Background and Context

Like many health fields, dentistry has been characterized throughout the years for innovating and improving upon existing interventions. Established and “classical” approaches, materials and techniques have often stood the test of time compared to more innovative and so-called “cutting-edge” technologies. In pediatric dentistry, this has proven to be true, especially when it comes to restoration materials and techniques. The stainless-steel crown (SSC) continues to be the gold standard in restoring primary molars.1,2 This is evidenced by years of research and scientific scrutiny, as well as clinical practitioner preference and usage, recently recompiled in the form of different systematic reviews and metanalyses.3,4 Amalgams, composite resins, and even the newer glass ionomer cement (GIC) materials have presented themselves as alternatives in replacing the SSC, but as the latest Cochrane review on the matter states from their conclusions (that): Teeth restored with preformed crowns are less likely to develop problems (e.g. abscess) or cause pain in the long term, compared to fillings.2 As it can be appreciated, the SSC proves to be a valuable material in the pediatric dental care armamentarium, and as it stands, its longevity and versatility have proven to be assets that still have realms to be explored.

The Hall Technique (HT) is a clear example of one of the ways that the SSC has evolved and proven that despite time and newer materials being available, it still has much to offer. Originally conceptualized from a need by Dr. Norma Hall, in her remote Scottish practice5, this technique has proven to be of great benefit from a behavioural, cost-effectiveness, and time-efficiency point of view. This use of the SSC has met a fair amount of resistance and pushback from critics, which is valid and necessary in order for the material to be safely used, adopted, accepted and implemented in the broader patient population. The increasing field of research around its applications, benefits and limitations continues to grow and through this scientific communication, the authors seek to shed some light on how the Hall Technique is a contemporary example in dentistry of how an old dog can be taught new tricks.

Use and indications

From its original description, the HT has had many explorations into its complete applications and limitations. Nevertheless, from its conception it was clear that its main benefit would be to diversify how the SSC is used, taking the known clinical effectiveness that this has, and combining it with a more patient and user-friendly approach. As the age of minimally invasive dentistry rolled along, pediatric practices demanded an approach to full-tooth coverage of considerably damaged molars, without the need for wearing sound tooth structure (many times needed to conventionally fit a SSC) and/or risking the damage of adjacent teeth.6,7 This necessity became ever more evident as the COVID-19 pandemic settled in, and aerosol-generating procedures became less desirable in the profession.8,9

When talking about the Hall Technique, it is useful to first remember the recommendations on the use of the SSC, according to the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry Pediatric Restorative Dentistry Guidelines10:

- Restoration of primary and permanent teeth with extensive caries*

- Cervical decalcification*

- Developmental defects (mainly enamel in the likes of hypoplasia, hypocalcification)*

- When failure of another available material is increased (in the cases of certain interproximal caries situations, patients with bruxism)*

- After pulp therapy has been carried out

- For restoring a primary tooth that is to be utilized as an abutment for a space maintainer*

- Immediate restoration of fractured teeth

- As a main restorative choice when treating high caries-risk children.*

Asterisk, are those cases where the HT is directly indicated and brings its most benefits. It could be argued that the technique could be utilized after pulp therapy and immediate restoration, but the broader consensus does not currently recommend this.

Clinical Technique

The clinical steps and technique are described as followed by Dr. Nicola Innes, and her working group (they have pioneered the study of the technique from its conception) from their different publications.11,12 Figure 1 is a graphic representation and a step-by-step of the clinical steps for the Hall Technique.

Fig. 1

a) Case Selection: As with any clinical decision, diagnosing and choosing the adequate treatment for patients is the key to success. The biological basis of utilizing the Hall Technique is grounded on the sealing of caries lesions and thus disrupting the dysbiotic nature of noxious bacteria to the dental tissues and structure. Once the tooth is sealed, the caries-inducing environment in the lesion will no longer be able to “interact” with unfavourable oral conditions. The nature of the SSC will permit complete coverage of the tooth, thus restoring lost contact and masticatory areas, as well as preventing the development of new lesions. For this to be adequately achieved, the carious primary molar must be asymptomatic, and the caries lesion must have extended to the dentine. Nevertheless, it is imperative that sufficient remaining tooth structure for the SSC to be fitted be present. Along with this, enough dentine must be present (a “dentine bridge” or a layer of 1/3 of dentine thickness), as this will allow for reparative dentine to be secreted once the tooth is sealed. As part of the case selection, a thorough previous clinical history and full oral examination must be conducted, as it is crucial to discard any pulpal comprise (irreversible pulpitis or further). This entails that teeth should not display any visible sign of infection (e.g., fistula) or have elicited any type of previous pain that might suggest an irreversible pulpal pathology.

