The increasing incidence of oral potentially malignant disorders (OPMDs) requires vigilance on the part of dental practitioners in the identification of at-risk mucosal lesions and patients.1 OPMDs are defined as oral mucosal abnormalities that are associated with a statistically increased risk of developing oral cancer.2 The World Health Organization anticipates an increase in oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) associated with increased OPMDs.3 The most common OPMD is leukoplakia.4 Patients of older age and a history of significant alcohol and tobacco use were historically considered at highest risk for development of OSCC; however, OPMD may be identified in the absence of these prior recognized risk factors and in younger patients. While the incidence of OSCC associated with a precursor lesion is reported to be 6.26%, 49.3% of OSCC associated with previous OPMD are diagnosed at Stage I, resulting in improved outcomes with management of the disease.5

Lesions that are considered OPMDs have been identified by the World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Oral Cancer to include the following: leukoplakia, proliferative verrucous leukoplakia (PVL), erythroplakia, oral submucous fibrosis (OSF), oral lichen planus (OLP), oral lichenoid lesion (OLL), actinic keratosis (actinic cheilitis) (AK/AC), palatal lesions in reverse smokers, oral lupus erythematosus (OLE), dyskeratosis congenita (DC), and oral graft versus host disease (OGVHD).6 The potential for transformation of OPMD to OSCC must be considered when developing a follow-up strategy for patients who are diagnosed with lesions of concern.

