Abstract

Replacing a missing tooth in the anterior maxilla with an implant-supported crown (ISC) can be challenging. Reduced mesiodistal space can add further complexity to this treatment. A 61-year-old patient was examined with respect to compromised aesthetics and fit of a recently inserted ISC in site 12. Clinical and radiographic examination revealed that the fit and contours of the crown were suboptimal. Prosthetic retreatment involved diagnostic removal of the ISC for assessment, obtaining soft tissue health, insertion of an optimal provisional fixed restoration, achieving patient comfort and satisfaction with aesthetics, and replication of the provisional restoration contours in the new definitive ISC. Treatment of the anterior maxilla with a single implant-supported restoration is technique sensitive, and an error in any step of the treatment can result in aesthetic or technical failure. Accurate impression and provisional restoration are necessary to create a well-fitting aesthetic and functional restoration. In narrow mesio-distal spaces, careful consideration must be given to material selection.

An implant-supported crown (ISC) is a sound treatment approach for a single missing tooth that has numerous advantages (Bragger et al., 2005). However, replacement of a missing tooth in the aesthetic zone with an ISC can be technically challenging due to significant aesthetic and phonetic demands. The restoration must be in harmony with the adjacent and contralateral teeth in size, contour, color, texture, and soft tissue frame (Chang et al., 1999). Optimal three-dimensional implant position is critical for treatment success. Implant malposition within the edentulous space can complicate delivery of prosthodontic care and can compromise aesthetic and biologic outcomes. This case illustrates restorative difficulties that can be posed by a deeply positioned implant within a narrow mesio-distal space of a maxillary lateral incisor.

Case report

Chief complaint and dental history

A 61-year-old female patient was referred to the University of Toronto, Graduate Prosthodontic clinic to address compromised aesthetics and fit of a recently made ISC in site 12. The patient reported discomfort and tightness between the restoration and the mesial of the adjacent tooth 11, open distal contact with the adjacent tooth 13, and dissatisfaction with the appearance of the restoration (contour and shade) and of the adjacent interproximal soft tissues (black triangles at the gumline between the restoration and the adjacent teeth 13 and 11). (Fig. 1) A review of the patient’s records revealed that implant 12 was an internal connection design (Nobel Replace Conical Connection, narrow platform, 3.5 x 10 mm). Two previous attempts to restore the implant were not successful due to aesthetic and technical difficulties experienced by the previous treatment team, and hence the patient was referred to the Graduate Prosthodontics clinic.

Fig. 1A

Fig. 1B

Clinical assessment

Extra-oral assessment was unremarkable. Intra-oral examination revealed heavily restored dentition with multiple porcelain veneers, screw-retained implant-supported crowns, tooth-supported bridges, and direct composite resin restorations. Patient had medium smile line in the maxilla. Contact between ISC 12 and adjacent tooth 13 was open while the contact between ISC 12 and adjacent tooth 11 was very tight. Interdental papilla was absent between implant-supported crown 12 and adjacent teeth 13 and 11; blunted interdental papillae were present between other maxillary anterior teeth (11, 21, 22, and 23). Soft tissues in the maxilla appeared generally healthy except localized soft tissue inflammation around implant 12. ISCs 12 and 22 were not symmetrical, and long-axis of 12 was not in harmony with the adjacent or the contralateral teeth. No mobility or sensitivity to percussion was noted in the anterior maxilla. The partially edentulous mandible was restored with a removable partial denture. (Fig. 2)

Fig. 2

Radiographic assessment

Radiographic examination of implant 12 revealed an ISC (consisting of a titanium base and a zirconia crown) that was not seated completely due to possible binding of the ISC with crestal bone distal of tooth 11. (Fig. 3) No peri-implant radiolucency was present around implant 12; however, mild-to-moderate crestal bone loss or remodeling was apparent. Implant 12 appeared to be deeply positioned. Open margins of adjacent veneer restorations 11 and 21 were observed as incidental findings. The patient was informed about the incidental findings and encouraged to seek appropriate treatment.

