Transverse facial growth is the first dimension to complete in the growing adolescent and is often overlooked by clinicians in the absence of a posterior crossbite.1,2 Early diagnosis and treatment is critical for prevention of more invasive treatment modalities such as orthognathic surgery. However, interceptive treatment may not always be feasible as an increasing number of patients first present for orthodontic treatment in their late teens or adult years.2

IMPORTANCE OF THE TRANSVERSE DIMENSION

Management of the transverse dimension is an essential treatment objective in orthodontics. The goal is to achieve ideal arch coordination and an ideal functional outcome.3 Proper transverse coordination of the maxilla and mandible allows for ideal interdigitation of the dentition, avoidance of interferences which can lead to functional shifts and/or reduced overbite, and contributes to an aesthetically pleasing smile with the elimination of dark buccal corridors. In growing patients, clinicians can consider use of orthopedic appliances such as the rapid palatal expander (RPE) to correct maxillary transverse deficiencies (MTDs) when warranted.4 However, in non-growing, skeletally mature patients, ossification of the mid-palatal suture makes orthopedic expansion difficult. Clinicians are then left to decide whether a transverse problem can be managed orthodontically or will require surgical intervention. This decision can be challenging because there are many diagnostic factors to consider.

The purpose of this article is to: 1) present some of the management options for MTDs in non-growing patients, 2) discuss key clinical indicators which drive decision making, 3) introduce an online Surgical Expansion Calculator created by the authors that can assist clinicians when treatment planning cases presenting with transverse deficiencies, and 4) present a case study demonstrating clinical application of the calculator.

MANAGEMENT OPTIONS

In non-growing patients with a mild MTD, it is important to first determine if the etiology is skeletal or dental in nature. If the malocclusion presents primarily with dental tipping (i.e, palatal tipping of the maxillary posterior teeth or buccal tipping of the mandibular posterior teeth), transverse discrepancies can often be managed orthodontically since these compensations are indicative of a dental etiology. Orthodontic expansion can be achieved by increasing the buccal crown torque of the maxillary posterior teeth and/or decreasing the buccal crown torque of the mandibular posterior teeth.5 In essence, mild alterations in the buccolingual inclinations of the maxillary and mandibular buccal segments allow for camouflage of the MTD. Specific techniques that can be implemented include torque expression via careful archwire selection, archwire expansion, transpalatal arches, quad helices, aligner tooth movements, and the use of intermaxillary cross-arch elastics.2 This is the simplest and most efficient solution when indicated, obviating the need for more invasive surgical procedures.

When a MTD is severe and skeletal in nature, that is beyond the limits of dental camouflage, surgical procedures are needed in addition to orthodontics to achieve transverse correction. These malocclusions tend to present with dental compensations involving buccal tipping of the maxillary posterior teeth and lingual tipping of the mandibular posterior teeth in the absence or presence of a posterior crossbite.5 Attempting to correct these malocclusions via orthodontic expansion may lead to excessive buccal flaring and extrusion of the dentition or require tooth movement beyond the alveolar housing which increases the risk of root resorption, relapse, and negative periodontal consequences.6,7 Surgical correction addresses the true skeletal etiology of the malocclusion while minimizing these undesirable side effects.2 The clinician is left to decide between two surgical options: segmental Le Fort I osteotomy (SLF) or surgically assisted rapid palatal expansion (SARPE). Deciding between the two procedures does not solely depend on the magnitude of the transverse discrepancy, as they have their own unique indications. In general, a SARPE is indicated for: expansions greater than 7mm, cases where no other surgery is required (i.e. no antero-posterior (AP) discrepancies or vertical discrepancies), V-shaped palates, excess buccal corridor display, previously failed rapid palatal expansion, tooth size-arch length discrepancies (TSALD), and prior to large LF1 advancements that require greater than 5mm of expansion.3,8,9 SLF is indicated for: absolute transverse discrepancies less than 7mm, and when there is a coexisting AP, vertical, or asymmetry correction that warrants multiple surgical movements.3,9

The SARPE procedure is the mainstay intervention to address significant maxillary transverse discrepancies in the skeletally mature patient.8,10,11 The technique employs an orthopedic appliance placed on the palate following strategic surgical osteotomies, which overcome the resistance of ossified articulations and sutures adjoined to the maxillary bone. The appliance utilizes the principles of distraction osteogenesis by providing daily intermittent expansion (0.5mm per day) to achieve rapid maxillary distraction of the two maxillary halves within several weeks.12 Expansions of up to 15-20mm can be obtained. If a SARPE is indicated, the next decision involves the mechanical apparatus to create the distraction; surgeons have options of tooth-borne, bone-borne, hybrid, or a combination of these devices (Table 1). A previous study has demonstrated no significant differences in outcomes between the different types of distraction appliances used13 so that the decision of the mechanical choice is purely surgeon specific.

