The surgical removal of impacted maxillary third molars is a routine procedure performed by both general dentist and specialists. It is usually associated with a low rate of morbidity and few complications.1 The accidental displacement of the maxillary third molar into adjacent anatomical spaces such as the maxillary sinus, infratemporal fossa, and lateral pharyngeal space has been well documented.2-5 By comparison, displacement into the buccal space has rarely been reported.6-8

We present a case of a maxillary third molar displaced into the buccal fat pad which then migrated anteriorly through the buccal space and present a review of the relevant anatomy of the region.

Case report

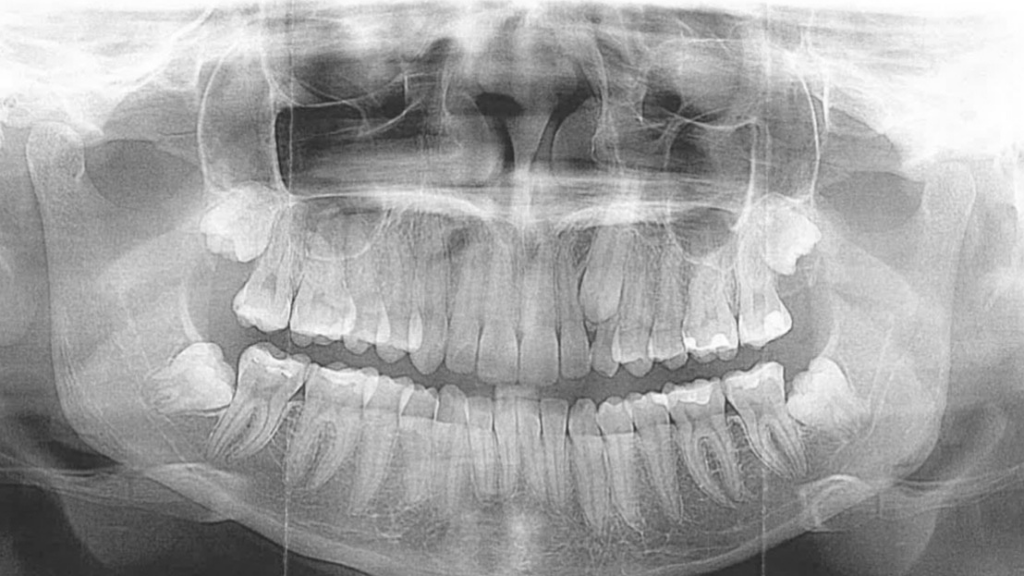

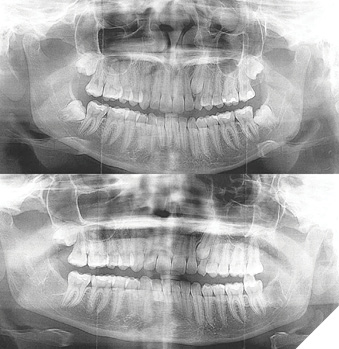

A 20-year-old female underwent third molar extraction with a general dentist under local anaesthesia (Fig. 1A). The lower impacted third molars were surgically removed in an uncomplicated and routine manner. The upper left third molar was then luxated following the elevation of a mucoperiosteal flap. Unfortunately, prior to removal, the tooth disappeared into the adjacent soft tissues, and the general dentist was unable to locate it for removal. The procedure was aborted, the surgical site sutured to secure the mucoperiosteal flap, and a panoramic x-ray taken to locate the tooth (Fig. 1B). The patient was informed of the complication, discharged on antibiotics and a series of follow-up appointments were scheduled for 7, 14 and 28 days following the surgery. On the third follow-up appointment, the patient complained of discomfort in the area, particularly with eating, and to manual palpation the tooth appeared to have moved anteriorly into the soft tissue of the cheek. The patient was referred to the most proximate Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery clinic, located 6 hours from her place of residence.

Fig. 1

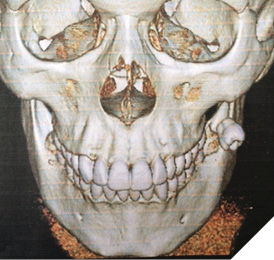

On clinical examination, the tooth was detected in the soft tissue cheek using bi-digital palpation. The patient displayed mild trismus, and the area was very tender to touch. A computed tomography (CT) scan was ordered to define the exact location of the displaced tooth, which revealed the tooth rotated high in the soft tissue of the cheek, adjacent to the remaining maxillary molars (Fig. 2). The patient was taken to the operating room and under general anaesthesia, the displaced and migrated tooth was removed via an intra-oral approach. A mucosal incision was made within the mucoperiosteal fold overlying the tooth, followed by the application of extraoral pressure over the location of the tooth, which expressed the tooth from the buccal space between the buccinator muscle and the superficial fascia. A small amount of pus and granulation tissue was also expressed from the wound. The incision was thoroughly irrigated with sterile saline prior to loose closure with a 3-0 gut suture. The opposite impacted maxillary third molar was also removed in the usual uncomplicated manner. The patient proceeded to a full recovery. During the 2-month follow-up appointment, the patient remained symptom-free with complete soft tissue healing. However, a noticeable soft tissue “dimple” defect was observed in the left cheek (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2

Fig. 3

Discussion

The displacement of a maxillary third molar into the buccal space is usually associated with a distobuccal angulation of the tooth, a lack of bone distal to the tooth, and poor extraction technique combined with decreased direct visualization of the tooth. These factors coupled with poor soft tissue flap design, excessive force application and inadequate instrumentation such as not utilizing an appropriate tissue retractor (Minnesota, Austin, or Laster cheek retractor) can increase the likelihood of tooth or root displacement.

