This research paper explores the effectiveness of Motivational Interviewing (MI) in addressing and assisting participants in overcoming nail-biting habits. The study aimed to understand how MI could be used as a behavioural intervention to support individuals in making positive changes regarding this common yet challenging habit.

The outcomes of the study were notably positive. Motivational Interviewing provided a structured yet flexible approach that empowered participants to explore their motivations for change, recognize the discrepancies between their current behaviours and desired outcomes, and build confidence in their ability to stop nail-biting. Through techniques such as the ‘importance ruler’ and ‘developing discrepancy,’ participants were able to gain insight into their habits and identify personal reasons for change. This process not only enhanced their commitment to stopping nail-biting but also fostered a sense of autonomy and self-efficacy.

Over the course of the research, participants reported a significant reduction in their nail-biting behaviour. The support provided through daily motivational quotes, reflective listening, and personalized goal setting played a crucial role in maintaining their progress.

By the conclusion of the study, all participants had made noticeable improvements, with many expressing increased confidence in their ability to maintain these changes long-term.

In summary, the use of Motivational Interviewing in this context proved to be an effective method for promoting behaviour change. The positive outcomes suggest that MI could be a valuable tool for dental professionals and other healthcare providers in supporting patients who struggle with nail-biting or similar habits.

Introduction and behaviour change question

Nail-biting, also known as onychophagia, is a chronic, repetitive, and compulsive condition commonly observed in children and young adults, which can persist into adulthood. The current literature estimates the prevalence of nail-biting at 20% to 30% of the general population.1

Factors contributing to nail-biting include genetic predispositions and underlying psychiatric conditions; however, there is a paucity of studies examining the distribution and determinants of this condition.2

This habit is often associated with anxiety, stress, frustration, boredom, and other emotional factors. Onychophagia can result in oral health issues such as malocclusion, enamel wear, gingival injuries, and oral infections, as well as skin infections around the nails and fingertips. Prevention and treatment of nail-biting require a multidisciplinary approach, potentially involving psychosocial, psychiatric, dermatologic, and dental interventions.2

Chronic nail-biters have a higher incidence of Enterobacteriaceae in their oral cavities.3 These bacteria are transient pathogens and can significantly influence the oral microbiome, which plays a role in systemic diseases and conditions.4

With their approval to share, I chose this topic because my daughter, son, future daughter-in-law, and I are all nail-biters. Getting acrylic nails has helped me stop biting my nails, especially now that I’m not working in a clinical setting.

I am passionate about addressing this oral health problem and aim to bring more attention to it through my research. I struggled to find comprehensive articles on nail biting in dental journals and forums, highlighting the need for more awareness and information on this disorder. By exploring this topic to address this question, “What are the outcomes of using Motivational Interviewing (MI) to address and assist in overcoming nail-biting habits in participants?”, I hope to help my participants break the habit.

Current knowledge

Nail-biting is a common yet challenging problem that is often overlooked in the dental community. Despite its prevalence, it is not a behaviour that can be easily stopped and frequently goes unnoticed during dental assessments. Nail-biting not only affects the oral cavity, leading to dental issues such as enamel damage, gingival trauma and possible infection, but it also impacts the overall health of patients. It can influence their emotional well-being, social interactions, and psychological state, making it a multifaceted issue that requires a comprehensive approach to address effectively.5

Onychophagia is commonly referred to as nail biting and is a chronic condition that is repetitive and compulsive in nature and generally seen in children and young adults.2 Onychophagia is a Greek word, onycho means fingernail or toenail and phagia is to eat or consume.5

Oral habits usually develop during infancy and have natural starting and ending points. Common oral behaviours include thumb sucking, nail biting, lip biting, and mouth breathing. Habits are behaviours that are carried out automatically and consistently. Parents use pacifiers to soothe infants and toddlers. Oral habits can stay the same throughout childhood or alter over time to cope with different emotional pressures, such as thumb sucking or nail biting.1

Nail biting is one of the most common oral habits. It typically starts at the age of three or four years and can last throughout adolescence.1 If it is ignored and not treated properly in childhood, it often continues into adulthood. It occurs in 20 to 33% of children and 45% in teenage groups. By the age of 18 years, the frequency of nail-biting decreases; however, it may persist in some adults.5 One study notes a 37% prevalence among individuals aged 3 to 21 years. Nail biting remains prevalent among young adults, with one study reporting a 21.5% prevalence among those age 18 to 35 years.2

Potential risk factors include an extended period of bottle feeding, and pacifier use.2 Psychiatric disorders and other stereotypic behaviours are present in more than 80% of clinical samples of children with nail-biting and many of their parents had psychiatric illnesses, primarily sadness.1 Nail-biting is an oral habit often used to relieve stress. This behaviour typically occurs when the individual is experiencing stress, frustration, nervousness, embarrassment, hunger, or boredom. Those who engage in nail-biting often feel powerless, ashamed, and depressed as a result. Onychophagia is classified as a behaviour within the obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorder. It can also be considered as a self-mutilative automatic behaviour. This self-grooming action can cause physical injury and lead to mental health issues such as significant emotional distress, anxiety, and depression. Nail-biting often begins as a response to anxiety, severe stress or tension, and can evolve into a habit that persists even after the initial stress or anxiety has subsided. If not addressed and treated properly during childhood, it is likely to continue into adulthood.5

