Abstract

Malpostioned dental implants are a common challenge in implant dentistry with a potential to compromise function, aesthetics and the overall treatment success. This case report discusses the management of a malpositioned implant in the posterior mandible with a comprehensive approach, including long-term provisionalization for assessment. A 53-year-old female patient presented with compromised chewing function and dissatisfaction with her provisional fixed implant-supported prosthesis. Challenges included implant malposition, screw channel exposure on the buccal, food impaction, and history of implant loss due to peri-implantitis. The treatment plan involved addressing these challenges through a diagnostic wax-up and its intraoral mock-up followed by adjustments to the provisional prosthesis based on the diagnostic wax up, and patient involvement. This case highlights the importance of provisional prostheses in diagnosing and planning restoration of malpositioned implants. Provisional prostheses allow patient and dentist to assess function and appearance, which may direct modification of treatment plan.

Comprehensive treatment planning in implant dentistry is crucial to avoid and manage possible complications such as implant malposition.1 However, implant malposition is common in clinical practice. Restoring a malpositioned dental implant can be complex and may involve a thorough clinical and radiographic evaluation, careful planning, prosthodontic management, and secondary surgical intervention including the replacement of the malpositioned implant. The exact approach to restoration will depend on the specific factors such as the degree of malposition and the proximity to the surrounding anatomical structures. Severely malpositioned implants may be considered for removal and replacement with a new implant in an optimal position.2 The insertion of a provisional prosthesis to assess the restorability of a malpositioned dental implant is critical during the treatment planning stage: it can facilitate the evaluation of chewing and speech function, esthetics, patient comfort, and the response of the surrounding soft tissue. Furthermore, it allows patient to experience the feel and function of the planned definitive restoration, enhancing the predictability of the final treatment outcome.3

Case Report

A 53-year-old female patient, ASA II, presented to the Graduate Prosthodontics Clinic seeking improvement in compromised chewing function due to multiple missing teeth on the left side. She had partial edentulism restored with a provisional removable partial denture (RPD) in the maxilla and a provisional implant-supported fixed dental prosthesis (IS-FDP) 34-35-36 in quadrant 3. The implants in quadrant 2 were placed and being managed elsewhere. The patient had a history of implant loss in quadrant 3 due to peri-implantitis.

Chief complaint

Patient’s chief complaint was compromised chewing function due to multiple missing teeth on the left side. She reported not wearing the maxillary provisional RPD due to discomfort. There was significant food impaction underneath the provisional IS-FDP, which was difficult to clean with floss due to a lack of access. The patient was not satisfied with the buccal exposure of the implant screw access channel at 35. The patient indicated that the original treatment plan was a four-unit bridge supported by three implants in the mandibular left, but the current provisional prosthesis only restored three missing teeth. The patient requested to add an additional tooth to the definitive prosthesis.

Medical history

The patient had hypothyroidism diagnosed in 2004, which was well-controlled with levothyroxine. She had no allergies to medications and had sinus surgery in 2005. She was a non-smoker.

Dental history

The patient had implants 36 and 37 placed in 2008 and restored with splinted implant-supported crowns in 2009, which she was never comfortable with. Severe bone loss around both implants was noticed in 2014, and both were removed in 2015. New implants 34, 36 and 37 were planned for placement and restoration with IS-FDP 34-X-36-37. However, implants 34, 35 and 36 were placed in conjunction with bone grafting in November 2020, with implant 35 located buccally to the planned location. The patient experienced temporary paresthesia in the left mandible after implant surgery which resolved in February 2021. A provisional IS-FDP was fabricated based on the tooth set up during the treatment planning stage and inserted with the implant screw channel exposed on the buccal of 35. The patient reported food impaction under the bridge, especially on the lingual side, which was difficult to clean with floss. Implants 26 and 27 were placed elsewhere in August 2021 and were planned to be uncovered and restored there. A maxillary provisional RPD was provided by the same external team, but the patient never wore it. The patient was referred to the Graduate Prosthodontics Clinic for the restoration of implants 34, 35 and 36.