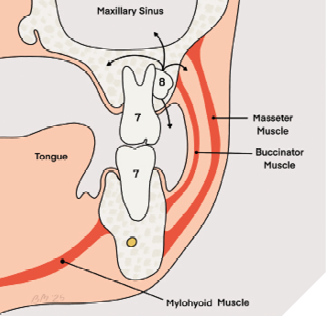

The buccal space is bound by the buccinator muscle and its fascia medially, and the skin of the cheek laterally. The origin of the buccinator muscle extends from the external surface of the alveolar process of the maxilla and inserts onto the alveolar process of the mandible inferiorly, and the anterior border of the pterygo-maxillary ligament posteriorly (Fig. 4). The contents of the buccal space include branches of the buccal nerve, the buccal division of the facial nerve as well as buccal branches of the mandibular nerve, the facial and buccal arteries, minor salivary glands and adipose tissue.9

Fig. 4

The displacement of a foreign body into this space can result in a variety of complications involving many of the contents. For example, damage to the buccal nerve can produce sensory disturbance, injury to the buccal division of the facial nerve or buccal branch of the mandibular nerve can produce motor nerve deficits, bleeding can occur if the facial artery or buccal artery are damaged, and adipose tissue and minor salivary glands can extrude, and may then atrophy or become infected.

The typical management of a displaced molar tooth involves an initial “conservative” attempt to retrieve the tooth from the area where it is believed to be displaced at the time of displacement. This would involve careful probing of the adjacent anatomical space, followed by a careful attempt to grasp the tooth with a fine nose mosquito or hemostat clamp. If conservative removal fails, the area should be closed with resorbable suture, and the patient should be placed on antibiotics to prevent infection and an appropriate pain medication. The area should be imaged with a scout film such as panoramic orthopantomogram which can be compared to any pre-operative film. Ideally, when available, this should be followed by computed tomography (CT) or cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) to localize the tooth in 3-dimensions. Imaging should be performed immediately following the incident to determine the location of the tooth and whether the displacement is likely to affect any adjacent anatomical structures. If the tooth has been displaced into a critical anatomic area, immediate removal is recommended. However, in most situations, the tooth can be left in situ until initial scaring or fibrous encapsulation can occur over the subsequent weeks. This process tends to resist further displacement or migration of the tooth in the region and may facilitate the removal of the tooth. If management is delayed, the practitioner must follow the patient closely due to the increased risk of infection, foreign body reaction, and resultant trismus and patient discomfort.10 In the case presented, the delay in transfer of the patient to a specialist for management was due to the patient being geographically remote from the closest specialist’s office, and this delay may have contributed to some local tissue atrophy and resultant “dimple defect”.

Key Points

Prevention

- Assess anatomy, size, angulation and location of wisdom teeth

- Good intra-operative visibility

- Good assistance

- Correct retraction and retractors

- Good flap design

Displacement

- Abort procedure, alert patient

- Administer prophylactic antibiotics

- Urgent referral to oral and maxillofacial

Conclusion

The accidental displacement of a third molar can occur during a routine surgical extraction, even to the most experienced general or specialist dentist. It is a relatively uncommon complication that is also likely under reported. Prior to any extraction, it is important to ascertain the level of surgical difficulty, have adequate pre-operative radiographic imaging, and possess the technical knowledge and skill to execute the procedure. It is also critical to be familiar with and be able to manage all potential complications associated with the procedure.

Oral Health welcomes this original article.

References

- Brauer, HU, Green, RA, Pynn, BR: Complications during and after surgical removal of third molars Oral Health 103(6):36-48, 2013

- Sverzut CE Trivellato AE, Sverzut AT et al. Removal of a maxillary third molar accidentally displaced into the infratemporal fossa via intraoral approach under local anesthesia: A case report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 67:1316-1320, 2009

- Di Nardo D, Mazzucchi G, Lollobrigida M, et al. Immediate or delayed retrieval of the displaced third molar. A review. J Clin Exp Dent 11(1)e55-e61,2019

- L. McLean, J. Soparlo, J. Armstrong. Teeth Displaced: Teeth at the Time of Surgery. Oral Health 107(6) **** 2017

- Ozer N, Uçem F, Saruhanoğlu A, et al. Removal of a maxillary third molar displaced into pterygopalatine fosaa via intraoral approach. Case Rep Dent Case Rep Dent 2013 Feb 7;2013:392148. doi: 10.1155/2013/392148

- Jain A. Accidental displacement of a mandibular first molar root into buccal space: A unique case. J Stomatol Oral Maxillofac Surg 119: 429-431, 2018

- Kocaelli H, Balcioglu HA, Erdem TL. Displacement of a maxillary third molar into the buccal space: anatomical implications apropos of a case. Int J Oral Maxillofacial Surg.40:650-3, 2011

- Ohba S, Nakatani Y, Kakehashi et al. The migration pathway of an extracted third molar into the buccal fat pad. Odontology 102(2):33942, 2014.

- Kim HC, Han MH, Moon MH et al. CT and MR imaging of the buccal space: Normal anatomy and abnormalities. Korean J Radiol 6(1):22-30, 2005

- P Crespo Reinoso, N Cárdenas, A Caivinagua. Accidental displacement of third molar: A systematic review. Journal of Maxillofacial and Oral Surgery 23 (6), 1449-1454, 2024

About the authors

Bruce R Pynn is Oral Health’s editorial board member for oral and maxillofacial surgery. He maintains a private practice in Thunder Bay, ON. He is Chief of Dentistry, Thunder Bay Regional Health Sciences Center.

Iain A. Nish is a graduate of The University of Toronto in both Dentistry and Oral & Maxillofacial and completed a Fellowship in Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery in Basel, Switzerland. Dr. Nish was a Staff OMFS at Sick Kids Hospital for two decades.