As anyone who has made any earnest foray into the delivery of cosmetic dental treatment has likely learned, there are some practitioners who are extremely talented and who are willing to share their expertise with those of us who wish to bring the best quality of care to our patients and communities. Those of us who practice in less rarified air would be foolish not to take advantage of the learning opportunities such gifted individuals offer our profession. Understanding the principles of smile design and case selection, the relative merits of various materials, how to make best use of various instruments and devices; these are among the skills that can be acquired or enhanced by availing ourselves of the lectures and hands-on training that are offered by those whose abilities qualify them to offer this kind of guidance. However, in 30 years of providing cosmetic dentistry in my community, I have discovered that for those of us not practicing in localities swarming with the rich and famous, it can be very useful to have certain adjuncts at our disposal that might be able to make treatment more accessible to a wider range of patients as well as enhancing the outcomes of our treatment. The purpose of this article is to discuss two such adjuncts.

A reasonable grasp of the concepts of smile design enables us to recognize the value of proper proportionality in individual teeth as well as relative to other nearby teeth in the smile. It is easy enough to recognize when a patient’s teeth appear too short relative to their length, for example. It is a mistake in such instances, in my opinion, to make assumptions about how to treat such a situation that might depend, say, on a low smile line. In my experience, people who are unhappy with the appearance of their teeth will often have learned not to reveal them any more than necessary when smiling. Once we make improvements to that appearance, even imperfect improvements, many patients will re-learn their smile and thereby expose the shortcomings of our work if we allow them to exist. For the purposes of this article it is not necessary to delve into the different causes for teeth appearing too short. We know that in many cases there exists adequate or nearly adequate length of anatomic crown even though the clinical crown may be highly inadequate. Additionally, we may also be called upon to find a restorative/cosmetic solution to teeth that have excess space between them. Teeth that must be widened may often also need to be lengthened to achieve proper proportionality. It is not difficult to make the argument that in such cases ideal treatment will spill over from purely restorative techniques and require alteration of soft and hard tissue that is not tooth structure. For most readers this is hardly revelatory. However, the question arises; how do we accomplish the alteration of these other tissues? Of course any good restorative or cosmetic dentist will have relationships in his or her professional communities with a surgeon or periodontist who can certainly perform the necessary clinical crown lengthening. Many of us who are not such specialists will feel comfortable doing some gingivectomy with a blade or diode laser or electrosurge. Some may even feel competent to lay a flap and reduce the bone level using a bur or other method. Most, however, are likely to refer out the cases where osseous reduction is required. This approach is completely legitimate, but does possess a few potential drawbacks. As soon as a cosmetic case leaves your office to have some portion of the treatment provided elsewhere, you have lost some control and are hoping that your specialist will fully grasp your needs and facilitate your smile design appropriately. Additionally, a certain percentage of patients will never follow through on any of the treatment because having to bring a specialist into the mix increases the complexity of the process as well as the intimidation factor. Beyond that, it also increases cost in most cases. I long ago became convinced that there were substantial advantages to being able to execute all aspects of such treatment myself. Pursuant to that I have found that the use of a hard-and-soft tissue laser has proven invaluable. My particular laser of choice has been the WaterlaseMD by BioLase, though there are other devices with similar capabilities. The case presented here is perhaps an extreme example of circumstances where said laser was indispensable, but serves as a useful demonstration of its virtues.

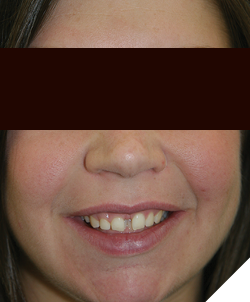

“Cara” presented in my Wilmington, DE, office with the chief complaint that her teeth were “too small” and there were large gaps between them. Figures 1-6 reveal why such concerns were well-founded. This appeared to be a case exhibiting a combination of tooth-width/arch-length discrepancy as well as altered passive eruption. It was clear that it was not going to be possible to address this patient’s aesthetic requirements without a combined restorative/periodontal approach. The patient was highly motivated to proceed but as a young person with the expenses of pending nuptials looming, she was interested in controlling costs as much as possible. As someone also trying to advance her career she wanted to minimize total numbers of visits and because of the planned wedding, wanted to keep the timeline on the treatment as short as possible while still achieving the desired results. All of this argued for keeping her treatment entirely “in-house.” A treatment plan involving clinical crown lengthening with osseous reduction/re-contouring was agreed upon.

Fig. 1

Fig. 2

Fig. 3

Fig. 4

Fig. 5

Fig. 6

The crown lengthening was accomplished in a single visit but in two stages, which is typical when performing this “closed flap” technique. Figures 7-9 show stage 1 wherein the gingival heights of contour are established and the full anatomic crown is exposed. This stage is generally nearly bloodless. In the second stage, the laser tip is laid parallel to the long axis of the tooth and simultaneously fired and inserted below the gingival margin to ablate bone and reduce the osseous level and thereby re-establish proper biologic width. This is a “touch technique” which does not allow for visualization of the bone but is accomplished by tactile feedback. A perio probe is used throughout to determine that enough bone has been reduced. Figures 10-12 demonstrate the appearance immediately following Stage 2. At this stage there is typically more blood since small marrow spaces are being opened. Nevertheless, healing is usually rapid and post-operative pain is reportedly very manageable with minimal amounts of OTC analgesics. Healing is also highly predictable with very little shrinkage or rebound of the gingiva. It is often possible to proceed to the restorative aspect of a case in as little as two weeks with confidence in the stability of the soft tissue. However, in this case because the tissue re-contouring was so extensive, we waited 2 months to proceed. Figures 13-15 reveal the condition and position of the soft tissue immediately prior to veneer preparation.

