Abstract

Extraction of first premolars is usually the chosen treatment for Class I severe crowding/protrusion. However, the treatment will be complicated if premolars are with Dens Evaginatus (DE), called Leong premolar, and unilateral scissors bite is present. In this case of an adolescent, the two maxillary second premolars and the mandibular left second premolar and right first premolar were selected for extraction because their prominent DE and the mandibular right second premolar had been worn down without any symptoms. One orthodontic mini-screw was inserted to assist in correcting the unilateral scissors bite. The total duration of treatment was 26 months.

Result: The excessive protrusion of upper incisors was reduced significantly, severe crowding in both arches was eliminated, unilateral scissors bite was corrected, and Class I molar relationship on both sides was established.

Conclusion: It was reasonable to have extracted the premolars with prominent DE to minimize the risk of pulpal inflammation resulting from attrition or fracture of DE. Orthodontic mini-screws could be used to treat scissors bites more quickly.

There are two major reasons to extract teeth in orthodontics: 1) to provide space to align the remaining teeth in severe crowding and 2) to allow incisors to be retracted so protrusion can be reduced.1 Extraction of first premolars is usually the treatment of choice for Class I crowding/protrusion.1 However, treatment planning will be challenging if DE is affecting the second premolars.

DE is a developmental anomaly and primarily affects premolar teeth, characterized by a globe-shaped projection of enamel in the region of the central groove.2 Because this extra cusp contains a pulp horn, attrition or fracture can result in pulp exposure, leading to pulpal inflammation and its sequelae.2 A study reported that the prevalence of DE among Taiwanese students was 4.08%, compared to 0% in the Spanish Caucasian group,3 although another research reported that the prevalence of DE is 6.2% in the permanent dentition in white orthodontic patients.4

Scissors bite, also called Brodie bite or Brodie Syndrome,5 is a type of transverse malocclusion in which the maxillary posterior teeth occlude completely buccal to the mandibular posterior teeth. The prevalence rates of scissors bite were 1- 2% in mixed dentition6,7 and 5% in permanent dentition.7

A scissors bite is generally treated through inter-maxillary tractions. Some clinical studies report it is more efficient and quicker to correct scissors bite with temporary anchorage devices (TADs) like orthodontic mini-screws.8,9 Orthognathic surgery is a necessary complement to treat severe skeletal scissors bite besides general treatment.10,11 Here we have reported successful treatment of an adolescent case who has severe protrusion of maxillary incisors, bimaxillary crowding, Leong premolars, and a unilateral scissors bite.

Diagnosis and Etiology

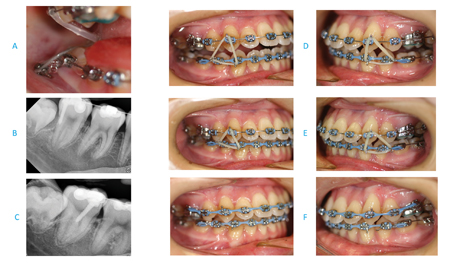

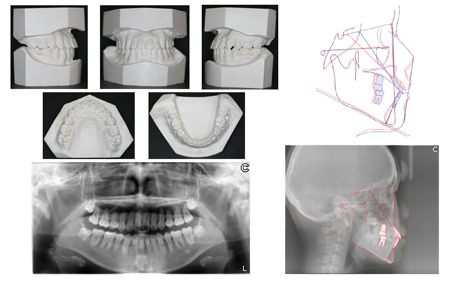

A 13-year-old and 8-month-old girl presented with the chief complaint of excessive protrusion of upper anterior teeth. Her medical and dental histories were non-contributory. She had a slightly convex profile with incompetent lips but a symmetric face. The intraoral examination showed the excessive protrusion of maxillary central incisors, severe bimaxillary crowding, prominent DE of the two upper second premolars and lower left second premolar, wearing of the DE of the mandibular right second premolar without any signs and symptoms, a unilateral scissors-bite on the right, a Class I molar relationship on the left, a Class III molar relationship on the right, maxillary dental midline shift to the left by 2.0 mm, mandibular dental midline shift to the right by 3.0 mm (Fig. 1). On dental cast analysis, overbite was 0.5 mm, and overjet was 5.0 mm; deficiency of space in the maxillary and mandibular arches was 13.0 mm and 10.0 mm, respectively; mandibular right second molar inclined lingually forming unilateral scissors bite; the mesiodistal widths of the maxillary first premolars were 8.0 mm each, and the second premolars 7.0 mm each. The mesiodistal widths of the four mandibular premolars were all 7.5 mm each (Fig. 2). Pre-treatment cephalometric analysis showed a Class I skeletal relationship, but excessive protrusion of upper incisors and anteriorly downward rotation of the mandible contributed to an open bite with U1/SN 122.2°, U1—NA 11.4 mm, SN/MP 40.5°and PP/MP 34.4° (Table 1). Pre-treatment panoramic radiographs showed crowding and tipping in arches and four developing wisdom teeth (Fig. 2). No temporomandibular disorder (TMD) symptoms or signs were reported or found clinically.

