ABSTRACT

The use of Botulinum toxin type A (BTX-A) has increased in healthcare professions due to its expanding range of applications. The reported case series, demonstrated a decrease in masticatory myofascial (muscle) pain. A narrative review of the literature in the past five years was subsequently completed which supports the use of Botox in the management of temporomandibular disorders (TMD)-related pain originating from a muscular/myofascial origin.

CASE SERIES

Ten TMD-related pain patients (8 females, 2 males; mean age: 38 years; median age: 37 years, age range: 22-53 years). TMD diagnosis of myofascial pain was obtained in accordance with Research Diagnostic Criteria for TMD classification.1 Palpation examination of neck and shoulder muscle revealed pain/inflammation. All TMD patients were injected with different doses of therapeutic BTX-A. No significant adverse reactions were reported post-injection. All cases presented in this report had previously received conservative therapy in the form of an oral appliances therapy, and physiotherapy which had reduced but not eliminated their masticatory myofascial (muscle) pain. Subjects were assessed for pain resolution using Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) for pain response from zero (no pain) to 10 (severe pain), pre- and post- BTX-A injection.

PROCEDURE

Patients were injected with different doses of therapeutic Botox (BTX-A Allergan DIN: 01981501, 100 units per vial). BTX-A was reconstituted using 0.9% bacteriostatic sodium chloride (DIN: 00037818- Pfizer Canada). Bilateral muscle injections included the temporalis-, masseter-, suboccipital-, and shoulder-muscles (Table 1). Subjects were followed up two weeks after injection and scheduled for subsequent injections at 3 month intervals over 20 months.

Table 1: Patient demographics, diagnosis and dose administered.

| Patient ID | Age | Gender (female = F, male = M) | Diagnosis (DC/TMD) | Additional Diagnoses | BTX-A Dose (Units) |

