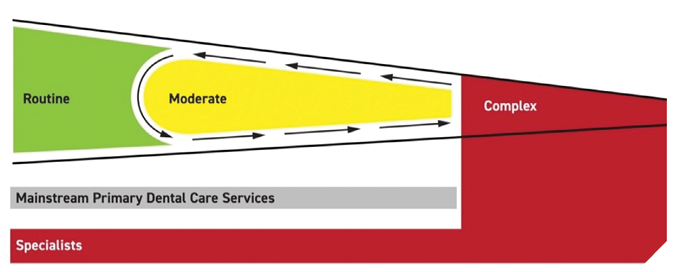

In addition to financial and physical barriers in accessing care, people living with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) are on a spectrum for their ability to tolerate dental procedures (Fig. 1).3 Oral Health Care Provider’s ability and willingness to treat are factors determining the delivery of oral health care. Many oral health care providers feel they lack training and are not willing to spend the additional time to manage and treat IDD patients. For example, patient behaviour may be uncontrollable, and they may not tolerate treatment and withdraw from delivery of restorative procedures. However, they may be able to tolerate some form of hygiene services. They may have pre-existing medical co-morbidities rendering in-office appointments unsafe. Some IDD patients fit into the “complex care” (red) area of Figure 1. Here, hospital dentists are labelled as specialists.

Fig. 1

Many IDD patients may be able to tolerate some form of in-office hygiene scaling. Due to their ongoing oscillating behaviour, on some days they may tolerate a restorative procedure. An important value for these patients is to have a “dental home” for routine visits where an oral health care professional can perform exams and alert family/caregivers of any changes.

The use of general anaesthesia as an intervention goes beyond the scope of routine behaviour management techniques like desensitization, anti-anxiety medications, therapeutic immobilization and sedation.

Oral health care planning (i.e., treatment planning) must consider each patient’s values and preferences as well as the medical, dental, psychological and social manners by which treatment may impact them.3

Listed below is a typical sequence of steps taken by hospital dentists for delivering care under general anaesthesia:

1) A dentist receives a referral for dental treatment under General Anaesthesia (GA) in the hospital.

2) A dental secretary/assistant arranges for a dental consultation with the Power of Attorney (POA) for explanation of the risks, benefits, nature of treatment, when the treatment will be performed, and how long treatment appointment is estimated to be. At this consultation, medical and dental history taking is completed, hospital patient questionnaires, and hospital consent are completed, and there is an explanation of fees and benefits. This is the beginning of the consent process for dental treatment.

3) The dentist of record makes a request for a Cumulative Patient Profile from the primary care physician (usually by fax).

4) The hospital’s administrative staff book an in hospital pre-operative assessment conducted by an anesthesiologist or internist to evaluate patient fitness for general anaesthetic. This is where consent for GA is given.

5) After this assessment, the dentist may be required to consult with the anaesthesia team (by, phone, email or fax).

6) Dental assistant books an operating room (OR) date.

7) On the day of treatment, the patient arrives with their POA and support. The dentist greets the patient with their family, and explains consent again (as initiated in #2 above).

8) At this time, the patient may require preoperative sedation to manage their behaviour. There may be a need for the dentist to additionally consult with anaesthetist/internist, as well as the pre- and post-op nursing team. If necessary, pre-operative sedation (to help in the induction of GA) is given by the OR nursing team acting on the anesthesiologist’s instruction.

9) The patient is brought into the operating room and general anaesthesia is induced. Briefing and check-in procedures are articulated by the dentist to the operating room team (OR safety requirements), and then dental care is delivered in the following manner: complete oral examination, full radiographic series taken; patient-centred treatment planning, subgingival scaling, application of fluoride and anticariogenic agents, caries eradication and placement of dental restorations, extractions, and any other required dental treatment is undertaken.Complex multi-appointment procedures are avoided with a view to minimize exposures to general anaesthetics and to limited OR availability. The treatment goal is to work towards a maintainable, comfortable, and functional state of oral health.Immediately following the completion of treatment in the OR, a debriefing with the operating room team is articulated by the dentist.

The dentist explains the treatment performed and the post-operative instructions to the waiting family/case worker/POA. The family is then invited into the recovery room, so the patient can wake up to familiar faces. The dentist is to be available after hours for unforeseen post-operative complications.

10) The next day, a follow-up phone call (concern/care call) is made by the dentist. The dentist encourages regular in office visits with the patient’s current community dentist. It is highly recommended that the patient see their dentist regularly (primarily for oral health risk assessment, hygiene care and oral hygiene instruction) or that arrangements are made for referral to an office that is willing to do this.

Here are two examples of a typical hospital OR patient. The first speaks to managing complex medical co-morbidities, and the second to managing severe behavioural disorders.