Fig. 1

Fig. 2

Table 1: Cephalometric Summary

| Ceph Name | Pretreatment | Posttreatment | Norm | Unit |

| SNA | 79.3 | 79.1 | 82±3 | ° |

| SNB | 78.8 | 78.4 | 80±3 | ° |

| ANB | 0.6 | 0.7 | 2±2 | ° |

| SN/MP | 40.5 | 40.4 | 32.9±5.2 | ° |

| FH/MP | 30.8 | 30.0 | 25.1±4.5 | ° |

| SN/PP | 6.1 | 5.7 | 8.5±3 | ° |

| PP/MP | 34.4 | 34.7 | 23.5±5 | ° |

| U1/L1 | 113.7 | 122.0 | 130±10 | ° |

| U1/SN | 122.2 | 111.1 | 102±6 | ° |

| L1/MP | 83.6 | 86.5 | 94±4.5 | ° |

| U1-NA | 11.4 | 7.9 | 4.3±2.7 | mm |

| L1-NB | 5.1 | 5.8 | 4±1.8 | mm |

| UL-EL | 2.1 | 1.6 | -2±2 | mm |

| LL -EL | 1.8 | 2.7 | -2.8±2 | mm |

DE is an odonto¬genic developmental anomaly. The etiology of this girl’s unilateral scissors bite may be due to the lingual ectopic eruption of the mandibular right second molar.

Treatment Objectives

The treatment objectives were to reduce the excessive upper anterior tooth protrusion, to solve severe crowding and dental midline shift in both arches, to eliminate unilateral scissors bite with no further downward rotation of the mandible, to establish Class I molar and canine relationship, and to fulfill final alignment and intercuspation relationship.

Treatment Alternatives

The first alternative was to extract four first premolars. This option facilitated the control of posterior anchorage to retract anterior teeth and solve crowding. The disadvantage of this alternative was that the two upper second premolars and the lower left second premolar with significant DE would be kept. The possible risk of DE fracture or wear would be predictable. The second alternative was to extract the four-second premolars. This would reduce the potential of pulpal inflammation resulting from attrition or fracture of the DE but would require more control over the posterior anchorage. The upper second premolars were narrower than the first, so less space would be acquired, negatively influencing the treatment outcome. The third alternative was like the second except that the mandibular right first premolar would be extracted instead of the second premolar, whose DE had been worn down without any symptom, which was favourable to the formation of Class I molar relationship on the right and the elimination of crowding in the mandibular arch.

The patient and her parents chose the third alternative and agreed to have the upper anterior and first premolars reduced inter-proximally to obtain more space. They also concurred with our suggestion of applying an orthodontic mini-screw to help correct the unilateral scissors bite.

Treatment Progress

The two maxillary second premolars and the mandibular left second premolar and right first premolar were extracted. One week later, 0.022” slot brackets of the Roth prescription (Ortho Technology, West Columbia, SC) were bonded on anterior teeth and remaining premolars in both arches. Two bands with soldered palatal arch were cemented on the two maxillary first molars. The initial archwires were 0.012” nickel-titanium, then 0.014” and 0.016” nickel-titanium archwires before using stainless steel archwires. Open coil springs (0.010 x 0.030”) were used to push back the two maxillary first premolars and the mandibular right canine to occupy most of the space left by the extracted teeth. The levelling and alignment were almost achieved after seven months. Unfortunately, the treatment had been interrupted for four months because of the Covid-19 pandemic.

