OR, a difficult airway was anticipated, and the plan was to secure the airway with an awake nasal fibreoptic intubation. The patient was prepared for a tracheostomy in the event of a failed intubation. The patient was successfully intubated and once the airway was secured, the hematoma was evacuated. Bleeding was noted to be arising from deeper within the FOM. The proximal end of the sublingual artery was located and ligated with a 3-0 silk suture. Bleeding from surrounding musculature was again controlled with electrocautery. The site was noted to be hemostatic, but the patient was left intubated in the ICU for continued observation. There was no further bleeding, and the patient was extubated the following day and discharged home in stable condition.

Case 2

An otherwise healthy 32-year-old male was urgently referred to the emergency department (ED) after extraction of tooth 38. The extraction was completed earlier in the morning uneventfully. The patient returned to the dentist’s office in the afternoon for ongoing bleeding from site 38 and additional sutures were placed for hemostasis. Shortly after the patient developed dysphagia and odynophagia and was directed to the ED.

On clinical examination in the ED, the patient was vitally stable and on room air. The patient was drooling and unable to swallow his saliva. Maximum incisal opening was 25mm. There was a large hematoma in the left oropharynx with significant ecchymosis and deviation of the uvula to contralateral side. The extraction sites appeared to be hemostatic on clinical examination. The FOM was soft and non-elevated. A computed tomography (CT) neck, chest x-ray (CXR) and electrocardiogram (ECG) were ordered and IV fluids, tranexamic acid (TXA) and dexamethasone were started. During these investigations, bleeding was noted and approximately 300cc of blood was suctioned from the oral cavity.

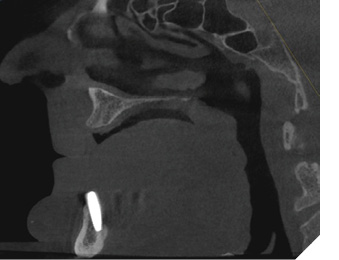

The CXR and ECG were unremarkable. The CT neck demonstrated an alveolar fracture at site 38 with significant hematoma in the left oropharyngeal region with airway deviation (Fig. 4). There was also extensive perimandibular subcutaneous air visualized.

Fig. 4

The patient was urgently taken to the OR for exploration and hematoma evacuation. An awake intubation with topical measures was successfully completed to secure the airway. Sutures were released from site 38 and pulsatile arterial bleeding was encountered. Under adequate visualization, the hemorrhage was noted to be coming from the buccal apex of extraction site 38, consistent with an inferior alveolar arterial bleed. Local measures failed to adequately control the hemorrhage. Electrocautery was then used carefully to successfully control the bleeding. Bone wax was then applied at the apex of site 38. After controlling the hemorrhage, hematoma evacuation was completed. Multiple clots were removed from the bilateral parapharyngeal and lateral pharyngeal spaces. All sites were irrigated thoroughly. A fractured lingual plate was then visualized and removed with care to preserve the intact lingual nerve. The patient remained intubated and was transferred to ICU in stable condition for continued monitoring. He was extubated on post-operative day (POD) 1 and discharged home on POD 3. The presentation and intra-operative findings were consistent with an inferior alveolar artery bleed extending into the parapharyngeal spaces through a lingual plate fracture resulting in airway compromise.

Case 3

An otherwise healthy 24-year-old male presented to a community hospital for persistent bleeding following extraction of teeth 28 and 38 (Fig. 5). Hb was 89 g/L from a baseline of 120 g/L. The patient was admitted overnight, and the bleeding was managed adequately with local measures and IV TXA. Upon discharge, the patient was sent to an OMFS for a presumed “liver clot” at site 38. During assessment, uncontrollable brisk arterial bleeding was encountered from the left posterior mandible. The site was packed, pressure applied, and the patient was transported to the ED via ambulance with concerns for hypotensive shock. The on call OMFS team and ED was notified. On presentation to the ED, the patient was pale, diaphoretic and cool to touch. He was hypotensive (MAP 60-65 mmHg), tachycardic (140-150 bpm) and tachypneic with normal oxygen saturation on room air. Hb was 72 g/L, blood lactate 4.0 mmol/L and blood pH 7.26. Large bore IVs were inserted bilaterally, aggressive IV fluid resuscitation was started and IV TXA was administered. Warming was applied to prevent further hypothermia. The OR team and the anaesthesia team was notified for an emergency OR.