People engaging in nail-biting might have certain personality traits which may be referred to as signs of a perfectionist personality. Research suggests that boredom and frustration are two traits that come to the surface quickly with a perfectionist personality. In the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fifth Edition (DSM–5), nail-biting is classified as another specified obsessive-compulsive and related disorder with specification of body-focused repetitive behaviour (BFRBs); whereas, the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems ICD-10 classifies the practice as other specified behavioural and emotional disorders with onset usually occurring in childhood and adolescence.5

Nail-biters can also be called pathological groomers. One study claimed that nail-biting is considered an involuntary behaviour with close to 70% of people reporting tension before the behaviour and 40% reporting a feeling of temporary pleasure after the nail had been bitten. Many nail-biters feel depersonalization during the episode.5

There are various classifications of nail-biting, including those who bite without realizing it, those who bite to manage anxiety, and those who do so for attention. Some individuals bite their nails to control aggression through self-injurious gestures. As mentioned, nail-biting can also be part of the obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) spectrum and can be classified as either pathological or non-pathological.5

Nail-biting is often overlooked due to its benign nature; however, if left untreated it can cause many complications. It is poorly misunderstood, misdiagnosed, and is an untreated disorder with very little published articles found; however, it has been receiving growing scientific attention.5

Nail-biting can not only lead to dental complications, such as enamel damage and gingival trauma, but also to other physical complications, including malformed nails, infection of the nail and surrounding soft tissue, an increased risk of parasitic and stomach infections due to swallowing nail particles and dirt, Temporomandibular Joint pain, injury to the gingiva, paronychia, self-inflicted gingival injuries, secondary bacterial infections, and osteomyelitis.5

There have been studies indicating that Enterobacteriaceae can be introduced into the oral cavity with nail-biting. Nail-biting increases the carriage of several opportunistic environmental microorganisms into the oral cavity which can cause a variety of infections. These include Enterobacteriaceae, which is a group of facultative anaerobic gram-negative bacteria that are thought to be transient or non-resident members of the oral cavity in healthy individuals. Some potentially pathogenic intestinal microorganisms of the Enterobacteriaceae family like Escherichia Coli (E. coli) and Enterobacter have been noted in the oral cavity of nail biters. Enterobacteriaceae were positive for 72% of the children studied. Of them, the nail-biting or orthodontic treatment group comprised 89%. E. coli was positive in 38% of the children. Those with a combination of nail-biting and undergoing orthodontic treatment exhibited highest colony forming units (CFU/ml) and those without nail-biting or orthodontic treatment exhibited the lowest.4

Enterobacteriaceae can cause a variety of infections in humans, ranging from gastrointestinal diseases, urinary tract infections, respiratory infections, and sepsis. They are significant in both clinical and public health settings due to their role in antibiotic resistance and hospital-acquired infections. Dental professionals are usually interested in dental and gingival problems as a result of chronic nail-biting; however, the habit of nail-biting can result in autoinoculation of pathogens and transmission of infection to distant body parts. For children with inadequate and poor toilet hygiene, enteric bacteria can pose a potential threat and danger by penetrating the body via mouth as a result of nail-biting, and can lead to various infections.3

There are various methods to assist prevention of nail-biting. Behavioural Therapy is the first line gold standard treatment. In Behavioural Therapy, various techniques can be used such as Motivational Interviewing. Stress reduction techniques such as yoga, mindfulness meditation, and breathing exercises can help address the underlying anxiety and tension that often trigger nail-biting. Keeping the hands and mouth occupied with alternative activities (Habit Replacement Therapy), like using stress balls, fidget spinners, or chewing gum, can also be effective. Additionally, behavioural strategies like habit reversal training, applying bitter-tasting nail polish, keeping nails well-trimmed, and setting small, achievable goals can provide further support. Regular monitoring and encouragement from a dental professional can enhance the success of these interventions, helping individuals to overcome this habit and improve their overall oral health.5

Nail-biting is a complex disorder that, if left untreated, can lead to serious consequences. Chronic nail-biting often goes unrecognized, underdiagnosed, and undertreated. Dental hygienists are the first line of defense in identifying and screening for potential nail-biting disorders. We play a crucial role in enhancing the quality of life for our patients. Understanding the nature of nail-biting, its impact on our patients, and how to effectively screen for this behaviour is within our scope of practice. Additionally, recognizing when to refer patients for further support is essential in providing comprehensive care.

I conducted a survey among a group of dental hygienists to provide a clear overview of the current practices, challenges, and potential improvements related to nail-biting assessments in dental hygiene. A total of 628 participants responded to the survey, with 97% identifying as dental hygienists. Of these, 99% were Canadian, and 85% had been practicing for more than 10 years. The majority, 70%, worked in a general practice setting, while 8% are dental hygiene practice owners.

The research reveals varied practices among dental hygienists regarding the assessment of patients for nail-biting. Only a small fraction, 9%, always conducts such assessments, while 14% often do, 26% sometimes, 28% rarely, and 22% never consider this habit during patient evaluations. Triggers for assessing nail-biting typically include visual indicators such as chipping and incisal wear, alongside outcomes from myofunctional assessments. Timing for these assessments varies when they are conducted, with 33% occurring during a New Patient Exam and 28% at the Re-care appointment. Methods employed primarily include visual examination by 48% of respondents, while 18% utilize questionnaires.