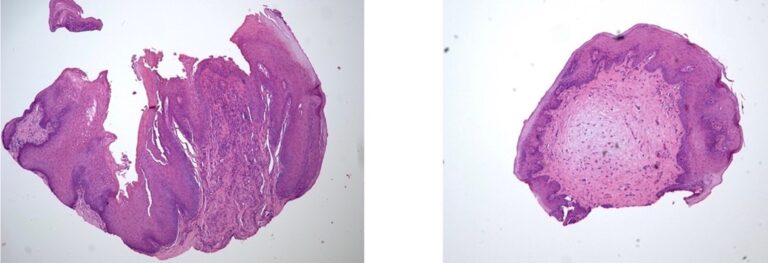

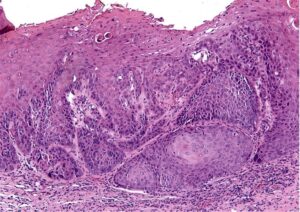

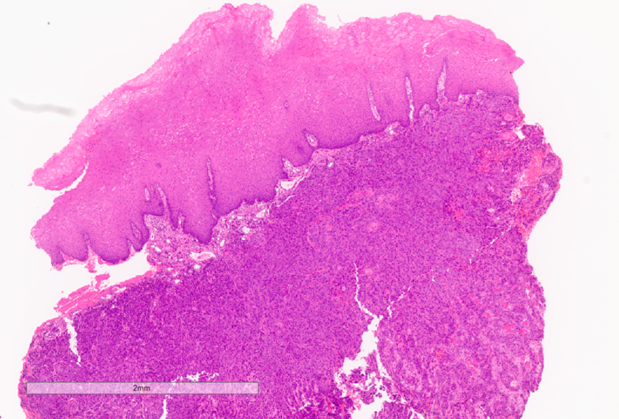

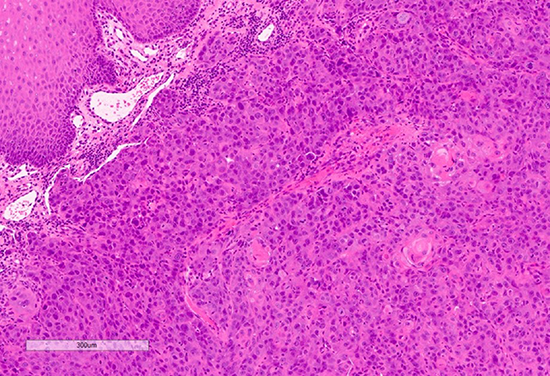

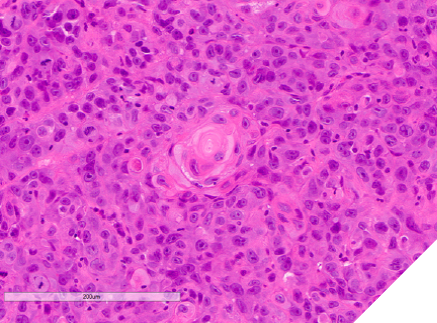

Globally, incidence rates of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) are increasing. Risk factors include tobacco, betel nut and alcohol abuse, medication reactions, HPV and Candida infection, and systemic conditions including immunosuppression, diabetes, and obesity.7 A systematic review of 69 studies, with 1,263,028 patients from 28 countries, found a mean prevalence of 1.36% (range 0.33-11.74%) with OPMD greater in males, and with tobacco and alcohol use.8 Malignant transformation of OPMD has been assessed in a systematic review from 2015-2020, which included 24 studies with 16,604 patients, and follow up of 7.67+5.02 years. The overall prevalence of oral leukoplakia was 4.1%, with malignant transformation from 1.1% to 40.8%, and a pooled risk of 9.8%.9 An earlier meta-analysis of 992 patients reported 12% progression in a median 4.3 years.10 A meta-analysis of 92 studies found an overall malignant transformation of 7.9% (CI 4.9-11.5%), and further examined risk in various OPMDs including: lichen planus 1.4%; oral lichenoid lesion: 3.8%; submucous fibrosis 5.2%; leukoplakia 9.5%; erythroplakia 33.1%; and proliferative verrucous leukoplakia 49.5%. The annual risk of transformation was reported as: lichen planus 0.28%; leukoplakia 0.57%; submucous fibrosis 0.98%; and PVL 9.3%.11 Malignant transformation of OLP and OLL may be higher than previously estimated. In a review of 33 studies including 12,838 lesions, 151 lesions progressed to SCC. Transformation appears to be increased in erosive/atrophic subtypes.12 Differentiation is needed between OLP and OLL as risk of progression to OSCC is higher in OLL. The proportion of oral lichen planus cases with malignant transformation may be higher than reported to date.13 In a retrospective study of 356 OLP patients, dysplastic changes were identified in 6.2%, and an additional 2.2 % developed dysplasia after 2 years of follow-up.14 Dysplastic change in lichenoid lesions is associated with increased risk of progression to SCC, reported as 6% compared with nondysplastic lichenoid lesions of <1.5%15 (Figs. 1-3).

Fig. 1

Fig. 2

Fig. 3

Case 1

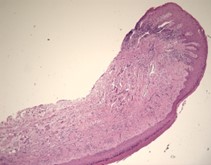

A 31-year-old male was referred for evaluation of a lesion of the anterior dorsal tongue. The patient was aware of the lesion for two years, and there was reported discomfort associated with the right latero-anterior aspect of the tongue. The medical history was non-contributory. A small elevated white lesion with a verrucous surface was visualized on the anterior dorsal tongue, with a second smaller white lesion to the left aspect of the larger lesion. The clinical appearance suggested a differential diagnosis of squa- mous papilloma. The lesions were excised and submitted for pathology. The diagnosis was mild to moderate epithelial dysplasia (Figs. 4 & 5).

Fig. 4

Fig. 5

Case 2

A 63-year-old female was referred for management of a white lesion of the attached gingiva. The lesion was noted during a dental recall appointment and was asymptomatic. The patient had no history of smoking or significant alcohol consumption. On clinical examination a 4 mm area of leukoplakia was observed on the facial gingiva between teeth 3.6 and 3.7. There was no associated erythema. Excisional biopsy was performed, with a differential diagnosis of hyperkeratosis and epithelial dysplasia. The pathology confirmed mild dysplasia (Figs. 6 & 7).

Fig. 6

Fig. 7

The patient was referred back 9 months later for evaluation of a new area of leukoplakia, presenting on the buccal gingiva between teeth 2.6 and 2.7 (Fig. 8). Excisional biopsy was again diagnostic for mild epithelial dysplasia. A long-term monitoring plan was established with the patient.