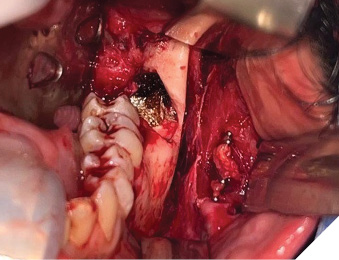

Fig. 5

The patient continued to occlude on gauze and was transported to OR for exploration of the left mandible and hemorrhage control. A rapid sequence oral intubation was successfully carried out by anaesthesia. It is important to note that profuse hemorrhage was encountered during intubation. Once the airway was secured, the surgical team rapidly isolated the source of bleeding to prevent further hypotensive shock. Given the patient’s hemodynamic instability, 2 units of packed red blood cells (pRBCs) were administered immediately. Sutures were released and the incision at site 38 was extended anteriorly for wider exposure. In addition to gauze pressure, two Yankauer suctions were required to maintain adequate visualization. Bleeding was noted to be arising from the soft tissues lateral to the site 38. A large vessel deep in the soft tissues was isolated and occluded with a mosquito hemostat. Hemostasis was achieved and the vessel was further dissected proximally and distally. Four medium size vascular clips were applied, and the hemostat was released from the vessel presumed to be the facial artery (Fig. 6). The sites were irrigated, gelfoam was placed at site 38, and the incision was closed primarily. The patient was extubated in the OR and transferred to ICU for monitoring due to ongoing hemodynamic instability. The presentation and intra-operative findings were consistent with a supraperiosteal bleed from the left facial artery resulting in hypotensive shock.

Fig. 6

Review of anatomy

The hard and soft tissues of the maxillomandibular region have a rich collateral blood supply arising primarily from the external carotid artery (ECA) both ipsilaterally and contralaterally. Consequently, even with cautery, ligation, or embolization, these vessels have the potential to regain blood flow in a short amount of time.

The ECA branches from the common carotid artery at the level of the upper border of the thyroid cartilage. The eight branches of the ECA from inferior to superior include the superior thyroid, ascending pharyngeal, lingual, facial, occipital, posterior auricular, internal maxillary, and superficial temporal arteries. The inferior alveolar, facial, and lingual arteries are of particular relevance to implant surgery and third molar removal.9

The lingual artery ascends from the ECA and passes deep to the hyoglossus muscle to enter the FOM. The four main lingual arterial branches include the suprahyoid artery, sublingual artery, dorsal lingual artery and, most terminally, the deep lingual artery. The dorsal lingual artery supplies the root of the tongue and the palatine tonsils, while the deep lingual artery supplies the lingual body of the tongue. The sublingual artery is the main blood supply to structures in the FOM, including the sublingual gland, mylohyoid muscle and mandibular gingiva. The anterior mandible is particularly susceptible to accidental lingual perforation and subsequent hemorrhage during implant surgery due to the close proximity between FOM vessels and the lingual cortical plate, especially if mandibular atrophy is present.6 Furthermore, vessels from either the sublingual branch of the lingual artery or the submental branch of the facial artery can perforate through the lingual cortex of the mandible and be possible sources of bleeding. This should be considered in the placement of the dental implants in the anterior mandible and when dissecting lingual tissues. Damage to vessels in this area that is not identified and controlled during surgery may present as hematoma formation in the post-operative period.