Regarding the receptiveness to discussing nail-biting with patients, the data from 418 respondents indicated that 11% were very receptive, 35% somewhat receptive, 22% neutral, 8% somewhat unreceptive, and 4% very unreceptive. Ninety-five percent of participants reported receiving no training on how to assess and address nail-biting, highlighting a significant gap in professional preparation. Suggestions for improvement included the incorporation of a habit section under risk factors in assessments, collaboration with occupational health providers or psychologists, more frequent review of habits, and the development of a simple questionnaire for dental hygienists to use with patients.

The survey revealed that most dental hygienists are not trained to assess or address nail-biting. However, there is clear recognition of the need for such training and resources. The survey itself has prompted many respondents to consider adding nail-biting assessments to their practice, bringing this issue to the forefront of their attention. Respondents strongly recommended the development of a course or educational materials to help dental hygienists integrate nail-biting assessments into their routine and better support their patients.6

Behaviour change techniques/models which were implemented and tested

Behavioural Therapy formed the foundation of my research, where I implemented techniques such as Motivational Interviewing (MI) and Habit Replacement Therapy (HRT).

In this study, a variety of data collection methods were employed to comprehensively assess the knowledge and practices of dental hygienists regarding nail-biting. Surveys were distributed to gauge whether nail-biting habits are routinely included in assessments. To gather baseline data and monitor changes over time, questionnaires were administered to the participants to gauge their motivation for quitting nail-biting and to understand their values (Appendix C). To track progress, interviews employing motivational interviewing (MI) techniques were conducted at three critical stages: the initial phase, midway, and at the study’s conclusion (Appendix F). Observational methods included examining the condition of participants’ nails at both the start and end of the research period. Participants also contributed to data collection by taking images of their nails (Appendix G). Diaries and self-reports were maintained to provide daily and weekly reflections on their habits. The ‘Nail-Biting Scale’ was completed weekly for a more formal behavioral assessment to quantify the severity and frequency of nail-biting (Appendix D). Additionally, I created a support group, where I sent daily motivational quotes (Appendix E).

In the MI sessions, I used open-ended questions and employed the ‘importance ruler’ to initiate discussions. I also applied the ‘develop discrepancy’ technique to help participants recognize the gap between their current behavior and their goals, along with ‘reflective listening’ to ensure participants felt heard and understood.7 (Appendix H).

Experimental methods included the implementation of habit replacement interventions, further enriching the study’s findings. To foster collaboration and autonomy, I offered participants various tools to try. In the first week, each participant chose a Stimmie—a modernized rubber tip stimulator that fits conveniently in a pocket. This Stimmie was well-received and effective, prompting me to provide additional units in week two for greater convenience. As a motivational boost, I surprised participants with a manicure set and cuticle oil. These were well-received, and participants reported enjoying maintaining their nails, which supported their efforts to reduce nail-biting.