Case 1: A 30-year-old male was referred for hospital dental treatment under general anaesthesia after experiencing a severe drop in blood pressure following an in-office dental procedure at which time patient was rushed to a hospital emergency department.

The patient’s medical history included a developmental non-verbal disorder, blindness, and obesity. He was diagnosed with adrenal crisis, anemia, anxiety, behavioural disorder, congenital hypothyroidism, depression, shingles, leukoplakia, pancytopenia pituitary disease, and seizures.

His dental treatment plan consisted of extensive subgingival scaling, multiple dental restorations, and multiple dental extractions.

During treatment, patient vital signs were managed pharmacologically. Bleeding was controlled in the usual manner and additionally, onsite blood draws were taken with real time lab analysis allowing for monitoring the administration of intravenous platelets.

This patient was successfully treated with the collaboration of the entire hospital operating room team (i.e., dental assistant, anaesthetist, internal medicine physician, operating room nurses, peri-operative nurses, and hospital staff).

Patient behaviour had improved significantly in the days following surgery, most likely because he no longer was experiencing pain.

Case 2: A 17-year-old male was referred for hospital dental treatment under general anaesthesia because he would run away (sometimes into the street) every time he was in a medical/dental environment. He had not seen a physician nor a dentist in over 10 years.

He was a tall, strong individual (196 cm, 104 kg). He had global developmental delay and behavioural disorder. He did not speak.

Despite being heavily sedated orally when leaving home, once in the hospital parking lot, he would not get out of the car.

Three uniformed hospital security personnel went to car and managed to escort the patient into the operating room waiting area. Here he was restrained by additional hospital employees (porters and nurses), then given a high dose of a sedative intramuscularly. He was then wheeled on a hospital bed into the OR.

This patient was successfully treated largely because of the collaborative efforts of non-medical hospital personal (security, porters and administrative staff) who developed a co-ordinated plan with the dental assistant to get patient into the operating room.

Fig. 2

These two examples require co-ordination of not only the treatment team, but also other hospital staff. The entire team includes the treating dentist, dental assistant, operating room nurses, operating room anaesthetist, hospital internal medicine physician, intake and recovery nurses (peri-operative nurses), operating room porters, hospital security and administration staff.

A team is only as strong as its weakest link. Enthusiasm and willingness to treat are pre-requisites. Time required to treat is affected by team culture. As with all teams, efficiency improves with repetition. The more cases done, the better the team becomes, and a strong culture has a chance to develop.

Access to oral health care for IDD patients does not come without prerequisites. There has to be a culture of willingness to treat. The hospital has to dedicate operating room time. Dentists, dental assistants, physicians, nurses and administrative staff need training to feel comfortable in the presence of IDD patients. Health care providers must be properly remunerated. Private and government sponsored dental benefits need to recognize the demands of additional time and responsibility when treating exceptional patients.

There is a need for promotion of collaborative and interdisciplinary care between oral health care professionals, other health care providers, personal caregivers and agencies that work with individuals with special needs.

Placing people, educational institutions, associations, agencies and governments at the centre of integrated services emphasizes commitment to fairness, social justice, participation and intersectoral collaboration. (5) More work needs to be done in Canada to address the lack of willingness to treat, not just by Oral Health Care providers, but by governments when developing provision for access to infrastructure (e.g., hospitals)., Educational institutions should develop curricula for students to properly prepare them for exposure to IDD patients. There should also be greater interprofessional collaboration between the medical and dental communities, and a fostering of understanding in the community that recognizes highest quality oral health care goals while respecting dignity and inclusion for all persons living with disabilities.

In closing, please allow me to share a personal note. The overwhelming gratitude from families who have loved ones living with IDD cannot be reduced to writing. I have found profound happiness practicing hospital dentistry.

Oral Health welcomes this original article.

References

- Oral healthcare disparities in Canada: filling in the gaps Ben B. Levy & Jade Goodman & Antoine Eskander

- Access to Oral Health Care for Individuals with Developmental Disabilities: An Umbrella Review Keith Da Silva, DDS, FRCD(C) Julie W. Farmer, RDH, MSc Carlos Quiñonez, DMD, MSc, PhD, FRCD(C) Prepared for the Federal-Provincial-Territorial Dental Directors Working Group October 2017,

- The use of general anaesthesia in special care dentistry: A clinical guideline from the British Society for Disability and Oral Health Andrew R. Geddis- Regan1, Deborah Gray, Sarah Buckingham, Upma Misra Carole B

- Towards a Common Language for Functioning, Disability and Health ICF; WHO, Geneva 2002

- Integrating the Social Determinants of Health into Health Workforce, Education and Training; WHO, Geneva 2023

About the Author:

Dr. Steve Lipinski is on professional staff at Trillium Health Partners, Credit Valley Hospital, Mississauga, Ontario. He is a Board member of the Canadian Society for Disability and Oral Health. He may be reached at drlipinski@lovemysleep.ca