b) Child, Parental and Clinical Preparation: Adequate patient preparation by means of adequate behaviour guidance technique is an important aspect of this technique. One of the key benefits of utilizing this technique is the lack of a need for syringe-deposited anesthesia. Having said this, there might still be a component of discomfort or force applied to the tissue, which needs to be explained to the pediatric patient prior to executing the technique. The Tell-show-do technique is an excellent way to approach this, describing to kids that they will receive “a helmet” or a “shiny covering” on their tooth and explaining that this might feel like a “tight hug” when it is put in place. Parents must also be aware that the lack of local anesthesia being utilized might provoke kids to point out that they feel the crown being on tight, and it is important they are assured that this is transitory and that kids will feel comfortable as time goes by. Along with this, it is important to point to parents that kids might “feel their bite different” due to the crown initially settling, but that this (the occlusion) should be resolved in a matter of weeks (concerns regarding occlusal changes will be addressed further on in this article).

Clinically, the instruments that are needed for the procedure are:

- A dental mirror

- A straight probe

- A toothbrush or bristle brush

- An excavator

- A cement-loading spatula

- Band forming pliers.

- An instrument to set the crown

(ie. A bite stick)

The materials needed for the procedures are:

- Glass Ionomer Cement

- Orthodontic Elastic Separators

- Cotton rolls/dental gauze

- Dental floss

Integrating both the psychological (child and parental preparation) and clinical (instruments and materials) components will give way for more optimized clinical procedures and should also increase the correct execution of the technique.

c) Morphology, contact areas and occlusal assessment: Another integral aspect of the technique is understanding the clinical circumstances that one is working with. The preformed nature of the SSC is what confers its easiness of use and facilitates adaptation. Nevertheless, one must consider that with the HT, as no tooth wear is necessary, one must be very mindful of the morphological, contact area and occlusal aspects of the tooth one is working with.

When faced with challenging crown morphologies, one can rely on band-forming pliers to reshape the crown and adapt it according to the mesiodistal or vestibulopalatal/lingual needs that might be required.

Regarding contact areas, it is important to note that intact marginal ridges are always going to facilitate crown adaption. Abnormal contact areas (let this be due to proximal tissue loss and subsequent proximal tooth migration, or simply abnormal tooth morphology) can also be challenging and one can rely on the previously mentioned band adapting pliers or work around this challenge with the different crown sizes. Fortunately, spaces between primary molars tend to be wide (for example between canines and 1st molars). Nevertheless, when this is not the case, one can utilize orthodontic elastic separators to widen the interproximal contact spaces. These separators can be placed 2-5 days before the crown fitting appointment, and when they are removed, a space will have formed that will allow for adequate crown placement (similar to when these are placed prior to the placement of an orthodontic band).

Finally, it is expected that the occlusal vertical dimension (OVD) be increased after the placement of the crown. This must be disclosed to both the parents and the children, as the bite will “feel different” after the placement and potentially a couple of days after cementation. “Pre-crown” occlusion should be re-established in a period of 4 weeks after placing this (see occlusion and masticatory concerns later in this article).

d) Sizing the SSC: Correct sizing is an intricate part of the HT. As it tends to be with the conventional technique, preoperative selection (i.e.: knowing more or less what crown size will be needed) will facilitate and optimize clinical operational times. When sizing the crown on the tooth, it is imperative that the airway be protected, and the child be seated in an upright position. For additional protection, a sticking plaster can be utilized to ensure the crown while fitting. When trying the crown on the tooth, it might not be necessary to completely put the crown in, as it might be challenging to pull it out back (and one must remember the child is not anesthetized!). When working with a second primary molar where the first permanent molar has not erupted yet, it is imperative to not select an oversized crown as this might be a reason for the first permanent molar to be impacted as it erupts.