Table 1: Distraction devices that can be used when performing SARPE.

| Type of Distraction Appliance | Example | Remarks |

| Bone-Borne (Figure 1) | TAD Retained Acrylic Palatal Expander (TRAPE), Transpalatal Distractor | Pure boney expansion, Up to 20mm expansion, requires second procedure to remove |

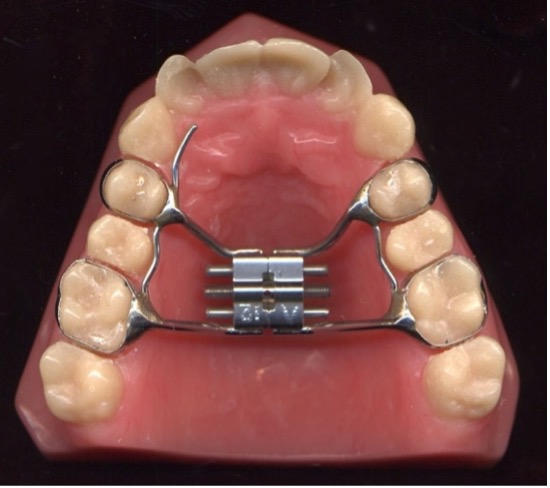

| Tooth-Borne (Figure 2) | Hyrax appliance, Bonded RPE | Some dental expansion (tipping), Up to 10-15mm expansion |

| Bone and Tooth Borne (Figure 3) | Hass appliance | Difficult hygiene, not suitable for longer retention periods |

| Screw-retained (Figure 4) | Miniscrew Assisted RPE (MARPE) | Limited expansion ability |

Fig. 1

Fig. 2

Fig. 3

Fig. 4

The decision to perform a SARPE over a SLF remains an area of controversy. The main challenge is how to best mitigate against the well know instability of widening the maxilla.14 Overall relapse rates15-18 in general appear to be: in the canine region: 9-30% ; in the molar region: 8-55%. Kraut19 had shown that surgical expansion was more stable than non-surgical and was the first to express a consideration to overexpand the segments by 1-1.5 mm to compensate for relapse. Pogrel15 in an early study reported relapse rates of 0.88 +/- 0.48 mm and these where greatest in the canine region, followed by the molar region and then the premolar region. Finally, there has been evidence to support the use of a TAD-retained maxillary expansion device without osteotomies (MARPE)20 to expand a narrow maxilla in the adult. However, the long-term stability and predictability has not been clearly demonstrated.21

DETERMINING THE MAGNITUDE OF THE TRANSVERSE DISCREPANCY

Determining when a transverse deficiency is mild, moderate, or severe and therefore amenable to orthodontic, SLF, or SARPE is a somewhat challenging decision to make as there are multiple clinical findings that need to be considered when assessing the true transverse discrepancy between the maxilla and mandible. Four elements that should be given consideration when assessing the magnitude of the MTD include the: 1) transverse measurement, 2) lingual inclination of maxillary buccal segments, 3) curve of Wilson, and 4) TSALD (Table 2)9

The first factor to consider is the most intuitive—the absolute transverse measurement of the discrepancy. The authors recommend making the measurements between central fossae of the upper maxillary first molars, and distobuccal cusps of the mandibular first molars. Comparing these measurements gives a baseline measurement but does not consider the magnitude of dental compensations involved in the malocclusion.

Table 2: Factors to consider when assessing the maxillary transverse discrepancy.

| Factor No. | Factor | Remarks |

| 1 | Transverse measurement (Figure 5) | An absolute millimeter measurement of the first molar difference of the maxilla and mandible |

| 2 | Inclination of maxillary buccal segments (Figure 6) | Determined as upright, buccally, or lingually inclined segments |

| 3 | Curve of Wilson (Figure 6) | Described as steep, normal, or shallow |

| 4 | TSALD | Is extraction necessary to fit the mandibular arch? |

Fig. 5

Fig. 6

The second and third factors to consider are the inclination of the buccal segments in the maxilla and the curve of Wilson in the mandible. These factors are necessary to consider because such dental compensations can mask the severity of the transverse discrepancy at the skeletal base of the maxilla and mandible. The authors recommend examining the buccolingual inclinations of the buccal segments by examining the dental casts from the posterior. Low-hanging maxillary palatal cusps and excessive show of the mandibular buccal surfaces from the occlusal view are additional helpful indicators of dental compensations of MTDs.