Fig. 8

Case 3

A 40-year-old male was referred with a six-week history of an ulcerated white lesion of the right lateral border of tongue. His history was positive for frequent aphthous lesions with a typical duration of 7-10 days. He did not recall noticeable tongue biting. The medical history was significant for gastroesophageal reflux disease treated with ranitidine, asthma, and anxiety not requiring medication. There was no history of smoking or significant alcohol consumption. On clinical examination there was no palpable lymphadenopathy. Diffuse leuko-erythroplakia was seen on the right lateral tongue border, with a central area of ulceration approximately 4 mm in diameter. The lesion was non-indurated on palpation. Incisional biopsy was performed. The patient was diagnosed with hyperkeratosis with high-grade dysplasia and superficially invasive squamous cell carcinoma. He was referred for prompt head and neck oncologic management. Staging confirmed early- stage disease with no lymphatic spread. Treatment consisted of right partial glossectomy. Neck dissection and chemoradiotherapy were not required (Figs. 9 & 10).

Fig. 9

Fig. 10

Case 4

A 64-year-old male was referred for evaluation of a lesion of the right lateral posterior tongue. His symptoms included severe pain and difficulty speaking. He reported symptoms for approximately 1.5 years, and recently had an adjacent tooth smoothed in an attempt to resolve the lesion. Medical history was significant for the loss of approximately 20% of his body weight. There was no history of smoking or significant alcohol consumption. Clinical examination revealed palpable lymph nodes in the right cervical chain that were non-tender to palpation. His speech was dysarthric. A large, indurated mass lesion was identified at the posterior aspect of the right lateral tongue, with allodynia on palpation (Figs. 11 & 12). Urgent incisional biopsy was scheduled under general anesthesia. A central area of necrosis was present. Biopsy was positive for invasive, moderately differentiated, keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma, conventional type.

Fig. 11

Fig. 12

The patient was referred for urgent head and neck work-up and staging. Metastatic tumours were identified in the lungs, and the patient was offered palliative therapy (Figs. 11 & 12).

Fig. 13

Fig. 14

Fig. 15

Discussion

Oral squamous cell carcinoma remains the most common malignancy in the oral cavity.16 The role of dentists in identifying abnormal tissue changes, and distinguishing potentially malignant changes from inflammatory changes, is essential for early diagnosis, allowing appropriate treatment and achieving optimal outcomes in oral cancer therapy. Dentists may identify early symptoms or signs of OPMDs and OSCC more commonly (72.5%) compared with physicians (40%).17 Clinical examination must include cranial nerve examination, head and neck cervical lymph node examination, and inspection and palpation of oral soft tissues. The etiology of OSCC, and oropharyngeal cancer (OPC), in particular, has been shown to have changed significantly, with diminished relationship to tobacco and alcohol use and an increase in disease related to human papilloma virus (HPV) infection. Opportunistic patient screening during both dental and medical examination, with a focus on high-risk populations (i.e., abuse of tobacco, betel nut, alcohol; history of HPV exposure, immunosuppression, or previous OSCC, OPC and OPMDs) is the recommended clinical standard.18

In addition to the shift in underlying disease etiology is an accompanying change in the prevalence of both OPMDs and OSCC, as well as the intraoral sites where lesions may be present. The incidence of SCC of the tongue in patients 40 years of age or younger exhibited a significant increase (4% to 18%) over a ten-year span.19 The risk factors associated with SCC in young adults are not defined. Amongst OPMDs, lesions of the lateral and ventral tongue exhibit the highest rate of progression to OSCC (11.4%), followed by floor of mouth (7.1%), and gingiva (6.5%), with these three sites accounting for 85.7% of cancers that develop from an OPMD.20 Potentially malignant lesions of the gingiva exhibit distinctive clinical features relative to other sites, including an increased female predilection, and generally present in older patients relative to other sites. Gingival involvement may mimic periodontal disease, making it essential for dentists to be aware of the potential of OPMDs to resemble inflammatory gingival and periodontal disease.21 As the frequency of malignant transformation of OPMDs of gingiva is similar to the floor of mouth, clinicians should be diligent in ensuring appropriate workup and diagnosis of these lesions.22

Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia (PVL) is an OPMD that exhibits a significantly greater potential for malignant transformation relative to other types of leukoplakia. These lesions may present on any mucosal surface, including gingiva, exhibit a female predilection, and do not exhibit a strong correlation with smoking history. These are persistent and progressive oral lesions that exhibit high rates of recurrence following excision, requiring early and aggressive management to optimize outcomes.23

Malignant transformation of a potentially premalignant lesion is multifactorial and, while the known risk factors of tobacco and alcohol use continue to predispose to malignancy, other factors including genetic, behavioral, underlying inflammation, microbial factors, systemic disorders, or medications may impact cellular metabolism and competency of immunosurveillance to an extent that the risk of malignant transformation is increased. Such patients may be considered as potentially premalignant as a whole, and require more intensive evaluation, follow-up, and management as indicated.24

Oral lichen planus and lichenoid reactions are being increasingly recognized, some of which are related to additional triggers of immune driven reactions documented following COVID-19 infection, COVID-19 vaccination, other vaccines such as herpes zoster, and other autoimmune reactions.25 Furthermore, medication triggered oral lichenoid lesions are increasing with increased polypharmacy, also impacting the increased incidence of mucosal changes.

Patients with early stage I and II OSCC exhibit high cure rates (90% two-year survival); however, stage III and IV cancers exhibit roughly half the survival rate even with multimodal therapy. This underscores the importance of appropriate screening and prompt biopsy of suspicious lesions. There are a number of adjuncts that may facilitate clinical recognition of tissue representative of OPMD or OSCC, including staining with toluidine blue, exfoliative brush cytology, and optical systems utilizing fluorescence technologies. While these methods provide a high degree of sensitivity, their specificity as diagnostic procedures are poorer; hence biopsy remains the gold standard for diagnosis. Delay in diagnosis and the resultant progression of disease are common allegations in malpractice cases related to head and neck cancer. It is therefore essential for health care providers to recognize abnormalities, obtain a definitive diagnosis or arrange prompt specialist referral to mitigate medicolegal risk.26

Conclusions

The increased prevalence of OPMDs and OSCC, as well as the changing trends in age of presentation and etiologic factors, require dentists to be vigilant in performing head and neck and oral soft tissue examination for screening of patients seeking routine dental care. Detailed evaluation, diagnosis, and follow-up of oral mucosal lesions is critical. Patients with OPMDs require ongoing follow-up due to the potential for malignant transformation, with heightened surveillance for patients with underlying systemic risk factors. Advances in adjuncts that facilitate clinical examination may facilitate early detection of progressing lesions, and advances in the management of OPMDs may reduce the risk of progression to OSCC. Early recognition with prompt diagnosis of OPMD lesions and those suspicious for OSCC is essential for optimizing treatment outcomes.

Oral Health welcomes this original article.

Acknowledgment: The authors would like to thank the Toronto Oral Pathology Service for the photomicrographs provided for this article.“

References

- Abadeh A., et al. Increase in detection of oral cancer and precursor lesions by dentists: Evidence from an oral and maxillofacial pathology service. JADA 150(6) June 2019

- Warnakulasuriya S. Clinical features and presentation of oral potentially malignant disorders. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod Volume 125, Number 6, June 2018

- Kumari P, Debta P, Dixit A. Oral potentially malignant disorders: etiology, pathogenesis and transformation into oral cancer. Front Pharmacol 2022;13:825266.

- Warnakulasuriya S, et. al. Nomenclature and classification of potentially malignant disorders of the oral mucosa. J Oral Pathol Med. 2007;36:575-580.