The tooth should be cleaned with a toothbrush or bristle brush before placement, to ensure that there is no plaque remaining on both the tooth and the surrounding gingiva.

e) Filling the crown with Glass Ionomer Cement: Once the correct crown size has been chosen and all the preoperative steps followed, preparation for crown cementation can proceed. One must be generous with the amount of glass ionomer cement that is placed and strives to keep operative areas dry should be made (the crown should also be dried pre-placement).

f) Initial Crown fit and seating: This step is also referred to as “first seating”, as it is the first time that the crown really makes its way down in full coverage of the tooth. Initial setting should be ensured by the clinician (this can be done with finger pressure) and once it is ensured the crown is being seated in a correct manner, the kid can be asked to “bite down hard” or a bite stick can be used to continue with the setting. As part of the preparation for this phase, the kid must be reminded that they might feel a sour (lemon-like) taste, as overflowing glass ionomer cement can make its way to the tongue (especially in the mandibular placement) and it’s best that the kid is warned beforehand.

g) Further fit and seating: Once the crown is set on the tooth, “second/final seating” should follow. At this point, cement excess must be cleaned at a superficial level. Once the child has bitten down appropriately on the crown, they should continue biting for 2-3 minutes, and this can be held in place by either the clinician with their finger or a cotton roll.

h) Final cement clearance, final occlusal assessment, and patient discharge: Once the final seating stage is concluded, the final cement excess clearance can be done; this specifically alludes to the removal of interproximal cement excess (with tooth floss) that might have overflown into the area. A bit of cement clearing in the gingival sulcus (with a probe) could also be carried out, just to make sure this is also cleared from any remnants. Conventional SSC placement normally suggests that blanching on the gingiva should not appear, but in this technique, this is inevitable (as the crown would not have been cut) and should disappear gradually. Parents should once again be reminded that the child’s bite might feel “a bit off” due to the occlusal changes, and softer foods might be recommended in the following meals, but most children will adapt to this in a matter of days.