Initial presentation

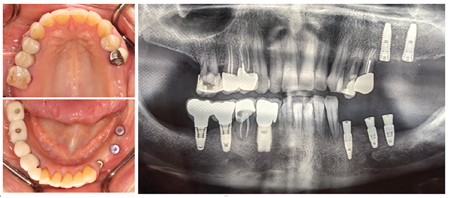

Initial intraoral photos and the panoramic radiograph during the pre-prosthodontic check are shown in Figure 1. The patient was partially edentulous in both the maxilla and mandible. Implants 26 and 27 were buried with healthy soft tissue covering in quadrant 2. Implants 34, 35, and 36 healed well with healthy soft tissue surrounding the healing abutments. However, the panoramic radiograph indicated obvious bone loss at the neck of implant 36, especially on the distal side, the proximity of implant 35 to the mental foreman, and the relatively deep placement of implant 34 compared to tooth 33 and implant 35. The existing provisional IS-FDP 34-35-36 was originally fabricated and delivered to assess the restorability of the implants 34, 35 and 36 due to their proximity to anatomical structures and the paresthesia history after implant surgery. Because the provisional prosthesis was fabricated based on the tooth set up in the treatment planning stage, the implant screw channel was exposed on the buccal of 35 with significant metal showing due to the buccal placement of implant 35 (Fig. 2). The provisional prosthesis was lingually oriented compared to the alveolar ridge with a significant undercut on the lingual side, which facilitated food trapping under the bridge. Furthermore, the emergence profile and the contour of the bridge contacting the soft tissue did not provide flossing access, as shown in Figure 2. Gradual bone loss was noticed around implants 35 and 36. Other treatment planning issues included an over-erupted opposing tooth 24 resulting in a slightly irregular occlusal plane and limited restorative space for tooth 34. Severe periodontal bone loss was observed at teeth 24 and 25, with slight mobility, heavy direct restorations and significant recurrent decay of teeth 16, 15, 14 and 24, and periapical radiolucency of teeth 16 and 25.

Fig. 1

Fig. 2

Challenges

This case presented multiple challenges, including:

- Malpositioned implant 35 and its uncertain restorability

- Exposure of the implant screw channel on the buccal surface of 35

- Food trapping beneath the provisional implant-supported bridge 34-35-36

- Provisional prosthesis 34-35-36 shorter than planned

- Bone loss around implants 35 and 36

- History of implant loss in quadrant 3

- Over-erupted opposing tooth 24

- General dental treatment needs in the opposing jaw (severe periodontal bone loss at teeth 24 and 25; heavy direct restorations with significant recurrent decay of teeth 16, 15, 14 and 24; and periapical radiolucency of teeth 16 and 25)

- Anatomic restriction (proximity to mental foramen) in the 35 site.

Management

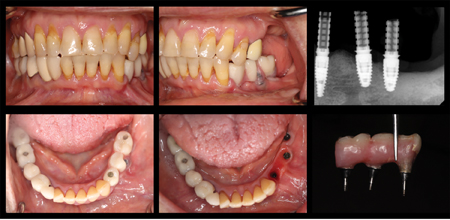

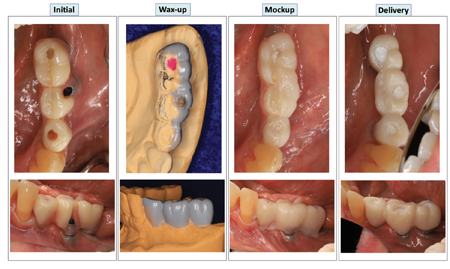

After reviewing and discussing the challenges with the patient, the following treatment plan was accepted and implemented. First, the over-erupted opposing tooth 24 was adjusted with reduction guide to level the occlusal plane and provide more restorative space. The wax-up of provisional implant-supported splinted crowns 34-35-36 was optimized to cover the buccal screw channel exposure at 35 and lingual contour was modified to prevent food trapping and to facilitate cleaning access as demonstrated in Figure 3. A short distal extension of the provisional prosthesis was added to establish proper occlusion with the opposing planned IS-FDP 26-27.

An intraoral mockup was completed to assess the treatment outcome and evaluate the patient’s satisfaction. Modifications and improvements were made to the wax-up and provisional prosthesis until the patient was pleased, especially with the appearance of the implant screw channel. A new provisional IS-FDP 34-35-36 was then fabricated in PMMA and delivered (Fig. 3 and 4).

Fig. 3

Fig. 4

Long-term observation with the provisional IS-FDP in place was recommended and accepted by the patient while waiting to plan for further treatment. Tooth 16 was extracted during the treatment process due to a periapical lesion and limited remaining tooth structure. The patient preferred to preserve teeth 15, 14, 24 and 25 and underwent or will undergo direct restoration replacement and other necessary treatments. An updated CBCT was taken to assess the current implant and bone condition in quadrant 3. Implant removal and replacement of 35 and 36 were considered, and possible risks and complications were discussed with the patient. Further treatment will be carried out based on patient consent.

Discussion

Malpositioned dental implants can pose various challenges for patients and dental professionals. These challenges can affect function, esthetics and the overall success of implant-supported restorations. In this case, we utilized a provisional implant-supported prosthesis to assess the restorability of a malpositioned implant in the posterior mandible. This approach is critical for facilitating treatment planning.

