A patient presents to your office with missing maxillary lateral incisors. What do you do? The answer to this is nuanced and dependent on multiple variables. According to a meta-analysis conducted by Polder et al1 the incidence of agenesis of permanent maxillary lateral incisors differs based on continent and gender, with females having an overall 1.37 times higher prevalence than males. In North American Caucasians, the incidence of dental agenesis is 3.2% in males and 4.6% in females. Other than third molars, mandibular second molars are the most affected tooth, followed by maxillary lateral incisors, and then the maxillary second premolars. In general, dental agenesis is more common unilaterally compared to bilaterally, however, agenesis of maxillary lateral incisors is more common bilaterally rather than unilaterally. The incidence of missing maxillary lateral incisors ranges from 1.55% to 1.78%.1 This may not sound very common at face value but these patients present to orthodontic practices on a regular basis. So, what are the treatment options for these patients and how do we as a dental team determine which option to recommend?

Orthodontically, one treatment option is to open space for the prosthetic replacement of the missing incisor(s). The second option for these patients is to close the space for the missing maxillary lateral incisor(s) resulting in canine substitution. In this option the canine replaces the lateral incisor, and the maxillary first premolar takes the place of the canine. There are multiple factors that need to be considered before deciding on one of these two treatment options including the patient’s malocclusion, facial profile, amount of crowding present, the colour and shape of the crown, and smile line.

Opening space for the prosthetic replacement of missing upper lateral incisors is a favourable plan in patients who present with class I or class III malocclusion and generalized spacing between the maxillary dentition,2 as space closure in this instance can compromise your resultant overjet. Another scenario where opening space would be ideal is in a case where there is unilateral agenesis of a permanent maxillary lateral incisor, as it would be quite challenging to aesthetically match a substituted canine on one side and a lateral incisor on the other.2 One last situation where prosthetic replacement would be favourable has to do with the colour and shape of the adjacent teeth. Canines tend to be longer and larger both labiopalatally and mesiodistally compared to lateral incisors, as well as more saturated in colour resulting in a yellow hue.3 Therefore, in patients who have long and pointy canines which are more yellow in colour, it would be advisable to create space for prosthetic replacement.

The advantage to proceeding with a prosthetic plan is that it usually makes the orthodontic treatment shorter and simpler mechanically. However, there are disadvantages with this type of treatment plan. The fixed options to replace missing lateral incisors involve either placing a bridge or an implant. A removable partial denture or a flipper are alternate options as well. With fixed partial dentures, there is a restorative burden placed on the adjacent teeth whether you plan for a conventional or cantilever bridge. Although implant-supported restorations do not suffer this same burden, they do present with their own disadvantages. The first of which being that in younger patients, implants cannot be placed until facial growth is complete, which in females is typically between 16-17 years of age, and in males between 20-21 years of age.2 This is because as facial growth occurs and the mandibular rami lengthen, the teeth must compensate for this growth and therefore erupt in order to remain in occlusion. As implants are osseointegrated, they cannot erupt so if they are placed prior to the completion of facial growth, progressive infraocclusion will cause functional and esthetic issues to arise as the patient ages.4 The most predictable way to determine whether or not facial growth has ceased is by taking serial cephalometric radiographs six months to a year apart and superimposing them in order to illustrate any vertical facial growth over that period of time.5 Furthermore, once orthodontic treatment has been completed, the implant space must be maintained until facial growth has finished. If this time period is short in duration, then an orthodontic retainer with a pontic tooth can be a sufficient means to maintain the space. For patients who have to wait a significant period of time to have the final implant placed, a more fixed option is required, like a bonded retainer wire with a pontic tooth or a Maryland bridge for example. Otherwise, the roots of the central incisor and canine will begin to converge, compromising one’s ability to place the required implant thus requiring orthodontic re-treatment to regain the implant space.6 Lastly in the case of implant treatment, as sufficient mesiodistal space and adequate bone height/width are needed, multiple surgical procedures may potentially be required. This can include bone grafting and/or soft tissue grafting in addition to implant placement.