Main advantages of the technique

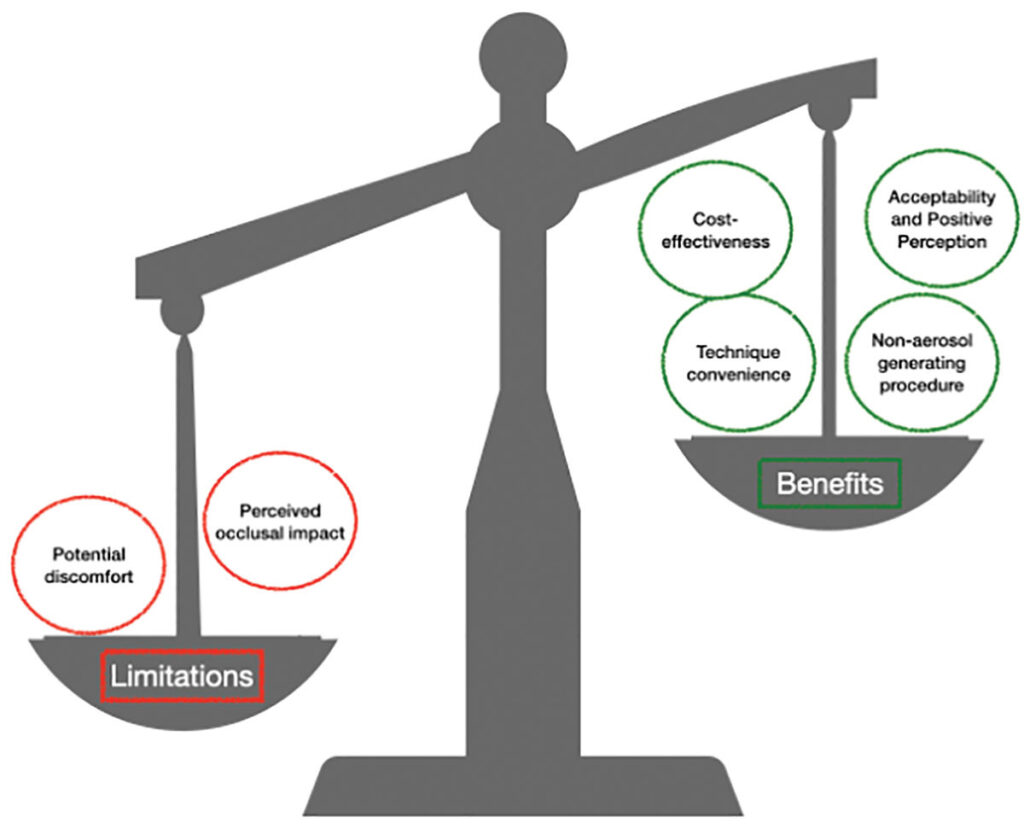

Taking all of these considerations into account, the place where the Hall Technique really shines in comparison to a “conventional” technique or placement of the SSC, has been explored in different capacities. Figure 2 represents a summary of both the advantages of the technique and its main limitations as identified by the authors.

Fig. 2

Convenience of the technique – As it has been pointed out, the fact that no local anesthesia, or tooth wear is required is what mainly makes this technique so attractive to use with pediatric patients. More specific uses and benefits have been explored in the literature, and more are sure to continue to accumulate as time goes by. Multiple trials have studied the techniques’ clinical effectiveness, where the benefits of the technique have been highlighted in specific contexts like: Australian Aboriginal populations when evaluated within a minimally invasive model of care,13 in patients with learning disabilities where positive clinical outcomes have been suggested.14 In terms of clinical survival, it has fared favourably when compared with the conventional atraumatic restorative technique,15-17 and the results from a noninferiority trial even suggested the technique reduces the need for general anesthesia.18 Nevertheless, it must be pointed out that some studies have suggested that the effectiveness of the HT is similar19 or inferior20 to the use of conventional restorative techniques. It is the authors’ opinion that the push for adopting more minimally invasive techniques like the HT will continue, as the benfits of the technique are quite clear.

Its advantage as a “non-aerosol generating” procedure – As one can observe from the technique description, minimal aerosol generation should be derived from the use of this technique. It has been pointed out that this is advantageous in situations like those presented by the COVID-19 pandemic, but one can look further and consider this is also advantageous when thinking in terms of community dentistry, or settings where full dental chairs and/or equipment might not be available.

Acceptability and Perception – An increasing (and important) body of work around the perception of dental treatments is allowing practitioners to understand the elements behind patient acceptance and compliance, and this is something that has also been explored within the HT. Araujo et al.15 studied both child and parental acceptability of the technique which was generally favourable in both groups (it must be pointed out that in this study parents reported that they preferred how glass ionomer cement looked when compared to the SSC used in the HT). Almaghrabi et al 21 found similar results, with a 96% favourability on parents’ behalf and operative-clinical times being an important variable for parents of children who underwent the technique. Nevertheless, it is interesting to mention that when looking at the dental professional perception of the technique Hussein et al.22 suggest that even though the technique might be popular and accepted among professionals in places like the UK, international dentists might be more skeptical about the use of the technique (from a cohort of over 700 pediatric dentists from 5 continents). Studying a similar phenomenon, Gonzalez et al.23 reported that dentists in the United States generally favoured the technique but that there tended to be more acceptability by people that practiced in rural locations and worked in community/public health settings. As evidence continues to accumulate regarding the acceptability and perception of the technique, barriers and challenges regarding its use will be better understood and strategies to better tailor the delivery of the technique can be designed.

Cost-effectiveness – An additional explored topic in the literature, and one that should increasingly be of interest to both private dental practices and the broader public health sector is that surrounding the economic aspects of executing the technique. A few studies that utilize rigorous economic evaluation methodologies have been undertaken and results suggest that the use of the HT is more cost-effective when evaluated in different scenarios. This cost-effectiveness has been observed when the HT is compared to conventional treatments (normally described as complete caries removal followed by a restoration)24–26, an immediate pulpotomy24, and treatment under general anesthesia.27 The results from these studies ultimately suggest that utilizing the HT approach is better in terms of the economic aspect and cost efficiency, though more studies with different perspectives (patient, healthcare system, society, etc.) are needed to fully champion the economic viability of this technique compared to other conventional treatments.

Limitations

Though the technique holds many elements that make it a clinical asset, it is also important to mention the limitations that the technique has and what the implications of these have been described as.