Malpositioned implants can lead to uneven occlusal force distribution. In the anterior region, implant malposition can disrupt the smile’s harmony and natural appearance due to uneven gingival contours and potential gingival recession or visible implant.4 Speech articulation may also be affected. Malpostioned implants can create inaccessible areas that are challenging to clean, increasing the risk of plaque buildup, gingival inflammation, and potential peri-implantitis. Maintaining oral hygiene around malpositioned implants can be more complex, requiring specialized techniques or tools to ensure long-term implant health. Severe malposition can compromise implant’s long-term stability, potentially leading to implant failure.

Prosthodontic restoration of malpostioned implants may require the use of angulated abutments,5 angulated screw channels, customized abutments, cement-retained restoration, and modification of prosthesis design to achieve functional and esthetic outcomes.6 Correcting severely malpositioned implants often involves additional surgical procedures, such as implant removal and replacement at an optimal angle and location, bone grafting, and soft tissue manipulation. Collaboration between the surgical team, the prosthodontist and the dental technician is essential.7 These procedures can increase treatment time, cost, and complexity and may have a psychological impact on patients, affecting their self-esteem and confidence, especially when esthetics are compromised. Achieving long-term success with malpostioned implants can be challenging, requiring close monitoring, maintenance and potential future intervention to address complications.

In this case, implant 35 was placed buccally, and we applied the provisional prosthesis to evaluate its restorability with optimal aesthetics and hygiene access. Patient feedback during this stage was crucial for making necessary adjustments before proceeding to fabricate the definitive prosthesis.8 This approach saved time and resources by identifying and resolving potential complications before the definitive restoration phase, increasing the predictability of the final treatment outcome.

Conclusion

Management of malpositioned implants can be difficult. It is often unclear at the start if an aesthetic, functional and hygienic prosthesis can be fabricated despite the implant malposition. Diagnostic wax-ups and provisional prostheses have numerous general uses and can be valuable in providing critical diagnostic information in the assessment and treatment planning for the restorability of malpositioned implants. Diagnostic wax-ups and provisional prostheses offer a preview of the final restoration, facilitate patient involvement, and enable adjustments to be made prior to the fabrication of the definitive restoration. This approach is also valuable in cases where the long-term biologic viability of the implant(s) is in question. In our case, a new transitional fixed prosthesis confirmed restorability of a malpositioned implant and allowed the patient to function with an aesthetic and hygienic restoration while the supporting compromised implant is being re-assessed on a long-term basis.

Oral Health welcomes this original article.

References

- Goodacre CJ, Kattadiyil MT. Prosthetic-related dental implant complications: etiology, prevention, and treatment. Dental Implant Complications: Etiology, Prevention, and Treatment. 2015 Nov 16:233-58.

- Bidra AS. Prosthodontic management of malpositioned implants and implant occlusion complications. Dental Implant Complications: Etiology, Prevention, and Treatment. 2015 Nov 16:559-71.

- Siadat H, Alikhasi M, Beyabanaki E. Interim prosthesis options for dental implants. J Prosthodont. 2017 Jun;26(4):331-338.

- Martin WC, Pollini A, Morton D. The influence of restorative procedures on esthetic outcomes in implant dentistry: a systematic review. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2014;29 Suppl:142-54.

- Cavallaro J Jr, Greenstein G. Angled implant abutments: a practical application of available knowledge. J Am Dent Assoc. 2011 Feb;142(2):150-8.

- Monaco C, Scheda L, Arena A, di Fiore A, Zucchelli G. Malpositioned implant in the esthetic area: the peri-implant plastic surgery and angulated welded abutment approach. Int J Prosthodont. 2023 May;36(2):228-232.

- de Avila ED, de Molon RS, de Barros-Filho LA, de Andrade MF, Mollo Fde A Jr, de Barros LA. Correction of malpositioned implants through periodontal surgery and prosthetic rehabilitation using angled abutment. Case Rep Dent. 2014; 2014:702630.

- Alzahrani AAH, Gibson BJ. Scoping review of the role of shared decision making in dental implant consultations. JDR Clin Trans Res. 2018 Apr;3(2):130-140. Res.

About the Authors

Dr. Cui Cui received her DDS followed by a Master in Clinical Stomatology from China and a Ph.D. in Dental Science from McGill University in 2015. She served as the ITI Scholar at Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital and SickKids Hospital from 2016 to 2017. Dr. Cui Cui recently completed her Prosthodontics residency at the University of Toronto. She is a Fellow of the Royal College of Dentists of Canada.

Dr. David Chvartszaid is an Assistant Professor at the University of Toronto and the chief-of-dentistry at Baycrest Hospital (Toronto). He is a specialist in Prosthodontics and Periodontics and holds master’s degrees in both from the University of Toronto. David Chvartszaid is a past director of the Graduate Prosthodontics program at the University of Toronto and is a past president of the Association of Prosthodontists of Canada.