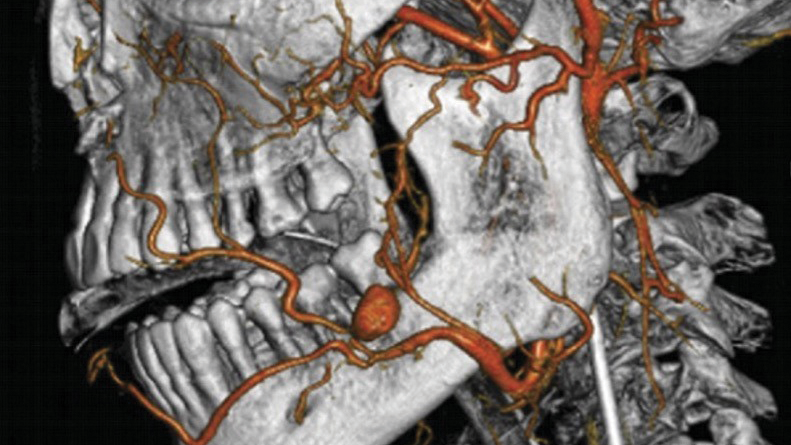

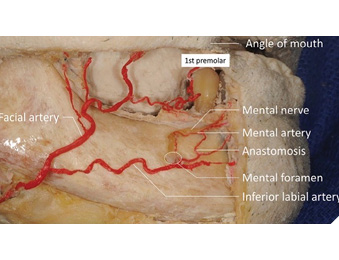

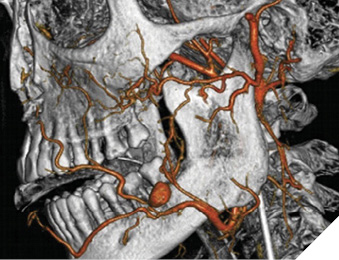

The facial artery arises from the anterior aspect of the ECA travels in the submandibular region and emerges on the face at the antegonial notch in close proximity to the third molar region (Fig. 7).10 The facial artery gives off several branches (ascending palatine artery, tonsillar artery, submental artery, inferior masseteric artery, jugal trunk, middle mental artery, anterior jugal artery) before terminating as the superior labial artery, inferior labial artery, lateral nasal artery and angular artery at the medial aspect of the orbit.11 The submental artery arising from the facial artery anastomoses with the sublingual artery and the mylohyoid artery of the inferior alveolar artery.4

Fig. 7

Bleeding complications can occur intra-operatively, or they can have a delayed post-operative presentation. Vascular injuries can be divided into four categories based on the type of vessel involved and the degree of damage, as listed below:

- Arterial bleeding

- Venous bleeding

- Capillary and/or small vessel/bone marrow bleeding

- Hematoma formation/delayed bleeding

Arterial injuries often result in pulsatile brisk bleeding from the lingual, inferior alveolar or facial artery. Venous hemorrhage present as a continuous ooze which can be challenging to manage. Osseous bleeding can present similar to arterial injury, most commonly from the marrow spaces of the mandible. Bleeding can dissect soft tissue fascial planes similar to odontogenic infections, which can lead to airway compromise if uncontrolled. Pseudoaneurysms are a delayed complication where vessel wall injury leads to a weakened, blood-filled cavity prone to rupture and severe hemorrhage days to weeks after the initial surgery. There have been reports of pseudoaneurysm formation of the facial artery following third molar removal (Fig. 8).12,13

Fig. 8

Hemorrhage prevention and management

Hemorrhage prevention is best achieved pre-operatively during the initial consultation. It is important to systematically obtain a comprehensive past medical and surgical history. In the context of bleeding prevention, coagulopathies (i.e., hemophilia, von Willebrand disease), liver disease and hypertension as well as the use of anticoagulants or antiplatelet therapy (i.e., warfarin, clopidogrel) should be determined. Gathering information regarding prior surgeries, dental extractions or significant bleeding episodes is also prudent. A detailed clinical exam should be conducted. Oral manifestations of coagulopathies such as mucosal petechiae, spontaneous gingival bleeding and gingival jaundice may be identified (Fig. 9).14 Once all clinical information has been obtained, decisions regarding case selection are undertaken. Appropriate case selection is the single most important factor in the prevention of significant hemorrhage and unnecessary patient morbidity.