New knowledge

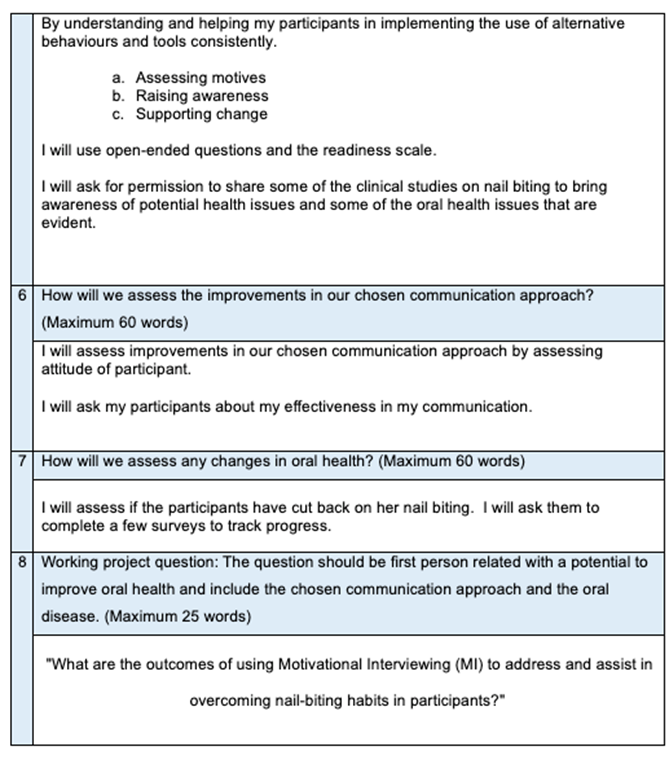

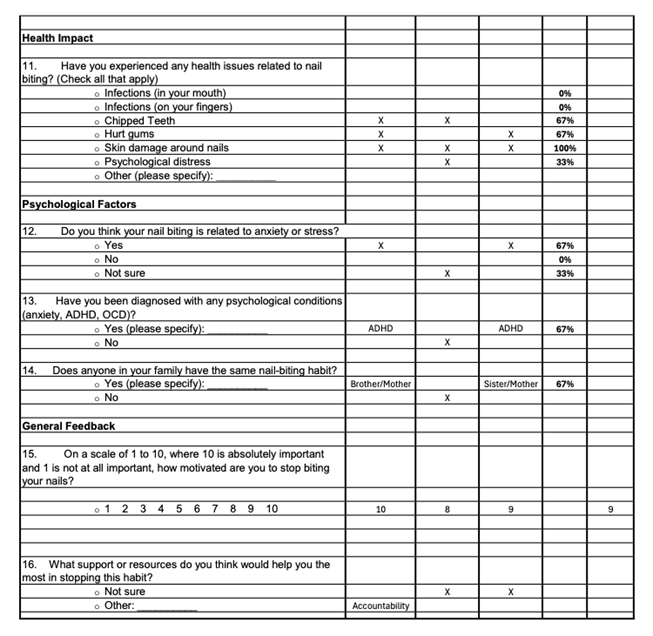

The initial questionnaire revealed that all participants had been biting their nails for over 10 years and expressed a strong desire to stop. A significant 67% of participants reported feeling guilt associated with their nail-biting habit. Participants were largely aware of their triggers, with 67% identifying stress and 100% pointing to anxiety, boredom, and habit as key factors. Although they had attempted various strategies to stop—such as using bitter nail polish (33%), keeping nails trimmed (67%), keeping nails polished (67%), and using fidget tools (33%)—none of these methods had proven to be more than slightly successful or sustainable long-term. Despite their efforts, the participants reported experiencing direct health impacts from nail-biting, including chipped teeth (67%), hurt gingiva (67%), and skin damage around their nails (100%). Additionally, 33% of participants experienced psychological distress related to the habit. Notably, 67% of participants felt their nail-biting was related to anxiety or stress, and the same percentage had been diagnosed with ADHD. Furthermore, 67% reported having other family members who also bite their nails. On a scale of 1-10, the participants had an average motivation score of 9 for stopping their nail-biting habit.

Nail-biting has been a long-term issue for these participants, who are aware of the physical and psychological damage it causes. While they are highly motivated to stop, they have not found an effective long-term strategy to break the habit. A targeted strategy is needed to help this motivated group overcome this persistent and personally destructive behaviour.

During the Motivational Interviewing sessions, I utilized the ‘importance ruler’ to initiate each discussion. Two of the participants scored a 10 for importance, indicating strong motivation to change, while the third participant initially scored lower due to ambivalence. This presented a valuable opportunity to explore their uncertainties and support them in realizing that the power to change lies within themselves. By the third interview, this participant also scored a 10, demonstrating a significant shift in their readiness to change.

The technique of ‘developing discrepancy’ was integral to helping participants recognize the gap between their current behavior and their goals. By highlighting the contrast between their values and their nail-biting habit, participants were able to see the need for change more clearly. This process not only fueled their motivation but also built their confidence in taking actionable steps toward breaking the habit.

Throughout the MI sessions, I found it incredibly empowering to witness participants’ growing awareness of how nail-biting affected their lives and their determination to overcome it. During the second and final interviews, all participants expressed how much the daily motivational quotes had supported them. Participating in the research brought their habit to the forefront, serving as a constant reminder that they had the power to change.

In terms of HRT, participants’ motivation combined with the practical tools provided, such as the manicure set and Stimmie, contributed to the success of the intervention. They took pride in maintaining their nails, which further reinforced their commitment to breaking the habit.

This research process has been transformative for me as well. Initially, I worried that the daily motivational quotes might be seen as redundant, but hearing participants express how much they valued these reminders was a powerful moment. Witnessing the real-world impact of concepts I have studied during my Bachelor’s Degree, such as ‘Make Every Contact Count,’ has deepened my understanding of how guided conversations can drive positive behavioural change.

I have also evolved in my approach, particularly in using open-ended questions and reflective listening. These techniques have not only enhanced my interactions with participants but have also influenced how I engage with others in my professional and personal life.

Discussion

Since writing the research proposal, I’ve experienced significant personal and professional growth. My confidence in conducting research has increased, and my thinking has expanded, allowing me to approach behavioural change with a more open mind. I have become a better listener, incorporating reflective practices to improve my connections with others. My participants have also shared that my communication was effective. This journey has shown me that even small steps in behaviour change can have a big impact. My organizational skills, particularly in time management, have also improved, helping me focus efficiently while avoiding burnout. Overall, I feel more equipped to support others in achieving meaningful change.

Since my participants are making progress in reducing their nail-biting habits, I plan to stay connected with them to provide ongoing support and track their progress. This will help reinforce their behaviour changes and sustain long-term success.

Building on this research, I am considering developing a nail-biting habit app for dental professionals, featuring behaviour tracking, motivational prompts, and educational resources. Additionally, I plan to create a course on onychophagia to share these insights.

This research has influenced my approach to patient care, particularly in using open-ended questions and reflective listening, which have been effective in my interactions. By sharing these insights with colleagues, we can collectively enhance our ability to support patients in making positive behaviour changes.