Potential Discomfort – The topic of potential discomfort children might experience when placing a crown with this technique (and mainly theorized around the lack of local anesthesia use) has sparked debate about how the technique fares in comparison to other approaches. Reports have shown that children report higher discomfort with the HT, compared to those who receive the atraumatic restorative technique (but cited that the discomfort probably was due to the orthodontic separator that is utilized, and the pressure perceived when placed)15. Boyd et al.28 reported that in their population, there was no significant difference in child-reported pain with the HT and the conventional technique, and the authors draw attention that this must not be normalized and better strives must be done on this front. Santamaria R et al 29 [echo these results where there was no significant difference in discomfort between the techniques they utilized (conventional restoration and non-restorative caries treatments). While, Ebrahimi et al.17 reported no discomfort on their patient’s behalf when comparing the HT to a modified ART and conventional SSC placement Patient perception and discomfort have been widely debated in the literature, and pain has been described as a subjective measure that varies from person to person; nevertheless, in children, this is something that must not be disregarded; as from a human rights perspective one must be cognizant of what one is making the child feel (no matter the way a child expresses), and one must also always think that less discomfort in dental treatment will most surely lead to better outcomes in behaviour compliance.

Occlusion and Masticatory Concerns – A due debate has arisen in the literature regarding the impact that the HT placement could have on the developing child’s occlusion. It has been described for many years that occlusal stability must be respected in order to maintain equilibrium between tooth structures, temporomandibular joints and masticatory muscles; yet the premise behind the HT would seem contradictory to this concept as the lack of crown occlusal reduction in the clinical procedure leads to the bite being altered once the crown is placed. This clinical change in occlusion has actually been cited as a possible deterrent to the use of the technique by US dentists.23 Clinically, studies like that of Nair et al 30 have closely studied bite force and occlusal vertical dimension and concluded that even though contact point change and masticatory forces are altered after placing the crown with the HT, this is regularized after 1 month of the placement, regaining what the authors cite as “occlusal equilibration”. Additional studies that have looked into the changes in the occlusal vertical dimension, come to the recurrent conclusion that this is regularized 4 weeks after the placement of the crown.15,17,31 When temporomandibular joint dysfunction has been studied, no clinical impacts have been observed in terms of associated signs and symptoms in children after utilizing the technique.31,32 A pilot study looking into the effects on masseter muscle activity after placement of crowns with the technique suggested that clenching in this muscle might be affected, but only temporarily.33 From patients’ perspectives, Almaghrabi et al.21 reported that 96% of children did not “complain about their bite” immediately after the treatment, but when studied prospectively, 56% did have some level of complaint/observation in change approximately a week after treatment. As it can be gathered from the scientific evidence that is currently available, the occlusal changes and accompanying impacts are apparent in the time after the placement of the crown, but clinical and patient perspectives do not seem to indicate that there are reasons to believe that children’s occlusion will be detrimentally affected by the use of the technique.

Conclusions

The Hall Technique is here to stay. As it tends to be with anything that brings forth change (especially to a solidified clinical approach), there must be a period of curiosity, research and adoption, that will meet various challenges along the way. It is important to understand that the Hall Technique will not be a solve-all response, but its value in the pediatric dental armament truly shines when the benefits of the technique are closely studied. As with similar clinical strategies (like the use of Silver Diamine Fluoride), a push to educate and create acknowledgement of the technique with both the patient and the clinician population must be pursued. As it tends to be with clinical techniques, there will be practitioners that will feel more akin to adopting the technique than others, as there will be patients that will also have a preference and this must be fully respected. Once again dentistry has proven to have the possibility of changing spectrums and possibilities and the Hall Technique can be included within this an excellent example of you can teach an old dog new tricks.

Oral Health welcomes this original article.

References

- Seale NS, Randall R. The use of stainless steel crowns: a systematic literature review. Pediatr Dent [Internet]. 2015;37(2):145-60. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25905656

- Innes NPT, Ricketts D, Chong LY, Keightley AJ, Lamont T, Santamaria RM. Preformed crowns for decayed primary molar teeth. Vol. 2015, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. John Wiley and Sons Ltd; 2015.