| 1 | 33 | F | Myofascial pain | Neck- and shoulder- pain | 50 |

| 2 | 34 | F | Myofascial pain | Neck- and shoulder- pain | 143 |

| 3 | 51 | F | Myofascial pain | Neck- and shoulder- pain | 70 |

| 4 | 23 | F | Myofascial pain | Neck- and shoulder- pain | 100 |

| 5 | 22 | F | Myofascial pain | Neck- and shoulder- pain | 96.5 |

| 6 | 47 | F | Myofascial pain | Neck- and shoulder- pain | 55 |

| 7 | 52 | F | Myofascial pain | Neck- and shoulder- pain | 70 |

| 8 | 45 | F | Myofascial pain | Neck- and shoulder- pain | 65 |

| 9 | 45 | M | Myalgia | Neck- and shoulder- pain | 77.5 |

| 10 | 29 | M | Myalgia | Neck- and shoulder- pain | 85 |

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

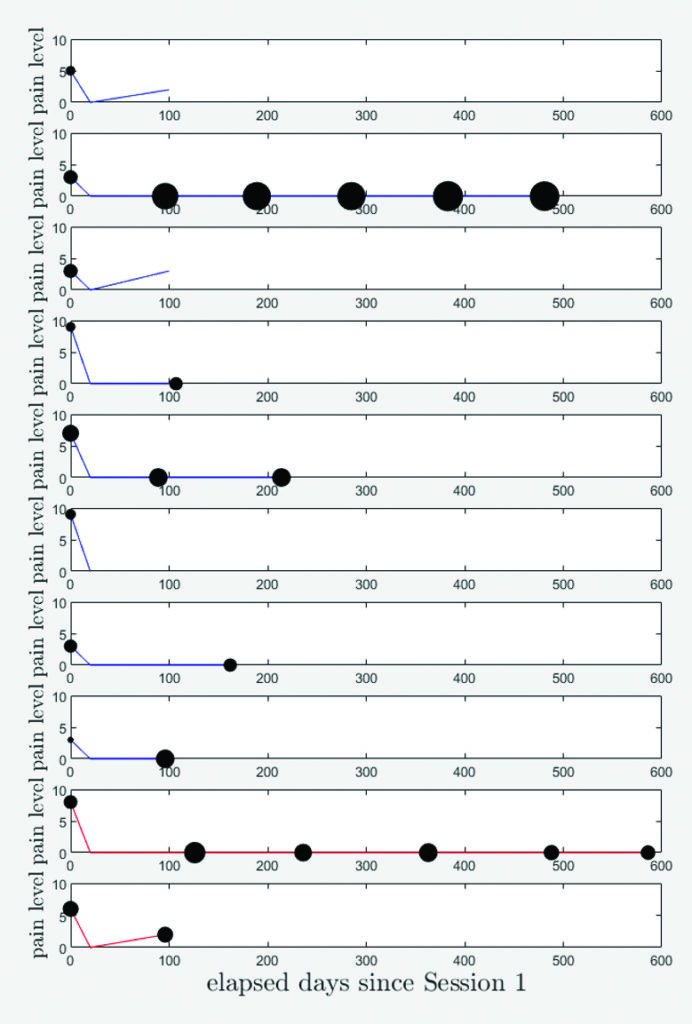

Therapeutic BTX-A injection of the ten subjects was highly effective in female subjects. Females appear to have a relatively higher improvement in pain response compared to males (75% versus 50%). Regular administration of BTX-A at scheduled 3 month intervals appears to have better outcome in terms of pain resolution. The duration of pain mitigation continued long after the action of the effects of BTX-A injection dissipated, attesting to the importance of “breaking the pain cycle” for long-term control with BTX-A. The color in Figure 1, indicates whether subjects are male (red) or female (blue). The small sample size and variability in dose between patients makes it difficult to draw conclusions. However, there is a marked and consistent trend in pain reduction in each subject after injection.

Fig. 1

LITERATURE REVIEW:

Temporomandibular disorders (TMD) encompass a spectrum of conditions affecting the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) and masticatory muscles, ranking as the second most prevalent musculoskeletal disorders causing pain and functional limitations [1]. Individuals with TMD may report pain in the TMJ area, discomfort during jaw movement, challenges in chewing and speaking, and persistent headaches or earaches resulting from pain radiation.2 Furthermore, enduring pain and discomfort in the masticatory system can significantly impact oral-health-related quality of life.3 Currently, there is a lack of adequate data to conclusively evaluate the favorable outcomes of BTA in myofascial pain syndromes.3

Diagnostic criteria (DC/TMD Classification involve factors such as restricted jaw mobility, issues related to clicking sounds or TMJ locking, and discomfort exacerbated by jaw function.1 Common symptoms associated with TMD include pain in the jaw, face, neck, or shoulders, restricted jaw movement, clicking or popping sounds, masticatory muscle fatigue, headaches, and ear-related symptoms such as pain or ringing.2 TMD are recognized to have a multifaceted origin, often linked to factors such as masticatory muscle hyperfunction, oral parafunction or bruxism (teeth grinding), trauma, hormonal influences, and changes within the joint.4 Occlusion, occlusal factors, and occlusal disharmonies appear to have no causal relationship with TMD except in extreme cases.5,6

Approximately 50% of reported TMD cases involve masticatory myalgia or painful conditions affecting the masticatory muscles.7 Masticatory myofascial (muscle) pain arises within the masticatory muscles, encompassing tendons and fascia, and is identified through tenderness upon palpation of these muscles.8 Patients with myofascial pain in their frontalis or cervical muscles may also encounter headaches or cervical pain.9 Headaches stand out as a common symptom among individuals with TMD. Ballegaard et al.10 found that TMD prevalence among headache patients was 56.1%, with approximately 46.9% of these TMD cases being attributed to myofascial pain. This suggests that those with both headaches and TMD often share several symptoms and diagnostic indicators.9-11

Since its initial approval by the US Food and Drug Administration in 1989 for the treatment of strabismus and blepharospasm, BTX-A has gained approval for addressing hemifacial spasm, cervical dystonia, hyperhidrosis, and cosmetic purposes.12,13 The utilization of BTX-A as an adjunctive therapy for head and neck pain, including tension-type headaches and migraine headaches, is on the rise.13 Botulinum neurotoxins operate by impeding the release of presynaptic acetylcholine at the neuromuscular junction, leading to diminished muscle contraction.14 Notably, BTX-A exhibits antinociceptive properties, exerting its primary effect through the inhibition of neurotransmitters (such as acetylcholine), neuropeptides and inflammatory mediator release.15 Given its ability to reduce muscle activity and alleviate pain, BTX-A is increasingly utilized in managing muscle-related conditions linked to TMD, including spasms and myofascial pain.16 Recent clinical reviews have substantiated the favorable outcomes of BTX-A in these applications.17-19