Alternatively, closing the spaces of missing upper lateral incisors and performing canine substitution is ideal in patients who present with bilateral agenesis, a class II malocclusion, maxillary crowding with minimal mandibular crowding, and small, round canines with their chroma matching that of the central incisors.2 The primary advantage of canine substitution is that the definitive treatment can be completed in the adolescent years as the patient does not have to wait for facial growth to be completed for a final restoration to be placed. Furthermore, as the face grows, even in adulthood, along with aging of the facial structures in our later years, coupled with a dynamic and changing occlusion with progressive wear of the teeth, the dentition erupts in a compensatory manner. By performing canine substitution these long-term adaptations will naturally occur throughout the entire dentition and supporting structures compared to having one or more osseointegrated implants in the esthetic zone. Additionally, from adolescence to adulthood there is a tendency for the maxillary and mandibular incisors to upright. Therefore, implant crowns in this area can become progressively infraoccluded and protrusive over time whereas substituted canines would not suffer the same fate.3 The results of canine substitution are also reasonably stable with proper retention and aesthetically well-accepted by patients.7 In many instances patients even prefer the aesthetics of canine substitution compared with implant replacement of missing lateral incisors.8

When performing canine substitution, the final result can be enhanced when orthodontics is combined with cosmetic dentistry. Firstly, when all anterior teeth are present, the torque (labiopalatal inclination) of the lateral incisors and canines differ, with canines being more upright than lateral incisors. Therefore it is important when performing canine substitution to place the necessary torque on the canines to match that of a lateral incisor. The same is true of the canines and first premolars. Secondly, extrusion of the substituting canines and intrusion of the first premolars can be done to mimic the gingival heights and zeniths of lateral incisors and canines respectively. This can be coupled with esthetic crown lengthening and porcelain veneers to optimize the esthetics of canine substitution. In this way the shape, length and chroma of the substituting canines and first premolars can be made ideal to disguise the fact that the lateral incisors are missing. Composite build-ups or internal bleaching can also be considered as an alternative to porcelain veneers. Lastly, it is also recommended to evaluate the size of the central incisors because frequently with agenesis of the maxillary lateral incisors, the central incisors can also present smaller clinically.3 Therefore, an interdisciplinary approach involving the general dentist or prosthodontist can help to optimize the aesthetics of the final result.