The treatment re-started with a removable mandibular bite plate to open occlusion to correct the right scissors bite. The bite plate was retained with ball clasps. A lingual button was bonded on the mandibular right second molar. A 5/16” elastic was placed for cross-traction. Two months later, one buccal tube was bonded onto the mandibular right second molar. A 0.016” stainless steel archwire was placed in the lower arch, and under local anesthesia, one 1.4 mm x 8.0 mm orthodontic mini-screw (made in Korea, Rocky Mountain Orthodontics, USA) was inserted around 5.0 mm buccal to the cementoenamel junction of the mandibular right second molar. An energy chain (100 g. Rocky Mountain Orthodontics, USA) was placed from the mini-screw to the lingual button and changed once a month (Fig. 3). The unilateral scissors bite was corrected three months later, and the TAD was removed under local anesthesia. The maxillary soldered palatal arch was cut and removed. The mandibular second molar formed a premature occlusion with its opposite maxillary molars. Vertical traction started on both sides with ¼” elastic. The mandibular bite plate was trimmed down gradually at each appointment until its utilization after three months. The archwires were changed to 0.016” x 0.022” stainless steel and power chains (Ortho Technology, USA) were used to close the remaining spaces in both arches with continuous vertical traction for two months. The maxillary anterior teeth and two first premolars were trimmed interproximally to create 1.0-1.5 mm space for reducing maxillary anterior protrusion. The archwires were replaced by 0.017” x 0.025” stainless steel, and power chains and vertical traction were continued for two months (Fig. 3). One more month later, braces were removed, and Essix retainers were worn all day except for meals for the first six months, then worn only at night. The total duration of treatment was 26 months. The patient and her parents were delighted with the treatment outcome.

Fig. 3

Treatment Results

The patient’s profile was improved greatly, excessive protrusion of upper incisors was reduced significantly, severe crowding in both arches was eliminated, unilateral scissors bite was resolved, and dental midline shift in both arches was mostly corrected; class I molar relationship on both sides, and Class I canine relationship on the right side was established with a slight Class II canine relationship on the left side (Fig. 4). Normal over-bite and over-jet were established. A post-treatment cephalometric radiograph showed that neither further mandibular clockwise rotation nor anterior open bite was displayed, but maxillary incisors were retracted recognizably. A post-treatment panoramic radiograph showed good axial inclinations of all teeth (Fig. 5) (Table 1). The superimposed tracings showed that the growth and development of the mandible were directed downward and forward, and excessive maxillary incisor protrusion was diminished obviously (Fig. 5). No TMD symptoms or signs were reported or found clinically after treatment. The treatment result was stable at the 6-month follow-up (Fig. 6).

Fig. 4

Fig. 5

Fig. 6

Discussion

Treatment options for DE include intermittent grinding of DE before any pulpal involvement, DE protection with composite resin, coronal pulpotomy, apexification combined with root canal filling, root canal therapy in teeth with mature roots, apical surgery, and extraction in cases of orthodontic treatment.12 If premolar extractions are planned because of arch length inadequacy, every effort should be made to prevent extraction of a “normal” tooth if a Leong premolar can be extracted instead.13 In our case, severe crowding in bimaxillary arches and excessive upper anterior protrusion concurred with Leong premolars. Premolar extractions were planned in our treatment plan. The DE of the two upper second premolars and the lower left second premolars was more significant than their adjacent first premolars’. However, the crown mesiodistal widths of the maxillary first premolars were more prominent than the second premolars. The DE of the mandibular right second premolar has been worn down without any symptoms or signs. We extracted the two maxillary second premolars and the mandibular left second premolar and right first premolar to reduce the potential of pulpal inflammation resulting from attrition or fracture of prominent DE. We applied palatal arch and open coil springs to push back the two maxillary first premolars and the mandibular right canine to control bimaxillary posterior anchorage. Interproximal reduction of the maxillary anterior teeth and first premolars created 1.0-1.5 mm space to help reduce maxillary anterior protrusion.

The etiology of the scissors bite is complicated. It may be due to the ectopic eruption of the maxillary molar significantly buccal to the mandibular or from deformity of maxillofacial skeletal growth and development and /or dysfunction of maxillofacial musculature. Scissors bite may only involve a single maxillary posterior tooth with its opposing mandibular teeth or multiple upper and lower posterior teeth on one or both sides. Clinical studies report the more efficient and quick procedure of correcting the scissors bite with the assistance of orthodontic mini-screws.8,9 Still, there was the possibility that the root of the seriously lingual inclined mandibular right second molar was damaged in our case, so elastic cross-traction was applied for two months before inserting one orthodontic mini-screw. Potential complications of root injury include loss of tooth vitality, osteosclerosis, and dentoalveolar ankyloses. However, trauma to the outer dental root without pulpal involvement will most likely not influence the tooth’s prognosis.14 Change in horizontal X-ray beam angulation in periapical radiographs was made to confirm the mini-screw did not touch the root of the mandibular right second molar. In our case, the correction of the unilateral scissors bite accelerated with the orthodontic mini-screws assistance.