Appendices

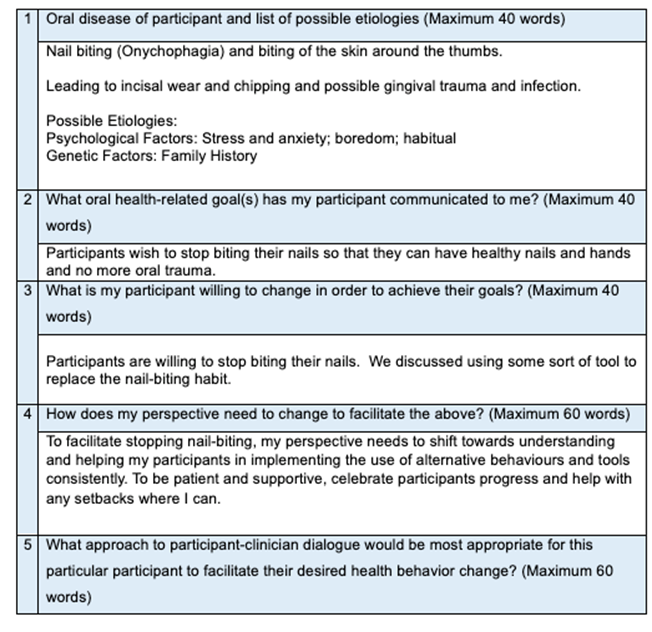

Appendix A: Proposal

Class 3A-24

Proposal Worksheet for health behaviour change project

Name of Student: Kathleen Bokrossy

Appendix B: Sample Ethics Statement and Consent Form

Dear -----,

This year, I,--------, am studying with O’Hehir University to earn a Bachelor of Science degree in Oral Health Promotion. An important part of my studies is completing a project which will help my patients to improve their oral health through a new approach, called health behavioral change. I would be most appreciative if you would choose to participate.

My data collection methods will include:

• Surveys and Questionnaires

• Interviews

• Observations

• Diaries and Self-Reports

• Behavioral Assessments (Nail Biting Scale)

• Experimental Methods (ie fidget ring, pen, bitter tasting nail polish)

I guarantee confidentiality of information and promise that no names will be made public. Participation is simple and easy.

If you choose not to participate you are free to do so with no consequences. If you choose to participate and wish to be kept informed about the progress of the project, I can keep you informed via email or telephone. If you consent, please sign your permission below at your earliest convenience.

I, (print name, and sign here) ________________________________________-______________________consent to participate in the project described above. I understand that at any time I may withdraw my consent.

Please include your contact information if you want to be updated during the project.

Appendix C: Questionnaire for Participants and Results

Nail Biting Research Questionnaire

Participant Information

1. Age: __________

2. Gender: __________

3. Occupation/Student Status: __________

Nail Biting Behavior

4. How frequently do you bite your nails?

o Never

o Rarely (a few times a month)

o Occasionally (a few times a week)

o Frequently (daily)

o Constantly (multiple times a day)

5. How long have you been biting your nails?

o Less than 1 year

o 1-3 years

o 3-5 years

o 5-10 years

o More than 10 years

6. What triggers your nail-biting behavior? (Check all that apply)

o Stress

o Anxiety

o Boredom

o Concentration

o Habit

o Other (please specify): __________

7. How do you feel after biting your nails?

o Satisfied

o Guilty

o Indifferent

o Other (please specify): __________

8. Have you ever tried to stop biting your nails?

o Yes

o No

Attempts to Stop

9. If yes, what methods have you tried? (Check all that apply)

o Bitter-tasting nail polish

o Wearing gloves

o Keeping nails trimmed

o Keeping nails polished

o Fidget tools (e.g., fidget ring, stress ball)

o Behavioral therapy

o Motivational Interviewing

o Other (please specify): __________

10. How successful were these methods?

o Very successful

o Moderately successful

o Slightly successful

o Not successful

Health Impact

11. Have you experienced any health issues related to nail biting? (Check all that apply)

o Infections (in your mouth)

o Infections (on your fingers)

o Chipped Teeth

o Hurt gums

o Skin damage around nails

o Psychological distress

o Other (please specify): __________

Psychological Factors

12. Do you think your nail biting is related to anxiety or stress?

o Yes

o No

o Not sure

13. Have you been diagnosed with any psychological conditions (anxiety, ADHD, OCD)?

o Yes (please specify): __________

o No

14. Does anyone in your family have the same nail-biting habit?

o Yes (please specify): __________

o No

General Feedback

15. On a scale of 1 to 10, where 10 is absolutely important and 1 is not at all important, how motivated are you to stop biting your nails?

o 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

16. What support or resources do you think would help you the most in stopping this habit?

o Not sure

o Other: __________

Thank you for participating in this study. Your responses will be used as a baseline in my Action Research Project.