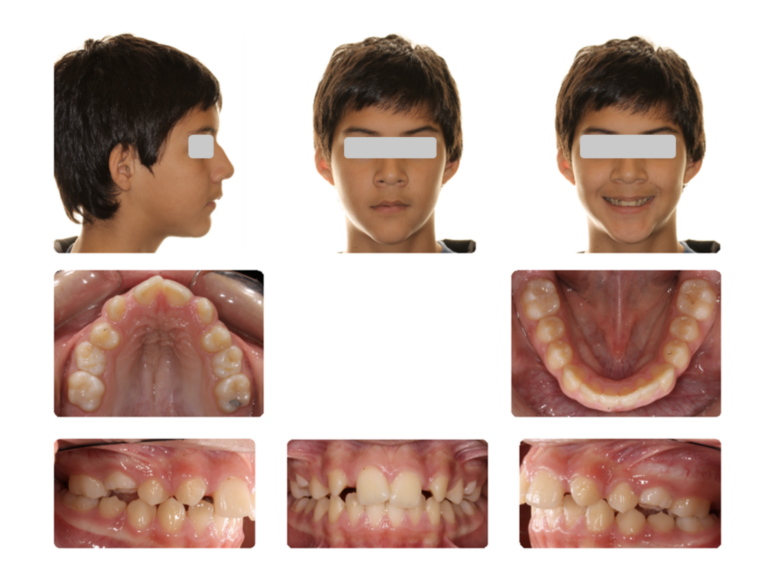

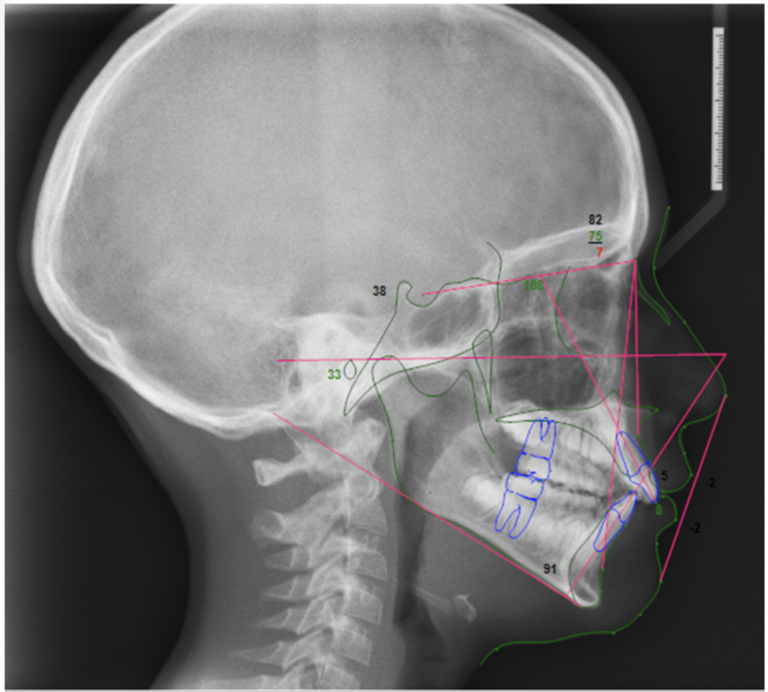

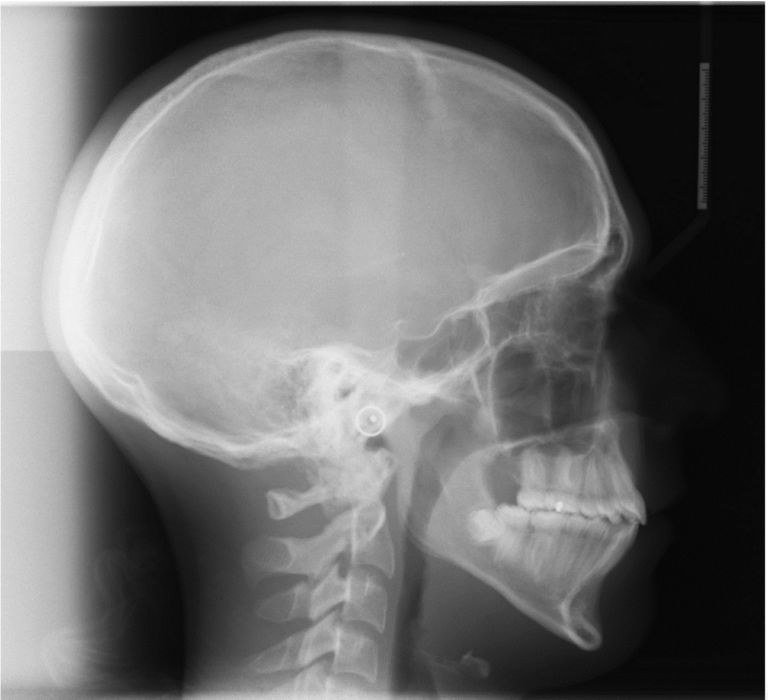

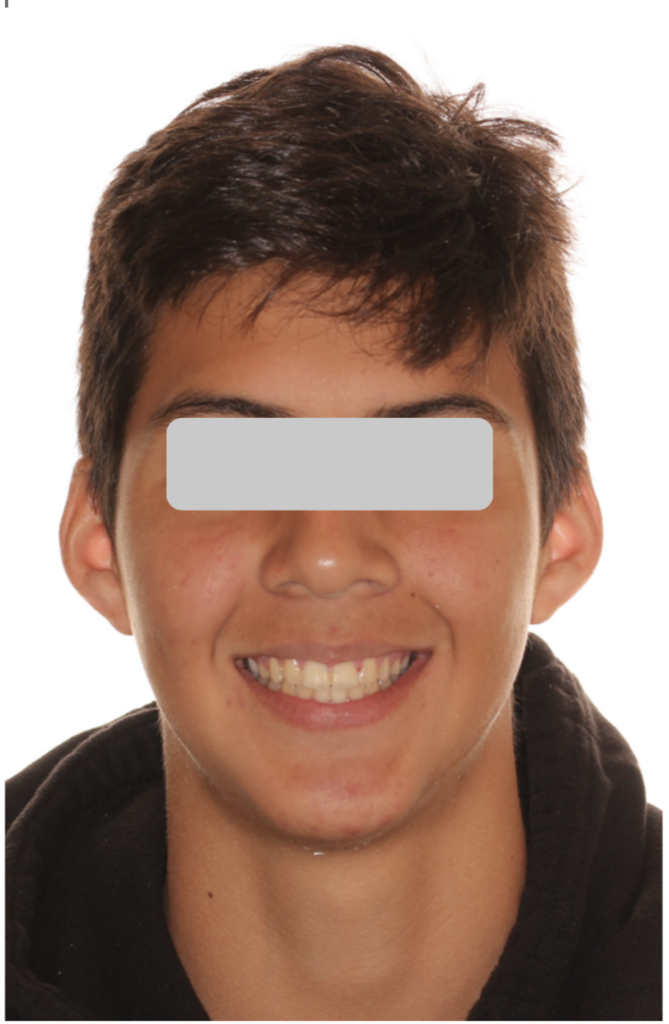

I will now present the complete orthodontic records (Figs. 1-10) of the first patient that I ever treated utilizing canine substitution in order to demonstrate the effectiveness of the treatment plan, as well as to highlight in retrospect what could have been done differently in order to enhance the final result. The patient first presented as a 12 year and 10-month-old male with a class II skeletal discrepancy due to a retrognathic mandible, full cusp class II malocclusion with proclined maxillary incisors, increased overbite and overjet, spacing in the maxillary arch, minimal crowding in the mandibular arch, accentuated curves of Spee and Wilson, retained 55 and 65 with unerupted 15 and 25, and missing 12 and 22. Three treatment options were presented to the patient. The first being extracting 55 and 65 to allow the 15 and 25 to erupt, followed by comprehensive orthodontic treatment with braces performing canine substitution in the maxillary arch and no extractions in the mandibular arch. The second option involved the same extractions of the 55 and 65, but instead of canine substitution, creating space for prosthetic replacement of 12 and 22 coupled with mandibular advancement surgery to correct the skeletal discrepancy. It was advised that if the second option was to be chosen, to start their orthodontic treatment once growth was closer to being finished. Option three was no treatment. After a lengthy discussion of the advantages and disadvantages of all plans, the patient and his family elected for the first option with canine substitution.