Fig. 3

Exploratory assessment and definitive diagnosis

The basic treatment plan was formulated and consisted of three steps. First, we planned to access the ISC and assess its fit, shape and relationship with the adjacent soft and hard tissues. We were looking to develop a better understanding of the aetiology of the patient’s complaints and the previous teams’ treatment difficulties. This insight would then direct subsequent care. If the existing crown could not be made to seat fully while establishing proper interproximal contacts – and we felt that this is a distinct possibility – we planned to create a provisional ISC to optimize interproximal contacts, contour of restoration, aesthetics, and peri-implant soft tissues. Lastly, we planned to create a new definitive ISC.

The findings of initial assessment and the management plan were discussed with the patient, and informed consent was obtained.

Treatment

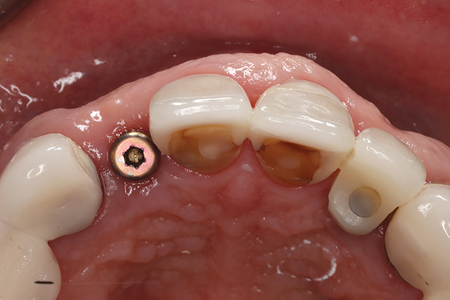

First, initial impressions were taken using alginate (Jeltrate, Dentsply Sirona, Ontario, Canada) to create diagnostic casts for further analysis. A diagnostic wax-up of tooth 12 was performed to evaluate optimal final aesthetic result. Removal of screw access filling of ISC 12 revealed that the abutment screw was loose. We removed the ISC 12 and noted significant soft tissue irritation and inflammation. (Fig. 4) We confirmed that the existing crown could not be made to seat fully on the implant. Due to the significant inflammation in the site, we felt that it is critical to allow inflammation to settle down first before attempting further care. Healing abutment (narrow platform 3.6 x 5 mm) was placed, and the patient encouraged to rinse the area with warm salt water.

Fig. 4

One month follow-up revealed healthy soft tissue with no inflammation. (Fig. 5) Further assessment was done to evaluate any bony interferences to the seating of the impression coping. Upon anesthetizing the patient, the narrowest bone mill drill (4.4. mm) and its guide (Nobel Biocare Canada Inc.) were used passively by hand (not in a handpiece) in a diagnostic manner to advance fully, and we confirmed that there was no bony interference up to 4.4 mm diameter. (Fig. 6) When attempting to seat the open tray impression coping, we noted that it contacted the adjacent tooth 11 in the coronal aspect due to the narrow mesiodistal space of 12 site and slight mesial positioning of the 12 implant. To overcome this problem, the impression coping was modified in the coronal aspect using high speed carbide bur (Brasseler, USA) to eliminate contact with the adjacent tooth and ensure passive seating. (Fig. 7) Complete seating of the modified impression coping was confirmed by a periapical radiograph. Following impression taking and preparing the master cast, a screw-retained provisional PMMA (Jet, Lang dental, Illinois, USA) ISC was made in accordance with the diagnostic wax-up. Provisional ISC was inserted and followed for one month. A re-evaluation after one month revealed the presence of healthy soft tissue and patient satisfaction with the appearance. (Fig. 8) The successful outcome of the provisional phase allowed for the execution of the final step of the treatment plan – fabrication of a new definitive ISC 12.

Fig. 5A

Fig. 5B

Fig. 5C

Fig. 6

Fig. 7A

Fig. 7B

Fig. 8A

Fig. 8B

The final impression for the definitive ISC was made using open tray impression technique with custom impression coping to transfer emergence profile developed with the provisional restoration to the master cast. (Fig. 9) Definitive screw-retained ISC was made of zirconia layered with feldspathic ceramic on the labial surface according to the provisional crown contour that was tested and approved by the clinician and the patient. The patient was pleased with the definitive restoration. (Fig. 10) Complete seating of the definitive restoration was confirmed with a periapical radiograph. (Fig. 11). Screw access channel was closed provisionally with PTFE (PTFE film tape, 3M) and clear polyvinyl siloxane (Exaclear, GC) material, and the patient was scheduled for a one-month follow-up re-assessment.