Fig. 9

There are several intra-operative techniques to manage hemorrhage prior to emergency activation and potential transfusion. Immediate hemostasis can be achieved with direct gauze pressure or bimanual palpation in the anterior FOM. Appropriate lighting and visualization with adequate suction is crucial to visualize the source of bleeding. Local hemostatic agents that can be applied include TXA, chemical cautery (i.e., silver nitrate), bone wax, oxidized regenerated cellulose (i.e., SURGICEL®), gelatin sponges (i.e., Gelfoam®), collagen (i.e., AviteneTM, CollaPlug), topical thrombin (i.e., SURGIFLO®, FLOSEAL®) and topical fibrin (i.e., TISSEEL®). Direct vessel ligation is performed if possible. Due to the acidity and potential for nerve injury, oxidized regenerated cellulose should not be placed in close proximity to nerves. Bone wax is generally effective for osseous bleeding from medullary spaces. If these measures fail, monopolar or bipolar electrocautery may be utilized.

In the emergency or hospital setting, there are several hemorrhage management strategies that aim to treat the patient medically and surgically. The approach to any deteriorating or emergency patient should always begin with assessment of the A,B,C’s (airway, breathing and circulation).

Profuse bleeding, particularly if there is hematoma formation around the patient’s airway has the potential to lead to airway compromise. Signs of a compromised airway may be difficult to recognize in the early stages, and there is a potential for rapid deterioration. As such, situational awareness and being prepared to manage further deterioration may help save a patient’s life. Early stages of airway compromise may have no obvious signs or may present with only subtle voice changes or hoarseness. Later, this may progress to dyspnea, agitation, and eventual stridor. Stridor generally indicates that the extra-thoracic airway has narrowed to a diameter of less than 4 mm. In the event of airway compromise, it is important to determine if it is a non-critical situation (patient is stable enough to be transferred to a hospital or operating room) or critical airway compromise (immediate intervention is required). Immediate intervention may include evacuation of a hematoma, use of an advanced airway device, or obtaining a surgical airway, such as a cricothyrotomy or tracheostomy.

It is critical to obtain a prompt physical examination often with laboratory investigations. If the patient is adequately stabilized, advanced imaging in the form of a CT scan may also be obtained to help visualize a hematoma. The patient is also assessed for hemodynamic stability (HR, BP, MAP, SpO2) to direct immediate care. If there is active exsanguinating hemorrhage and hemodynamic instability with signs of hypovolemic shock (hypotension, tachycardia, altered mental status, cool and clammy), a massive transfusion protocol (MTP) may be initiated. The primary aim of a MTP is to prevent the “lethal triad” of hypothermia, acidosis and coagulopathy. During an MTP, pRBCs, fresh frozen plasma and platelets are administered in a 1:1:1 ratio, often with IV TXA, fibrinogen and calcium. Stat CBC and electrolytes are ordered to determine Hb, hematocrit and platelet levels as well as electrolyte derangements. Arterial blood gases are drawn to assess for acidosis. It is important to also obtain stat coagulation studies, including prothrombin time (PT), activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), international normalized ratio (INR) and fibrinogen levels. While the patient is undergoing resuscitation, the source of the bleeding is definitively managed either surgically whereby the patient is transported emergently to the operating room or by interventional radiology via embolization.

If bleeding is encountered in a dental office by a practitioner who is not equipped to adequately manage the bleeding, the following steps should be followed:

- Apply direct pressure to the area. Don’t panic!

- Call for help. In the event of significant bleeding that does not stop with pressure, this may involve activating EMS.

- If the patient is being transferred to another facility and is actively bleeding, they need to be accompanied by the most-capable person for managing the bleed. In a dental office, this will likely be the dentist. In the event of significant hemorrhage, the nearest ED should be notified while the patient is being transferred so they can be as prepared as possible.