The fourth factor to consider is the TSALD—a less obvious but important element to consider. There may be cases where a typical space analysis of the maxillary arch would call for extractions to resolve a severe TSALD. However, treating such a case non-extraction would cause an increase in the maxillary transverse dimension which may be helpful to address the MTD (if the alveolar housing and periodontal tissues allow it). Conversely, cases with mild crowding or spacing are not as amenable to dental increases in arch width which would direct the decision to manage the case surgically.

Only when these four elements are considered together can clinicians arrive at a synergistic treatment plan best suited for an individual patient. Because there are multiple variables to factor in when diagnosing and treatment planning cases with MTDs, the authors present the following algorithm-based calculator to help simplify the expansion decision.

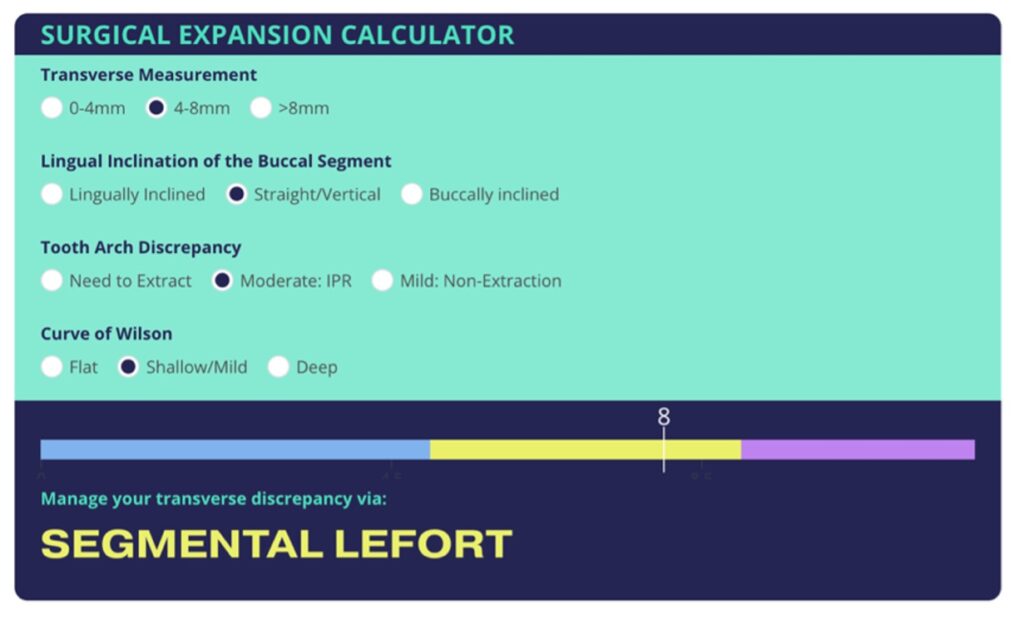

THE SURGICAL EXPANSION CALCULATOR

To assist clinicians in making this diagnosis and therefore generating the most appropriate treatment recommendation, the authors have created an algorithm-based calculator called the Surgical Expansion Calculator (Fig. 7) which factors in all four elements described above (Table 2). To utilize this calculator, clinicians simply analyze the case and select the corresponding option in the calculator. The Surgical Expansion Calculator assigns a score of 1, 2, or 3 (from left to right) for each possible option under the various diagnostic factors. A total score will be automatically calculated and a treatment recommendation generated below. Scores less than 5 can be managed orthodontically, scores of 5-8 can be managed with a segmental Le Fort, and scores over 8 can be managed with SARPE. This calculator may serve as a guide to the clinician, however, it is important to remember that this is only one area of consideration among many when arriving at a comprehensive treatment plan. The calculator can be accessed online at: https://www.orthocalculator.org/surgical-expansion-calculator