Nail-Biting Questionnaire Results

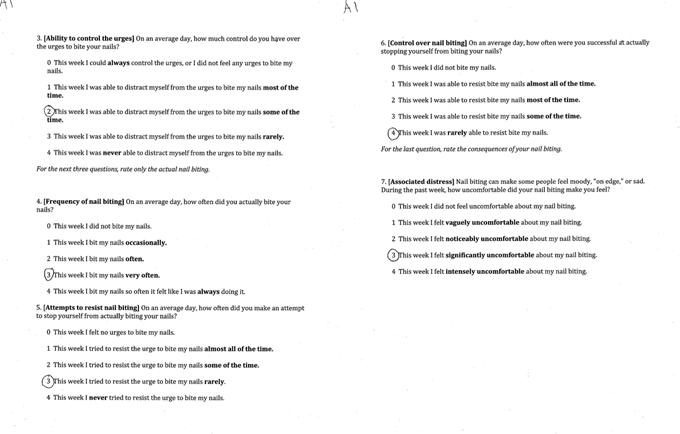

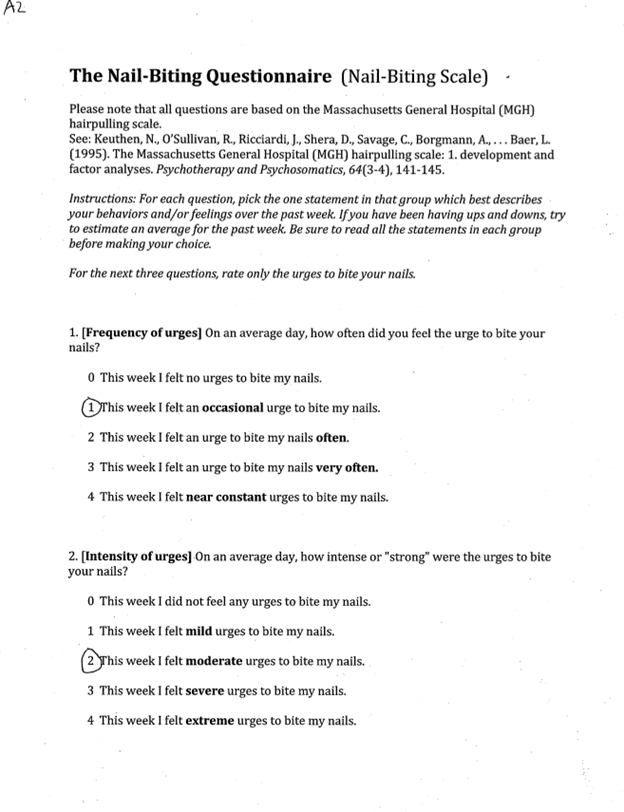

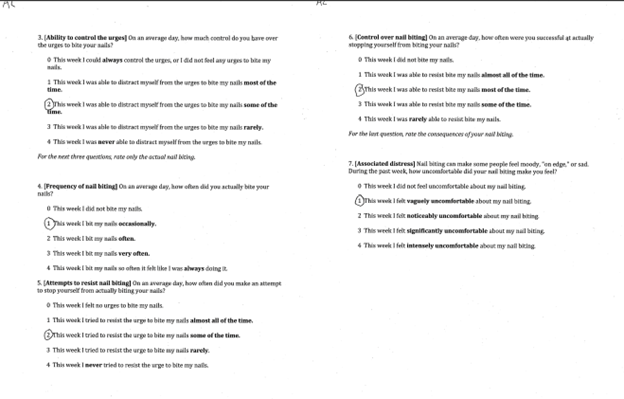

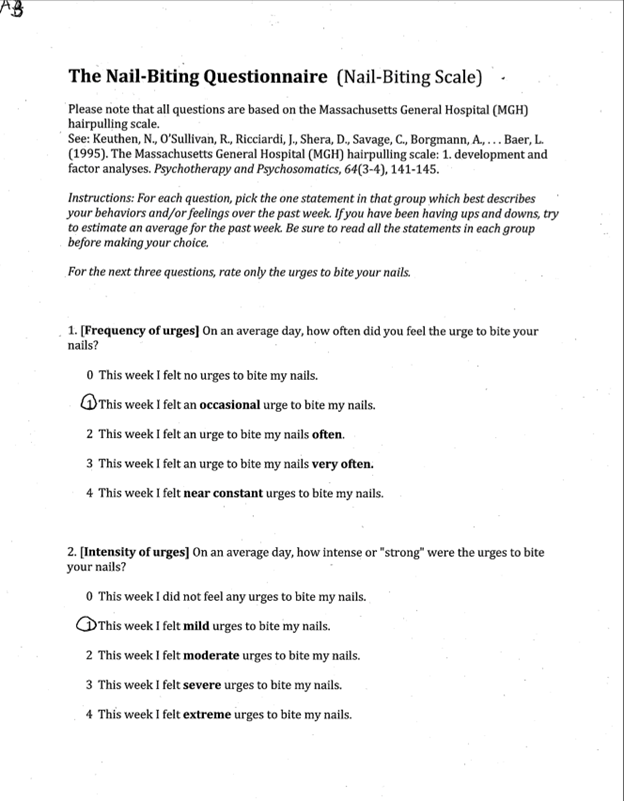

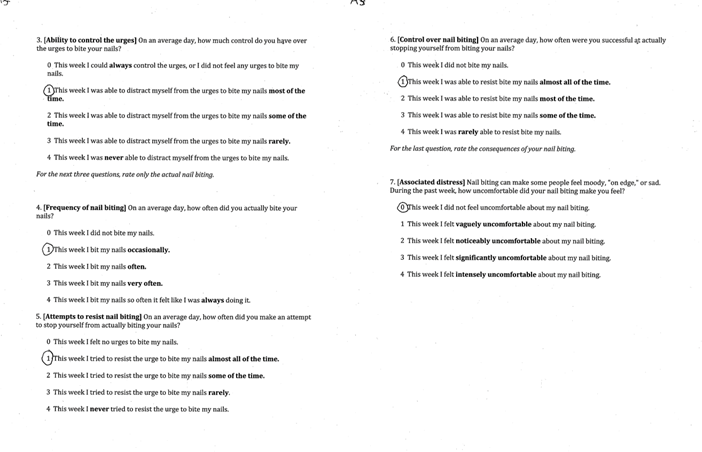

Appendix D: Nail-Biting Scale

Please note that all questions are based on the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) hairpulling scale.