- Hu S, BaniHani A, Nevitt S, Maden M, Santamaria RM, Albadri S. Hall technique for primary teeth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Vol. 58, Japanese Dental Science Review. Elsevier Ltd; 2022. p. 286-97.

- Chua DR, Tan BL, Nazzal H, Srinivasan N, Duggal MS, Tong HJ. Outcomes of preformed metal crowns placed with the conventional and Hall techniques: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Vol. 33, International Journal of Paediatric Dentistry. John Wiley and Sons Inc; 2023. p. 141-57.

- Innes NPT, Stirrups DR, Evans DJP, Hall N, Leggate M. A novel technique using preformed metal crowns for managing carious primary molars in general practice – A retrospective analysis. Br Dent J. 2006 Apr 22;200(8):451-4.

- Innes NPT, Evans DJP, Bonifacio CC, Geneser M, Hesse D, Heimer M, et al. The Hall Technique 10 years on: Questions and answers. Br Dent J. 2017 Mar 24;222(6):478-83.

- Innes NP, Manton DJ. Minimum intervention children’s dentistry – The starting point for a lifetime of oral health. Br Dent J [Internet]. 2017;223(3):205–13. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2017.671

- Maru V. The ‘new normal’ in post–COVID-19 pediatric dental practice. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2021 Jul 1;31(4):528–38.

- BaniHani A, Gardener C, Raggio DP, Santamaría RM, Albadri S. Could COVID-19 change the way we manage caries in primary teeth? Current implications on Paediatric Dentistry. Vol. 30, International Journal of Paediatric Dentistry. Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2020. p. 523-5.

- American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Pediatric Restorative Dentistry. The Reference Manual of Pediatric Dentistry. 2022;401-14.

- Santamaría RM, Innes N. Sealing Carious Tissue in Primary Teeth Using Crowns: The Hall Technique. Monogr Oral Sci. 2018;27:113-23.

- Innes N, Evans D, Stewart M, Keightley A. The Hall Technique A minimal intervention, child centred approach to managing the carious primary molar: A Users Manual [Internet]. 2015. Available from: www.sign.ac.uk

- Arrow P, Piggott S, Carter S, McPhee R, Atkinson D, Mackean T, et al. Atraumatic Restorative Treatments in Australian Aboriginal Communities: A Cluster-randomized Trial. JDR Clin Trans Res. 2021 Oct 1;6(4):430-9.

- Robertson MD, Harris JC, Radford JR, Innes NPT. Clinical and patient-reported outcomes in children with learning disabilities treated using the Hall Technique: a cohort study. Br Dent J. 2020 Jan 1;228(2):93-7.

- Araujo MP, Innes NP, Bonifácio CC, Hesse D, Olegário IC, Mendes FM, et al. Atraumatic restorative treatment compared to the Hall Technique for occluso-proximal carious lesions in primary molars; 36-month follow-up of a randomised control trial in a school setting. BMC Oral Health. 2020 Dec 1;20(1).

- Boyd DH, Thomson WM, Leon de la Barra S, Fuge KN, van den Heever R, Butler BM, et al. A Primary Care Randomized Controlled Trial of Hall and Conventional Restorative Techniques. JDR Clin Trans Res. 2021 Apr 1;6(2):205-12.

- Ebrahimi M, Alireza •, Shirazi S, Afshari E. Success and Behavior During Atraumatic Restorative Treatment, the Hall Technique, and the Stainless Steel Crown Technique for Primary Molar Teeth. Pediatr Dent. 2020;187-92.

- Arrow P, Forrest H. Atraumatic restorative treatments reduce the need for dental general anaesthesia: a non-inferiority randomized, controlled trial. Aust Dent J. 2020 Jun 1;65(2):158-67.

- Maguire A, Clarkson JE, Douglas GV, Ryan V, Homer T, Marshman Z, et al. Best-practice prevention alone or with conventional or biological caries management for 3- to 7-year-olds: the FiCTION three-arm RCT. Health Technol Assess (Rockv). 2020 Jan;24(1):1-174.

- Santamaría RM, Innes NPT, Machiulskiene V, Schmoeckel J, Alkilzy M, Splieth CH. Alternative Caries Management Options for Primary Molars: 2.5-Year Outcomes of a Randomised Clinical Trial. Caries Res. 2017;51(6):605-14.