Fig. 9A

Fig. 9B

Fig. 10A

Fig. 10B

Fig. 10C

Fig. 10D

Fig. 11

Follow-up

The patient returned one month later for a follow-up re-assessment. The patient did not report any concerns. Clinical assessment revealed healthy soft tissues. Provisional filling was removed, and the crew access channel was closed with PTFE tape and A1 resin composite (3P ESPE). Optimum occlusion was confirmed. The patient was very pleased with the care received, and she was referred to the yearly maintenance program.

Discussion

This case report describes the management of prosthetic challenges of a single ISC in the anterior maxilla. The radiographic assessment revealed that the previously made ISC was not seated completely, and clinical examination demonstrated suboptimal prosthesis aesthetics.

Management of such cases begins with understanding the aetiology and establishing tissue health. We suspected that the original impression – and, hence, the master cast – may have been inaccurate due to binding of the impression coping on the adjacent tooth. This was compounded by the mesio-distal width of the restoration that was too wide for the narrow maxillary lateral site and may have bound on the surrounding bone. This would explain why the crown could not seat fully and why it had an open contact on one side and a contact that was too tight on the other. The co-occurrence of the two issues – inaccurate master cast and excessive restoration contours – may have complicated diagnosis. This case illustrates that when struggling to come up with an explanation for what is happening clinically, one needs to consider the possibility that more than one issue may be at hand.

In complex diagnostic situations related to implant-supported prostheses it is often helpful to take a step back, remove the prosthesis and re-insert the healing abutments. Once soft tissue health is established, delivery of a provisional restoration is critical to help come up with a diagnosis (if one has not already been found) and to test out a solution that resolves the patient’s complaints and promoted long-term aesthetics, function and health (Sadan et al., 2004).

In this case, the diagnostic and provisional phases paved the way for the definitive restoration to achieve optimal results. The modified implant impression coping facilitated seating and engagement in a narrow mesiodistal space, while the provisional restoration created an ideal emergence profile, ruled out the need to modify bony contours, and confirmed our ability to address the patient’s aesthetic concerns.

Conclusion

Treatment of the anterior maxilla with single implant-supported restoration is one of the most challenging solutions in implant dentistry, and an error in any treatment step can result in an aesthetic or technical failure. Complications with implant-supported restorations can be challenging to diagnose and treat when multiple issues are present. It can be helpful to take a step back, remove the prosthesis, re-establish tissue health, and fabricate a provisional restoration to test out resolution of the patient’s complaints and our ability to deliver a predictable definitive prosthodontic solution.

Oral Health welcomes this original article.

References

- Brägger U, Krenander P, Lang NP. Economic aspects of single-tooth replacement. Clin Oral Impl Res. 2005;16(3):335–41.

- Chang M, Odman P, Wensstrom J, Andersson B. Esthetic outcome of implant-supported single-tooth replacements assessed by the patient and by prosthodontists. Int J Prosthodont. 1999;12:335–41.

- Sadan A, Blatz MB, Salinas TJ, Block MS. Single-implant restorations: A contemporary approach for achieving a predictable outcome. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;62:73–81.

About the Authors

Dr. Majid Zakeri earned the DDS degree from Mashhad University of Medical Science, Iran. After practicing general dentistry in Iran and in Canada, he was accepted into the Graduate Prosthodontists Program at the University of Toronto where he is currently a 3rd year resident.

Dr. David Chvartszaid is an Assistant Professor at the University of Toronto and the chief-of-dentistry at Baycrest Hospital (Toronto). He is a specialist in Prosthodontics and Periodontics and holds master’s degrees in both from the University of Toronto. David Chvartszaid is a past director of the Graduate Prosthodontics program at the University of Toronto and is a past president of the Association of Prosthodontists of Canada.