Fig. 1

Fig. 2

Fig. 3

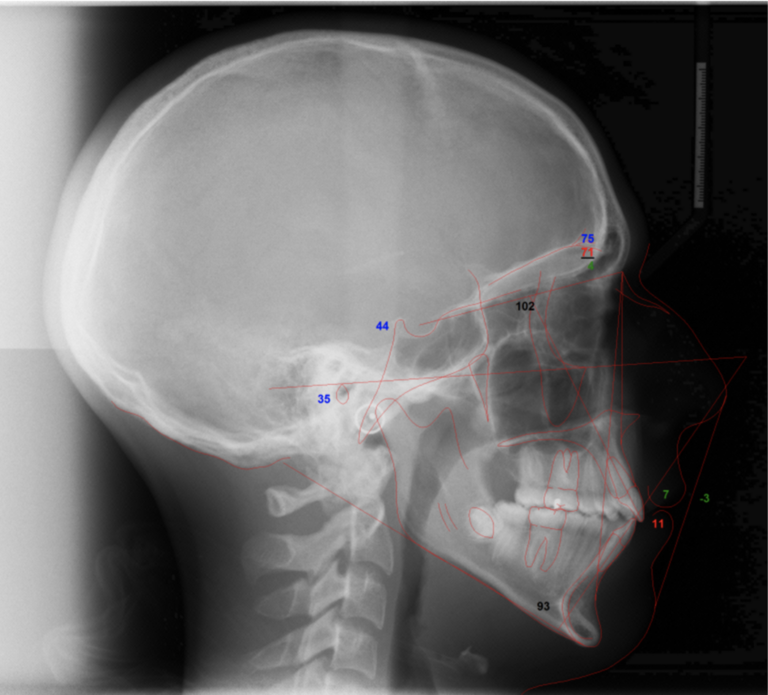

Fig. 4

Fig. 5

Fig. 6

Fig. 7

Fig. 8

Fig. 9

Fig. 10

The Cast-Radiograph Evaluation (CRE) as outlined by the American Board of Orthodontics (ABO) was performed as a means to objectively determine the quality of the finish of this case.9 As can be seen by the final records and the ABO CRE score (Fig. 11), this was a successfully treated case with an orthodontic finish that would more than satisfy the strict requirements of the ABO. The patient finished with ideal incisor inclinations as well as overbite and overjet, class I canine/premolar and full cusp class II molar relationship, and a well-balanced occlusion with an absence of non-working interferences. As can be seen by his final smile photograph (Fig. 12), he also finished with a clinically aesthetic smile with the appropriate torque placed on the substituting canines and first premolars to mimic that of lateral incisors and canines respectively. It is important to note that the superimposition of the initial and final cephalometric radiographs demonstrate the extent of the vertical facial growth that the patient exhibited over the course of his orthodontic treatment (Fig. 10). This outlines the importance of waiting for the completion of facial growth before placing implants in any patient. The patient and family also declined fixed lingual retainers and opted to only have removable retainers for oral hygiene purposes.

Fig. 11

Fig. 12

The final result of this case could be enhanced with porcelain or composite veneers to idealize the shape of the substituting canines and first premolars. As is oftentimes the case with missing teeth, the first premolars are smaller than ideal so porcelain veneers of the substituting teeth could have made their shapes and sizes more aesthetically pleasing. This option was presented to the patient and his family pre-treatment, multiple times throughout orthodontic treatment, and post-treatment. Nevertheless, the patient and his family decided not to pursue these restorations. As a result, I performed enameloplasty on the cusp tip of the 13 and 23 and extruded them to try to mimic lateral incisors. However, I could have extruded the 13 and 23 more and performed the same enameloplasty to better mimic lateral incisors. Luckily, the patient had a low enough smile line to mask the gingival heights. Lastly, not related to the canine substitution, the 41 and 42 could have used more mesial root tip and distal root tip respectively.

In conclusion, when treatment planning for patients presenting with the agenesis of one or both maxillary lateral incisors, there are multiple factors to consider in making the decision to prosthetically replace the missing teeth or to perform canine substitution. Canine substitution is a very viable option and under the correct circumstances can be the optimal treatment plan in terms of both function and aesthetics.

Oral Health welcomes this original article.

References

- Polder, B. J., Van’t Hof, M. A., Van de Linden, F. P., & Kuijpers-Jagtman, A. M. (2004). A meta-analysis of the prevalence of dental agenesis of permanent teeth. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol, 217-226.

- Kokich Jr, V. O., Kinzer, G. A., & Janakievsk, J. (2011). Congenitally missing maxillary lateral incisors: Restorative replacement. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics, 435-445.

- Zachrisson, B. U., Rosa, M., & Toreskog, S. (2011). Congenitally missing maxillary lateral incisors: Canine substitution. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics, 434-444.

- Thilander, B., Ödman, J., & Lekholm, U. (2001). Orthodontic aspects of the use of oral implants in adolescents: a 10-year follow-up study. European Journal of Orthodontics, 715-731.

- Fudalej, P., Kokich, V. G., & Leroux, B. (2007). Determining the cessation of vertical growth of the craniofacial structures to facilitate placement of single-tooth implants. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics, S59-S67.

- Olsen, T. M., & Kokich Sr., V. G. (2010). Postorthodontic root approximation after opening space for maxillary lateral incisor implants. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics, 158.e1-158.e8.

- Robertsson, S., & Mohlin, B. (2000). The congenitally missing upper lateral incisor. A retrospective study of orthodontic space closure versus restorative treatment. European Journal of Orthodontics, 697–710.

- Armbruster, P. C., Gardiner, D. M., Whitley, J. B., & Flerra, J. (2005). THE CONGENITALLY MISSING MAXILLARY LATERAL INCISOR. PART 1: ESTHETIC JUDGMENT OF TREATMENT OPTIONS. World Journal of Orthodontics, 369-375.

- Casko, J. S., Vaden, J. L., Kokich, V. G., Damone, J., James, D. R., Cangialosi, T. J., . . . Bills, E. D. (1998). Objective grading system for dental casts and panoramic radiographs. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics, 589-599.

About the Author

Dr. Jason Zimmerman is a registered specialist in Orthodontics who attended Western University for dental school, and the University of British Columbia for his residency in Orthodontics. He is a Diplomate of the American Board of Orthodontics, has published several papers and currently serves as a reviewer for multiple journals in orthodontics. He and his wife, Dr. Fernanda Barona (periodontist), have recently opened the doors to Atlas Orthodontics and Periodontics, their boutique dual specialty practice in the Oak Ridges/Richmond Hill/King City ON area.