See: Keuthen, N., O’Sullivan, R., Ricciardi, J., Shera, D., Savage, C., Borgmann, A., . . . Baer, L. (1995). The Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) hairpulling scale: 1. development and factor analyses. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 64(3-4), 141-145.

Instructions: For each question, pick the one statement in that group which best describes your behaviors and/or feelings over the past week. If you have been having ups and downs, try to estimate an average for the past week. Be sure to read all the statements in each group before making your choice.

For the next three questions, rate only the urges to bite your nails.

1. [Frequency of urges] On an average day, how often did you feel the urge to bite your nails?

0 This week I felt no urges to bite my nails.

1 This week I felt an occasional urge to bite my nails.

2 This week I felt an urge to bite my nails often.

3 This week I felt an urge to bite my nails very often.

4 This week I felt near constant urges to bite my nails.

2. [Intensity of urges] On an average day, how intense or "strong" were the urges to bite your nails?

0 This week I did not feel any urges to bite my nails.

1 This week I felt mild urges to bite my nails.

2 This week I felt moderate urges to bite my nails.

3 This week I felt severe urges to bite my nails.

4 This week I felt extreme urges to bite my nails.

3. [Ability to control the urges] On an average day, how much control do you have over the urges to bite your nails?

0 This week I could always control the urges, or I did not feel any urges to bite my nails.

1 This week I was able to distract myself from the urges to bite my nails most of the time.

2 This week I was able to distract myself from the urges to bite my nails some of the time.

3 This week I was able to distract myself from the urges to bite my nails rarely.

4 This week I was never able to distract myself from the urges to bite my nails.

For the next three questions, rate only the actual nail biting.

4. [Frequency of nail biting] On an average day, how often did you actually bite your nails?

0 This week I did not bite my nails.

1 This week I bit my nails occasionally.

2 This week I bit my nails often.

3 This week I bit my nails very often.

4 This week I bit my nails so often it felt like I was always doing it.

5. [Attempts to resist nail biting] On an average day, how often did you make an attempt to stop yourself from actually biting your nails?

0 This week I felt no urges to bite my nails.

1 This week I tried to resist the urge to bite my nails almost all of the time.

2 This week I tried to resist the urge to bite my nails some of the time.

3 This week I tried to resist the urge to bite my nails rarely.

4 This week I never tried to resist the urge to bite my nails.

6. [Control over nail biting] On an average day, how often were you successful at actually stopping yourself from biting your nails?

0 This week I did not bite my nails.

1 This week I was able to resist bite my nails almost all of the time.

2 This week I was able to resist bite my nails most of the time.

3 This week I was able to resist bite my nails some of the time.

4 This week I was rarely able to resist bite my nails.

For the last question, rate the consequences of your nail biting.

7. [Associated distress] Nail biting can make some people feel moody, "on edge," or sad. During the past week, how uncomfortable did your nail biting make you feel?

0 This week I did not feel uncomfortable about my nail biting.

1 This week I felt vaguely uncomfortable about my nail biting.

2 This week I felt noticeably uncomfortable about my nail biting.

3 This week I felt significantly uncomfortable about my nail biting.

4 This week I felt intensely uncomfortable about my nail biting.

Sample of The Nail-Biting Questionnaire Results from a Participant: 1st Week

Mid-way

Final Week

Appendix E: Daily Motivational Quotes

Each small step you take away from nail biting is a giant leap towards better health. Keep going, you’re stronger than the habit!

Every time you resist the urge to bite your nails, you’re building a new, healthier habit. Celebrate your progress!

Remember, the power to change is within you. Stay mindful and focused—one day at a time, one moment at a time.

You’ve got this! Picture the healthy, beautiful nails you’re working towards and let that vision motivate you.

Breaking a habit isn’t easy, but with each day, you’re proving your strength and determination. Keep pushing forward!

Stay positive and patient with yourself. Each time you choose not to bite your nails, you’re closer to your goal.

Your journey to stop nail biting is a testament to your resilience. Keep reminding yourself why you started.

Take pride in your progress, no matter how small. Each success is a victory worth celebrating!

Stay focused on your goal—healthy, strong nails. Every effort counts and brings you closer to success.

You are capable of amazing things. Believe in your ability to overcome this habit and reclaim control.

Appendix F: Motivational Interviewing Sample Questions

1st Call

Open-ended questions:

• On a scale of 1 to 10, how important is it for you to stop biting your nails right now?

• I would like to understand a little more about your nail-biting habit? How often do you find yourself doing it?

Possible response:

• I see, you're saying that you often bite your nails when you're stressed or anxious. That sounds challenging. It's completely understandable to turn to habits like nail biting when you're feeling stressed. Many people experience similar challenges.

• What situations or feelings usually trigger your nail biting? Can you tell me more about when you first noticed this habit? Have you observed any particular situations or feelings that make it worse?

• Have you noticed any changes in your nails or dental health that you think might be related to your nail biting? What impact, if any, do you think nail biting has on your oral health?