Fig. 7

Fig. 8

Fig. 9

Fig. 10

Fig. 11

Fig. 12

Fig. 13

Fig. 14

Fig. 15

From this point on the case was completed with eight lab-made porcelain veneers. Figures 16-21 show the completed case approximately two weeks post-insertion. A small “black triangle” is notable between #s 8 and 9, but given that the most apical aspect of the contact areas is 5mm from the osseous crest, with adequate time and tissue maturity, it was expected that the papilla would fully form in this area. Pt. moved away from Wilmington and contact was lost, so confirmation of this has not been possible.

Fig. 16

Fig. 17

Fig. 18

Fig. 19

Fig. 20

Fig. 21

The second case pictured here, “Danielle,” presented in the office with a chief aesthetic complaint of teeth that were too small and had irregular gaps between them. Arch form was overall good, as was oral hygiene. This appeared to be primarily a case of tooth-width/arch-length discrepancy. Figures 22-28 clearly reveal the reasons for her complaint. The patient was a single parent who had recently begun her career as a school teacher. Though she had saved specifically for the purpose of being able to afford this treatment, she was still interested in controlling costs as much as possible. Given the fact that the spacing issue was present anteriorly in both arches, veneering multiple teeth in both arches was unavoidable. In the maxillary arch there seemed little choice but to go with lab-made porcelain veneers in order to have maximum control over shade, contour and characterization of the teeth. In the mandibular arch, however, it was determined that satisfactory aesthetic results could be achieved by fabricating the necessary veneers in-house using the Cerec system. By cutting the number of restorations that were made by the lab nearly in half, substantial savings were realized. A treatment plan for eight lab-made porcelain veneers for the maxillary arch and six CAD/CAM-produced veneers for the mandibular arch was agreed upon.

Fig. 22

Fig. 23

Fig. 24

Fig. 25

Fig. 26

Fig. 27

Fig. 28

At the time that this case was performed, the best choice of material for the in-house mandibular veneers was Empress II. A wax-up had been generated for analysis of the case and was used as a template for the permanent veneers during the CAD process. The Cerec software allows for a duplication feature which is highly advantageous in a situation like this. Other CAD/CAM systems have similar features. The ability to prepare, fabricate and deliver the mandibular restorations first, and in the same visit also facilitated preparation and provisionalization of the maxillary teeth. As in the first case shown, some laser re-contouring of the soft and osseous tissues was necessary in order to achieve good proportionality and emergence profile while widening teeth. In this case the use of this technique was able to be kept much more limited.

Once the final maxillary restorations were delivered, it seemed clear that very little, if any, aesthetic compromise resulted from the use of a milled, monolithic material for the mandibular restorations. Figures 29-35 show the completed case several weeks post-insertion. Unfortunately the patient suffered a blow to the mouth while participating in a “tough mudder” charity run resulting in fracture of a lateral veneer. Due to the loss of tooth structure, it became necessary to restore this tooth with a lab-made crown. Subsequent to that, the case has proven durable, as Figures 36-40 demonstrate. These images were taken recently, 12 years after the case was delivered. The patient remains very pleased with the results to this day.

Fig. 29

Fig. 30

Fig. 31

Fig. 32

Fig. 33

Fig. 34

Fig. 35

Fig. 36

Fig. 37

Fig. 38

Fig. 39

Fig. 40

While we all appreciate the virtues of “no-prep” or minimally invasive cosmetic dentistry, our patients will not always do us the favor of bringing ideal cases to us. We all also recognize the importance of having our patients receive appropriate orthodontic care or even periodontal therapy prior to engaging in final smile design for cosmetic cases. However, as the two cases presented here demonstrate, there are times when healthy mouths with reasonably well-aligned teeth will still not prove suitable for treatment with veneers only. It hardly needs to be pointed out that patients come in many sizes and shapes, as do their teeth. It helps to keep in mind that patients’ expectations for cosmetic dentistry do not limit themselves to the final aesthetic result. Time constraints, anxieties, misconceptions and financial constraints also play a significant role. Having a couple of “tools in the box” like those shown here can sometimes go a long way towards not only meeting, but exceeding your patients’ expectations. Devices such as those shown here require significant investments of time and money to acquire not only the hardware, but the competency to utilize them properly. However, if you have a commitment to increasing your cosmetic profile, delivering not only more but better treatment, such investments can yield significant returns for you, your practice and your patients.

Oral Health welcomes this original article.

About the author

Dr. Fay graduated from the University of Pennsylvania School of Dental Medicine in 1987. He did a 1-year general practice residency at the Medical Center of Delaware prior to beginning his career in private practice as an associate dentist in northern Delaware. He also held positions as a clinical instructor in the dental hygiene program at Delaware Technical and Community College and as clinical dentist/Dental Director in the Delaware correctional system. He transitioned into practice ownership in 1994 and now owns and operates five separate offices in northern Delaware and southeast Pennsylvania. He continues to practice today and has maintained a focus on cosmetic dentistry, laser dentistry and sedation dentistry for many years.