Conclusion

Life-threatening hemorrhage is a significant complication that clinicians performing oral surgical procedures may encounter and subsequently manage. A thorough understanding of the regional anatomy in the maxillofacial complex is crucial to avoid inadvertent damage to surrounding structures. Systematic pre-operative consultations and appropriate case selection are the most effective strategies for prevention of significant hemorrhage and unnecessary patient morbidity. Practicing sound surgical techniques enables the clinician to prevent, recognize, and manage significant bleeding. In the event of uncontrollable hemorrhage or airway compromise, an understanding of advanced medical and surgical management strategies is critical to prevent adverse patient outcomes.

Oral Health welcomes this original article.

References

- Cheng, S. Y., Lin, T. Y. & Yang, C. J. Respiratory Distress After Wisdom Tooth Extraction. Journal of Emergency Medicine 65, e144–e145 (2023).

- Moghadam, H. & Caminiti, M. Case Report Life-Threatening Hemorrhage after Extraction of Third Molars: Case Report and Management Protocol. J Can Dent Assoc (Tor) 68, 670–674 (2002).

- Lieberman, B. L. et al. Control of life-threatening head and neck hemorrhage after dental extractions: A case report. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 68, 2311–2319 (2010).

- Carreira-Nestares, B., Urquiza-Fornovi, I., Carreira-Delgado, M. C., Gutierrez-Díaz, R. & Sánchez-Aniceto, G. Clinical Case and Literature Review of a Potentially Life-Threatening Complication Derived from Mouth Floor Hematoma after Implant Surgery. European Dental Research and Biomaterials Journal (2024) doi:10.1055/s-0043-1776284.

- Peñarrocha-Diago, M. et al. Floor of the mouth hemorrhage subsequent to dental implant placement in the anterior mandible. Clin Cosmet Investig Dent 11, 235–242 (2019).

- Law, C., Alam, P. & Borumandi, F. Floor-of-Mouth Hematoma Following Dental Implant Placement: Literature Review and Case Presentation. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery vol. 75 2340–2346 Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2017.07.152 (2017).

- Vehmeijer, M. J. J. B., Verstoep, N., Wolff, J. E. H., Schulten, E. A. J. M. & van den Berg, B. Airway Management of a Patient with an Acute Floor of the Mouth Hematoma after Dental Implant Surgery in the Lower Jaw. Journal of Emergency Medicine 51, 721–724 (2016).

- Bui, C. H., Seldin, E. B. & Dodson, T. B. Types, Frequencies, and Risk Factors for Complications after Third Molar Extraction. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 61, 1379–1389 (2003).

- Bagheri, S. C., Khan, H. A. & Stevens, M. R. Complex Dental Implant Complications. (Springer, 2020).

- Iwanaga, J., Shiromoto, K. & Tubbs, R. S. Releasing incisions of the buccal periosteum adjacent to the lower molar teeth can injure the facial artery: an anatomical study. Surgical and Radiologic Anatomy 42, 31–34 (2020).

- Harrigan, M. R. & Deveikis, J. P. Handbook of Cerebrovascular Disease and Neurointerventional Technique. (Humana Press, 2023).

- Marco de Lucas, E. et al. Life-threatening pseudoaneurysm of the facial artery after dental extraction: successful treatment with emergent endovascular embolization. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology and Endodontology 106, 129–132 (2008).

- Pukenas, B. A., Albuquerque, F. C., Pukenas, M. J., Hurst, R. & Stiefel, M. F. Novel endovascular treatment of enlarging facial artery pseudoaneurysm resulting from molar extraction: A case report. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 70, (2012).

- Napeñas, J. J., Brennan, M. T. & Elad, S. Oral Manifestations of Systemic Diseases. Dermatol Clin 38, 495–505 (2020).

About the authors

Dr. Andrew Lombardi is a PGY-3 Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery resident at the University of Toronto.

Dr. Eddie Reinish is a staff Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeon affiliated with the University of Toronto practicing at Humber River Health in Toronto, Ontario.

Dr. Wendall Mascarenhas is a staff Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeon affiliated with the University of Toronto practicing at Mount Sinai Hospital in Toronto, Ontario.

Dr. Justin Kierce is an Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeon practicing in Kelowna, British Columbia.