After eliminating the unilateral scissors bite, the mandibular second molar formed a premature occlusion with the two opposite maxillary molars. Vertical traction was used to close the open bite, but no further mandibular clockwise rotation happened after treatment. Occlusal forces and further facial growth and development of the adolescent patient should be accounted for.

Conclusion

The premolars with prominent DE were extracted to provide space for having successfully resolved severe crowding and protrusion, intending to decrease the potential of pulpal inflammation resulting from attrition or fracture of DE. Unilateral scissors bite could be successfully treated more quickly using an orthodontic mini-screw. No significant clockwise rotation of the mandible occurred in this adolescent patient after vertical traction.

Oral Health welcomes this original article.

References

- Proffit WR, Fields HW and Sarver DM. Orthodontic treatment planning: limitations, controversies, and special problems. Contemporary orthodontics. Fourth edition. Mosby St. Louis 2007. P 276-279.

- Sapp JP, Eversole LR and Wysocki GP. Contemporary oral and maxillofacial pathology. Second edition. 2004. Mosby St. Louis.

- Lin CS, Maria LM, Chirag C S, Mar JS and Benjamín M. Prevalence of premolars with Dens Evaginatus in a Taiwanese and Spanish Population and Related Complications of the Fracture of its Tubercle. EUR Endod J 2018; 2: 118-22 .

- Uslu O, Akcam MO, Evirgen S and Cebecid I. Prevalence of dental anomalies in various malocclusions. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2009;135:328-35.

- Allan G. Brodie. Consideration of musculature in diagnosis, treatment, and retention. International Journal of Orthodontia and Dentistry for Children. 1952Nov. 38 (11):823–835.

- Katri KN, Raija, L, Vuokko, L, Leo, KN, Juha, V. Occurrence of malocclusion and need of orthodontic treatment in early mixed dentition. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2003 Dec: 124(6): 631-8.

- G. Lombardo, FV, P. Negri, SP, C. Barilotti, LP, S. Colombo, MO, S. Cianetti. Worldwide prevalence of malocclusion in the different stages of dentition: a systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Paediatric Dentistry vol. 21/2-2020.

- Jung MH. Treatment of severe scissor bite in a middle-aged adult patient with orthodontic mini-implants. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2011;139:S154-65.

- Lee SA, Chang CCH and Robertsc WE. Severe unilateral scissors-bite with a constricted mandibular arch: Bite turbos and extra-alveolar bone screws in the infrazygomatic crests and mandibular buccal shelf. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2018; 154:554-69.

- Ozkalayci N, Ozer M and Sumer M. Treatment of unilateral buccal crossbite With mandibular symphyseal distraction osteogenesis. Korean J Orthod 2011; 41(1):59-69.

- Badra H, Leeb SY, Parkc HS, Ohed JY, Kange YG and Ahne HW. Camouflage treatment of posterior bite collapse in a patient with skeletal asymmetry by using posterior maxillary segmental osteotomy. Korean J Orthod 2020; 50(4):278-289.

- Chen JW, George T, Huang J and Bakland LK. Dens evaginatus Current treatment options. JADA 2020:151(5):358-367.

- McCulloch KJ, Mills CM, Greenfeld RS and Coil JM. Dens evaginatus from an orthodontic perspective: Report of several clinical cases and review of the literature. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop 1997; 112; 670- 5.

- Kravitza ND and Kusnotob B. Risks and complications of orthodontic miniscrews. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2007;131:00.

About the Author

Dr. Wenyong Liang received his DMD in 1988 and MDS (Master of Dental Science in Orthodontics) in 1993 from West China College of Stomatology, Sichuan University, China. He completed the Tweed Study Course at the Charles H. Tweed International Foundation for Orthodontic Research & Education in 1997. Dr. Liang studied at the University of Washington as a visiting scholar from 1999-2000. Dr. Liang received his DDS in 2005 from Western University, Schulich School of Medicine and Dentistry, Canada. He is now practising in Toronto, Canada.