- McCord C. et. al. Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma Associated with Precursor Lesions. Cancer Prev Res 2021;14:873–84

- Warnakulasuriya S, Kujan O, Aguirre-Urizar JM, et al. Oral potentially malignant disorders: a consensus report from an international seminar on nomenclature and classification, convened by the WHO Collaborating Centre for Oral Cancer. Oral Dis. 2021;27:1862-1880

- Gormley M, Creaney G, Schache A, et al. Reviewing the epidemiology of head and neck cancer; definition, trends and risk factors. Br Dent J 2022;233(9):780-6.

- Zhang C, Li B, Zeng X, et al. The global prevalence of oral leukoplakia: a systematic review and metanalysis 1996-2022. BMC Oral Health 2023;23(1):645.

- Aguirre-Urizar JM, Lafuente-Ibanez de Mendoza, I, Warnakulasuriya S. Oral Dis 2021;28:1881-95). An earlier meta-analysis of 992 patients reported 12% progression in a median 4.3 years

- Mehanna HM, Rattay T, Smith J, McConkey CC. Head Neck 2009;31:1600-9.

- Iocca O, Sollecito TP, Alawi F, et al. Head Neck 2020;42(3):539-55).

- Offen E, Allison JR. What is the malignant transformation potential of oral lichen planus? Evid Based Dent 2022;23(1):36-7).

- Cheng LL. J Evid Based Dent Pract 2022;22(2):101717).

- Kakoei S, Torabi M, Rad M, et al. J Retrospective Study of Oral Lichen Planus and Oral Lichenoid Lesions: Clinical Profile and Malignant Transformation J Dent (Shiraz) 2022;23(4):452-8.

- Gonzalez-Moles M-A, Warnakulasuriya S, Gonzalez-Ruiz I, et al. Dysplasia in oral lichen planus: relevance, controversies and challenges. A position paper. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2021;26(4):e541-8).

- Neville, Damm et. al. Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology, 5th Edition. Elsevier, 2023

- Gellrich NC, Suarez-Cunqueiro MM, Bremerich A, Schramm A. Characteristics of oral cancer in a central European population: defining the dentist’s role. J Am Dent Assoc. 2003;134:307-314.

- Epstein JB, Huber MA. The benefit and risk of screening for oral potentially malignant epithelial lesions and squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod Vol. 120 No. 5 November 2015

- Myers JN et. al., Squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue in young adults: increasing incidence and factors that predict treatment outcomes. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2000; 122(1):44-51

- McCord C. et. al. Progression to malignancy in oral potentially malignant disorders: a retrospective study of 5,036 patients in Ontario, Canada. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2023;136:466_477

- Al-Sabbagh M, Hawasli A, Kudsi R, et al. Carcinoma mistaken for periodontal disease: The importance of careful consideration of the clinical and radiographic findings. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2021;113(5) e151-6.

- Cabay RJ, Morton TH, Epstein JB. Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia and its progression to oral carcinoma: a review of the literature. J Oral Pathol Med (2007) 36: 255–61

- Ilhana B, Epstein JB, Guneria P. Potentially premalignant disorder/lesion versus potentially premalignant patient: Relevance in clinical care. Oral Oncology 92 (2019) 57–58

- Güneri P.Epstein JB. Late stage diagnosis of oral cancer: Components and possible solutions. Oral Oncology 50 (2014) 1131–1136

- Alabdulaaly L, Sroussi HS, Epstein JB. New onset and exacerbation of oral lichenoid mucositis following SARS-CoV-2 infection or vaccination. Oral Diseases 2022;28(S2):25637.

- Epstein JB et. al. Head and neck, oral, and oropharyngeal cancer: a review of medicolegal cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2015;119:177-186)

About the Authors

Dr. Marshall Freilich is a board-certified Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeon and holds a Master of Science degree in Orofacial Pain and Oral Medicine. He is a staff surgeon at Humber River Hospital, and maintains a private practice in Toronto, Canada.

Dr. Joel Epstein is Director of Dental Oncology, City of Hope National Medical Center Durate, CA; and Professor, Dept. of Surgery, Cedars-Sinai Health System, Los Angeles, CA; and has an Oral Medicine practice in Vancouver, BC.