Fig. 7

CASE STUDY

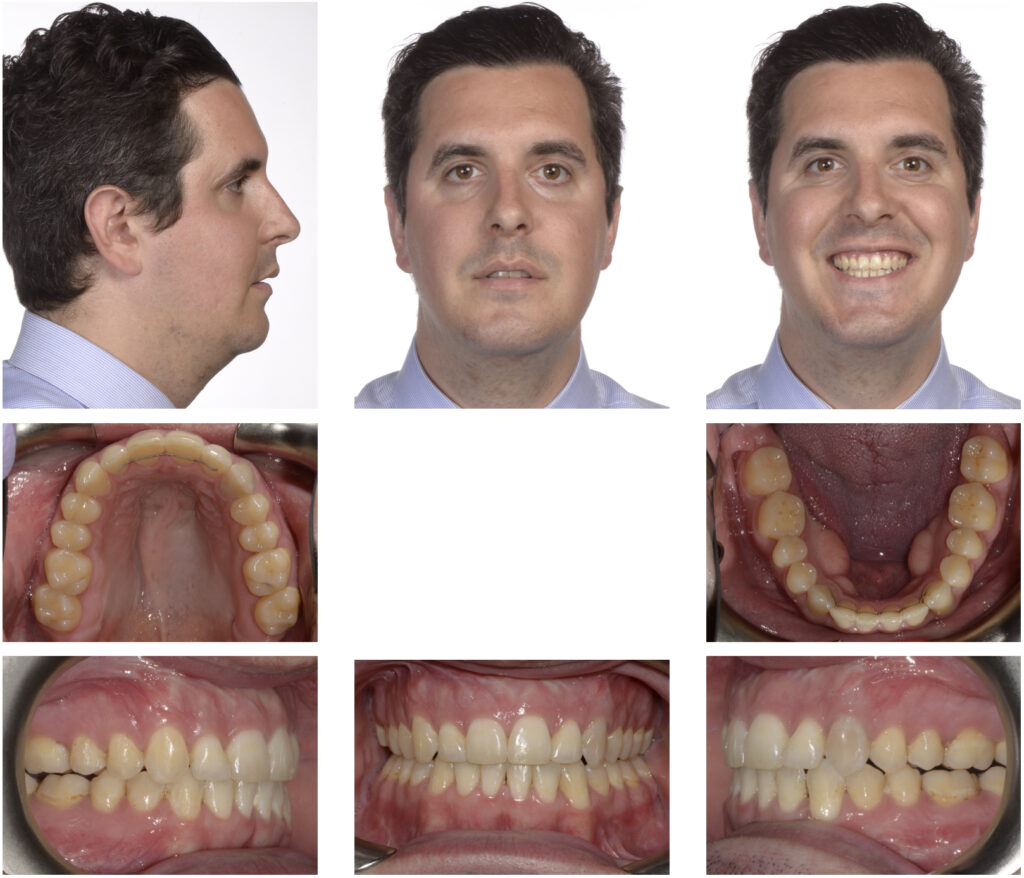

An adult patient presented for comp-rehensive orthodontic treatment (Fig. 8). Upon examination, there was a MTD that would need to be addressed in order to achieve a functional occlusion and a pleasing smile. To determine the most appropriate management option, the Surgical Expansion Calculator was used. This patient was diagnosed as having a severe transverse measurement, straight maxillary buccal segments, a non-extraction arch, and a deep curve of Wilson (Fig. 9).

Fig. 8

Fig. 9

As determined clinically and supported by our calculator, this patient was approached as a surgical-orthodontics case that treated with SARPE and braces (Fig. 10). This management strategy allowed for adequate correction of the MTD and facilitated an ideal orthodontic finish, with a functional occlusion and improved smile aesthetics (Fig. 11).

Fig. 10

Fig. 11

CONCLUSION

Managing the transverse dimension in the orthodontic patient can be easily approached if clinicians understand:

- The variables involved (relative inter-arch difference, inclination of teeth, TSALD, skeletal shape),

- The clinical interventions available both surgical and non-surgical, and

- A method of accumulating the data and interpreting it as demonstrated in our calculator.

By utilizing a few of these strategies, the clinical challenge may be more easily overcome. The benefits of this approach provide the clinician some flexibility in assessing the clinical problem and avoids a dogmatic narrow focused reaction that sometimes obscures our judgements.

Oral Health welcomes this original article.

References

- Chung C-H. Diagnosis of Transverse Problems. Seminars in Orthodontics. 2019;25.