Possible response:

• Nail-biting can impact your health, potentionally causing issues like chipped teeth or gum infections. It’s important to address both the habit and its effects on your dental and overall health.

• How do you feel after you bite your nails? Does it help you manage stress or anxiety in any way?

Possible response:

• It is very satisfying for sure. Many people (70%) report tension before biting and then 40% report such a feeling of temporary pleasure after the nail has been bitten.

• Have you tried to stop biting your nails before? If so, what strategies have you used, and how effective were they?

• It's important to address both the habit and its effects on your dental health. There are various strategies we can try to help you reduce nail biting. These include behavioral techniques like habit reversal training, using bitter-tasting nail polish, or finding alternative stress-relief methods. Would you be interested in exploring these options? (Share the fidget ring, pen or Stimmie option)

• Are there specific times of day or activities when you are more likely to bite your nails? (Bring awareness)

• How do you feel about the appearance of your nails and teeth as a result of nail biting?

Possible response:

• Keeping your nails trimmed and filed to keep your nails looking attractive may make you less likely to bite them. Alternatively, you can also cover your nails with tape or stickers.

• Is there anything specific you would like to know or discuss about the effects of nail biting on your dental health?

• How do you feel about the potential of introducing harmful pathogens into your mouth when biting your nails?

I would like to introduce some tools to replace the habit (Replacement Habit). I was thinking you could try a fidget ring or pen or this new stimudent that a dental hygienist invented called the Stimmie that I think could work to help break the habit.

Great! Let's start with this one strategy and meet up again in a couple of weeks to see how it is working for you.

We'll check back in a couple of weeks to discuss your progress and make any necessary adjustments. Remember, changing a habit can take time, and it's okay to have setbacks. I’m here to support you through this process.

In the meantime, I would like you to write a daily journal about your nail-biting and then at the end of the week fill out that Nail Biting Scale Survey.

By responding in this manner, I can effectively support my participants in addressing nail biting, fostering a positive and supportive environment for behavior change.

2nd and 3rd MI Script Call Template

• How have you been since our last session? I’d love to hear about any progress you’ve made or challenges you’ve encountered.

• It sounds like you’ve been feeling…. That’s really important to recognize.

• On a scale of 1 to 10, how important is it for you to stop biting your nails right now?

o What makes it a ----- and not a lower number or higher number?

• What are some things that make it difficult for you to stop biting your nails?

• On a scale of 1 to 10, how confident are you that you can stop biting your nails?

• What would it take for you to feel more confident? What’s one small step you could take this week to build that confidence?

• If you were to successfully stop biting your nails, how do you think your life would be different?• What’s one reason you want to make this change now?

• What’s one small step you’d like to focus on this week to help you reduce nail biting?

• That sounds like a great plan. How do you think you’ll feel after taking that step?

Appendix G: Images

Participant 1: Before

Participant 1: After

Participant 2: Before

Participant 2: After

Participant 3: Before

Participant 3: After

References

- Amin, U., Parveen, A., Rasool, I. and Maqbool, S. (2022). Nail Biting among Children: Paediatric Onychophagia. Inventum Biologicum: An International Journal of Biological Research, [online] 2(3), pp.94–99. Available at: https://journals.worldbiologica.com/ib/article/view/21.

- Baghchechi, M., Pelletier, J.L. and Jacob, S.E. (2021). Art of Prevention: The importance of tackling the nail biting habit. International Journal of Women’s Dermatology, [online] 7(3), pp.309–313. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijwd.2020.09.008.

- Vyas, T. (2017). Effect of Chronic Nail Biting and Non-Nail Biting Habit on the Oral Carriage of Enterobacteriaceae. Journal of Advanced Medical and Dental Sciences Research |Vol. 5|Issue, [online] 5(5). doi:https://doi.org/10.21276/jamdsr.2017.5.5.14.

- Chinnasamy, A., Ramalingam, K., Chopra, P., Gopinath, V., Bishnoi, G. and Chawla, G. (2019). Chronic nail biting, orthodontic treatment and Enterobacteriaceae in the oral cavity. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Dentistry, [online] 11 (12). doi:https://doi.org/10.4317/jced.56059.

- Siddiqui, J.A. and Quershi, S.F. (2020). Onychophagia (Nail Biting): an overview. Indian Journal of Mental Health, 7(2), p.97. doi:https://doi.org/10.30877/ijmh.7.2.2020.97-104.

- Bokrossy, K. (2024). Nail Biting Survey: The Attitudes and Knowledge of Dental Hygienists. [online] rdhu.ca. Available at: https://www.rdhu.ca/partners-resources.

- Ramseier, C. (2010). Health Behavior Change in the Dental Practice. Ames, Iowa: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Kamal, F. and Bernard, R. (2015). Influence of nail biting and finger sucking habits on the oral carriage of Enterobacteriaceae. Contemporary Clinical Dentistry, 6(2), p.211. doi:https://doi.org/10.4103/0976-237x.156048.

About the author

Kathleen is the founder and president of rdhu, a leading professional development company dedicated to transforming the dental hygiene experience. With a passion for lifelong learning, she provides innovative hands-on programs, online education, and team events that empower dental hygienists to elevate their clinical practice. Kathleen is also a strong advocate for integrating research into everyday hygiene care, inspiring clinicians to embrace continuous growth. Learn more at rdhu.ca.