More Magazine–June 1, 2010

by Katharine Davis Fishman

Late last fall I started walking like a penguin. The array of

specialists I waddled in to see–the anesthesiologist, the physiatrist (a

doctor who supervises physical therapy and rehabilitation), the

rheumatologist, the sports-med doctor and finally the back surgeon–were

baffled by my gait and the increasingly intense throbbing in my left

buttock.

At 11 o’clock the night of the back- doctor visit, I tripped on a

rug. As I slid down the wall, my upper thigh shot out to a 45-degree

angle, and I felt an excruciating pain. “Joe, call 911!” I shouted to my

husband.

My femur, or thigh bone, had fractured. Doctors implanted a titanium

rod and two screws, and I spent three weeks,including rehab,at the

nearest regional trauma center.

Two months after the accident, when I showed up (still using a

walker) for follow-up care at Hospital for Special Surgery in New York

City, I learned that the fracture had probably been caused by

bisphosphonates. Those were the what-a-nuisance drugs that had me

getting up early, swigging down a little pill with a big mug of water

and–forbidden to eat for the next 30 to 60 minutes–enviously watching my

husband enjoy his muffin, all in the interest of avoiding . . . hip

fractures! After an osteoporosis diagnosis, I’d swallowed Fosamax for

nearly 10 years, stopped for a year after I developed an ulcer, then

spent three years on Boniva, the Sally Field drug. All this pill taking

helped; I moved from osteoporosis to osteopenia, a milder condition. And

yet a silly at-home accident had just broken my femur.

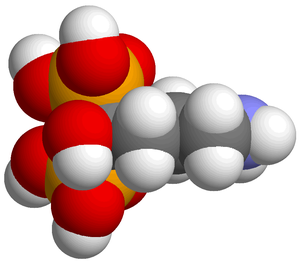

Image via Wikipedia

Around 2004, Joseph

Lane, MD, an orthopedist who’s chief of the Metabolic

Bone Disease Service at Hospital for Special Surgery, began to

notice similar strange events among some patients who’d been taking

bisphosphonates for about six years. Two women stand out particularly in

Lane’s memory. “One had been complaining of thigh pain for three

months,” he remembers. “She’d had two epidural injections for back pain,

and while she was in a swimming pool she broke her femur, simply by

turning around. Number two is a woman who was getting on a plane to go

visit her grandchildren. Similar story: She had earlier complained of

sciatica, but her doctors didn’t take an X-ray. Instead, they gave her

an MRI and an epidural injection. Then, the day of her flight, she

climbed the stairs during boarding and broke her femur going up.”

In 2005, Lane read an article in the Journal of Clinical

Endocrinology and Metabolism that jibed with what he’d been seeing.

A team at the University of Texas in Dallas and at Henry Ford Hospital

in Detroit had biopsied nine patients with osteoporosis or osteopenia,

most of whom had been taking alendronate–Fosamax’s generic name–for

three to eight years and had “spontaneous nonspinal fractures” in odd

places that took an unusually long time to heal. Bone biopsies showed

“minimal, or no, identifiable osteoblasts” (the buildup cells) and low

breakdown activity–a syndrome that became known in lay language as

frozen bone.

This was a small study with no control group, and some patients were

taking drugs besides alendronate. But the authors called for more

research “to determine how long bisphosphonates can safely be given.”

Lane and four colleagues reviewed the records of all patients admitted

to its trauma center from 2002 to 2007 with femur-shaft fractures that

were “low energy,” meaning they had been incurred while the person was

simply standing around (or splashing in a swimming pool).

The 70 trauma center patients whose cases they reviewed had all

suffered from what’s technically known as an atypical subtrochanteric

femur -fracture–and more than a third had been taking Fosamax, the

bisphosphonate that’s been available the longest. Three quarters of

these Fosamax patients shared a particular radiographic pattern: a

simple horizontal or diagonal fracture with a sort of beaky overhang of

bone. Their X-rays looked exactly like the one I was presented with two

years later. The pattern was 98 percent specific to Fosamax users, and

those who displayed it had been using the drug significantly longer than

those whose breaks did not look like that. A follow-up study matching a

smaller group of patients who had femur fractures with a control group

of subjects who had ordinary hip fractures showed roughly similar

results: Nearly a third of those with thigh fractures were on Fosamax,

as opposed to one ninth of the hip patients; two thirds of the thigh

patients on Fosamax showed the pattern, and they tended to have been on

Fosamax longer than those with hip fractures.

Meanwhile, more reports were coming out, one from Singapore and one

from Japan. Researchers hypothesized that bisphosphonates produce bone

that is brittle and fracture-prone and that the thigh pain comes from

little stress fractures that don’t heal but rather accumulate and build

up to one big kahuna of a break. The patients Lane sees are active women

seven to 10 years younger than those who break their hips (which

happens on average at age 82). “Every woman I’ve seen has been out there

shopping, working, running after her grandchildren, doing stuff,” he

says. “These are not couch potatoes. I have never seen this kind of

fracture in a nursing home patient.”

Two New York teams, one at Columbia and another (including Lane) at

Hospital for Special Surgery, recently presented small controlled

studies of postmenopausal women with osteoporosis at the 2010 annual

meeting of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. The HSS team

biopsied osteoporotic bone while the Columbia group analyzed the

patients’ scans, and both studies buttress the theory that long-term

bisphosphonate use alters bone properties so as to increase the risk of

atypical femur fractures.

The bottom line: Experts agree that bisphosphonates prevent a lot of

fractures in elderly patients with severe osteoporosis, and more of

these people should be getting the drugs. If you are in your fifties and

have a mother in her eighties, most likely she is a better candidate

for bisphosphonate therapy than you are. Before taking these drugs,

consult with your doctor to be absolutely sure you have real

osteoporosis. If you do begin this course of therapy, get checked after

three to five years to see if you still need it.

Read the full article at more.com.