According to the American Academy of Neurology, supported by high-quality controlled clinical trials, the injection of BTX-A into TMD patients with myogenous pain was likely effective, with level B evidence.20 Updated guidelines from the American Academy of Neurology in 2016 emphasized the potential of BTX-A to increase headache-free days, particularly in chronic migraine management (level A evidence), and reduce the impact of headaches on health-related quality of life (level B evidence).21 Moreover, BTX-A has demonstrated significant efficacy in alleviating pain associated with various conditions beyond migraine headaches.22

The variability in findings underscores the necessity for further RCTs to comprehensively evaluate BTA’s effectiveness as a treatment approach for TMD patients experiencing muscle pain and headaches. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study published in 2023 looking at evaluating TMD and headaches simultaneously concluded that treatment with BTX-A was relatively effective for masticatory myofascial (muscle) pain caused by TMD and headache compared to the saline placebo.33 However, the sample size of this study was small (21 patients), patients experienced general headaches without classifying their headaches into detailed diagnosis such as migraine or tension-type headaches. A randomized, single-center clinical trial consisting of three groups: BTX-A (n=20), saline group (n=19) and lidocaine group (n=19) found a significant reduction in pain in localized myalgia and myofascial pain than in referred remote pain, which persisted up to 6 months.34 Therefore, it is reasonable to conclude that the saline and lidocaine groups are therapeutic interventions rather than true placebo which confounds these studies. CADTH Rapid Response reports, now renamed to Health Technology Review, answer decision-makers’ specific questions regarding health technologies. None of the included CADTH systematic reviews expressed confidence in the efficacy of botulinum toxin for treating TMD.35

CONCLUSIONS

This narrative review is intended to provide short and concise summary of current (within the past five years) evidence to clinicians who are interested in adding on BTX-A as an adjunctive therapy to treating their TMD-related myofascial pain patients. There is growing evidence to support the use of Botox therapy to manage TMD-related pain patients diagnosed with myofascial pain. However, it appears that the discrepancy between studies in determining the long-term benefits of BTX-A injection into masticatory muscles are due to small sample size, shorter follow-up period, and exclusion and inclusion criteria.

With respect to the placebo-controlled trials, the likelihood that they did not reach significance is because saline injections (as well as dry needling) both have an effectiveness rate close to 40% – in other words they are also therapeutic interventions rather than true placebo which confounds these studies.

FUTURE RESEARCH

To strengthen the level of evidence, it is necessary to conduct high quality RCTs looking at the use of Botox in management of TMD-related pain, and headaches, and potentially classifying the presence of a headache diagnoses according to the criteria of the Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society. There needs to be a standardized way to diagnose TMD such as the DC/TMD criteria, and more stringent exclusion and inclusion criteria, minimal bias, and considering heterogeneity between patient subgroups. This approach will ultimately allow for a more optimized evaluation of BTX-A’s clinical effects on TMD.

Oral Health welcomes this original article.

Acknowledgement: We would like to thank Dr. Florian Maire at the Faculty of Arts and Science – Department of Mathematics and Statistics at Universite de Montreal for helping in data interpretation and the construction of Figure 1.

References:

- Schiffman, E.; Ohrbach, R.; Truelove, E.; Look, J.; Anderson, G.; Goulet, J.-P.; List, T.; Svensson, P.; Gonzalez, Y.; Lobbezoo, F.; et al. Diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders (DC/TMD) for clinical and research applications: Recommendations of the International RDC/TMD Consortium Network and Orofacial Pain Special Interest Group. J. Oral. Facial Pain Headache 2014, 28, 6–27.

- Sunil Dutt, C.; Ramnani, P.; Thakur, D.; Pandit, M. Botulinum toxin in the treatment of muscle specific Oro-facial pain: A literature review. J. Maxillofac. Oral. Surg. 2015, 14, 171–175.

- Mor, N.; Tang, C.; Blitzer, A. Temporomandibular myofacial pain treated with botulinum toxin injection. Toxins 2015, 7, 2791–2800.