- Reyneke JP, Conley RS. Surgical/Orthodontic Correction of Transverse Maxillary Discrepancies. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2020;32(1):53-69.

- Davenport-Jones L. Preadjusted Edgewise Fixed Orthodontic Appliances: Principles and Practice. Chapter 22: Management of the transverse dimension. First ed2022.

- Petrén S, Bondemark L, Söderfeldt B. A systematic review concerning early orthodontic treatment of unilateral posterior crossbite. Angle Orthod. 2003;73(5):588-96.

- Southard TE, Marshall SD, Allareddy V, Shin K. Adult transverse diagnosis and treatment: A case-based review. Seminars in Orthodontics. 2019;25(1):69-108.

- Langford SR. Root resorption extremes resulting from clinical RME. Am J Orthod. 1982;81(5):371-7.

- Greenbaum KR, Zachrisson BU. The effect of palatal expansion therapy on the periodontal supporting tissues. Am J Orthod. 1982;81(1):12-21.

- Suri L, Taneja P. Surgically assisted rapid palatal expansion: a literature review. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2008;133(2):290-302.

- Caminiti M. Digital Planning in Orthognathic Surgery. In: Retrouvey J-M, Abdallah M-N, editors. 3D Diagnosis and Treatment Planning in Orthodontics: An Atlas for the Clinician. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2021. p. 267-82.

- Koudstaal MJ, Poort LJ, van der Wal KG, Wolvius EB, Prahl-Andersen B, Schulten AJ. Surgically assisted rapid maxillary expansion (SARME): a review of the literature. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;34(7):709-14.

- Graber T. Functional appliances. In: Graber T, Vanarsdall R, Vig K, Huang G, editors. Orthodontics current principles and techniques. St. Louis: Elsevier, Mosby; 2005. p. 515.

- Betts NJ. Surgically Assisted Maxillary Expansion. Atlas Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2016;24(1):67-77.

- Caminiti M, Marko J, Metaxas A. TAD retained Acrylic palatal expander. American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons; Annual Meeting; San FranciscoOct 14, 2017.

- Proffit WR, Turvey TA, Phillips C. Orthognathic surgery: a hierarchy of stability. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 1996;11(3):191-204.

- Pogrel MA, Kaban LB, Vargervik K, Baumrind S. Surgically assisted rapid maxillary expansion in adults. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 1992;7(1):37-41.

- Berger JL, Pangrazio-Kulbersh V, Borgula T, Kaczynski R. Stability of orthopedic and surgically assisted rapid palatal expansion over time. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1998;114(6):638-45.

- Anttila A, Finne K, Keski-Nisula K, Somppi M, Panula K, Peltomäki T. Feasibility and long-term stability of surgically assisted rapid maxillary expansion with lateral osteotomy. Eur J Orthod. 2004;26(4):391-5.

- Koudstaal MJ, Wolvius EB, Schulten AJ, Hop WC, van der Wal KG. Stability, tipping and relapse of bone-borne versus tooth-borne surgically assisted rapid maxillary expansion; a prospective randomized patient trial. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;38(4):308-15.

- Kraut RA. Surgically assisted rapid maxillary expansion by opening the midpalatal suture. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1984;42(10):651-5.

- Choi SH, Shi KK, Cha JY, Park YC, Lee KJ. Nonsurgical miniscrew-assisted rapid maxillary expansion results in acceptable stability in young adults. Angle Orthod. 2016;86(5):713-20.

- Kapetanović A, Theodorou CI, Bergé SJ, Schols J, Xi T. Efficacy of Miniscrew-Assisted Rapid Palatal Expansion (MARPE) in late adolescents and adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Orthod. 2021;43(3):313-23.

- McNamara Jr J. Chapter 12: Maxillary Deficiency Syndrome. In: Mosby, editor. Current therapy in orthodontics. USA. 2010. p. 137-42.

About the Author

Dr. Daniel Richmond recently completed his Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics residency at the University of Toronto. He is completing a fellowship in Craniofacial Orthodontics at the New York University.

Dr. Domenico Barranca completed his DDS at the University of Toronto and a general practice residency at The Hospital for Sick Children. Recently, he completed his orthodontic residency at the University of Toronto.

Dr. Marco Caminiti is an Associate Professor at the University of Toronto. He is the Head and Program Director of the Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Residency Program at the University of Toronto and Head of OMFS at Humber River Hospital.