- Almaghrabi MA, Albadawi EA, Dahlan MA, Aljohani HR, Ahmed NM, Showlag RA. Exploring Parent’s Satisfaction and the Effectiveness of Preformed Metal Crowns Fitting by Hall Technique for Carious Primary Molars in Jeddah Region, Saudi Arabia: Findings of a Prospective Cohort Study. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2022;16:2497-507.

- Hussein I, Al Halabi M, Kowash M, Salami A, Ouatik N, Yang YM, et al. Use of the Hall technique by specialist paediatric dentists: a global perspective. Br Dent J. 2020 Jan 1;228(1):33-8.

- Gonzalez C, Hodgson B, Singh M, Okunseri C. Hall Technique: Knowledge and Attitudes of Pediatric Dentists in the United States. J Dent Child (Chic) [Internet]. 2021 May 15;88(2):86-93. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34321139

- Schwendicke F, Stolpe M, Innes N. Conventional treatment, Hall Technique or immediate pulpotomy for carious primary molars: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Int Endod J. 2016 Sep 1;49(9):817-26.

- Schwendicke F, Krois J, Robertson M, Splieth C, Santamaria R, Innes N. Cost-effectiveness of the Hall Technique in a Randomized Trial. J Dent Res. 2019 Jan 1;98(1):61-7.

- Banihani A, Deery C, Toumba J, Duggal M. Effectiveness, costs and patient acceptance of a conventional and a biological treatment approach for carious primary teeth in children. Caries Res. 2019 Jan 1;53(1):65-75.

- Tonmukayakul U, Forrest H, Arrow P. Cost-effectiveness analysis of atraumatic restorative treatment to manage early childhood caries: microsimulation modelling. Aust Dent J. 2021 Mar 1;66(S1):S63-70.

- Boyd DH, Foster Page LA, Moffat SM, Thomson WM. Time to complain about pain: Children’s self-reported procedural pain in a randomised control trial of Hall and conventional stainless steel crown techniques. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2023 Jul 1;33(4):382-93.

- Santamaria RM, Innes NPT, Machiulskiene V, Evans DJP, Alkilzy M, Splieth CH. Acceptability of different caries management methods for primary molars in a RCT. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2015 Jan 1;25(1):9-17.

- Nair K, Chikkanarasaiah N, Poovani S, Thumati P. Digital occlusal analysis of vertical dimension and maximum intercuspal position after placement of stainless steel crown using hall technique in children. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2020 Nov 1;30(6):805-15.

- Joseph RM, Rao AP, Srikant N, Karuna YM, Nayak AP. Evaluation of changes in the occlusion and occlusal vertical dimension in children following the placement of preformed metal crowns using the hall technique. Journal of Clinical Pediatric Dentistry. 2020;44(2):130-4.

- Kaya MS, Kınay Taran P, Bakkal M. Temporomandibular dysfunction assessment in children treated with the Hall Technique: A pilot study. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2020 Jul 1;30(4):429-35.

- Abu Serdaneh S, AlHalabi M, Kowash M, Macefield V, Khamis AH, Salami A, et al. Hall technique crowns and children’s masseter muscle activity: A surface electromyography pilot study. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2020 May 1;30(3):303-13.

About the Authors:

Dr. Fabio Arriola is a clinically trained pediatric dentist who is currently interested in understanding the missing links between pediatric preventive dentistry implementation and clinical efficacy maximization.

Dr. Kamila Sihuay-Torres is a dentist researcher currently pursuing a Ph.D. in Dental Public Health at the University of Toronto. She holds an undergraduate degree in dentistry and a Master’s in Public Health from the Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos (Peru). Her research focuses on conducting economic evaluations of oral health interventions for children using a Community-Based Participatory Research approach.

Emily R. Pynn is a 1st year medical student at Northern Ontario School of Medicine, previously completing a Bachelors of Science (Honours) at Queen’s University. Emily has been involved in research that explores the inequalities of underprivileged populations.

Dr. Herenia P. Lawrence is an Associate Professor in the Discipline of Dental Public Health in the Faculty of Dentistry at the University of Toronto. Her research explores population-based and preventive clinical and behavioural interventions that seek to improve the oral health of marginalized populations and reduce oral health inequalities in Canada.