- Steinkeler, A. Epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment of temporomandibular disorders. Dent. Clin. 2013, 57, 465–479.

- Thomas DC, Singer SR, Markman S. Temporomandibular Disorders and Dental Occlusion: What Do We Know so Far? Dent Clin North Am. 2023 Apr;67(2):299-308.

- Kalladka M, Young A, Thomas D, Heir GM, Quek SYP, Khan J. The relation of temporomandibular disorders and dental occlusion: a narrative review. Quintessence Int. 2022 Apr 5;53(5):450-459.

- Herb, K.; Cho, S.; Stiles, M.A. Temporomandibular joint pain and dysfunction. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2006, 10, 408–414.

- Wieckiewicz, M.; Zietek, M.; Smardz, J.; Zenczak-Wieckiewicz, D.; Grychowska, N. Mental status as a common factor for masticatory muscle pain: A systematic review. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 646.

- Sidebottom, A.J.; Patel, A.A.; Amin, J. Botulinum injection for the management of myofascial pain in the masticatory muscles. A prospective outcome study. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2013, 51, 199–205.

- Ballegaard, V.; Thede-Schmidt-Hansen, P.; Svensson, P.; Jensen, R. Are headache and temporomandibular disorders related? A blinded study. Cephalalgia 2008, 28, 832–841.

- Glaros, A.; Urban, D.; Locke, J. Headache and temporomandibular disorders: Evidence for diagnostic and behavioural overlap. Cephalalgia 2007, 27, 542–549.

- Coté, T.R.; Mohan, A.K.; Polder, J.A.; Walton, M.K.; Braun, M.M. Botulinum toxin type A injections: Adverse events reported to the US Food and Drug Administration in therapeutic and cosmetic cases. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2005, 53, 407–415.

- Song, P.; Schwartz, J.; Blitzer, A. The emerging role of botulinum toxin in the treatment of temporomandibular disorders. Oral Dis. 2007, 13, 253–260.

- Mense, S. Neurobiological basis for the use of botulinum toxin in pain therapy. J. Neurol. 2004, 251, i1–i7.

- Aoki, K.R. Evidence for antinociceptive activity of botulinum toxin type A in pain management. Headache 2003, 43, 9–15.

- Delcanho, R.; Val, M.; Guarda Nardini, L.; Manfredini, D. Botulinum Toxin for Treating Temporomandibular Disorders: What is the Evidence? J. Oral Facial Pain Headache 2022, 36, 6–20.

- De la Torre Canales, G.; Alvarez-Pinzon, N.; Muñoz-Lora, V.R.M.; Vieira Peroni, L.; Farias Gomes, A.; Sánchez-Ayala, A.; Haiter-Neto, F.; Manfredini, D.; Rizzatti-Barbosa, C.M. Efficacy and safety of botulinum toxin type A on persistent myofascial pain: A randomized clinical trial. Toxins 2020, 12, 395.

- De Carli, B.M.G.; Magro, A.K.D.; Souza-Silva, B.N.; de Souza Matos, F.; De Carli, J.P.; Paranhos, L.R.; Magro, E.D. The effect of laser and botulinum toxin in the treatment of myofascial pain and mouth opening: A randomized clinical trial. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2016, 159, 120–123.

- Kütük, S.G.; Özkan, Y.; Kütük, M.; Özdaş, T. Comparison of the efficacies of dry needling and botox methods in the treatment of myofascial pain syndrome affecting the temporomandibular joint. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2019, 30, 1556–1559.

- Muñoz Lora, V.; Del Bel Cury, A.; Jabbari, B.; Lacković, Z. Botulinum toxin type A in dental medicine. J. Dent. Res. 2019, 98, 1450–1457.

- Govindarajan, R.; Shepard, K.M.; Moschonas, C.; Chen, J.J. Botulinum neurotoxin for the treatment of blepharospasm, cervical dystonia, adult spasticity, and headache: Payment policy perspectives. Neurol. Clin. Pract. 2016, 6, 281–286.

- Dodick, D.W.; Turkel, C.C.; DeGryse, R.E.; Aurora, S.K.; Silberstein, S.D.; Lipton, R.B.; Diener, H.C.; Brin, M.F. OnabotulinumtoxinA for treatment of chronic migraine: Pooled results from the double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phases of the PREEMPT clinical program. Headache 2010, 50, 921–936.

- Nixdorf, D.R.; Heo, G.; Major, P.W. Randomized controlled trial of botulinum toxin A for chronic myogenous orofacial pain. Pain 2002, 99, 465–473.

- Ernberg, M.; Hedenberg-Magnusson, B.; List, T.; Svensson, P. Efficacy of botulinum toxin type A for treatment of persistent myofascial TMD pain: A randomized, controlled, double-blind multicenter study. Pain 2011, 152, 1988–1996.

- Guarda-Nardini, L.; Manfredini, D.; Salamone, M.; Salmaso, L.; Tonello, S.; Ferronato, G. Efficacy of botulinum toxin in treating myofascial pain in bruxers: A controlled placebo pilot study. Cranio 2008, 26, 126–135.

- Rollnik, J.D.; Tanneberger, O.; Schubert, M.; Schneider, U.; Dengler, R. Treatment of tension-type headache with botulinum toxin type A: A double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Headache 2000, 40, 300–305.

- Schulte-Mattler, W.J.; Krack, P.; Group, B.S. Treatment of chronic tension-type headache with botulinum toxin A: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter study. Pain 2004, 109, 110–114.

- Jackson, J.L.; Kuriyama, A.; Hayashino, Y. Botulinum toxin A for prophylactic treatment of migraine and tension headaches in adults: A meta-analysis. JAMA 2012, 307, 1736–1745.

- Linde, M.; Hagen, K.; Salvesen, Ø.; Gravdahl, G.B.; Helde, G.; Stovner, L.J. Onabotulinum toxin A treatment of cervicogenic headache: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover study. Cephalalgia 2011, 31, 797–807.

- Freund B, Rao A. Efficacy of Botulinum Toxin in Tension-Type Headaches: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Pain Pract. 2019 Jun;19(5):541-551.

- Thambar S, Kulkarni S, Armstrong S, Nikolarakos D. Botulinum toxin in the management of temporomandibular disorders: a systematic review. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2020 Jun;58(5):508-519.

- de-la-Hoz, J.L.; de-Pedro, M.; Martín-Fontelles, I.; Mesa-Jimenez, J.; Chivato, T.; Bagües, A. Efficacy of botulinum toxin type A in the management of masticatory myofascial pain: A retrospective clinical study. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2022, 153, 683–691.

- Kim SR, Chang M, Kim AH, Kim ST. Effect of Botulinum Toxin on Masticatory Muscle Pain in Patients with Temporomandibular Disorders: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Pilot Study. Toxins (Basel). 2023 Oct 4;15(10):597.

- Montes-Carmona JF, Gonzalez-Perez LM, Infante-Cossio P. Treatment of Localized and Referred Masticatory Myofascial Pain with Botulinum Toxin Injection. Toxins (Basel). 2020 Dec 23;13(1):6.

- la Fleur P, Adams A. Botulinum Toxin for Temporomandibular Disorders: A Review of Clinical Effectiveness, Cost-Effectiveness, and Guidelines [Internet]. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; 2020 Feb 25. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK562946/

About the Authors:

Dr. Sherif Elsaraj attained his dental degree and a master’s in Oral Biology from the University of Manitoba. He furthered his education by earning a Ph.D. in Craniofacial Pain and Health Sciences from McGill University. Currently he supervises General Residency Program residents at the Jewish General Hospital’s clinic in TMD and orofacial pain.

Dr. Brian Freund received his medical degree from McMaster University and received his dental and specialist training at the University of Toronto. He practices as an Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeon at the Chrysalis Dental Centre in Toronto with special interests in immediately loaded implant rehabilitation, neuromuscular dysfunction, and minimally invasive facial rejuvenation.

Dr. Ahmed Almuzayyen obtained his dental degree from the University of Dammam, followed by a Master of Science in Dental Oncology at SUNY Buffalo. Subsequently, he completed an Oral Maxillofacial surgery residency and earned a Master’s degree at the University of Manitoba. Currently, he serves as an Orthognathic and TMJ surgery fellow at Dalhousie University. Associate consultant of Oral&Maxillofacial surgery King Fahad Specialist Hospital, Dammam/ Saudi Arabia.